ONE SHARK AT A TIME

BY K AI TL I N S OL I M I NE

ONE SHARK AT A TIME

BY K AI TL I N S OL I M I NE

China changes its tune on these monsters of the deep

人们慢慢意识到,鱼翅汤并不是婚宴酒席上的“面子”和“好意头”,而是残忍的杀戮。拒绝鱼翅,我们可以!

If you’ve been invited to a formal Chinese banquet or wedding in the past few decades, it’s likely you were served a bowl of soup. Swimming within that bowl of soup may have been translucent strands: chewy in texture, thick like vermicelli and fairly innocuous in taste. If you lifted your spoon and ate a bite, you most likely had a taste of shark fin soup (鱼翅汤 yúchìtāng).

You’re not alone, though. Shark fin soup is commonly served at Chinese weddings and banquets as a delicacy and a way of “giving face”(给面子 gěi miànzi), or showing respect to honored guests. In China, nearly everyone who has attended such an event has been served shark fin soup. AsLiang Xueni, a student at Shenzhen University and volunteer for the Chinese NGO Zero Shark Fin (中国零鱼翅 Zhōngguó Líng Yúchì), says, “My parents would tell me:‘You must eat these good things!’ Only later did I realize what I was eating, and I wondered why people need[ed] to eat this creature.”

Incidentally, many Chinese who eat shark fin soup do not even know what it is. The Chinese translation for shark fin is literally “fish wing” (鱼翅), so it is not immediately clear to diners that the stringy tendrils are actually from harvested sharks. Originally inherited from traditionally conservative Hong Kong society, the now-ubiquitous “celebration soup” has decidedly murky origins. Although shark fin is widely considered one of the “Big Four” (abalone, sea cucumber, shark fin and fish maw), a set of dishes served at Chinese celebrations to represent prosperity and health, there is disagreement regarding when shark fin soup was first served. Some sources cite a Song Dynasty (960-1279) emperor as the earliest consumer; others reference Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) emperors. In both cases, the story goes that shark fin soup was once coveted for its rarity, an irony given the fact that shark fin consumption has increased alongside the number of shark species close to extinction. As many as one-third of open ocean shark species are currently threatened with extinction, some experiencing a 99 percent population decline.

Hundreds of shark fins are left to dry in the sun

AT STAKE IS A TOTAL COLLAPSE OF THE FOOD CHAIN

Gelatinous strings of cartilage that make up shark fin soup

CULTURAL FIN-TEREST

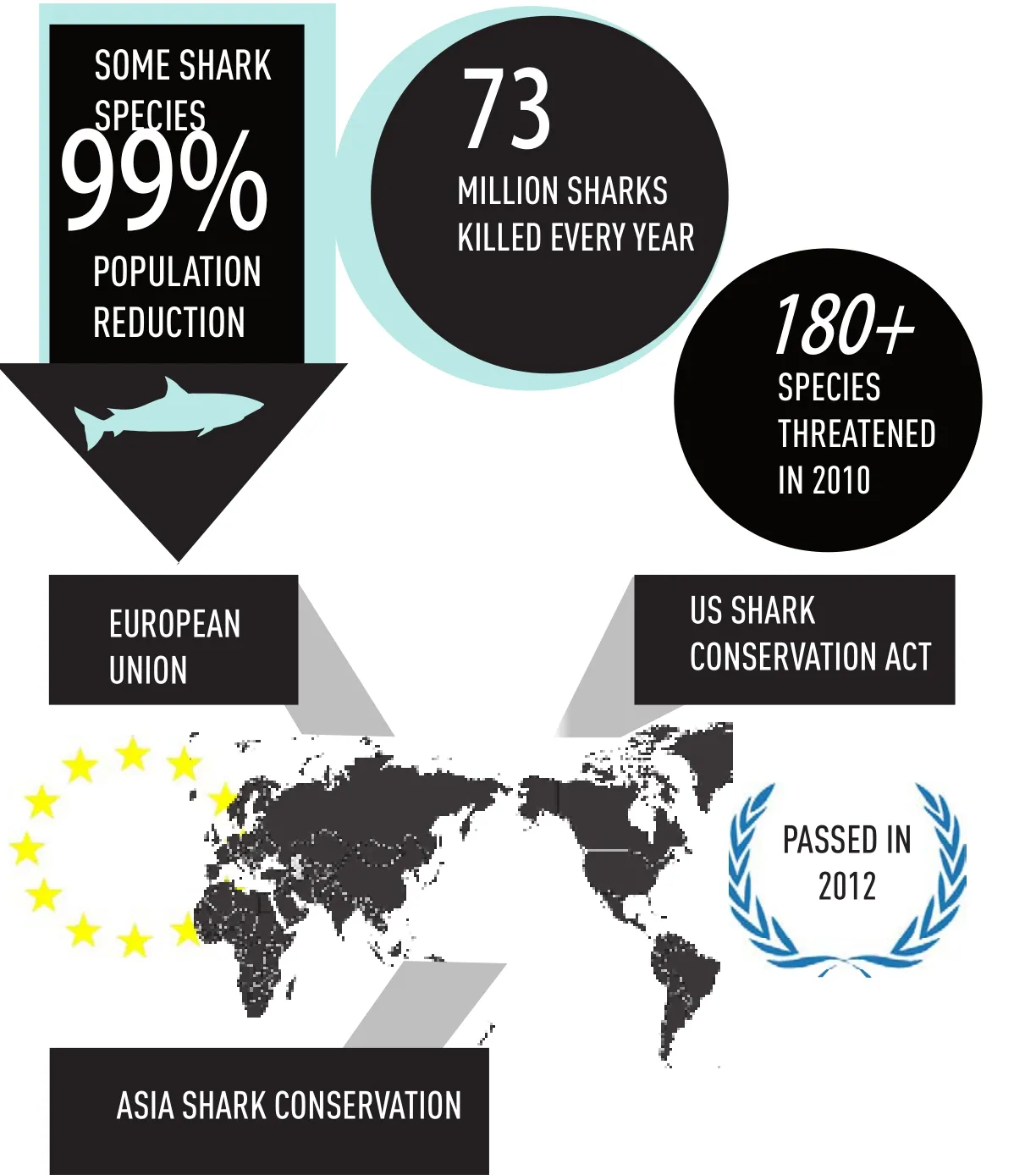

China’s recent economic boom has caused a substantial increase in the demand for the delicacy as a way of showing wealth and status. According to a study published by Shelley C. Clarke in 2006, the shark fin trade (which includes components for soup as well as medicinal remedies) kills upwards of 73 million sharks per year. While only 15 shark species were considered threatened in 1996, more than 180 species were in danger as of 2010. At stake is a total collapse of the food chain due to the fact that sharks are apex predators and are critical to the health of ecosystems such as coral reefs. To further complicate the situation, recovery of the existing shark population is disastrously slow because of their lower reproductive rates.

Recently, a widespread international movement has addressed the overfishing of the world’s most feared predator by imposing shark fin bans. These include the US Shark Conservation Act passed in 2012 as well as bans on shark fin products in California, Hawaii, Washington and Oregon. The European Union is considering a ban that would forbid shark finning in EU waters and by all EU-registered vessels.

SHARK CONSERVATION IN THE SPOTLIGHT

Around Asia, the tide has also been turning in favor of shark conservationists. Major grocers in Singapore (including Cold Storage, FairPrice, and Carrefour) have banned shark fin products from their shelves. Cathay Pacific Airlines banned the transportation of shark fin products on all its flights, and even Hong Kong Disneyland has removed shark fin soup from its banquet menus.

On an individual level, many Chinese who have eaten shark fin soup in the past have now fully changed their opinions about the consumption of shark fin due to a new understanding of the environmental ramifications of the shark fin trade. Because Hong Kong accounts for roughly 50 percent of global imports of shark fin annually (with nearly 40 percent of that coming from 14 shark species listed in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species), Bertha Lo, program director of the Hong Kong Shark Foundation, notes that Hong Kong has a special opportunity to make a change to a global problem.

Hong Kong native Clement Yui-Wah Lee, who now resides in the US, agrees. In 2010, he started a Facebook group “Cut Gift Money for Shark Fin Banquets” that quickly went viral, drawing media coverage from CNN and Hong Kong’s The Standard. Lee says he was searching for an innovative method to send a message to wedding hosts that guests are increasingly unimpressed by shark fin soup but still feel pressured to eat it, despite their qualms.

“REMEMBER, WHEN THE BUYING STOPS, THE KILLING CAN TOO.”

On the Mainland, China’s netizens have also been increasingly instrumental in conservation projects in China, notably the anti-shark fin movement. Understanding the power of social media, Jim Zhang, Managing Director of Greater China and Northeast Asia at The Nature Conservancy and a former tech entrepreneur, launched a Weibo campaign to spread his environmental messages. He quickly gained over half a million followers. The campaign even convinced the Hong Kong Jockey Club’s Beijing clubhouse to remove shark fin soup from its menus. Similarly, Jack Ma (马云), founder of China’s popular e-commerce site Alibaba. com, publicly forswore shark fin soup—a portion of the Alibaba Group’s annual revenue is now set aside for environmental protection.

Finally, the National People’s Congress of China, listening to concerned Chinese citizens who filed a petition against shark fin products, followed suit. In July 2012, the State Council of China announced that it would publish regulations within the next three years, aimed at forbidding shark fin to be served in official banquets.

NGOs have also pressured a number of hotels in China to change their ways. As a result, the Peninsula and Shangri-La Hotel chains have removed all shark fin products from their menus. Clement Lee notes, however, that some interests such as shark fin traders and restaurant owners, like to paint a picture that being“anti-shark fin is racist (anti-Chinese),” but he says this is absolutely false. The number of Chinese Mainland and Hong Kong activists easily prove the fallibility of thisargument.

Even NBA All-Star Yao Ming (姚明), a vocal antishark fin activist, echoes the sentiment that anyone consuming or purchasing shark fin is implicated in the near-extinction of the species. In a public service announcement video produced by Shark Savers and Wild Aid, Yao Ming emphatically says, “Remember, when the buying stops, the killing can too.” (没有买卖,就没有杀戮。Méiyǒu mǎimai, jiù méiyǒu shālù.)

CHALLENGES AND OBSTACLES

In 2009, Zero Shark Fin, a Chinese NGO, was founded in order to increase public awareness of the threats to global shark populations. Zero Shark Fin’s campaigns include awarding restaurants who do not serve shark fin a “Shark Fin Free” label and asking citizens to sign a pledge that they will not eat shark fin soup (an activity similarly employed by international organizations like Wild Aid and Shark Savers).

Despite this, organizations such as Zero Shark Fin and their volunteers cite that one of the biggest challenges to the cause is overturning existing societal notions. The idea of “giving face” in China has deep roots. Particularly for older generations, the desire to show wedding and banquet guests that they are respected is a practice intrinsically tied to serving delicacies such as shark fin soup. But as Zero Shark Fin volunteer Liang Xueni asks of her fellow Chinese citizens: “What truly is ‘face’? What is ‘auspicious’ (好意头 hǎoyìto)?” Her questions point to a growing sense that the idea of showing face means much more than mere prosperity and riches. The question remains as to how best to educate the public about the consequences of their consumption of products like shark fin soup.

Wang Xue, director of Zero Shark Fin, notes that her argument against shark fin soup is three fold: “First, not all cultural practices are inherited; second, there is no nutritional value in shark fin; and finally, there are even some proven health dangers to ingesting the product.” Wang’s last point, on the health dangers of shark fin, is one that deters many would-be shark fin soup consumers. Sharks, (like tuna and other large fish), are apex predators in the food chain that live long lives, makes them extremely high in mercury. This can be dangerous for humans, especially children, the elderly, and pregnant women.

In a Weibo discussion on the issue, The Nature Conservancy’s Zhang notes that China’s international image could be greatly enhanced if the nation took a stand on environmental issues, including prohibiting shark fin consumption and protecting the oceans. This“soft power” could be of great political and cultural benefit to China in the long term.

Anti-shark fin activists and environmental conservationists in China and abroad may likewise take heart in young volunteer Liang Xueni’s words: “I believe that within our hearts lies a seed of goodness: perhaps this seed is still in its infancy—perhaps it is still dormant—however, we must nurture it to maturity. Only then can we prevent more harm to the sharks of the world.”

Chinese basketball star Yao Ming launches the global shark conservation campaign with business tycoon Richard Branson