Biliary-colonic fistula caused by cholecystectomy bile duct injury

Miami, USA

Biliary-colonic fistula caused by cholecystectomy bile duct injury

Francisco Igor B Macedo, Victor J Casillas, James S Davis, Joe U Levi and Danny Sleeman

Miami, USA

Biliary-colonic fistula is a rare complication after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. We present a case of postcholecystectomy iatrogenic biliary injury that resulted in a fistula between the common hepatic duct and large bowel. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography provided good visualization of injury even with concurrent normal level of alkaline phosphatase. Radiologic findings and surgical management of this condition are discussed in detail.

cholecystectomy; magnetic resonance imaging; biliary tract disease

Introduction

Iatrogenic biliary duct injury is a serious and potentially life-threatening complication after laparoscopic cholecystectomy, with an incidence of 0-1.2%.[1]In such injuries, less than 1% leads to internal biliary fistulae, most of which are choledochoduodenal fistula.[2,3]Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) have traditionally been performed preoperatively to define biliary anatomy. However, these procedures are invasive and potentially causative for serious complications.[4]In the present case, we used magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) as the first diagnostic tool to assess the biliary tree of a suspected iatrogenic injury. We found that MRCP can be used as the best radiologic approach to assess the lesion since it is not only accurate in detecting injury site but also superior in delineating proximal ductal anatomy in complete obstruction of the bile duct.[5]

The present case had a biliary-colonic fistula caused by iatrogenic biliary injury following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. To our knowledge, less than five similar cases have been reported worldwide.[6-8]This report aimed to highlight different radiologic approaches, MRCP in particular in the assessment of the lesion, and to discuss potential surgical options.

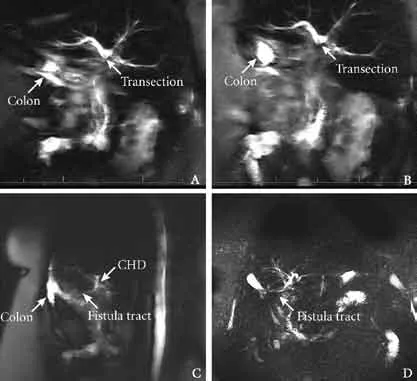

Clinical images

A 58-year-old woman underwent a laparoscopic cholecystectomy, during which a common bile duct injury was suspected. Postoperatively, the patient developed nausea and vomiting with increased Jackson-Pratt (JP) drain output. She was thereafter transferred to our institution for subsequent management. At presentation, she was asymptomatic, and had normal white blood cell count and level of alkaline phosphatase (8.9×103/mL and 90 U/L, respectively). MRCP revealed a fistula between the biliary tree and the enteric tract (Fig. 1). PTC was attempted but failed to visualize the biliary tract. She recovered from her initial presentation and was discharged home. She was readmitted for redo PTC, showing a fistula communicating the biliary tree. Colon and fecal content was seen in the transhepatic catheter output and balloonplasty was performed to dilate fistulous communication and allow continuous biliary drainage to the colon (Fig. 2). She underwent elective biliary reconstruction one month later. Intraoperatively, the common hepatic duct was completely obliterated distal to the confluence of right and left bile ducts. The fistula was visualized and closed with a thoraco-abdominal stapler. The confluence of the biliary ducts was anastomosed to a loop of the jejunum, which was tied to the right abdominal wall in a Hutson-Russell fashion.[9]The postoperative course wasuneventful, and she was discharged from the hospital on postoperative day 10 after cholangiography confirmed the patency of the anastomosis.

Fig. 1.MRCP showing complete transection distal to the confluence of right and left bile ducts (A,B). MRCP demonstrates fistula tract between the common hepatic duct and colon (C,D). MRCP: magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography; CHD: common hepatic duct.

Fig. 2.PTC demonstrates contrast filling biliary tree and large bowel. Multiple clips are visualized distal to injury (A,B). Dilatation of the biliary tree with non-visualized common bile duct (C). Balloonplasty of the fistulous tract of the biliary tree to the large bowel is performed with placement of an 8-Fr external drainage catheter. PTC: percutaneous trans-hepatic cholangiography.

Discussion

Biliary enteric fistulas are rare complications usually observed in patients with long-standing biliary stone disease, duodenal ulcer, common bile duct tumors or after sustained duodenal blunt trauma.[10]Postoperative biliary fistulas have been described after liver transplantation, hepaticojejunostomy and, rarely, after iatrogenic injury following cholecystectomy. Of these fistulas, choledochoduodenal fistula is the most common type.[7]

Although biliary-colonic fistula is not common, it may occur spontaneously secondary to choledocholithiasis and colonic diverticulitis.[11,12]It is an unusual complication after cholecystectomy, and only a handful of cases have been reported previously. Its exact mechanism may involve the formation of an internal biliary collection secondary to biliary wall erosion and/ or tear and distal obstruction that eventually erodes into the colon, forming the fistula.[6]

The clinical signs of the disease usually include nausea, vomiting, right upper quadrant pain, associated with or without peritoneal signs, pruritus or sepsis. Increased levels of alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin are remarkable. In this patient, the level of alkaline phosphatase was surprisingly normal at presentation, making the differential diagnosis more difficult. Initially, the patient presented with nausea, vomiting and increased JP drain output. All these signs subsided, but she remained asymptomatic with a low drain output. This finding was consistent with the previously reported cases, in which the postoperative course was marked by higher than normal biliary drainage that spontaneously resolved. In such cases, the diagnosis of biliary-colonic fistula should be considered.

Current diagnostic tools for biliary-colonic fistula include ultrasound, computed tomography, MRCP, cholescintigraphy, PTC and ERCP. Although ERCP has been advocated as the best tool as it has both diagnostic and therapeutic potential, it is invasive and associated with complications. Recent studies have proposed MRCP as the best tool to assess biliary injury, since it has similar accuracy as ERCP to define the site of injury. However, it is superior in delineating proximal ductal anatomy in complete obstruction of the bile duct.[5,13]MRCP also can be used in successful biliary reconstruction.[14]However, its cost-effectiveness remains unclear and further studies are needed. We found that in complete distal transection of the common bile duct or in cases with distal obstruction due to inadvertent clipping, ERCP is limited due to inability to visualize proximal bile ducts. Hence, further characterization of the proximal biliary tree is necessarywith either MRCP or PTC. In this study, MRCP was used as the first diagnostic tool in early detecting a biliary colonic fistula in an asymptomatic patient with a normal level of alkaline phosphatase.

In patients with biliary-colonic fistula, biliary reconstruction is required with hepaticojejunostomy with Hutson-Russell procedure; however, Roux-en-Y jejunal limb may also be used.[15]Management with percutaneous or endoscopic stent across a strictured biliary-colonic fistula is not recommended and may be associated with a high morbidity. Intraoperative factors associated with unfavorable outcomes include incomplete excision of the scared duct, failure to eradicate subhepatic infection and two layer anastomosis.[6,14]Referral to a tertiary center with an experienced biliary surgeon is associated with improved outcomes.[16]

In conclusion, biliary-colonic fistula is a rare complication after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Timely and adequate recognition is crucial to minimize significant morbidity. MRCP has shown excellent results with good visualization of an early biliary-colonic fistula, and is essential for definition of surgical plan with satisfactory long-term outcomes.

Contributors:MFIB drafted the manuscript. SD revised and approved the manuscript. SD is the guarantor.

Funding:None.

Ethical approval:This study has been approved by our hospital.

Competing interest:No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Richardson MC, Bell G, Fullarton GM. Incidence and nature of bile duct injuries following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: an audit of 5913 cases. West of Scotland Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy Audit Group. Br J Surg 1996;83:1356-1360.

2 Hunt DR, Blumgart LH. Iatrogenic choledochoduodenal fistula: an unsuspected cause of post-cholecystectomy symptoms. Br J Surg 1980;67:10-13.

3 Sato T, Denno R, Yuyama Y, Matsuura T, Kanisawa Y, Hirata K. Unusual complications caused by endo-clip migration following a laparoscopic cholecystectomy: report of a case. Surg Today 1994;24:360-362.

4 Fulcher AS, Turner MA, Capps GW. MR cholangiography: technical advances and clinical applications. Radiographics 1999;19:25-44.

5 Khalid TR, Casillas VJ, Montalvo BM, Centeno R, Levi JU. Using MR cholangiopancreatography to evaluate iatrogenic bile duct injury. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2001;177:1347-1352.

6 Munene G, Graham JA, Holt RW, Johnson LB, Marshall HP Jr. Biliary-colonic fistula: a case report and literature review. Am Surg 2006;72:347-350.

7 Asbun HJ, Rossi RL, Lowell JA, Munson JL. Bile duct injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: mechanism of injury, prevention, and management. World J Surg 1993;17:547-552.

8 Coakley FV, Schwartz LH, Blumgart LH, Fong Y, Jarnagin WR, Panicek DM. Complex postcholecystectomy biliary disorders: preliminary experience with evaluation by means of breath-hold MR cholangiography. Radiology 1998;209:141-146.

9 Hutson DG, Russell E, Schiff E, Levi JJ, Jeffers L, Zeppa R. Balloon dilatation of biliary strictures through a choledochojejuno-cutaneous fistula. Ann Surg 1984;199:637-647.

10 Lin CT, Hsu KF, Yu JC, Chu HC, Hsieh CB, Fu CY, et al. Choledochoduodenal fistula caused by cholangiocarcinoma of the distal common bile duct. Endoscopy 2009;41:E319-320.

11 Güitrón-Cantú A, Adalid-Martínez R, Barinagarrementeria-Aldatz R, Carrillo-Maciel V, Gutiérrez-Bermúdez JA, Meza-Mata E. Choledochocolonic fistula secondary to primary choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc 2001;54:227.

12 Benson AJ, Reinschmidt J, Billingsley JL, Timmons JH, Parish GH. Biliary-colonic fistula diagnosed via hepatobiliary scintigraphy. Clin Nucl Med 2001;26:150-151.

13 Ragozzino A, De Ritis R, Mosca A, Iaccarino V, Imbriaco M. Value of MR cholangiography in patients with iatrogenic bile duct injury after cholecystectomy. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2004;183:1567-1572.

14 Stewart L, Way LW. Bile duct injuries during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Factors that influence the results of treatment. Arch Surg 1995;130:1123-1129.

15 Schmidt SC, Settmacher U, Langrehr JM, Neuhaus P. Management and outcome of patients with combined bile duct and hepatic arterial injuries after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surgery 2004;135:613-618.

16 de Reuver PR, Grossmann I, Busch OR, Obertop H, van Gulik TM, Gouma DJ. Referral pattern and timing of repair are risk factors for complications after reconstructive surgery for bile duct injury. Ann Surg 2007;245:763-770.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2013;12:443-445)

June 4, 2012

Accepted after revision December 10, 2012

Author Affiliations: Dewitt Daughtry Family Department of Surgery (Macedo FIB, Davis JS, Levi JU and Sleeman D) and Department of Radiology (Casillas VJ), University of Miami Miller School of Medicine and Ryder Trauma Center/Jackson Memorial Hospital, Miami, Florida, USA

Danny Sleeman, MD, Jackson Memorial Hospital 1611 N. W. 12th Avenue, Miami, Florida, 33139, USA (Email: dsleeman@ med.miami.edu)

© 2013, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

10.1016/S1499-3872(13)60070-3

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2013年4期

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2013年4期

- Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Hepatic abscess associated with Salmonella serotype B in a chronic alcoholic patient

- A new veno-venous bypass type for ex-vivo liver resection in dogs

- Effect of L-cysteine on remote organ injury in rats with severe acute pancreatitis induced by bile-pancreatic duct obstruction

- Endobiliary radiofrequency ablation for malignant biliary obstruction

- The diagnostic value of high-frequency ultrasonography in biliary atresia

- Impact of periampullary diverticula on the outcome and fluoroscopy time in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography