Prevalence and correlated factors of lifetime suicidal ideation in adults in Ningxia, China

Zhizhong WANG, Ying QIN, Yuhong ZHANG, Bo ZHANG*, Lin LI, Tao LI, Li DING

•Original article•

Prevalence and correlated factors of lifetime suicidal ideation in adults in Ningxia, China

Zhizhong WANG1, Ying QIN1, Yuhong ZHANG1, Bo ZHANG2*, Lin LI1, Tao LI1, Li DING1

1. Introduction

Suicidal ideation – thoughts about killing oneself –is a risk factor for suicide[1]that is associated with demographic and other characteristics of the individual.Some reports suggest that religious beliefs are associated with decreased levels of suicidal ideation,[2,3]but it’s uncertain whether or not this is the case in individuals who hold Islamic religious beliefs. Karam and colleagues[4]found that in 12 Arab (Muslim) countries the lifetime prevalence of suicidal ideation and attempts ranged from 2.1 to 13.9% and 0.7 to 6.3%, respectively.The frequently reported low rates of suicide in Muslim countries[5]may be due to under-reporting because suicide is a considered a crime in several of these countries. In Canada – where suicide is not considered a crime – a study of immigrants from India[6]did not fi nd a significant difference in the prevalence of suicidal behaviors between the Muslim immigrant population and the local non-Muslim population.

The Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region is a relatively poor northwestern province of China with a large Hui population that shares the same social system and living environment as the majority Han-ethnicity residents.But the Hui are primarily Muslim while most of the Han residents are atheists, so the cultural traditions of the two groups are quite different. This setting provides an excellent opportunity to assess the potential role of Muslim beliefs on suicidal ideation and behavior, but there has never been a report comparing the prevalence of suicidal ideation in these two ethnic groups.

2. Methods

2.1 Subjects

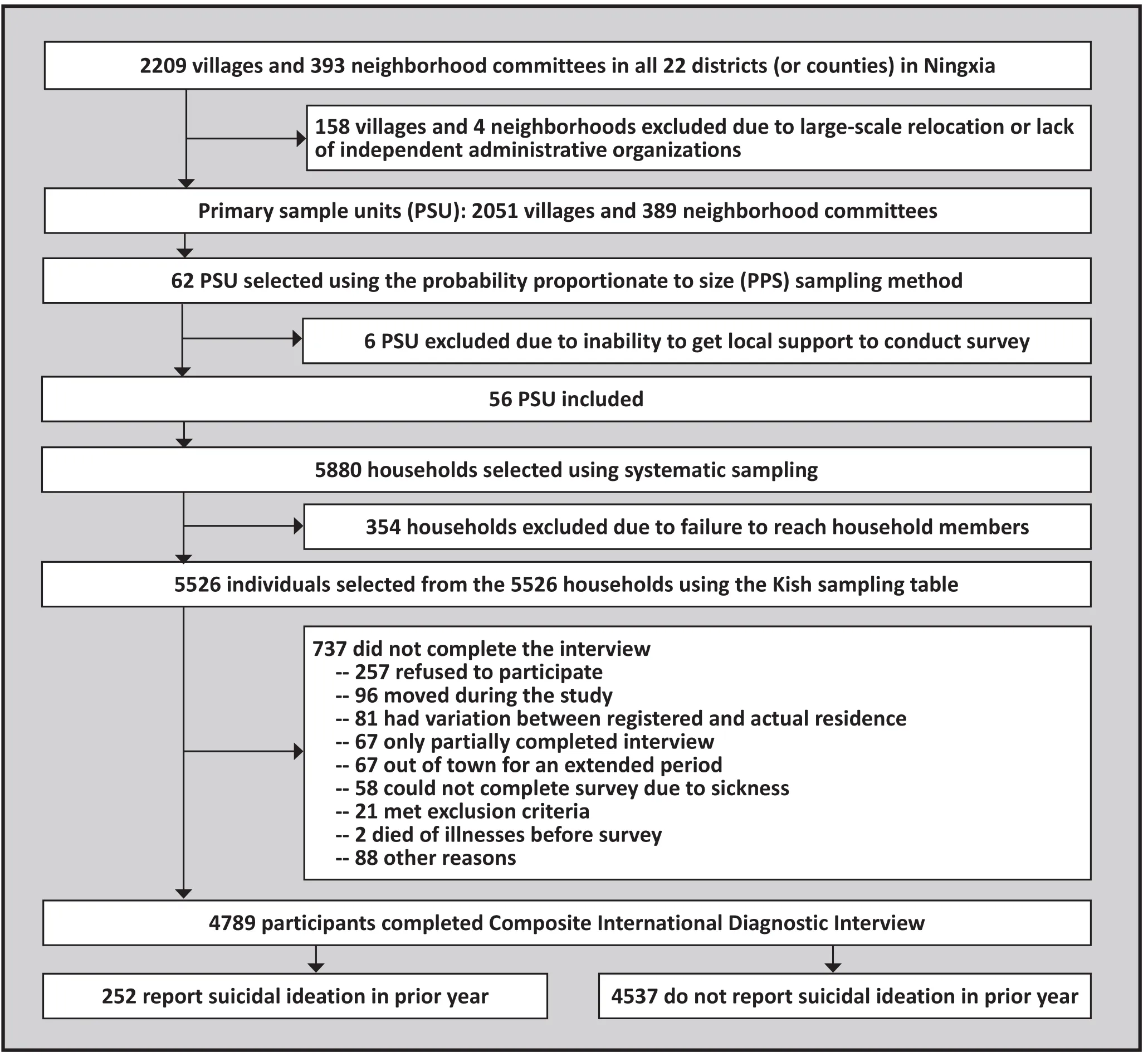

The sample used in this report was identified as part of a province-wide epidemiological study on mental disorders in Ningxia. As shown in Figure 1,participants were selected in three stages. In the first stage, the primary sampling units (PSU) were selected from among all 2209 administrative villages and 393 neighborhood committees in the province (as reported in the 2010 national statistics yearbook[7]).After excluding locations that had experienced largescale relocations (primarily due to urban development)or that were administratively combined with other villages or neighborhoods, 62 villages and regions were selected using probability proportionate to size (PPS)sampling methods by executing the PPS command in the Statistical Analysis Software (SAS) package. In the second stage, 60 to 210 households were selected from each PSU using systematic sampling: 60, 110, 160 and 210 households were selected from PSU that had≤500, 501-1000, 1001-2000, and >2000 households,respectively. A total of 5880 households were selected from the 62 PSU. In the final sampling stage, uniformly trained interviewers went to these 5880 households and used a Kish selection table[8]to randomly select one participant from all adult (i.e., >18 years of age)household members who had lived in the household for at least 6 months. Selected individuals were excluded if they had an obvious language disorder, a history of suffering from an organic mental disorder, or a seriousphysical condition that prevented them from completing the survey. In total, 5526 eligible participants were identified from the 5880 households.

Figure 1. Identification of study participants

2.2 Procedure

The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Ningxia Medical University. A computerassisted version of the interviewer-administered Chinese-language edition of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview[9](CIDI-CAPI) was used in the survey. The first item in the interview is a description of the potential risks and benefits of the survey; after the interviewer reads this description respondents are asked to provide their oral consent for the survey, if they do not provide their consent, the interview is immediately terminated.

Medical students from the Ningxia Medical University were the survey interviewers. Their responsibility was to visit the sampled households, select the target household member, and conduct face-to-face interviews using the CIDI with the identified respondents. All interviewers attended a one-week standardized course on administration of the CIDI; the course provided training in basic interviewing techniques, use of the CIDI questionnaire, correct operation of the computerassisted system, one-on-one practice, and field trials in the community. After the training, the 85 interviewers who passed a written examination about the survey were certified as the interviewers for the survey.

The suicide survey analyzed in this report is a section of the CIDI interview. To encourage participants to frankly answer sensitive questions (like those about suicide), during the survey potentially sensitive questions were provided in a separate booklet that the respondent read before responding to the relevant questions. For example, the three core questions about suicide were named ‘Experience A’ (“Have you seriously considered suicide?”), ‘Experience B’ (“Have you ever had a detailed plan to suicide?”) and ‘Experience C’(“Have you ever attempted suicide?”). When asking about suicide the interviewer directs respondents to the appropriate page in the booklet and first asks them if they have had Experience A; if the response was‘yes’ (i.e., they had had suicidal ideation at some time in the past), the interviewer continues to ask whether or not they have had Experience B and Experience C.(Respondents who deny suicidal ideation are not asked about suicidal plans or suicide attempts.) Whenever the respondent acknowledges one of the experiences, a follow-up question asks whether or not it had occurred in the prior year. If the participant could not read,the interviewer would read out all the questions and choices.

2.3 Questionnaire content and definitions of related variables

The survey also included detailed demographic information, self-reports of health status, and symptom checklists that generated current and lifetime diagnoses of a wide range of common mental disorders. Variables employed in the analysis used in this paper were operationally defined as follows:

(a) Suicidal ideation. Respondent acknowledges seriously considering suicide at some time in the past.

(b) Migrant. Respondent reports moving or being relocated to other counties (or districts) because of national policies or large-scale construction projects, and living in their current location of residence for at least two years.

(c) Residence in mountainous areas. Resident of one of the eight counties in the mountainous Yin Nan region of Ningxia.

(d) Disturbed sleep. Respondent reports that any of the following problems occurred almost every day for at least 2 weeks at any time over the prior year: spending two or more hours falling asleep;waking up in the middle of the night and taking more than one hour to get back to sleep; waking up two hours earlier than necessary; or feeling tired or sleepy during the day.

(e) Mood disorder. Meets ICD-10 diagnostic criteria of depression, hypomania or mania at any time in the prior year.

(f) Other mental disorder. Meets ICD-10 diagnostic criteria of agoraphobia, social phobia, other specified phobia, panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder,alcohol dependence or nicotine dependence at any time in the prior year.

(g) Chronic pain. Respondent reports chronic pain in any part of the body at any time over the prior year.

(h) Self-reported poor health. Respondent rates own health over the last year as ‘poor’ or ‘very poor’.

(i) History of hypertension. Respondent reports having been told by a doctor that he or she had hypertension at any time in the past.

(j) History of diabetes. Respondent reports having been told by a doctor that he or she had diabetes at any time in the past.

2.4 Data analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using version 8.2 of the SAS package. The 95% confidence intervals (CI)of the prevalence of suicidal ideation, suicidal plans,and suicide attempts were estimated using the normal approximation method, and the standardized rates were calculated by adjusting the results to the global standard age distribution reported by the World Health Organization (WHO).[10]Chi-squared tests were used to compare gender, ethnicity, and other factors between respondents who did and did not report suicidal ideation, and t-tests were used to compare the mean age in the two groups. The significance level was set at 0.05, and two-tailed tests were used.

Three separate stepwise logistic regression analyses were conducted to identify the factors independently associated with lifetime suicidal ideation in the total sample and, separately, in the Hui ethnic group and the Han ethnic group. The dependent variable for the regression model was suicidal ideation (1=yes,0=no) and the independent variables considered were gender (1=female, 0=male), ethnicity (1=Hui, 0=Han),age (actual value), marital status (0=not married,1=married, 2=divorced or widowed; ‘not married’was the comparator while ‘married’ and ‘divorced or widowed’ were entered as two dummy variables),level of education (3=illiterate, 2=primary school and junior high school, 1=senior high school or above;treated as a continuous variable), migration status(1=migrant, 0=non-immigrant), location of residence(1=rural, 0=urban), region of residence (1=plains,0=mountainous), self-rated physical health (1=poor,0=well), history of diabetes (1=yes, 0=no), history of hypertension (1=yes, 0=no), chronic pain (1=yes, 0=no),self-rated mental health (1=poor, 0=well), disturbed sleep (1=yes, 0=no), mood disorder (1=yes, 0=no), and other mental disorder (1=yes, 0=no). Gender and age were forced into the models and then all other variables were added in a stepwise fashion with the significance level for entry of a variable set at 0.05 and for removal of a variable set at 0.10.

3. Results

As shown in Figure 1, 4789 participants completed the survey, a response rate of 86.7%. Among the 737 nonrespondents, 257 (35%) refused to participate; most of the others were not located or unable to complete the survey. The participants’ were from 18 to 90 years of age; the average age (sd) was 44.0 (15.5) years.

3.1 Prevalence of self-reported suicidal ideation, plans and attempts

Of the 4789 participants, 252 (5.30%; CI=4.66-5.93%)reported having had seriously considered suicide at some point during their lifetime, 73 (1.52%; CI=1.17-1.86%) reported having made a detailed suicide plan in their lifetime, and 37 (0.77%, CI=0.52%-1.02%) reported having made a suicide attempt in their lifetime. Among these respondents, 94 (1.96%; CI=1.56-2.35%) reported suicidal ideation in the prior year, 34 (0.71%, CI=0.47-0.95%) reported making a detailed suicidal plan in the prior year, and 9 (0.19%; CI=0.07-0.31%) reported having made a suicide attempt in the prior year.

Using the age distribution of the WHO standard global population, the standardized lifetime prevalence of suicidal ideation in Ningxia is 5.75% (CI=5.09-6.41%); 3.25% (CI=2.46-4.04%) for males and 6.57%(CI=5.65-7.49%) for females. This difference by gender is statistically significant (χ2=37.31, p<0.001). The standardized lifetime prevalence of making a detailed suicide plan is 1.47% (CI=1.13-1.81); 0.84% (CI=0.43-1.24%) in males and 1.90% (CI=1.39-2.41%) in females(χ2=9.28, p=0.002). The standardized lifetime occurrence of suicide attempts is 0.92% (CI=0.65-1.19%), 0.85%(CI=0.44-1.24%) in males and 0.98% (CI=0.61-1.34%) in females (χ2=0.27, p=0.601).

The standardized prevalence of lifetime suicidal ideation is 5.92% (CI=4.87-6.96%) in the Hui ethnic group and 4.52% (CI=3.75-5.28%) in the Han ethnic group (χ2=4.79, p=0.029). The standardized lifetime prevalence of making a detailed suicidal plan is 1.93%(CI=1.32-2.54%) in the Hui ethnic group and 1.13%(CI=0.74-1.52%) in the Han ethnic group (χ2=5.33,p=0.021). And the standardized lifetime prevalence of making a suicide attempt is 0.94% (CI=0.51-1.36%) in the Hui ethnic group and 0.60% (CI=0.31-0.88%) in the Han ethnic group (χ2=1.64, p=0.200).

3.2 Comparison of respondents who do and do not report suicidal ideation

Table 1 shows the univariate comparison of the 252 individuals who reported prior suicidal ideation with those of the 4537 respondents who did not report prior suicidal ideation. There was no difference in the ethnicity of the two groups, but respondents who reported prior suicidal ideation were more likely to be female, divorced or widowed, have a higher level of education, live in a rural community, live in a mountainous area, and have a history of hypertension.Individuals who reported lifetime suicidal ideation were also significantly more likely to meet diagnostic criteria for a mood disorder or some other mental disorder in the prior year and to report poor physical or mental health, disturbed sleep, or chronic pain over the prior year. The mean (sd) age of respondents with prior suicidal ideation (46.9 [13.7] years) was significantly higher than that of respondents without prior suicidal ideation (43.9 [15.5] years) (t=3.38, p<0.001).

3.3 Unconditional logistic regression analysis of the factors associated with lifetime suicidal ideation

As shown in Table 2, two factors were independently associated with lifetime suicidal ideation in the total sample and in both of the stratified analyses by ethnicity: presence of a non-mood mental disorder and self-report of poor physical health in the prior year.Residence in a rural community and being divorced or widowed were significantly associated with lifetime suicidal ideation in the full sample but in neither of the stratified analyses. A higher educational attainment was significantly associated with lifetime suicidal ideation in both Han respondents and Hui respondents, but this variable was not included in the logistic regression model for the full sample (possibly because it was strongly associated with the rural residence variable that was in the full model but not in the ethnicity-specific models). Female gender was significantly associated with lifetime suicidal ideation in the full sample and among Han respondents, but not among Hui respondents. The presence of a mood disorder in the prior year was significantly associated with lifetime suicidal ideation in the full sample and in the Hui respondents, but not in the Han respondents. Finally,disturbed sleep over the prior year was significantly associated with lifetime suicidal ideation in Han respondents, but not in Hui respondents or in the full sample.

Table 1. Univariate comparison of adult respondents from Ningxia with and without self-reported suicidal ideation at any point in their lifetime

4. Discussion

4.1 Main findings

This large representative study in Ningxia found a selfreported lifetime prevalence of suicidal ideation of 5.30% which is similar to the 5.93% prevalence reported by Wang and colleagues[11]in rural Shandong Province.We found a higher age-adjusted prevalence of lifetime suicidal ideation in Hui ethnicity respondents than in Han ethnicity respondents – a new finding that has not been reported previously. Most of the other factors that we found associated with lifetime suicidal ideation in the univariate and multivariate analyses have previously been reported in other studies about suicidal ideation in China; including female gender,[11,12]increasing age,[13]mood disorder,[14]other mental disorders,[15]and self reports of poor physical or mental health.[12,16]

There is one factor that did not show the expected relationship to suicidal ideation. Ningxia has undergone major changes over the last decade, many of which have resulted in the migration of residents from one community to another to make way for major construction projects or as part of government relocation programs. Indeed, over 30% of the study sample had experienced internal migration within the Province.Migration often results in major economic and social changes for individuals and families, so individuals usually experience high levels of psychological stress during the process of social assimilation to the new environment.[17]One would, therefore, expect increasedlevels of suicidal ideation in individuals who have experienced migration, but our study did not find any relationship between migration and self-reports of lifetime suicidal ideation. One possible explanation for this unexpected finding is that the Ningxia provincial government provided substantial financial and other types of support to individuals and communities that had to migrate from one part of the province to another.According to Heikkinen and colleagues,[18]community members that receive adequate social support cope better with negative life events and are less likely to have depression or anxiety; so strong social support may be a protective factor that can mitigate the negative psychological consequences of migration.

Table 2. Unconditional stepwise logistic regression results of factors associated with lifetime suicidal ideation in all respondents, in Hui ethnicity respondents, and Han ethnicity respondentsa

The higher age-adjusted rates of lifetime suicidal ideation, planning and attempt in the largely Muslim Hui ethnic group compared to the corresponding rates in the Han ethnic respondents is not consistent with the many reports from other countries which find that Muslims have much lower rates of suicidal behavior than individuals with other religious faiths, a finding that is usually attributed to Islam’s strong disapproval of suicide.[19]There are two possible explanations for this difference. Cultural assimilation of minority social culture (including religion) into the mainstream Han culture as China develops economically may reduce preexisting differences between ethnic groups in suicide rates and in the willingness to report suicidal ideation.Alternatively, the ‘true’ rates may be similar across ethnic and religious divides, but the reporting of suicidal behavior and ideation is more heavily suppressed in locations or communities where suicide is illegal or more heavily stigmatized than in China (where suicide is only moderately stigmatized and not illegal). Some studies from other non-Muslim countries[20]have also found that belief in Islam is not associated with lower rates of self-reported suicidal ideation. And a related study in Israel[21]that compared five years of suicide registry data with findings from national community surveys found that, unlike in other groups, the self reported suicidal behaviors in Muslim respondents were much higher than the rates of suicidal behaviors in Muslims identified from the registry data; this suggests that the proportion of suicides and suicide attempts that are not captured in standard registry systems is higher in Muslim community members than in other types of community members.

4.2 Limitations

Despite the relatively large sample, the numbers of respondents who reported suicidal ideation, suicidal plans and suicide attempts in the year prior to the survey were too small to justify comparisons between different groups of respondents. Thus we were required to use self-reported lifetime suicidal ideation as the main indicator variable in our analysis. There are several problems with this approach. The focus on lifetime occurrence introduced increased problems of recall bias and, thus, increased the likelihood of significant underestimation of the estimated prevalence of suicidal ideation. Using suicidal ideation as a proxy for suicidal behavior is problematic because many individuals who do not report suicidal ideation subsequently have suicidal behavior and many who do report suicidal ideation do not subsequently have suicidal behavior.More importantly, using lifetime suicidal ideation as the outcome of interest made it impossible to clarify the cause-effect relationship between this outcome and the independent ‘predictor’ variables, many of which assessed the status of the respondent in the year prior to the survey (which may have occurred after the occurrence of suicidal ideation). Thus, like in many other studies about suicidal ideation, the variables we found associated with self-reported lifetime suicidal ideation need to be confirmed in prospective studies (which would clarify the time relationship). Even larger studies that focus on suicide attempts are needed to determine whether or not the factors that predict suicidal ideation also predict suicide attempts and, ultimately, death by suicide.

Other limitations of the study included potential recall bias in assessment of some of the indicator variables (e.g., self-report disturbed sleep over the prior year, episodes of chronic pain, history of diabetes and hypertension, etc.), misclassification of religious status of some respondents by equating Hui ethnicity with Muslim religious practices (most, but not all, Hui are practicing Muslims), problems associated with administering a Mandarin-based survey to some Hui respondents who do not speak Mandarin (some, but not all, of the medical-student interviewers could speak the local language), and cultural differences in the willingness of respondents to reveal what they consider to be sensitive personal information.

4.3 Implications

This study surveyed a large, representative sample of community-living adults from Ningxia Province in northwestern China, an underdeveloped province that has a large Muslim minority group – persons of Hui ethnicity. Despite frequent reports of lower rates of suicidal behavior in individuals who practice Islam in other countries, we found a higher age-adjusted prevalence of self-reported lifetime suicidal ideation,suicide planning and suicide attempt in predominantly Muslim Hui ethnicity respondents than in predominantly atheist Han ethnicity respondents. This difference disappeared after controlling for gender, mental illness,and other factors in the multivariate logistic regression analysis. There were some relatively minor differences in the factors associated with suicidal ideation in the two ethnic groups, but the similarities were more important than the differences. Thus religious beliefs and practices may not be the main reason for the very low reported prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicidal behaviors in some Islamic countries. Cultural sensitivity,including awareness of local religious belief systems, is an important component of developing and effectively implementing any suicide prevention strategy, but the primary components of the interventions –identification of high-risk individuals, provision of high quality mental health services, reduction of substance abuse problems, restriction of means, and so forth –will remain the same regardless of the ethnicity or the religious faith of the target population.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest related to this manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by funds from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81060242)and the China Medical Board (CMB) of America (No.2011-063).

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Li Tian from the Ningxia Provincial Bureau of Health and Yi Yang from the Ningxia Center of Disease Control for their cooperation and support in the survey process. Professor Yueqin Huang from the Mental Health Research Center of Beijing University provided important suggestions in study design and implementation. Professor Michael R.Phillips provided constructive feedback in the writing and data analysis.

1. Li LM. Progress in epidemiology. 10th ed. Beijing: Beijing medical university publishing house; 2002. (in Chinese)

2. Rasic D, Kisley S, Langille DB. Protective associations of importance of religion and frequency of service attendance with depression risk, suicidal behaviors and substance use in adolescents in Nova Scotia, Canada. J Affect Disord 2011;132(3): 389-395.

3. Rasic D, Robinson JA, Bolton J, Bienvenu OJ, Sareen J.Longitudinal relationships of religious worship attendance and spirituality with major depression, anxiety disorders,and suicidal ideation and attempts: Findings from the Baltimore epidemiologic catchment area study. J Psychiatr Res 2011; 45(6): 848-854.

4. Karam EG, Hajjar RV, Salamoun MM. Suicidality in the Arab world part I: community studies. Arab J of Psychiatry 2007;18(2): 99–107.

5. World Health Organization [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013 [updated 2012; cited 2013 Oct 26].Suicide prevention and special programs. Available from:http://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/suicide/country_reports/en/index.html.

6. Singh K. Suicide among immigrants to Canada from the Indian subcontinent. Can J Psychiatry 2002; 47(5): 487-492.

7. Ningxia Provincial Bureau of Statistics. Ningxia statistical yearbook. Beijing: China Statistics Press; 2011.

8. Kish L. A procedure for objective respondent selection within the household. J Am Stat Assoc 1949, 44 (247): 380–387.

9. Kessler RC, Ustün TB. The World Mental Health (WMH)Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization(WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI).Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2005; 13(2): 93-121.

10. Ahmad OB, Boschi-Pinto C, Lopes AD, Murray CJL, Lozano R, Inoue M. Age Standardization of Rates: A New WHO Standard. GPE Discussion Paper Series No. 31 [Internet].Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001 [cited 2013 Oct 26]. Available from: www.who.int/healthinfo/paper31.pdf

11. Wang ZQ, Li XY, An J, Dong YS, Li KJ. The prevalence and risk factors of suicidal ideation among rural residents in Shandong province. Chinese Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases 2011; 37(4): 226-228. (in Chinese)

12. Feng SS, Xiao SY, Zhou L, Tang Y, Fu ZH. Risk factors of suicidal ideation in a rural community sample of Hunan. Chinese Mental Health Journal 2006; 20(5): 326-329. (in Chinese)

13. Ma X, Xiang YT, Cai ZJ. Life time prevalence of suicidal ideation, suicide plans and attempts in rural and urban regions of Beijing, China. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 2009; 43(2):158–166.

14. Yin BC, Law CK, Chan B, Liu KY, Yip PS. Suicidal ideation and suicidal attempts in a population-based study of Chinese people: Risk attributable to hopelessness, depression, and social factors. J Affect Disord 2006; 90(2-3): 193–199.

15. Hou JL, Qin XX, Li HY, Chen W, Tan SY, Jia XJ, et al.Characteristics of mental disorders and strength of suicidal ideation in suicide attempters in general hospitals. Chinese Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases 2010; 36(6): 359-363. (in Chinese)

16. Sun ML, Ye DQ, Fan YG, Pan FM. A correlation study on quality of life and suicidal ideation among rural females.Chinese Journal of Disease Control and Prevention 2007;11(2): 186-188. (in Chinese)

17. Wong DF, Song HX. The Resilience of Migrant Workers in Shanghai China: the Roles of Migration Stress and Meaning of Migration. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2008; 54(2): 131-143.

18. Heikkinen M, Aro H, Lönnqvist J. Recent life events, social support and suicide. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 1994:89(377): 65-72.

19. Li XY, Philips M, Yang SJ, Wang ZQ, Zhang YP, Lee S.Relationship of suicide acceptability to self-reports of suicidal ideation and behavior. Chinese Mental Health Journal 2009;23(10): 734-739. (in Chinese)

20. Shah A, Chandia M. The relationship between suicide and Islam: a cross-national study. J Inj Violence Res 2010; 2(2):93-97.

21. Gal G, Goldberger N, Kabaha A, Haklai Z, Geraisy N, Gross R, Levav I. Suicidal behavior among Muslim Arabs in Israel.Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol, 2012, 47(1): 11-17.

中国宁夏成人自杀意念的发生率和相关因素

王志忠1,秦英1,张毓洪1,张波2*,李林1,李涛1,丁莉1

1宁夏医科大学公共卫生学院流行病与卫生统计学系 宁夏银川

2宁夏卫生厅疾病控制处 宁夏银川

目的:比较中国宁夏回族自治区回族和汉族的自杀意念,自杀计划和自杀未遂的发生率及危险因素。方法采用概率比例规模(PPS)抽样方法,以村(居)委会为初级抽样单位,抽取城乡18岁以上的居民5880人。采用复合型国际诊断交谈表-计算机辅助中文版入户进行面对面访谈。采用逻辑回归分析自我报告的自杀意念的危险因素。结果共有4789 (81.4%)完成访谈。自杀意念,自杀计划和自杀未遂的发生率分别为5.30%(95%CI=4.66-5.93%),1.52% (95%CI=1.17-1.86%),和 0.77% (95%CI=0.52-1.02%)。以穆斯林为主的回族组(n=1955)自杀意念和自杀计划的年龄标准化率显著高于以无神论为主的汉族组(n=2834);回族的自杀未遂发生率仅仅具有较高的趋势(p=0.200)。与自杀意念相关的独立因素有女性(OR=2.07),离婚或寡居(OR=2.02),农村人口(OR=1.95),过去一年有心境障碍(OR=1.96),过去一年有其他精神障碍(OR=2.99),以及自述过去一年身体健康欠佳(OR=2.21)。通过这些因素的调整后,种族并没有与自杀意念独立相关,但是族裔群体的分层分析显示回族和汉族受访者的自杀意念相关因素的一些差异。结论与以往研究相比,我们发现自杀意念在宁夏穆斯林族组比非穆斯林族组常见,但是经过性别、精神障碍以及其他因素的校正后的多因素分析,这种差异就不存在了。

Aim:Compare the prevalence and associated factors of lifetime suicidal ideation, plans and attempts in the Hui and Han ethnic groups in the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region of China.Methods:Using a probability proportionate to size sampling method and villages (in rural areas) or neighborhoods (in urban areas) as primary sampling units, 5880 residents aged 18 and over were sampled.Face-to-face interviews were conducted using a computer-administered Chinese version of the World Health Organization’s Composite International Diagnostic Interview. Factors associated with self-reported lifetime suicidal ideation were identified using logistic regression models.Results:Of the 4789 (81.4%) persons who completed the survey, the lifetime prevalence of suicidal ideation,suicidal plans and suicide attempts were 5.30% (95% confidence interval [CI]=4.66-5.93%), 1.52% (CI=1.17-1.86%), and 0.77% (CI=0.52-1.02%), respectively. The age standardized rate of lifetime suicidal ideation and lifetime suicidal planning were significantly higher in the largely Muslim Hui ethnic group (n=1955) than in the largely atheist Han ethnic group (n=2834); the lifetime prevalence of suicide attempt was also higher in the Hui group, but only at the trend level (p=0.20). Factors independently associated with lifetime suicidal ideation were female gender (odds ratio [OR]=2.07), being divorced or widowed (OR=2.02), rural residence (OR=1.95),mood disorder in the prior year (OR=1.96), other mental disorder in the prior year (OR=2.99), and selfreported poor physical health in the prior year (OR=2.21). After adjustment for these factors, ethnicity was not independently associated with lifetime suicidal ideation, but stratified analyses by ethnic group found some differences in the factors associated with lifetime suicidal ideation between Hui and Han respondents.Conclusions:Contrary to previous studies, we found that lifetime suicidal ideation was more common in a Muslim ethnic group than in a non-Muslim ethnic group of Ningxia, but this difference did not persist in the multivariate analysis after adjusting for gender, mental disorders and other factors.

10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2013.05.004

1Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Ningxia Medical University, Yinchuan, China

2Department of Disease Control and Prevention, Ningxia Provincial Bureau of Health, Yinchuan, China

*correspondence: wzhzh_lion@126.com

(received: 2013-03-28, accepted: 2013-08-10)

Zhizhong Wang graduated with a bachelor’s degree in preventive medicine from Ningxia Medical School in 2002 and received his PhD in epidemiology and biostatistics from the Fourth Military Medical University in 2009. Since 2008, he has been working as a researcher in the Department of Epidemiology and Statistics in Ningxia Medical University, where he has been an Associate Professor since 2011. His main research interests are on mental health issues and mental health services for ethnic minorities in China.

*通讯作者: wzhzh_lion@126.com

- 上海精神医学的其它文章

- From pilot studies to confirmatory studies

- Case report of adjunctive use of olanzapine with an antidepressant to treat sleep paralysis

- rTMS in the management of auditory hallucinations in patients with schizophrenia

- The multifaceted question of the prescription of antidepressants during pregnancy

- Use of antidepressants during pregnancy: a better choice for some

- Depressive symptoms among the visually disabled in Wuhan:an epidemiological survey