Current pre-hospital traumatic brain injury management in China

Kou Kou, Xiang-yu Hou, Jian-dong Sun, Kevin Chu

1School of Public Health and Social Work & Institute Health and Biomedical Innovation, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD 4059, Australia

2Royal Brisbane and Women's Hospital Metro North Hospital and Health Service, Butterfield Street Herston QLD 4029, Australia

Corresponding Author:Xiang-Yu Hou, Email: x.hou@qut.edu.au

Current pre-hospital traumatic brain injury management in China

Kou Kou1, Xiang-yu Hou1, Jian-dong Sun1, Kevin Chu2

1School of Public Health and Social Work & Institute Health and Biomedical Innovation, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD 4059, Australia

2Royal Brisbane and Women's Hospital Metro North Hospital and Health Service, Butterfield Street Herston QLD 4029, Australia

Corresponding Author:Xiang-Yu Hou, Email: x.hou@qut.edu.au

BACKGROUND:Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is associated with most trauma-related deaths. Secondary brain injury is the leading cause of in-hospital deaths after traumatic brain injury. By early prevention and slowing of the initial pathophysiological mechanism of secondary brain injury, prehospital service can signi fi cantly reduce case-fatality rates of TBI. In China, the incidence of TBI is increasing and the proportion of severe TBI is much higher than that in other countries. The objective of this paper is to review the pre-hospital management of TBI in China.

DATA SOURCES:A literature search was conducted in January 2014 using the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI). Articles on the assessment and treatment of TBI in pre-hospital settings practiced by Chinese doctors were identified. The information on the assessment and treatment of hypoxemia, hypotension, and brain herniation was extracted from the identi fi ed articles.

RESULTS:Of the 471 articles identified, 65 met the selection criteria. The existing literature indicated that current practices of pre-hospital TBI management in China were sub-optimal and varied considerably across different regions.

CONCLUSION:Since pre-hospital care is the weakest part of Chinese emergency care, appropriate training programs on pre-hospital TBI management are urgently needed in China.

Traumatic brain injury; Pre-hospital; China; Emergency medicine

INTRODUCTION

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a major health and socioeconomic issue around the world. It is the leading cause of trauma-related deaths and the most common cause of mortality and disability among the young people.[1]Globally, the incidence of TBI is rising rapidly because of the increasing use of motor vehicles in lowincome and middle-income countries.[2]

In China, the incidence of TBI ranged from 55.4 to 64.1 per 100 000 population in 1986.[3]Because of a lack of coherent systems for national registration of TBI, the incidence transition of TBI in the past decades is unknown.[4]However, the dramatic increase in the number of vehicles and high-rise buildings in China has increased the risk of both traffic accidents and high-level falls.[5]The number of people who died from road traffic accidents increased from about 60 000 in 1995 to 100 000 in 2003. Among these cases, brain injuries accounted for 38.7% to 57.3% of the deaths.[4]The population most affected by TBI death and disability was young men,[4]which are costly to society because of the years of potential lives lost and the working years of potential lives lost. Moreover, the proportion of severe TBI in China is much higher than that in other countries (20% vs. 10%).[4,6]This group of patients has the longest hospital stay and the highest hospital cost, and it has a high case-fatality rate.[7]To fi nd the reasons behind thehigh proportion of severe TBI in China may shed new lights on future TBI management and prevention.

Secondary brain injury, which occurs in minutes to days following primary injury, is the main cause of TBI mortality.[8]Post-injury events such as hypoxemia, hypotension, and intracranial hypertension can initiate the pathophysiological mechanisms of secondary brain injury.[9]A study[10]has revealed that there is a high incidence of these post-injury events at the occurrence of accidents. Accordingly, early prevention, identification, and correction of these events in the pre-hospital setting can lower the risk of secondary brain injury and reduce the case-fatality rate of TBI.[2]As such, many countries have established guidelines for TBI pre-hospital management over the past 15 years.[11–15]

Since pre-hospital care is the weakest part of Chinese emergency care,[16]suboptimal practices in TBI management may exist in pre-hospital settings. In this article, we reviewed the current practices of pre-hospital TBI management in China, while describing the current situation and analyzing the existing problem of prehospital TBI management in China.

METHODS

Chinese language research papers about pre-hospital TBI management in China published from 1 January 1998 to 31 December 2013 were retrieved using the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), which is the largest comprehensive Chinese-based information database. The types of resources in CNKI include journal articles, newspaper articles, theses, conference papers, and books.[17]All the research papers with the Chinese characters "颅脑外伤(head injury)", "颅脑创伤(head trauma)", "颅脑损伤(head damage)", "脑外伤(brain injury)", "脑创伤(brain trauma)", "脑损伤(brain damage)", and "院前急救(pre-hospital emergency treatment)" in the titles or as key words were included in the initial search.

TBI is defined as an alteration in brain function, or other evidence of brain pathology, caused by an external force.[18]Therefore, any cerebral condition caused by nontrauma mechanisms is not considered as TBI. Since there are no paramedics in China, the staff members in the prehospital care system are doctors, nurses, patient-carriers, and drivers.[16]Of this group, doctors play a crucial role in the pre-hospital management.[19]Therefore, the criteria for the literature search included articles concerning (i) brain injury conditions caused by trauma, (ii) emergency care in the pre-hospital settings, and (iii) assessment and treatment practised by pre-hospital doctors. Articles about pediatric patients or practices of nursing care were excluded. The references of the identi fi ed articles were examined to make sure that all relevant articles were included.

The information about the assessment of oxygenation, blood pressure, and clinical signs of brain herniation in addition to the treatment of hypoxemia, hypotension, and brain herniation was extracted from the identi fi ed articles. The information about the key practices of pre-hospital TBI management is discussed in the Guidelines for Prehospital Management of Traumatic Brain Injury, Second Edition (Brain Trauma Foundation, BTF).[12]

RESULTS

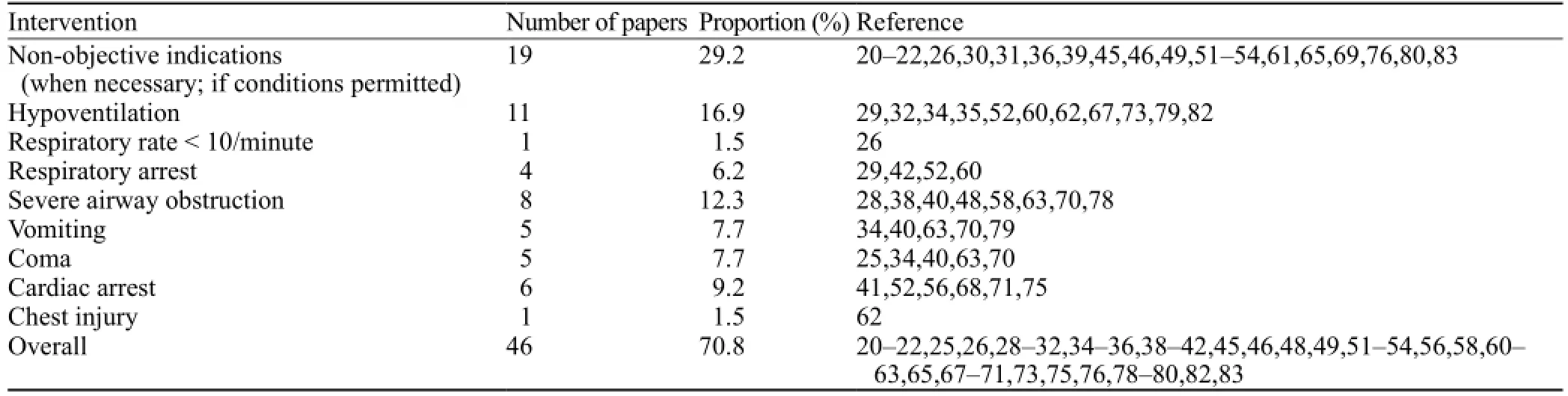

The initial search identified 471 articles. According to the selection criteria, 65 articles were included in the review at last (Figure 1). All the identified articles were peer-reviewed. Thirty-nine were original research articles, and the remaining articles were correspondence pieces without abstracts. Among these 65 research papers, 44 were cross-sectional studies reporting local practices of TBI management in pre-hospital settings. Twenty-one articles were case-control studies attempting to assess the important role of pre-hospital care in TBI management. In our review, 17 of the identi fi ed research papers discussed the management of all TBI patients and 48 concentrated only on severe TBI patients. An increasing trend in a number of reports during the time period reflects an increasing recognition of this problem (Figure 2).

Assessment of oxygenation and treatment for hypoxemia

Figure 1. Flow chart of the literature screening process.

In the 65 articles, 39 (60%) reported that the pre-hospital doctors assessed oxygenation for TBI patients in pre-hospital settings. Thirty-four (52%) assessed oxygenation by observing patients' breathing, whereas only 9 (14%) articles documented the measurement of patients' blood oxygen saturation.

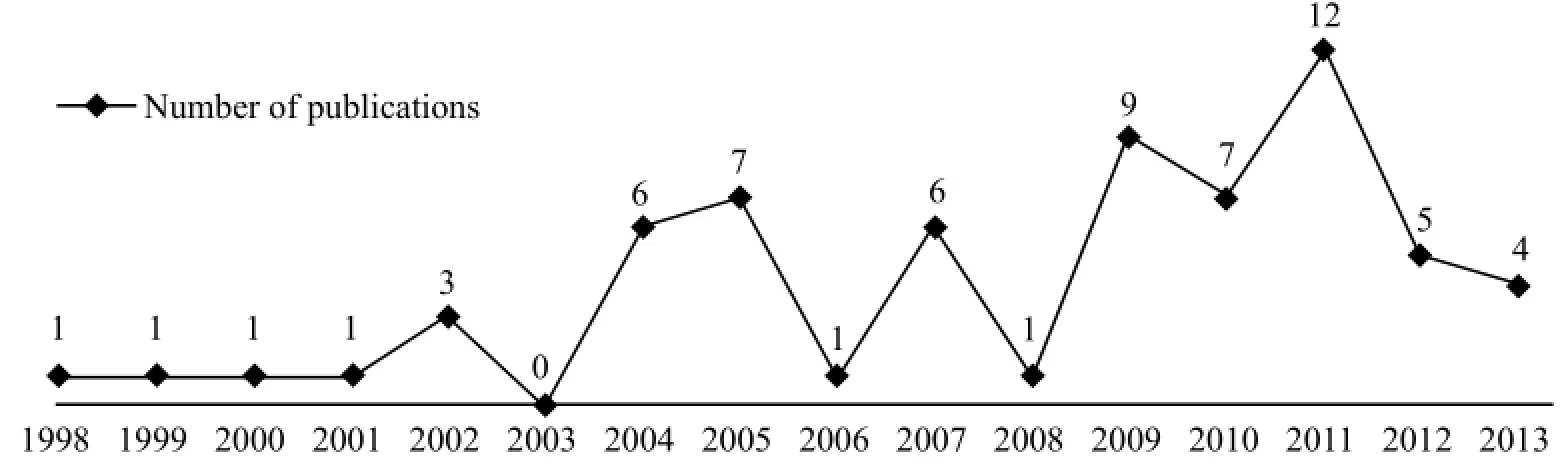

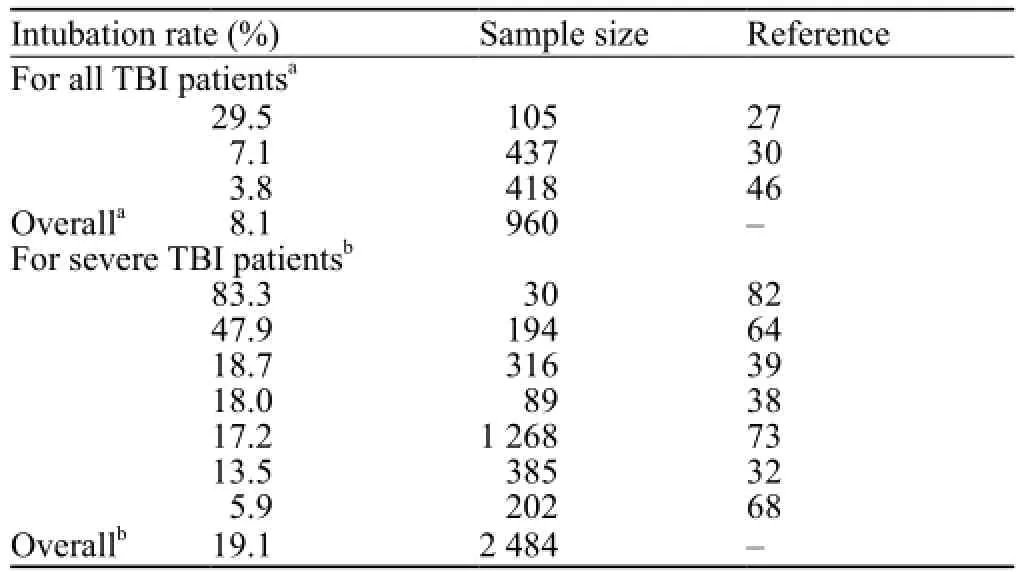

Almost all papers reported the pre-hospital doctors implemented airway management for TBI patients. In China, the most prevalent basic airway management was manual clearing, which was reported in 57 (88%) articles (Table 1). These practices included manual removal of vomit and regurgitation from the patient's oral cavity, nasal cavity, and pharynx. Even though 54 (83%) articles mentioned endotracheal intubation, only half of them stated clearly under what circumstance they intubated their patients, with indications varying in different regions (Table 2). Nineteen of the remaining articles described the intubation indicationas "intubate TBI patients when necessary". The remaining 8 articles mentioned intubation only, but did not give any indications. As a result, the intubation rate in China varied considerably (3.8%–83.3%) across regions (Table 3).

Figure 2. Number of publications in different years.

Table 1. Assessment of oxygenation and treatment for hypoxemia for TBI patients in Chinese pre-hospital settings

Table 2. Intubation indications for TBI patients in Chinese pre-hospital settings

Table 3. Intubation rate in TBI patients in Chinese pre-hospital settings

Twenty-two (34%) articles reported that the prehospital doctors implemented artificial ventilation for TBI patients, and that most of them used bag valve mask devices. None of the identified papers claimed that the doctors had monitored end tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO2) levels during ventilation. Eleven (17%) research papers documented the use of respiratory stimulants for TBI patients in pre-hospital settings (Table 1).

Assessment of blood pressure and treatment for hypotension

Assessment of TBI patients' blood pressure in prehospital settings was reported in 36 (55%) identified papers. Almost all papers stressed the correction of hypotension. The most common interventions reported were hemostasis (mostly through applying direct pressure) (83%) and fluid resuscitation (63%) (Table 4). Twentyseven (42%) identified papers documented the type of resuscitation fl uid used for TBI patients. The resuscitationfl uid used for TBI patients varied in Chinese pre-hospital settings. Among them, dextran (23%) and balanced salt solution (22%) were most prevalent (Table 4).

Table 4. Assessment and treatment for hypotension for TBI patients in Chinese pre-hospital settings

Table 5. Intracranial pressure management for TBI patients in Chinese pre-hospital settings

Table 6. Other interventions for TBI patients in Chinese pre-hospital settings

Table 7. Case-fatality rate of TBI during pre-hospital phases in China

Assessment of neurologic status and

treatment for brain herniation

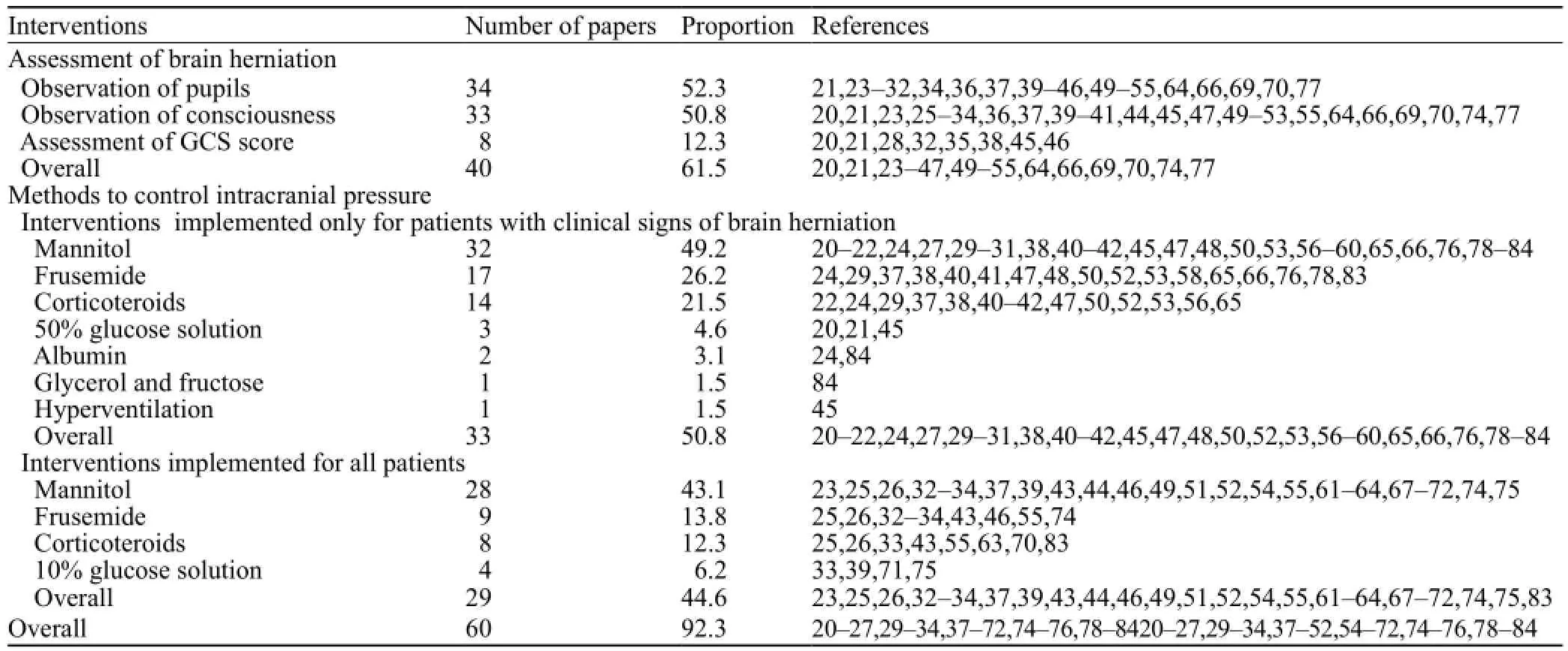

Forty (62%) papers claimed that their pre-hospital doctors assessed TBI patients' neurologic status in prehospital settings. Most of the papers showed clinical signs of brain herniation by observing the patients' pupils and levels of consciousness, but only 8 (12%) papers documented the measurement of the patients' GCS scores.

Interventions to control elevated intracranial pressure (ICP) were documented by 60 (92%) identified papers. Twenty-nine (45%) papers documented that agents had been administered to control ICP for all TBI patients without providing evidence that they had checked for the clinical signs of brain herniation in advance. The most common medications used to control ICP in Chinese pre-hospital settings were mannitol, furosemide, and corticosteroids (Table 5).

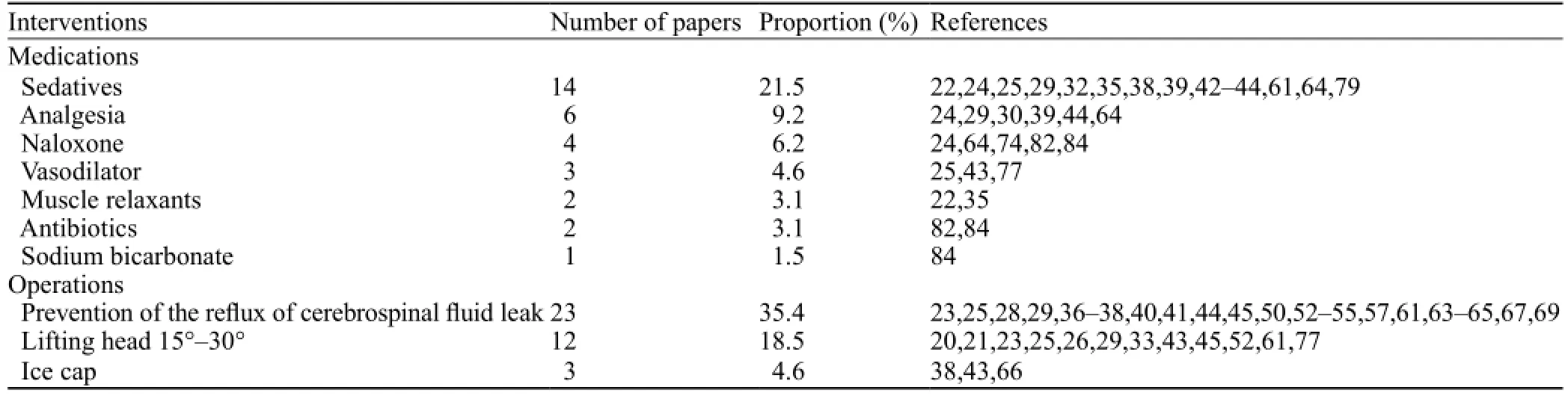

Other interventions

Other interventions discussed by the identified papers included some medications and operations (Table 6). Most research papers stated that they prevented intracranial infection in patients with open skull fractures by preventing reflux of cerebrospinal fluid leaks and administering antibiotics. The reflux of cerebrospinal fluid leaks was prevented by raising patients' heads for those with cerebrospinal rhinorrhoea, or by turning patients' heads to the leaking side for those with cerebrospinal otorrhea.

The proportion of TBI patients who died during the pre-hospital phases varied in the research papers. For all TBI patients, the overall case-fatality rate of TBI during pre-hospital phases was 4.48%, and ranged from 0% to 10.8% in different areas. For severe TBI patients, the overall rate was 10.4%, and rates ranged from 2.1% to 24.2% (Table 7).

DISCUSSION

Existing evidence has shown that China has a higher proportion of severe TBI compared to other countries, suggesting that the country could have suboptimal management of TBI in pre-hospital settings.This literature review presented the current situation of pre-hospital management of TBI in China, including problems in the management of oxygenation, blood pressure, and ICP in TBI patients.

Oxygenation, airways, and ventilation

Hypoxemia is independently associated with signi fi cant increases in morbidity and mortality in cases of severe TBI.[85]Evidence-based guidelines published by BTF suggested the continuous measurement of oxygen saturation in pre-hospital settings.[12]However, only 9 papers documented the measurement of oxygen saturation for TBI patients (Table 2). As a result, hypoxemia cannot be promptly identified and the ef fi ciency of airway management cannot be evaluated in many Chinese pre-hospital settings.

Many papers provided options for airway management (Table 2). Among them, practices such as turning the patient's head to one side if the patients were vomiting and pulling out the patient's tongue with tongue forceps were prevalent in Chinese pre-hospital settings. However, these practices were not commonly mentioned in the literature from other countries. In addition, most of the reviewed papers did not offer clear and appropriate indications for their airway management practices. For example, only 27 identified papers provided detailed objective indications for TBI intubation, and most of which were not aggressive enough when compared with the guidelines.[14]As a result, the overall intubation rate among severe TBI patients in China was 19.1%, which was far less than that of the US (43.0%).[86]Unclear and improper indications may lead to suboptimal practice in pre-hospital settings. According to one study in Hebei Province, China, 87 (51.6%) of severe TBI patients were suffering from airway obstruction on arrival, and 69.0% of them could not get enough oxygen because of airway obstruction or inadequate pre-hospital oxygen supplements.

Some researchers pointed out that failed or inappropriate intubation without the use of sedatives and muscle relaxants during intubation may worsen TBI outcomes.[88,89]Therefore, rapid sequence intubation (RSI), which is defined as an administration of an induction agent followed by neuromuscular blocking agents (NMBA) to induce unconsciousness and motor paralysis for tracheal intubation,[90]is recommended for pre-hospital TBI management.[11,12]However, none of these 65 research papers mentioned administration of NMBAs during intubation.

Suboptimal ventilation, especially hypocapnia caused by hyperventilation, is common in pre-hospital settings.[91]Intubated TBI patients who present with severe hyperventilation have significantly higher mortality rates than those without hyperventilation.[92]Therefore, monitoring ETCO2continuously to avoid suboptimal ventilation during pre-hospital phases is recommended.[12,14]Only 22 (34%) papers reported ventilation for TBI patients and none of them monitored ETCO2in pre-hospital settings (Table 2). Only one article stated in the discussion section that routine hyperventilation should be avoided in TBI patients.[35]

Hypotension and fl uid resuscitation

Patients with hypotension not corrected in the fi eld had a worse outcome than those whose hypotension was corrected by the time of arrival at the emergency department.[85]BTF suggests that patients with suspected TBI should be monitored in pre-hospital settings for hypotension.[12]However, less than half of the Chinese papers documented the measurement of blood pressure for TBI patients in pre-hospital settings (Table 5).

For the treatment of hypotension, BTF suggests that every hypotensive patient should be treated with isotonic fluids.[12]Current reviews suggested that only 60% of the identified papers reported they had used resuscitation fluid for their TBI patients. Among those papers which did not document the use of resuscitation fluid, 46% (11 of 24 papers) said they administered mannitol or furosemide to their TBI patients.[25,32,34,39,43,46,49,54,70–72]This situation may indicate a trend of overtreatment of brain herniation, and in turn, the ignorance of the adverse effect of hypotension on TBI patients in some Chinese pre-hospital settings.

Evidence showed that hypertonic saline is more effective in correcting hypovolemia when compared with hypertonic saline/dextran (HSD) and Ringer's lactate.[93]Moreover, hypertonic saline can also decrease ICP in TBI patients.[94]Hypertonic saline (7.5%) resuscitation is recommended by the guidelines.[11,12]In China, the use of hypertonic saline is not widespread. Only 8 (12%) papers reported the use of hypertonic saline in pre-hospital settings (Table 6).

Brain herniation

Since brain herniation can dramatically elevate the mortality in TBI, patients' clinical signs of brain herniation should be assessed frequently in pre-hospital phases.[12]In particular, the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS)is a significant and reliable indicator of the severity of TBI, and it can help to identify improvement or deterioration in neurological status through repeated measurements.[12]Even though 40 (62%) Chinese papers stated that they assessed the signs of brain herniation for TBI patients, only 8 (12%) documented the measurement of GCS scores for TBI patients in pre-hospital settings (Table 7). A lack of GCS assessment may reduce awareness of the change of neurologic status in TBI patients and relevant interventions may be delayed.

Hyperventilation is the main therapy recommended to control elevated ICP.[12]In China, practice of hyperventilation was only reported by one of the identified papers.[45]Although mannitol has long been proven as an effective tool for reducing ICP, there is no evidence to support its use in pre-hospital settings.[12]In addition, the osmotic diuresis that accompanies mannitol administration may lead to hypotension, especially in hypovolemic patients, and may worsen secondary brain injury in TBI patients.[95]However, this review found that 60 (92%) identi fi ed papers used mannitol to control ICP in pre-hospital settings. Twenty-eight (43%) papers even reported that they administered mannitol to all of their TBI patients (Table 7).

Even though the use of corticosteroids in pre-hospital settings has been proven harmful for TBI patients,[96]22 (34%) papers reported the use of corticosteroids (Table 7). Similarly, albumin was associated with higher mortality rates than normal saline (RR=1.63) in TBI,[97]but it is popular in Chinese pre-hospital settings.

Other interventions

Guidelines indicated that adequate sedation and analgesia were essential in TBI patients, especially if they were ventilated.[14]In China, sedation and analgesia were only reported by 14 (22%) and 6 (9%) identified papers respectively.

Hypertension in TBI patients is usually caused by inadequate sedation and analgesia, and vasodilating agents should be avoided in TBI patients since these may cause fatal hypotension.[14]Three of the identi fi ed papers reported the use of vasodilating agents for TBI patients. The agents used were sodium nitroprusside, nifedipine, and reserpine.[25,43,77]These agents may worsen secondary brain injury and lead to a poor prognosis for TBI patients.

Other medications such as naloxone and sodium bicarbonate, and practices such as the prevention of reflux of cerebrospinal fluid leak and ice cap were not commonly recommended in the pre-hospital TBI guidelines from other countries. More research needs to be done to determine if these practices are appropriate in pre-hospital TBI management.

In summary, we found problems in the current practices of pre-hospital TBI management in China. This suboptimal pre-hospital emergency management may contribute to the high proportion of poor outcomes in TBI in China.

LIMITATIONS

Several limitations of this review should be acknowledged. First, this is a literature review and most likely does not represent the true state of TBI care in the pre-hospital settings in China. Second, this review mainly focused on pre-hospital care of TBI in China, which limits generalizing our fi ndings to other countries. Last, the studies we identified in this review used different approaches to quantify pre-hospital practice across China, and therefore it is not appropriate to quantitatively combine the results.

In conclusion, current practices of pre-hospital TBI management in China are sub-optimal and vary considerably, which may lead to a higher proportion of TBI patients with poor outcomes. Hence, appropriate training programs are urgently needed in China.

Funding:None.

Ethical approval:Not needed.

Conflicts of interest:The authors declare that no competing interest and no personal relationships with other people or organizations that could inappropriately in fl uence their work.

Contributors:Kou K and Hou XY designed the study, Kou Kou analyzed the literatures and drafted the manuscript, Hou XY, Sun JD and Chu K revised the manuscript.

REFERENCES

1 Ghajar J. Traumatic brain injury. Lancet 2000; 356: 923–929.

2 Maas AI, Stocchetti N, Bullock R. Moderate and severe traumatic brain injury in adults. Lancet Neurology 2008; 7: 728–741.

3 Wang CC, Schoenberg BS, Li SC, Yang YC, Cheng XM, Bolis CL. Brain injury due to head trauma: epidemiology in urban areas of the People's Republic of China. Arch Neurol-Chicago 1986; 43: 570–572.

4 Wu X, Hu J, Zhuo L, Fu C, Hui G, Wang Y, et al. Epidemiology of traumatic brain injury in eastern China, 2004: a prospective large case study. J Trauma Inj Infect Crit Care 2008; 64: 1313–1319.

5 Zhao J, Tu EJ-C, McMurray C, Sleigh A. Rising mortality frominjury in urban China: demographic burden, underlying causes and policy implications. Bull World Health Organ 2012; 90: 461–467.

6 Bruns J, Hauser WA. The epidemiology of traumatic brain injury: a review. Epilepsia 2003; 44: 2–10.

7 Andriessen TMJC, Horn J, Franschman G, Naalt J, Iain H, Jacobs B, et al. Epidemiology, severity classification, and outcome of moderate and severe traumatic brain injury: a prospective multicenter study. J Neurotraum 2011; 28: 2019–2031.

8 Marshall LF, Gautille T, Klauber MR, Eisenberg HM, Jane JA, Luerssen TG, et al. The outcome of severe closed head injury. Special Supplements 1991; 75: S28–S36.

9 Miller JD, Butterworth JF, Gudeman SK, Faulkner JE, Choi SC, Selhorst JB, et al. Further experience in the management of severe head injury. J Neurosurg 1981; 54: 289–299.

10 Stocchetti N, Furlan A, Volta F. Hypoxemia and arterial hypotension at the accident scene in head injury. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 1996; 40: 764–767.

11 Queensland Ambulance Service. Clinical Practice Manual, Trauma. Updated 2011. Available at: https://ambulance.qld.gov. au/medical/pdf/09_cpg_trauma.pdf.

12 Brain Trauma Foundation. Guidelines for pre-hospital management of traumatic brain injury. 2nd ed. Updated 2008. Available at: https://www.braintrauma.org/coma-guidelines/ searchable-guidelines/.

13 Procaccio F, Stocchetti N, Citerio G, Berardino M, Beretta L, Corte FD, et al. Guidelines for the treatment of adults with severe head trauma (part I): Initial assessment; evaluation and pre-hospital treatment; current criteria for hospital. J Neurosurg Sci 2000; 44: 1–10.

14 Piek J. Guidelines for the pre-hospital care of patients with severe head injuries. Intens Care Med 1998; 24: 1221–1225.

15 Maas AIR, Ohman J, Persson L, Servadei F, Stocchetti N, Unterberg A, et al. EBIC–Guidelines for management of severe head injury in adults. Acta Neurochir 1997; 139: 286–294.

16 Hou XY, Lu C. The current workforce status of prehospital care in China. Journal of Emergency Primary Health Care 2005; 3.

17 Li J. Resource compare and analysis bteween CNKI, Weipu, and Wanfang database. Information Research 2011; 4: 59–61.

18 Menon DK, Schwab K, Wright DW, Maas AI. Position statement: definition of traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehab 2010; 91: 1637–1640.

19 Lo SM, Yu YM, Lee LYL, Wong MLE, Chair SY, Kalinowski EJ, Chan TSJ. Overview of the Shenzhen Emergency Medical Service Call Pattern. World J Emerg Med 2012; 3: 251–256.

20 Zhang K. Pre-hospital rescue for 94 acute brain trauma patients (in Chinese). Health Must-read 2013; 12: 216.

21 Pan B. Pre-hospital management of brain trauma (in Chinese). China Practical Medicine. 2011; 6: 218–219.

22 Liu Y. Pre-hospital rescue process for trauma patients in primary hospitals (in Chinese). Modern Medicine Journal of China 2011; 13: 83–84.

23 Hui J, Sun J. Pre-hospital management of traumatic brain injury: with 478 case reports (in Chinese). Journal of Yanan University 2009; 7: 2.

24 Zhao Y, Wang M, Jiang H, et al. Causes of traumatic brain injury and pre-hospital management (in Chinese). People's Military Surgeon 2009; 52: 125–126.

25 Ying H. Pre-hospital management of 360 acute traumatic brain injury patients (in Chinese). Chinese Community Doctors 2009; 11: 1.

26 Tang XM. Acute brain injury in pre-hospital care. Guide of China Medicine 2011; 9: 29–30.

27 Wang J. Prehospital management of 105 acute traumatic brain injury patients (in Chinese). Chinese Journal of Practical Nervous Diseases 2007; 10: 83–84.

28 Chen W, Zeng J, Shi Z, Yan Y. Standardised pre-hospital management for 30 open traumatic brain injury patients (in Chinese). Contemporary Medicine 2011; 17: 13–14.

29 Zhuang L. Treatment and nursing care of traumatic brain injury in pre-hospital settings (in Chinese). Journal of Modern Medicine and Health 2009; 25: 3803.

30 Zhang K, Zhang Y. Pre-hospital management of 437 acute traumatic brain injury patients (in Chinese). Medicine Journal of Chinese People's Health 2010; 22: 1058.

31 Xu J. Pre-hospital management of severe traumatic brain injury (in Chinese). Journal of Guangxi Traditional Chinese Medical 2011; 14: 29–30.

32 Lin J, Hu W, Ye J. Prehospital medical care for severe cranial injury in 385 cases. Journal of Traumatic Surgery 2001; 3: 129.

33 Kam CW, Lai CH, Lam SK, So FL, Lau CL, Cheung KH. What are the ten new commandments in severe polytrauma management? World J Emerg Med 2010; 1: 85–92..

34 Zeng Y. Pre-hospital management of severe brain injury (in Chinese). Medical Information 2011; 24: 4977.

35 Yao L, Liu H, Hu X. Patterns of pre-hospital rescue in severe traumatic brain injury (in Chinese). Medicine Industry Information 2005; 2: 103–104.

36 Zeng X. Pre-hospital management of severe brain trauma (in Chinese). Jilin Medical Journal 2012; 33: 7517–7518.

37 Liu Y, Yang G. Pre-hospital management of 24 acute severe traumatic brain injury patients (in Chinese). Public Medical Forum Magazine 2009; 13: 1161.

38 Huang H. Pre-hospital care experience of acute severe craniocerebral injury. China Modern Medicine 2011; 18: 28–30.

39 Tong Y, Pu W. Pre-hospital management of severe brain trauma patients (in Chinese). Zhejiang Journal of Traumatic Surgery 2005; 10: 479.

40 Kong Z, Liu X, Liu J. Pre-hospital first aid to patients with severe traumatic brain injuries in traffic accidents: a report of 985 cases. Acta Medicinae Sinica 2011; 24: 685–687.

41 Shang C. Pre-hospital management of 31 severe traumatic brain injury patients (in Chinese). Jilin Medical Journal 2011; 32: 4193–4194.

42 Han Z, Zhuang Z, Qiao J. Analysis of pre-hospital management in 126 resident severe brain injury patients (in Chinese). Henan Journal of Surgery 2004; 10: 77–78.

43 Dong W, Sun D, Wu Y. Pre-hospital management of 40 severe traumatic brain injury patients (in Chinese). In: The 2004 National Conference on Critical Care Emergency Medicine; 2004.

44 Zeng W. Pre-hospital management of acute severe brain injury (in Chinese). Journal of Clinical Emergency Call 2002; 3: 45–46.

45 Wu B. Analysis of pre-hospital management in 28 129check number traumatic brain injury patients (in Chinese). Chin J Emerg Med 2005; 14: 1053.

46 Du J, Li B. Efficiency of pre-hospital traumatic brain injurymanagement (in Chinese). Chinese Remedies and Clinics 2009; 9: 337.

47 Yang D, Chen H. Analysis of pre-hospitalization emergency treatment of patients of craniocerebral injury before and after Wenchuan earthquake. Medical Journal of West China 2010; 22: 1032–1034.

48 Hu Z, Yi S. Analysis of pre-hospital management in 126 severe traumatic brain injury patients (in Chinese). Chinese Community Doctors 2002; 10: 10.

49 Yang X, Zhao K, Mai Q. Pre-hospital management of severe brain injury complicated with multiple injuries in traffic accidents (in Chinese). China Practical Medicine 2011; 6: 72–73. 50 Zhu J. Pre-hospital treatment of severe brain trauma patients (in Chinese). Guide of China Medicine 2010; 8: 72–73.

51 Yang C. A summary of clinical analysis in pre-hospital management of severe brain trauma patients (in Chinese). Medical Innovation of China 2011; 8: 121–122.

52 Hu Z, Deng Y, Jiang W, Gu Y. Effects of professional prehospital emergency treatment on prognosis in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. Journal of Traumatic Surgery 2009; 11: 232–234.

53 Wang H, Zhang W, Guo Z. Pre-hospital management of 67 severe traumatic brain injury patients (in Chinese). China Medical Herald 2007; 4: 39–40.

54 Jin X. Discussion of the head injury treatment in pre-hospital settings (in Chinese). Harbin Pharmaceutical 2007; 27: 2.

55 Wei Y. Influence of pre-hospital rescue on the recovery of neurological function in severe traumatic brain injury patients (in Chinese). Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine on Cardio-/ Cerebrovascular Disease 2012; 10: 1403–1404.

56 Zhang M, Ma B, Gong X, Chu C. Research into pre-hospital emergencies with acute severe brain injury. Chinese Journal of General Practice 2010; 5: 649–650.

57 Liang K. Pre-hospital management of severe traumatic brain injury (in Chinese). Youjiang Medical Journal 2013; 41: 44–45.

58 Guo W, Yang DM, Liang ZJ, Lin JM, Guo MJ, Li P, et al. Effect of pre-hospital emergency treatment on prognosis in patients with severe craniocerebral trauma. Lingnan Journal of Emergency Medicine 2007; 12: 23–24.

59 Zheng B. Prehospital management of 100 traumatic brain injury patients (in Chinese). In: The Third Session of the National Emergency Traumatology Academic Communication 1999: 220–221.

60 Xu Y. Management of 102 traumatic brain injury patients complicated with multiple injuries (in Chinese). Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine 2008; 7: 61.

61 Yang Q, Du J. Prehospital management of 45 traumatic brain injury patients (in Chinese). Shandong Medical Journal 2005; 45: 84.

62 Wang L, Zhou H, Zhu JF. Application of emergency severity index in pediatric emergency department. World J Emerg Med 2011; 2: 279–282.

63 Gao H, Duan W. Pre-hospital management of 107 severe brain injury patients (in Chinese). Guide of China Medicine 2009; 7: 102–103.

64 Hua H. Pre-hospital management of acute severe traumatic brain injury (in Chinese). Clinical Medicine 2004; 24: 51–52.

65 Cai P, Xiang L, Lei S, Wang S. Pre-hospital management of severe traumatic brain injury (in Chinese). Laboratory Medicine and Clinic 2010; 7: 1621–1622.

66 Li H, Zhou M. Prehospital management of 33 severe traumatic brain injury patients (in Chinese). Guide of China Medicine 2012; 10: 141–142.

67 Huang Y. Analysis of pre-hospital management in 216 severe traumatic brain injury patients (in Chinese). Hei Long Jiang Medical Journal 2013; 37: 268–269.

68 Pi H, Liao W. Pre-hospital management of 202 severe traumatic brain injury patients (in Chinese). Journal of Modern Clinical Medicine 2005; 31: 160.

69 Ge H, Tao X, Zhu J. Analysis of pre-hospital management in 120 brain trauma patients (in Chinese). Medical Information 2010; 23: 4929.

70 Wu W, He Y, Liang J. Pre-hospital management of 87 severe traumatic brain injury patients (in Chinese). Hebei Medicine 2007; 13: 977–978.

71 Yang X. Pre-hospital management of severe traumatic brain injury (in Chinese). Modern Journal of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine 2007; 16: 5142.

72 He Q, Li Q. Pre-hospital management of severe brain injury patients complicated with shock (in Chinese). Journal of Clinical Emergency Call 2006; 7: 143–144.

73 Ji X, Li Y, Zhao S, Wei Z, Liu T, Meng X. Pre-hospital management of severe brain injury patients (in Chinese). Chinese Journal of Clinical Neurosurgery 2004; 9: 389–390.

74 Wang Z, Li C. Pre-hospital management of severe traumatic brain injury (in Chinese). Zhejiang Journal of Traumatic Surgery 2004; 9: 276.

75 Cui X, Ran Z, Yi D, Chen G. Pre-hospital emergency management of severe traumatic brain injury (in Chinese). Chinese Journal of Emergency Medicine 2004; 13: 63.

76 Li W, Huang J, Zhou W, Li J, Wei L, Zhao H. Prehospital care and emergency treatment of critical craniocerebral trauma. Chinese Journal of Trauma 2005; 21: 128–130.

77 Zhang M, Zeng Y, Zhang A, He Y. Probe into the pre-hospital security management of patients with acute craniocerebral trauma. Modern Hospital 2013; 13: 141–142.

78 Hu Z, Zhang Z. The in fl uence of pre-hospital management on the outcome of severe traumatic brain injury patients (in Chinese). China Practical Medicine 2010; 5: 228–229.

79 Liang D. The influence of pre-hospital management for the outcome of severe traumatic brain injury patients (in Chinese). Journal of Youjiang Medical College for Nationalities 2002; 24: 702.

80 Zhou Y, Wu J, Zhen Y, Li G, Huang Z, Zeng B. The influence of pre-hospital and in-hospital emergency medicine pattern on the treatment level of severe traumatic brain injury (in Chinese). Journal of Southern Medical University 2009; 29: 341–345.

81 Huang A, Huang Y. The influence of pre-hospital management on the outcome of severe traumatic brain injury patients (in Chinese). Journal of Medical Theory and Practice 2005; 18: 281–282.

82 Chen B, Kan J, Chen Q. Experience in pre-hospital fi rst aid for 30 cases of severe cranial-cerebral trauma. Modern Hospital 2012; 12: 27–28.

83 Liao Y. Analysis of pre-hospital management in severe traumatic brain injury (in Chinese). Chinese Journal of Practical Nervous Diseases 2012; 15: 50–51.

84 Chen R. Prehospital management of 78 traumatic brain injurypatients complicated with hypovolemic shock (in Chinese). Journal of Medical Theory and Practice 2011; 24: 2686–2687.

85 Chesnut RM, Marshall LF, Klauber MR, Blunt BA, Baldwin N, Eisenberg HM, et al. The role of secondary brain injury in determining outcome from severe head injury. Journal of Trauma 1993; 34: 216–222.

86 Bulger EM, Nathens AB, Rivara FP, Moore M, MacKenzie EJ, Jurkovich GJ. Management of severe head injury: Institutional variations in care and effect on outcome. Crit Care Med 2002; 30: 1870–1876.

87 Ma D, Xi Z, Zhai F, Wang H, Li H. The outcomes and the fi rst aid errors before hospitalization on severe head injury. Chinese Journal of Misdiagnostics 2001; 1: 974–976.

88 Bulger EM, Copass MK, Sabath DR, Maier RV, Jurkovich GJ. The use of neuromuscular blocking agents to facilitate prehospital intubation does not impair outcome after traumatic brain injury. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 2005; 58: 718–724.

89 Von Elm E, Schoettker P, Henzi I, Osterwalder J, Walder B. Pre-hospital tracheal intubation in patients with traumatic brain injury: systematic review of current evidence. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2009; 103: 371–386.

90 Walls RM, Murphy MF. Rapid sequence intubation. In: Manual of Emergency Airway Management (4th ed). 2012; 221.

91 Helm M, Schuster R, Hauke J, Lampl L. Tight control of prehospital ventilation by capnography in major trauma victims. Brit J Anaesth 2003; 90: 327–332.

92 Davis DP, Dunford JV, Ochs M, Park K, Hoyt DB. The use of quantitative end-tidal capnometry to avoid inadvertent severe hyperventilation in patients with head injury after paramedic rapid sequence intubation. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 2004; 56: 808–814.

93 Vassar MJ, Perry CA, Holcroft JW. Prehospital resuscitation of hypotensive trauma patients with 7.5% NaCl versus 7.5% NaCl with added dextran: a controlled trial. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 1993; 34: 622–633.

94 Cooper DJ, Myles PS, McDermott FT, Murray LJ, Laidlaw J, Cooper G, T et al. Prehospital hypertonic saline resuscitation of patients with hypotension and severe traumatic brain injury. JAMA 2004; 291: 1350–1357.

95 White H, Cook D, Venkatesh B. The use of hypertonic saline for treating intracranial hypertension after traumatic brain injury. Anesth Analg 2006; 102: 1836–1846.

96 Roberts I, Yates D, Sandercock P, Farrell B, Wasserberg J, Lomas G, et al. Effect of intravenous corticosteroids on death within 14 days in 10008 adults with clinically signi fi cant head injury (MRC CRASH trial): randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2004; 364: 1321–1328.

97 SAFE Study Investigators1, Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials Group, Australian Red Cross Blood Service, George Institute for International Health, Myburgh J, Cooper DJ, et al. Saline or albumin for fluid resuscitation in patients with traumatic brain injury. N Engl J Med 2007; 357: 874–884.

Received May 1, 2014

Accepted after revision October 28, 2014

Correction

We apoplogize for an error in the article Life-threatening complications of ascariasis in trauma patients: a review of the literature by Quan-yue Li et al (World J Emerg Med, 2014, Vol 5, No 3, 165–170), the phrase "in 2 cases after operation" should have been removed.

World J Emerg Med 2014;5(4):245–254

10.5847/wjem.j.issn.1920–8642.2014.04.001

World journal of emergency medicine2014年4期

World journal of emergency medicine2014年4期

- World journal of emergency medicine的其它文章

- Instructions for Authors

- A man with a fracture from minor trauma

- A minimally invasive multiple percutaneous drainage technique for acute necrotizing pancreatitis

- Effects of mild hypothermia on the ROS and expression of caspase-3 mRNA and LC3 of hippocampus nerve cells in rats after cardiopulmonary resuscitation

- Simvastatin inhibits apoptosis of endothelial cells induced by sepsis through upregulating the expression of Bcl-2 and downregulating Bax

- Heat-related illness in Jinshan District of Shanghai: A retrospective analysis of 70 patients