数理界性别鸿沟之新探

By Scott Simon

Scott Simon (Host): Ever since experts became aware of a gender gap in science and technology, theyve been trying to figure out whos to blame. Often the blame has been placed on old fashioned sexism. What amounts to a boys club in many sciences and technologies that excludes women. But a recent article in The Boston Globe suggests that the answer may be women in western societies have so many opportunities, they freely choose another field.

The writer of that article called “The Freedom to Say No”is Elaine McArdle. She joins us from member station WBUR in Boston. Ms. McArdle, thanks so much for being with us.

Ms. Elaine Mcardle (Writer): Thank you for having me.

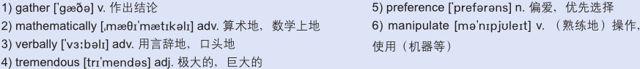

Simon: You described two separate research projects that seemed to come out at the same conclusion that men and women make different choices. Lets talk about the Vanderbilt project first where scientists, I 1)gather, took a look at what happened to 5,000 2)mathematically gifted boys and girls over 30 years.

Ms. Mcardle: Thats right. The two researchers there started more than 30 years ago looking at students were very gifted in math and had scored very high on the math SAT and then followed them over the next decade to see the career choices and educational choices that they made.

Simon: And?

Ms. Mcardle: Well what they found was that the men tended to go into engineering, math, and computer science and then women tended to go into medicine and biological sciences or not to be in science at all.

Simon: And what were some of the motivating factors?

Ms. Mcardle: One of the interesting findings was that women who are very, very good at math also tend to be very good 3)verbally so that their career options are broader than men. Men who are very good at math tend to not be as good as women in verbal skills. So that a woman whos 4)tremendous at math could be a doctor, could be an engineer but she could also be a lawyer or she could do something entirely different altogether.

Simon: You also site the research of someone named Joshua Rosenbloom whos an economist at the University of Kansas. What was his project?

Ms. Mcardle: Joshua Rosenbloom developed a study that looked at computer careers, IT careers to look at why there were fewer women in that field than men. And what he found, what he and his colleagues found was that the single biggest factor was 5)preference, what women prefer to do at work.

Simon: Now would it be fair to say that women just enjoy working with people in greater percentage?

Ms. Mcardle: That is what both of these studies found. The IT study, for example, found that most of the time women prefer to work with other people or other kinds of organic situations where men most of the time prefer to work in inorganic situations, 6)manipulating tools and that kind of thing.

Simon: You described another study by the Canadian psychologist Susan Pinker that compares countries with more or less freedom of choice for women and what they wind up doing in their careers. What did she find?

Ms. Mcardle: That was particularly interesting in that you might assume that in a country where women were given complete freedom of choice or near to it in careers that they would end up making the same decisions that men did in their careers. What she found was that it was actually not that at all. That in countries where women had a lot of educational opportunity and a lot of freedom of choice, there was a bigger gender gap in the careers that they went into.

Simon: Now there are some people who look at the same numbers and draw different conclusions. Why dont you bring us their arguments too?

Ms. Mcardle: Naturally anyone who looks at this kind of study and these kind of results gets concerned because you worry that it will be used or leaned upon to allow sexism to continue in various fields. What these researchers as I talked with them emphasize—they are not saying that sexism does not exist, theyre saying however, that in the rich stew of someones career choice, preference is something that should be paid attention to that has not really been considered at all.

Simon: Ms. McArdle, thanks so much.

Ms. Mcardle: Thank you very much. It was really enjoyable.

司各特·西蒙(主持人):自从专家们开始意识到在科技界职业生涯上两性之间存在着差距,他们一直想要找出祸根渊源。老套的性别歧视往往被揪出来作为解释,总认为,科技界之所以成为排挤女性的男子俱乐部,正是这种歧视造成的。但是,《波士顿环球》最近刊登的一篇文章提出,也许是因为西方社会的女性拥有太多的发展机会,所以一般会自由地选择理工科技以外的其他行业。

那篇文章名为《拒绝的自由》,其作者依琳·麦卡道今天透过我们在波士顿的兄弟电台WBUR和我们连线。麦卡道女士,你好,谢谢你参与我们的节目。

依琳·麦卡道女士(作家):谢谢你们的邀请。

西蒙:你描述了这么两个独立的研究项目,两者得出的结论是一致的,都是认为男性和女性在事业发展上作出了不同的选择。我们先来谈谈范德堡大学的项目,据我了解,在这项目里,科学家们跟踪研究了5000名数学资优的男女生在三十年间的发展。

麦卡道女士:没错。这项目的两位研究员三十年前就开始挑取那些在数学方面特别有天分,在SAT的数学考试里获取高分的学生作为研究对象,然后一直跟踪观察其接下来的十年里在事业生涯、教育进修上所作的选择。

西蒙:结果呢?

麦卡道女士:他们发现的是,男性一般会进入工程、数学、计算机科学这些领域,而女性则倾向进入药学、生物科学或完全非理科的领域。

西蒙:那驱使他们做出这些选择的都有些什么因素呢?

麦卡道女士:一个有趣的发现是,数学好的女性往往语言表达能力也相当不错,所以她们的事业选择范围要比男性宽广。数学好的男性一般在语言表达上逊色于女性。所以数学资质不凡的女生可以去当医生、工程师,也可以去当律师,或者做一些完全不一样的工作。

西蒙:你还援引了肯萨斯大学一位经济学家乔舒华·罗森布鲁姆所做的一项研究。他的项目是关于什么的呢?

麦卡道女士:乔舒华·罗森布鲁姆针对计算机IT行业做了一个研究,探求这领域里为什么女性比男性少。最后,他和同事们发现这里面最大一个原因是个人偏好,问题全在于女性喜欢选择做什么工作。

西蒙:那是不是说,绝大部分的女性就是喜欢做一些与人打交道的工作呢?

麦卡道女士:这正是那两个研究所得出的结论。比如说,那个IT界的调查就发现在大多数情况下,女性情愿和他人一起工作,或者在其他有机社群环境里工作,而男性则喜欢在无组织机构的环境里工作,操控工具,做那一类的事。

西蒙:你还描述了加拿大心理学家苏珊·平克的一个研究——对女性个人职业选择自由度不同的国家作对比,看其女性最终进入何种职业领域。她的结论是什么呢?

麦卡道女士:你也许会以为在女性可以完全自由或者基本自由选择职业的国度里,她们会和男性做出同样的事业选择。但有趣的是,她发现根本不

是这样。在女性享有充分受教育机会和自由选择权利的国家里,人们在事业发展路径上的性别鸿沟更是明显。

西蒙:对于同样的数字,人们往往会得出不同的结论。你能给我们讲讲他们的论据吗?麦卡道女士:当然,看到这么一种研究和这些结论,人们总会担心这些数据结果会被利用、被依仗,令性别歧视在各行业领域里继续滋生繁衍。我跟这些研究者聊过,他们强调,性别歧视并非不存在,然而,一个人面对事业的多元选择,“喜好”是一个我们值得关注的因素,而此前大家一直忽略考虑这一点。

西蒙:谢谢麦卡道女士。

麦卡道女士:非常感谢。很高兴参与节目。CS