为爱结婚

by Tessa Hadley

特莎·哈德利(Tessa Hadley),英国女作家。1957年出生于英格兰布里斯托尔一个文学艺术氛围浓厚的家庭。曾就读于剑桥大学,主修英国文学,获得巴斯斯巴大学文学创作硕士学位。目前就职于该大学,教授文学和写作。其主要代表作品有:长篇小说处女作《家中事故》(2002),曾入围《卫报》小说新人奖;长篇小说《一切都会好起来》(2003)和《主卧室》(2007);短篇小说集《中暑》(2007)以及文学评论集《亨利·詹姆斯和性幻想》(2002)。除此之外,她还为英国BBC广播电台创作过一个剧本——《温蒂屋》(2005)。

哈德利热衷于描述家庭关系的紊乱以及这种紊乱所造成的后果。她一直试图用自己的文字在有限的可能范围内警示女性应当如何选择生活并以怎样的生活态度在社会中立足。与此同时,哈德利还时常批判一些不知感恩的年轻一代。

这些写作风格在《为爱结婚》中可谓尽显:一个是不顾家人反对选择了跟与自己父亲年龄相仿的男人结婚的新娘洛蒂,一个是身边围绕着各种花草蝴蝶、张口闭口都是艺术的再婚老新郎埃德加,这对从头顶发髻到脚底毛完全不和谐的新婚夫妇在婚后的生活一如我们所预料的那样:多子、肥胖、贫穷、世俗、乏味且频临触礁。而以哈德利的写作习惯,我们不难想象,这种连主流社会都会糅以鄙视的婚姻又能存活多久?为“爱”结婚不假,殊不知,爱也跟英语考试一样,它分级!

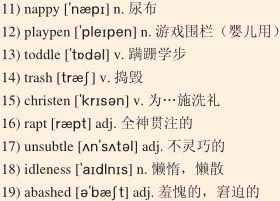

The wedding was held in a registry office, with a blessing at a church afterward; Edgar insisted on the Elizabethan prayer book and the Authorized Version of the Bible. He composed, for the occasion, a setting for Spensers“Epithalamion” and one of his students sang it at the reception, which was in a sixteenth-century manor house with a famous garden that belonged to the university.

Lottie was wearing 1)contact lenses and, without her glasses, her face seemed weakly, 2)blandly expectant. A white flower fastened behind her ear slid gradually down her cheek during the course of the afternoon until it was bobbing against her chin. She clung to Edgar with uncharacteristic little movements, touching at his hand with her fingertips, dropping her forehead to rest against his upper arm while he spoke, or throwing back her head to gaze into his face.

“It wont last,” Duncan reassured his other children.

To Edgars credit, he seemed 3)sheepish under the familys 4)scrutiny, and did his best to 5)jolly Lottie along, circulating with her arm tucked into his, playing the gentle public man, distinguished in his extreme thinness, his suit made out of some kind of rough gray silk. You would have picked him out in any gathering as subtle and thoughtful and well informed. But there werent really quite enough people at the reception to make it feel like a success: the atmosphere was constrained; the sun never came out from behind a mottled thick lid of cloud. After the drink ran out and the students had melted away, too much 6)dispiriting white hair seemed to show up in the knots of guests remaining, like snow in the flower beds. Duncan overheard someone, sotto voce, refer to the 7)newlyweds as “Little Nell and her grandfather.”

Valerie phoned Lottie a week or so after the wedding to ask whether she knew that Edgar had tried the same thing the year before with the student who had sung at the reception, a tall beautiful black girl with a career ahead of her. Everyone knew about this because Valerie had also telephoned Hattie. When Hattie asked Lottie about it, Lottie only made one of her horrible new gestures, folding her hands together and letting her head droop, smiling secretively into her lap. “Its all right, Mum,” she said. “He tells me everything. We dont have secrets. Soraya is an exceptional, gifted young woman. I love her, too.”

Hattie hated the way every opinion Lottie offered now seemed to come from both of them: we like this; we always do that; we dont like this. They didnt like supermarkets; they didnt like Muzak in restaurants; they didnt like television costume dramas. As Duncan put it, they generally found that the modern world came out disappointingly below their expectations. Hattie said that she wasnt ready to have Edgar in her house yet.

The university agreed that it was acceptable for Lottie to continue with her studies, as long as she didnt take any of Edgars classes; but, of course, he carried on working with her on her violin playing. Her old energy seemed to be directed inward now; she glowed with the promise of her future. She grew paler than ever, and wore her hair loose, and bought silky indeterminate dresses at the 8)charity shops. Hattie saw her unexpectedly from behind once and thought for a moment that her own daughter was a stranger, a stumpy little child playing on the streets in clothes from a dress-up box. Edgar and Lottie were renting a flat not far from Hattie and Duncan, tiny, with an awful galley kitchen and the landlords furniture, but filled with music. He and Lottie were pretty hard up, but at first they carried this off, too, as if it were a sign of something rare and fine.

“God knows what they eat,” Hattie said.“Lottie doesnt know how to boil an egg. Probably Edgar doesnt know how to boil one, either. Ill bet hes had women running around him all his life.”

Then Lottie began to have babies. Familiarity had just started to silt up around the whole improbable idea of her and Edgar as a couple—high-minded, humorless, poignant in their unworldliness—when everything 9)jolted onto this new track. Three diminutive girls arrived in quick succession, and life at Lottie and Edgars, which had seemed to drift with eighteenth-century underwater slowness, snapped into noisy, earthy, and chaotic contemporaneity.

Lottie in pregnancy was as swollen as a beach ball; afterward, she never recovered her neat boxy little figure, or that dreamily 10)submissive phase of her personality. She became bossy, busy, cross; she abandoned her degree. She chopped off her hair with her own scissors, and mostly wore baggy tracksuit bottoms and T-shirts. Their tiny flat was submerged under packs of disposable 11)nappies, cots, toys, washing, nursing bras and breast pads, a 12)playpen, books on babies, books for babies. The tenant below them left in disgust, and they moved downstairs for the sake of the extra bedroom. As soon as the girls could 13)toddle, they 14)trashed Edgars expensive audio equipment. He had to spend more and more time in his room at the university, anyway—he couldnt afford to turn down any commissions. Now Lottie spoke with emotion only about her children and about money.

The girls were all 15)christened, but Lottie was more managerial than 16)rapt during the ceremonies: Had everyone turned up who had promised? With the fervor of a convert to practicality, she planned her days and steered through them. Duncan taught her to drive, and she bought a battered old Ford Granada, 17)unsubtle as a tank, and fitted it with child seats, ferrying the girls around from nursery to swimming to birthday parties to baby gym. She was impatient if anyone tried to turn the conversation around to art or music, unless it was Tiny Tots ballet. She seemed to be carrying around, under the surface of her intolerant contempt for 18)idleness, a burning unexpressed message about her used-up youth, her put-aside talent.

“She ought to be 19)abashed,” Hattie said once. “We warned her. Instead, she seems to be angry with us.”

Hattie had been longing for early retirement, but she decided against it, fearing that the empty days might only fill up with grandchildren. She believed that in the mirror she could see the signs in her face—like threads drawn tight—of the strain of these extra years of teaching that she had not wanted.

婚礼在婚姻登记处举行,随后再到教堂接受牧师的祝福。埃德加坚决要求用伊丽莎白时代的祈祷书和《钦定版圣经》。他临时谱曲,以斯宾塞的诗《婚后曲》为词,让他的一个学生在婚宴上演唱。婚宴设在一个16世纪的庄园里,里面有个著名的花园,现归大学所有。

洛蒂戴上了隐形眼镜,去掉框架眼镜,她的脸似乎柔柔淡淡地充满了期待。别在耳后的一朵白花在一下午的婚礼中沿着她的脸颊一点点往下滑,最后滑到下巴之际动弹着。她挽着埃德加,动作纤巧,与平素判若两人:用指尖轻触他的手,在他说话时,垂下头用前额贴着他的上臂,或是扬起头凝视他的脸。

“不会长久的。”邓肯跟他的另外几个孩子打包票。

为埃德加增光的是,在全家人的密切注视下他显得很腼腆。他竭力哄洛蒂开心,挽着她的胳膊四处周旋,扮演着彬彬有礼的公众人物角色。他穿着粗糙的灰色丝质礼服,因为极其瘦削而格外引人注目。在任何聚会场合里,他总能给人一种细腻体贴且见多识广的印象。只是出席婚宴的人不是很多,难以让人觉得办得很成功:气氛有些拘谨,太阳也一直没有从斑驳的厚云层中露出脸来。喜酒喝毕,学生逐渐散去后,剩下的宾客大多白发斑斑,像花床上的雪,暮气煞人。邓肯无意中听到有人压低嗓音说这一对新人像“小耐儿和她的外公”。

婚礼结束后的一个星期左右,瓦莱丽给洛蒂打了电话,问她是否知道埃德加一年前也曾向那个在其婚宴上唱歌的学生示爱。那是个高挑漂亮、前程似锦的黑人女孩。这件事人人皆知,因为瓦莱丽也给哈蒂打过电话。当哈蒂对洛蒂提起此事时,洛蒂只是摆了个令人生厌的新姿势:双手交叠起来,垂下头窃笑。“没事儿的,妈妈,”她说,“他对我无所不谈。我们之间没有秘密。索拉雅很出色,是个有才华的年轻姑娘。我也喜欢她。”

现在洛蒂每发表一个看法都像是两人的意见,这让哈蒂很厌恶。我们喜欢这个;我们总是那样做;我们不喜欢这个。他们不喜欢逛超市;他们不喜欢餐厅里放的背景轻音乐;他们不喜欢古装电视剧。如邓肯所言,他们普遍认为现代社会的水准低于期望值,令人扫兴。哈蒂说她一时还接受不了这个新女婿。

大学同意洛蒂继续学业,只是规定其不能选修埃德加所授的任何课程;当然,他还是会继续指导洛蒂拉小提琴。她往日的活力现在似乎收敛了;她因前途光明而暗生喜悦。她脸色比从前更加苍白,头发松散开来,穿着从慈善商店买的那些来路不明的丝质衣服。哈蒂有次不经意间瞧见了她的背影,有那么一会儿还以为自己的女儿是个陌生人——一个穿着从玩具娃娃换装衣橱里挑来的服饰,在街头玩耍的矮胖小孩。埃德加和洛蒂在距离她父母家不远处租了套小公寓,厨房窄得可怜,家具也是房东的,只是弥漫着音乐。他和洛蒂的生活非常拮据,但至少有自己的小窝,像是什么稀罕好东西似的。

“天知道他们都吃些什么,”哈蒂说,“洛蒂连只鸡蛋都不会煮,埃德加可能也不会。我敢说他这辈子一直都有女人为他忙东忙西。”

这时,洛蒂开始生孩子了。她和埃德加清高严肃、完全不谙世事,整桩婚事看起来就难以想象,正当人们刚开始接受他俩结合的事实,一切又沿着新的道路颠簸前进了。三个娇小的女婴很快就一个接一个地降生了。此前,洛蒂和埃德加的生活像18世纪的一股暗流悠缓涌动,现在却快速进入了喧闹、世俗而嘈杂的现代社会。

怀孕时的洛蒂胖得像个沙滩球,生完孩子后再也没有恢复成原来灵巧、娇小微丰的身材,她性格中温顺的梦幻时期也过去了。她变得专横、忙碌、爱发脾气,学业也放弃了。她自己用剪子把长发剪掉,大多数时间穿着肥大的运动裤和T恤衫。他们的蜗居彻底沦陷,堆满了成捆的尿不湿、婴儿床、玩具、脏衣服、哺乳乳罩及乳贴、婴儿围栏、育儿图书和宝宝读物。住在他们楼下的房客出于厌恶而搬走,他们于是搬到下面去,因为那儿有多一个卧室。女孩儿们刚学会走路,就把埃德加价格不菲的音响设备毁掉了。他不得不花越来越多的时间呆在大学的办公室里——他不能推掉任何赚外快的作曲邀约了。现在洛蒂只有在提起孩子和钱的时候才会激动。

三个女儿都接受了洗礼。在洗礼仪式上,洛蒂为这天的安排各种操心,根本说不上为洗礼神倾欣喜:答应要来的人都到场了吗?转投世俗实务麾下的她,带着新的激情制订着日程计划,然后一一按本子办事。邓肯教会她开车,她于是买了辆二手的福特格兰纳达,车身像坦克一样不灵活。她装上了儿童车座,就这样载着女孩子们到处转悠:从托儿所到游泳池到生日宴会再到少儿健身房。如果有人试图把话题转向艺术或音乐,她就会变得不耐烦,只有谈起幼儿芭蕾时是个例外。表面上她看不惯也瞧不起懒散行为,实际上那饱含着一个如火般炽热却不曾言说的信息:她的青春耗尽了,天资也荒废了。

“她应该感到羞愧,”哈蒂曾说过,“我们警告过她。而她竟然好像还生我们的气。”

以前哈蒂一直很想早点退休,现在却不愿退休了。她怕空闲的日子会被外孙女们填满。她相信从镜中自己的脸上就能看出征兆——就像绷紧的绳子——过度的压力造成的,原本不想上课了却还要再多教几年了。