The History of Seals

CHINESE ancestors began engraving pictographs on tortoise shells and animal bones as early as the 14th century BC. The practice later expanded to include bronze wares and marble slabs. These impressions were the forerunners of seals, which functioned first of all as business credentials and later as designating specific government departments.

Until the unification of China by Emperor Qin Shihuang of the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BC), both official and private seals were referred to indiscriminately as 玺 xi. From that time onward, the character 玺 xi was reserved for royal seals. Those of courtiers and commoners came under the broad heading of 印 yin. Prior to and during the Han Dynasty, letters written on bamboo or wooden slips bore clay-imprinted seals whose purpose was to deter anyone but the addressee from opening the document. It was – and still is –traditional for painters and calligraphers to sign their works with personal seals in red ink or cinnabar paste.

Early seals were made of bronze, gold, silver and jade, and later of ivory, ox and rhinoceros horn, wood and crystal. Seals carved out of rare rocks became popular after the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368).

During the Tang Dynasty Wu Zetian (624-705), the only female monarch in Chinese history, changed the name of the royal seal to 宝 bao. To her mind, the pronunciation of 玺 xi was too similar to si 死 , meaning death. In later times bao and xi were either interchangeable or amalgamated in the term 宝玺 baoxi.

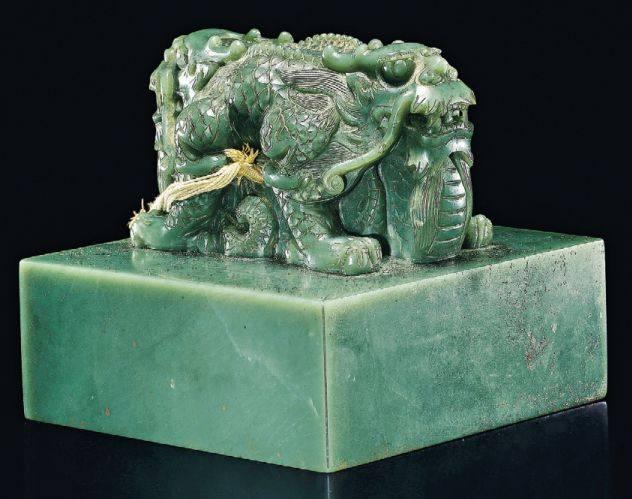

Two ancient seals were star lots at the 2013 China Guardian spring auction. One belonged to Qing Emperor Qianlong (1711-1799), the other to Qing ruler Jiaqing (1760-1820). The former, of white jade, was hammered out at RMB 66.7 million after more than a dozen bids. The latter, of green jade, sold for RMB 34.5 million.

Qianlongs seal bears the motto “unceasingly improve oneself.” Its handle consists of imposingly fashioned twin dragons. One of the “eight treasures” specifically produced to celebrate the 80th birthday of the Qing monarch, the seal was formerly in the collection of French industrialist, traveler and connoisseur Emile Guimet (1836-1918). He purchased it from Paris antique dealer Galerie Langweil in the early 20th century.

Jiaqing, the 15th son of Emperor Qianlong, inherited the throne after his fathers abdication. The green jade seal bears the characters “seal for Jiaqings royal writings,” and also has a twin dragon handle. The original yellow ribbon embellishment is well preserved, its pattern and the way it is tied complying with Qing etiquette as laid down in historical documents.

In the Qin and Han dynasties, each emperor had eight seals for different administrative purposes. This tradition continued until the reign of Tang female monarch Wu Zetian, who added one to the set. During the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) it grew to 24.

Qianlongs reign lasted 60 years, and is regarded as the heyday of the Qing Dynasty. Historical records show that he had as many as 25 seals in 1746, each representing the supreme power of state. They included one applicable to enthronement statements, one for sacrificial rituals, one for educational and cultural decrees, and one for diplomatic documents. Mostly made of jade, imperial seals were also of silver, gold and wood. The Palace Museum in Beijing houses nearly 5,000 seals originally belonging to Ming and Qing emperors and empresses.