Qiannan Prefecture–The Land That Time Forgot

By WU MEILING

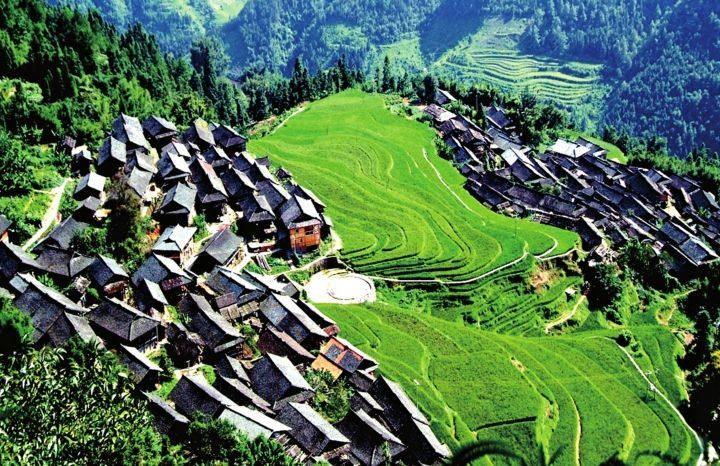

QIANNAN Bouyei and Miao Prefecture in southwestern Chinas Guizhou Province boasts dual blessings from mother nature – the uncanny beauty of karst topography and primeval forests. Its hard to say which aspect of the landscape is more arresting –the wild Avatar-esque alienness of the vertiginous peaks, or the forests, which have sustained an ecosystem brimming with life for millennia upon millennia. For tourists, the question is moot; both can be appreciated in equal measure on short trips from the prefectural capital of Duyun.

Libo, a Legacy of History

A 2005 poll by Chinese National Geography magazine voted the karst scenery in Libo, Qiannan Prefecture, the No. 8 most fascinating such formation in China. Thats quite an achievement, considering Libo is way off the beaten tourist trail, and the other top 10 placegetters are overtly commercialized.

Karst topography is the geological phenomenon created by the dissolution of one or many layers of soluble bedrock. It is named after the Kras plateau region of eastern Italy and western Slovenia(Kras is German for “barren land”). The landscape on most karst terrains is rocky and barren, with a thin layer of soil to support vegetation. In Guizhous Libo, however, the situation is very different: the soil covering the karst landscape is rich; the area is home to 20,000 hectares of primeval forestlands.

Anyone who has the chance to view this expanse of green that rolls up and down the rugged mountain surely comes away with a different perspective on life. So few people have ventured here over the course of human history that with every step, the visitor could well be the first person ever to walk across a rock surface that has been untouched for 100 million years.

The Libo region emerged out of the sea following tectonic plate movements about 200 million years ago. As the landscape continued to develop over the following millennia, biodiversity in the area grew.

Today, the flora and fauna of Libo is unique. The ecosystem of the karst area is nonetheless extremely fragile; any major natural disaster, and especially fire, would wreak havoc. Deforestation and illegal logging is also a concern. Primeval forests are especially fragile, not just in Libo but the world over. For this reason, there are few such forests – especially in karst regions – of the scale found in Libo remaining in the world

Among Libos unique flora is the Kmeria septentrionalis Dandy, a dioecious tree species that was announced extinct by international scientists back in 1933, and wild Paphiopedilum emersonii, an orchid species. All in all, the region holds 1,203 floral species including 32 genera of wild orchid. It is also home to 316 species of vertebrates and 800 species of insects. More than 170 plants and animals are under top-level national protection.

Chinese botanist Qin Renchang first discovered the Kmeria septentrionalis Dandy in neighboring Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region in 1928, though it died out there a few years later. In 1937 the international botanical community announced the species extinct. Half a century later, however, a grove of as many as 20,000 of the trees was found deep inside Libo; many towered to a height of six to seven meters. The news caused a sensation in international biological circles. Experts were over the moon about the news of the survival of these “botanic giant pandas.”

Sitting below the canopy of a towering Kmeria septentrionalis Dandy tree, I remembered a poem by the Sixth Dalai Lama, Tsangyang Gyatso:

See me or not,

I am always here,

Not gleeful, nor rueful.

Think of me or not,

My love is always here,

Never going this way or that.

The Maolan National Forest Reserve in Libo sees the four features of the karst forest brought out in spectacular display: trees surviving – and thriving – between bedrock, up through sinkholes, out of streams and in underground caverns. The 20,000 hectares of lush green on the otherwise lifeless rocky terrain stand testament to the ability of nature to thrive in seemingly impossible conditions.

The Xiaoqikong area of the reserve is the prime location to see the “woods on the water.” Normally trees cant survive in rivers, but several elements collaborate in Xiaoqikong to create exceptional circumstances. The forests in the area originally grew out of soil, before being flooded by water from underground caves of soluble rock. The calcium carbonate in the water, at high concentration, soon accumulated and formed a crust around the roots, protecting them from being “drowned.” Its almost as if the trees are wearing rubber boots.

The Wangpai Peak is home to a stretch of “funnel forest.” The funnel is a 400-meter-deep cone-shaped hollow, the walls of which are covered in dense foliage. Looking down from the top of the peak into the hollow, the depth is startling.

A peerless spectacle in the reserve is the underground forest. Its not a metaphor. In the darkness of a limestone cave, unexcitedly called “Cave 1285,” grows a sprawl of eerily warped trees whose leafless branches all stretch downward. On closer inspection one sees that the “branches” are actually the root system of aboveground woods that, astonishingly, have pierced dozens of meters of bedrock to reach the cavern below, and have continue to grow down even further.

Another charming feature of the reserve is its water system, which includes waterfalls, rock pools and rivulets both above and under ground. A standout that makes for a postcard photo is the Yuanyang (Mandarin Duck) Lake – two major lakes, four smaller ones and a number of interconnecting brooks form a dynamic maze of waterways that bulge and shrink depending on the season. They say the color of the water also changes depending on the time of day, and glimmers in up to seven different shades.

The Shui Ethnic Group

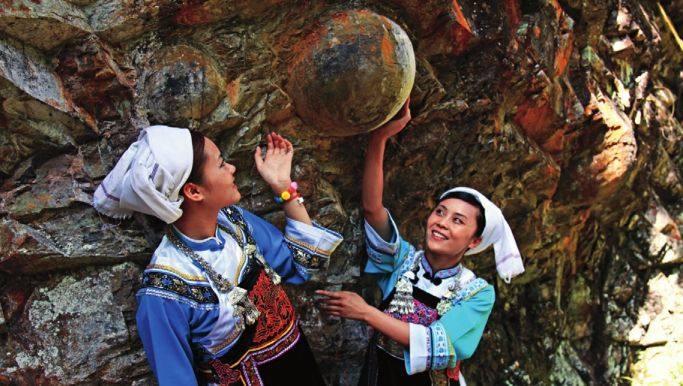

In the south of the prefecture is Sandu Shui Autonomous County, Chinas only autonomous county of Shui, an ethnic minority of 400,000. Legend says the scenery there is “as beautiful as the feather of a phoenix.” And sure enough, with Yaoren Mountain, the Dulliu River, Chandan Cliff, which “lays stone eggs”(more on that oddity below), and the“Moonlight Tree,” which shines in the evening, the county does not disappoint.

But the real treat here is meeting the locals. Fully half of all Shui live in Sandu.

The origins of the Shui people are indicated in a folk song passed down through the generations and still sung today:

In the late Shang Dynasty,

From the southern mountains we came.

With our language, the gift of our ancestors,

Home in Yelang Kingdom we claimed. Looking back to my forgotten land, I see the moon reflected in rivers grand.

The song thus tells us that the Shui are not the aboriginal inhabitants of Sandu, but migrated from another region. From where exactly did they come? Its hard to know. Popular folk legends, songs and even religious incantations all indicate that they moved from the south of China – there are many references to water and even the sea. In many Shui customs fish constitute a very important element.

Many scholars now believe that the Shui are actually one clan of the Baiyue, a collection of tribes that inhabited southern China in ancient times. But the question is yet to be conclusively settled– the Shuis written language seems to suggest they might be from the central area of China, and that they could have been an ancient Han Chinese tribe.

The Shui have their own written language. The pronunciation of the spoken tongue is very different from modern Chinese, but in some ways resembles ancient Chinese. Shui Language and the Origin of the Shui Ethnic Group, a monograph by renowned sociologist Professor Cen Jiawu, mentions, “The written language of the Shui is the product of an ancient area, quite possibly the Shang Dynasty (circa 1600-1100 BC). It bears close resemblance to oracle bone characters and inscriptions on ancient bronze objects.”

Indeed, the surviving 200 Shui characters are mostly pictographic, much like the oracle bone script, bronze ware inscriptions and other ancient Chinese characters. Distinguished scholar Mo Youzhi believes the Shui characters represent a language of the pre-Qin period(2100– 221 BC). In his research on the language, he found an important clue in a line that read “copying writings from bamboo slips,” which indicates that the earliest version of Shui books were written in a form common in ancient China. The finding is also in accordance with records from Shangshu, or Book of Documents, an ancient tome about the history of the pre-Qin eras, which noted that only people of the Shang Dynasty had documents and books.

In the year 221 BC, when the Qin monarchy conquered large swathes of the territory of China, the emperor sent a contingent of 500,000 soldiers to Lingnan, an area covering the whole of todays Guangdong, Guangxi, Hainan and part of neighboring provinces. The troops were led by a general named Wei Tu Sui. In the Qin period, there was no standard way to record peoples names, and a citizen was usually called after his or her demeanor or achievements. “Wei Tu Sui” literally means “Slaughterer of the Sui”; could this Sui be the “Shui” of modern times?

This history was recorded on a stone relief found in Shibanzhai Village of Sanshuiqian Town. The carvings are fluid and delicate, representing the style of the Ming Dynasty (1368 – 1644). The figures depicted in the relief wear either long robes or armor.

In the center stand three people. The central figure wears an officials hat and shows kindness on his face; on the right stands an elderly man with a long beard who is holding a stick in his left hand and, with his right, is handing fruit to a child. The child is held by a woman, standing on the left, who wears a striking headband. The three are guarded by a phalanx of soldiers who hold flags that feature a dragon. Their flag-waving has startled a flock of geese, who have soared up into the sky.

The stone relief vividly depicts a scene of migration. After Qin conquered Lingnan, the ancestor of Shui presumably went upstream along the Duliu River to a place between modern-day Guizhou and Guangxi, and settled there. In the inland, however, small ethnic groups soon assimilated into the more populous Han people. Many of their cultures disappeared. The Shui written language presumably survived thanks to the groups mountainous homeland.

Despite the Shuis official recognition, most people today still know relatively little about the ethnic groups customs and culture. For instance, the Duan Festival of the Shui, which celebrates the New Year, lasts about 49 days, making it the longest annual festival in the world. Come summertime, the Shui celebrate the Mao Festival, the worlds oldest festival for lovers. The grand Jingxia Festi- val has a history of over 1,000 years. It involves worship of the Shuis rain god and takes place once every 60 years. The Horsetail Broidery technique of the Shui is a living fossil: as its name suggests, hairs on the horsetail make part of the threads used. It was among the first cultural heritages to be officially recognized – and protected – in China.

Arriving in Sandu, we heard about reward of RMB 500,000 for the person who could solve the mystery of Chandan(Egg Laying) Cliff, which, as mentioned, is said to “lay stone eggs.”Located just nine kilometers away from the county town, the cliff is located in a typical Shui village where residents still live in stilt houses and wear traditional costumes. Once every 30 years, several stones the size of dinosaur eggs are found at the foot of the cliff. No one knows where they come from. They arent pieces that have crumbled off the cliff, nor are there any such rocks on top of the cliff. Needless to say, we didnt solve the mystery.

Pingtang County

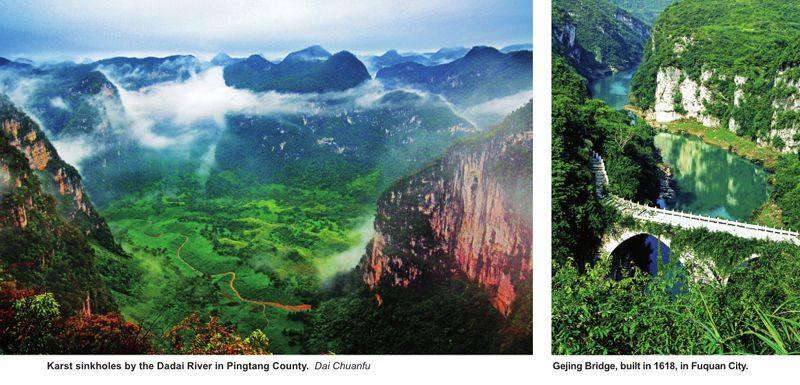

Pingtang County has karst mountain and river views to rival any other scenic spot in the autonomous prefecture. In China Pingtang has already gained a reputation as a geological marvel. It has over 100 recognized sites of sightseeing interest, including Pingzhou River, the Jiacha Scenic Area and the Longtang Scenic Area. In 2009 Pingtang was elected as one of Chinas 10 most beautiful small cities.

Oddly enough, Pingtangs renown as a spot of peculiar natural beauty is somewhat overshadowed by its reputation as a future hub for scientific research. News broke recently that an enormous radio telescope, measuring 500 meters in diameter, will be built in Dawohan, a natural basin in Pingtang. Since the mid-1990s, Chinese astronomers and their colleagues from other countries have visited the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau on many occasions to search for an ideal location for their huge telescope. They finally chose Dawohan, and the whole area is set to benefit from the influx of scientists.

The Dawohan area is home to karst landforms with natural hollows scattered among the verdant mountains. The hollows are like naturally formed shelters, which, scientists say, provide perfect conditions for the construction of the worlds largest and most sensitive single-aperture radio telescope.

Construction of the telescope is well underway. After it is completed, the powerful instruments will be turned to the sky to spy on the wonders of the universe. But there are wonders on earth as well, and some of them are right next to the telescope. Hiking around Dawohan, visitors can take in picturesque scenery of rising peaks, purple Chinese wisteria, karst caves and old, traditional villages.

There are many peculiarly shaped rocks around Pingtang County. For instance, there is one particular rock face in Cangzi Rock Valley that has cracked in a way to resemble the five Chinese characters “the Communist Party of China.” The locals call it “a letter from heaven.”

Getting to the valley where the rock is located requires hiking, but the route is lovely and dotted with creeks, waterfalls and bamboo forests. The uncanny inscribed monolith, called Hidden Words Rock, is actually at the end of the valley. It has split into two pieces, both of which are around seven to eight meters long and three meters high. Theres a gap of about a meter separating the two rocks, and the five Chinese characters are on the middle part of a fractured surface on the right-hand piece. The “writing” was actually formed naturally around 200 million years ago – when Guizhou Province was at the bottom of an ancient sea. One day, the logic goes, the huge rock rolled down from the top of an ocean peak into the valley and broke into two pieces. The fissures that make up the characters could actually be imprints of the fossils of brachiopods, according to scientific studies.

Fuquan and the Yelang Kingdom

Visiting Fuquan City, we leave the epic natural scenery behind and take a tour down history lane. Fuquan was the seat of Qieland Kingdom during the Spring and Autumn Period (770-476 BC), and was also the capital city of the ancient state of Yelang over 2,000 years ago. Plenty of historical sites have survived, and visitors today have plenty of choices.

The first site we visited in Fuquan was the ancient city wall. The citys layout and construction techniques reflect the wisdom of planners during a period of war. Standing on the city wall, visitors gain a panoramic view of Fuquan. The city itself is divided into an “inner sanctum,” the middle “water city” and the outlying suburbs.

The inner city sits high on the top of a hill and enjoys a commanding position over the whole cityscape. A river winds downhill and connects the inner and outer city sections. The outer city stretches to surround three sides of the inner city – as protection in former times. The three parts form a staircasestyle defense system. There are two stone arch bridges across the river to connect the inner and the outer city. Iron lock gates feature at the entrance to the bridges from the outer city, ostensibly to cut off the waterway and prevent sneak attacks. During the An Bangyan Rebellion against the Ming Dynasty from 1621 to 1627, Fuquan, thanks to its defenses, withstood and beat back an attack from 30,000-odd enemies with a skeleton army of a few hundred.

Six hundred years later, the citys appearance hasnt changed much. The river still flows and the four towering city gates still look magnificent – and imposing.

Within the broader Fuquan city limits lies Zhuwang, capital of the ancient Yelang Kingdom.

Over 2,100 years ago, Yelang King Zhuduo is reputed to have rhetorically posed a question to a Han imperial envoy: “Which is greater, Yelang or Han?”In the end the kings arrogance led to the states demise with the defeat of his 100,000-men army. Exactly how the Yelang faded away is something of an unsolved mystery. Today the historical ruins of the kingdom are still on display in Fuquan.

Within Zhuwang itself is a village called Yanglao. Most streets and lanes in the community are paved with blue slabstones, which at first glance appear to be very old. But there is no record proving the streets were paved when Yelang was at its prime.

Emperor Jianwen (1377-1402) of the Ming Dynasty fled to the region after a coup by his uncle, and left behind his inscription on the cliff of a lotus-shaped peak near the village. It reads “Godcarved Lotus.”

The ruins of Zhuwang City attest to a well thought-out layout and an imposing array of grand architectural achievements. The streets are in a grid layout, the major thoroughfare eight meters wide. Lanes, four meters wide, branch off from it. The Yanglao River flows past the foot of the city. A 150-meter-long, 1.5-meter-wide and 2-meter-high tunnel con- nected the fortified city with the river. It was most likely used for obtaining water during times of war. There are five beacon towers on the mountains around the Zhuwang City. The soil around the river is extremely fertile, and provided sustenance for Zhuwangs citizens. On leaving, we decided it was a great pity that this once glorious state had ceased to exist.

One spot not to miss in Fuquan is Fuquan Mountain, a holy site for Taoists located to the south of the city. Zhang Sanfeng, a legendary Chinese Taoist priest during the Ming Dynasty, lived on the mountain for eight years. Standing on the top of the Fuquan Mountain and looking down, we saw undulating slopes folding out from the banks of a nearby river. It was extremely pleasant, and no doubt a peaceful environment to come and contemplate lifes inner meaning.

Zhang Sanfeng is believed by some people to have achieved immortality. Whatever his mortal status, during his time he was a master philosopher, painter, calligrapher and poet. He was also known as an expert in medicines, Qigong (breathing exercises) and Tai Chi. In one letter to Emperor Yongle of the Ming Dynasty, he wrote:

“If you want to ask me how to achieve immortality, I would reply that there is nothing special about immortals. Mortal or otherwise, the most important thing for maintaining physical and mental health is moral cultivation, continence and keeping a peaceful mind.”

A memorial temple has been built on Fuquan Mountain to commemorate Zhangs stay here and his brilliant contributions to health and martial arts. In the temple there is stone-carved portrait of the master, which fully reflects the transcendent demeanor attested to him. For those wishing to pay tribute to the legacy of Zhang, a visit to Fuquan Mountain is a must.

Fuquan City is also home to 130-odd ancient bridges, all of which have their own special features. Among them is the One Step Bridge from the Qing Dynasty, the smallest in China. One step, and youre across it.

That one step proved to be one of my last in Qiannan Prefecture. Its a shame, because I felt Id barely scratched the surface of this fascinating pocket of China.