ITER解决最棘手难题:用钨与铍涂装反应堆内层

ITER解决最棘手难题:用钨与铍涂装反应堆内层

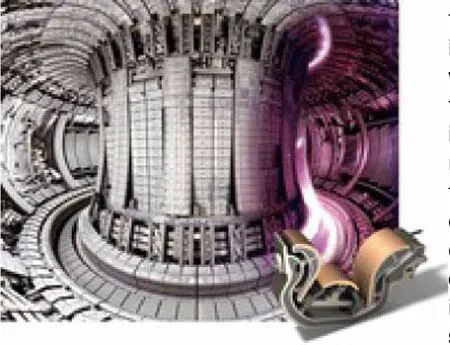

一直以来,笼罩在ITER核聚变反应堆项目——目前在法国建造的一个大型国际合作项目——头顶的一个最大问号便是用什么材料来涂装反应堆的内壁。要知道,它必须要能够抵挡10万摄氏度的高温,以及猛烈的粒子轰击。

如今,研究人员终于从用一个类似于计划在ITER中所使用的内层改装的目前世界上最大的核聚变装置中找到了答案。研究人员报告说,位于英国牛津附近的欧洲联合环形加速器(JET)的新的“像ITER一样的墙壁”是一种钨与铍的结合产物,与较早的核聚变反应堆所使用的内层相比,它被侵蚀的速度更为缓慢,并且吸收的燃料也更少。物理学家Peter de Vries表示:“这是一个非常棒的消息,因为它意味着我们为ITER所选择的材料是正确的。”

核聚变是为太阳和恒星提供能量的过程,或者说,它是最完美的能量来源。它所需的燃料(氘和氚)非常容易获取,并且几乎是用不完的,而这一过程也并不会产生任何温室气体或长期存在的核废料。

在早期核聚变反应堆中,最常见的反应堆内层是由碳构成的,这是因为它极耐高温与腐蚀,并且不会污染燃料被加热后所形成的等离子体。然而碳有一个最大的缺陷便是它非常“乐于”吸收氘和氚。对ITER来说,其反应堆会经常使用氚,因此对氚的吸收必须保持在最低限度,碳显然是不合适的。

由于并不存在一种完美的材料,因此研究人员不得不向使用两种材料的方案妥协。如今,大多数的内壁会涂装铍——这种金属对等离子体的污染最低,但其熔点却很低,无法耐受等离子体的高温。另一方面,在JET的底部有一个被称为偏滤器的装置,它类似于反应堆的排气管。这种装置会与等离子体接触,因此需要一种更为耐用的涂层。为此,研究人员使用了钨,并取得了很好的效果。

JET从2010年5月至2011年5月进行了一次内部改造,其间,研究人员用打算在ITER中使用的铍和钨替代了原有的碳内层。结果显示,在升级后的JET中,与之前的碳内壁相比,铍内壁在等离子体的影响下腐蚀速度要慢得多。研究人员在日前召开的一次会议上报告了这一结果。ITER是目前全球规模最大、影响最深远的国际科研合作项目之一,它的建造大约需要10年,耗资数十亿美元。ITER装置是一个能产生大规模核聚变反应的超导托克马克,俗称“人造太阳”。

How to Line a Thermonuclear Reactor

One of the biggest question marks hanging over the ITER fusion reactor project—a giant international collaboration currently under construction in France—is over what material to use for coating its interior wall.After all, the reactor has to withstand temperatures of 100,000°C and an intense particle bombardment.

Researchers have now answered that question by refitting the current world's largest fusion device, the Joint European Torus (JET) near Oxford, U.K., with a lining akin to the one planned for ITER.JET's new "ITER-like wall," a combination of tungsten and beryllium, is eroding more slowly and retaining less of the fuel than the lining used on earlier fusion reactors, the team reports."This was very good news, because it means that our choice of materials for ITER was the right one," says physicist Peter de Vries, task force and session leader at JET.

Fusion is the process that powers the sun and stars, and, potentially, it's the perfect energy source.The necessary fuels are easily accessible and virtually inexhaustible, and the process doesn't produce any greenhouse gases or long-lived nuclear waste.For fuel, it requires deuterium and tritium (forms of hydrogen with one and two extra neutrons, respectively, in their nuclei).These have to be heated so that they form plasma—an ionized gas—and when they reach about 150 million°C, the nuclei collide with such force that they overcome their mutual repulsion and fuse into a new, larger nucleus.The products of the reaction are a helium nucleus and a very energetic neutron, whose energy is later harvested in the form of heat.

But the harsh truth is it's not at all easy to run this fusion process in a controlled way.The current favored technique is to use a reactor called a tokamak, which employs powerful electromagnets to confine the plasma inside a doughnutshaped reactor vessel.The magnets aim to hold the plasma away from the walls of the vessel long enough for the nuclei to fuse but plasma can often shift around in unpredictable ways.If the plasma touches the wall, this can cool it to below reaction temperature and also scour off atoms of the lining material that poison the fusion reaction.And tritium is a radioactive isotope that reactor operators have to account for very carefully.Any tritium that embeds itself in the reactor wall has to be painstakingly extracted.

No fusion reactor has yet produced more energy than was put in to heat the plasma in the first place.But researchers have high hopes for ITER, the massive reactor with an estimated price tag of as much as $20 billion that is now being built in the south of France by China, the European Union, India, Japan, Russia, South Korea, and the United States.

The most common reactor lining, known as the first wall, in earlier fusion reactors was carbon because it is extremely resistant to high temperatures and erosion and doesn't pollute the plasma if atoms do get into it.Carbon's big drawback is that it's very happy to absorb deuterium and tritium.For ITER, the first reactor to use tritium on a regular basis, absorption of tritium has to be kept to a minimum, so carbon is out.