Effectiveness of a rehabilitative program that integrates hospital and community services for patients with schizophrenia in one community in Shanghai

Hua TAO, Lanjun SONG, Xin NIU, Xuehai LI, Qiongting ZHANG, Jia CUI, Hao CHEN, Zhenghui FU, Wenli FANG*

· Original article ·

Effectiveness of a rehabilitative program that integrates hospital and community services for patients with schizophrenia in one community in Shanghai

Hua TAO1, Lanjun SONG1, Xin NIU1, Xuehai LI2, Qiongting ZHANG1, Jia CUI1, Hao CHEN1, Zhenghui FU1, Wenli FANG3*

Background:One possible reason for the less than satisfactory long-term outcomes for schizophrenia is the lack of coordination between inpatient and community-based services.

Aim:Assess the effectiveness of a rehabilitation model for schizophrenia that integrates hospital and community services.

Methods: Ninety patients with schizophrenia participating in an integrated rehabilitation program at 10 community centers in Changning, Shanghai (intervention group) and 52 community-based patients with schizophrenia randomly selected from all patients in Changning participating in routine outpatient care (control group) were assessed at enrollment using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) and the Morningside Rehabilitation Status Scale (MRSS) and then re-assessed 1 year later by clinicians who were blind to the group assignment of the patients. The patients’ registered guardians (the vast majority were co-resident family members) were assessed at the same times using the Family Burden Scale (FBS), the Self-rating Depression Scale (SDS), the Self-rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) and the Social Support Rating Scale (SSRS).

Results:At enrollment the clinical status of patients in the two groups (assessed with PANSS) was similar but the social functioning measures assessed by MRSS were significantly worse in the intervention group than in the control group. After one year the improvement of both clinical symptoms and social functioning measures were significantly greater in the intervention group than in the control group. In the year of follow-up, 3 individuals (3.3%) in the intervention group and 6 individuals (11.5%) in the control group were re-hospitalized (Fisher Exact Test, p=0.074). The feelings of burden, depression, anxiety and reported social support among guardians of patients in the intervention group were not significantly different from those for guardians of patients in the control group either at the time of enrollment or after the 1-year intervention. However, guardians in the intervention group showed a significant decrease in depressive and anxiety symptoms over the one-year follow-up.

Conclusion:Rehabilitative approaches that integrate hospital and community services can improve clinical and social outcomes for patients with schizophrenia. Further development of these programs is needed to increase the proportion of patients who achieve regular employment (i.e., ‘community re-integration’) and to provide family members with better psychosocial support.

1. Introduction

Mental illnesses have become a global concern as health leaders, politicians and communities become aware of the magnitude of the health burden caused by these conditions. To address this issue the World Health Organization advocates expanding communitybased rehabilitation services so many countries, including China, have started to change the focus of mental health services from inpatient care in specialized hospitals to community-based services. Australia has provided a leading example of how services for patients with severe mental illness should be organized: multilevel treatment and rehabilitation service teams provide grading and recognition, hospitalization, risk evaluation, case management, community services, and safety outreach.[1]In China, the National Mental Health System Development Framework[2](2008-2015) highlighted current weaknesses in the communitybased management and rehabilitation of mental illnesses in China and made several recommendations for improvements.

In the late 1970s Shanghai established communitybased rehabilitation facilities (‘work stations’) that provided vocational rehabilitation and training for patients with severe mental disorders,[3]but the economic reforms of the subsequent two decades made work stations unviable (they were dependent on local factories providing piece work for the patients) so they have now all closed. Over the last decade Shanghai has gradually replaced the work stations with daytime rehabilitation and care centers. Starting in 2005, the development of these community service centers has been quite slow because family members prefer to keep their mentally ill relatives at home (to minimize the stigma). Patients who attend the centers tend to be those with more severe negative symptoms or those who family members are unable to manage at home. In 2009 these centers were uniformly named ‘Sunshine Heart Gardens’ and placed under the management of the Shanghai Disabled Persons’ Federation. Structured rehabilitation treatment programs that integrate community and hospitals services started at these centers in the beginning of 2010 but they still only provide services for a small proportion of patients with severe mental illness in the community.

This paper reports on an assessment of the rehabilitative model developed in Shanghai[4]that integrates the rehabilitative resources of specialized psychiatric hospitals with community-based services in the management of patients with schizophrenia.

2. Subjects and Methods

2.1 Subjects

The enrollment of participants in the study is shown in Figure 1. Individuals included in the study met diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia (based on the 3rdedition of theChinese Classification and Diagnostic Criteria of Mental Disorders[5]), were 18-55 years of age, were clinically stable, did not have serious physical illnesses or substance abuse problems, and provided written informed consent to participate in the study. Participants in the intervention group were patients enrolled in the Sunshine Heart Garden daytime community program in the Changning District of Shanghai, which is provided at 10 separate community centers in the district. Fiftytwo patients with schizophrenia from Changning district in the same age range as intervention group patients were randomly selected from all patients receiving standard community services (i.e., not participating in the Sunshine Heart Garden program). The guardian registered in the database (that is maintained for all patients in the community) for each enrolled patientwas selected as the family member respondent for the study.

Figure 1. Flowchart for the study

2.2 Intervention

The 10 community-based Sunshine Heart Garden centers each have one or two permanent staff members who coordinate services for patients who attend the centers from 9:00 to 15:30 on weekdays (most patients return home over lunch). Each center provides services to an average of 12 clients. Patients at the centers received the following services over the one-year course of the project:

a) Emergency response. Community mental health service staff provide timely intervention as needed when patients’ conditions change, when patients experience acute reactions to medications, or when patients create social disturbances. If necessary, medical staff from specialist hospitals assist in these emergency situations.

b) Rapid referral. A two-way referral system coordinated by staff members at the disease control and prevention offices in specialist psychiatric hospitals facilitates the rapid referral to specialist hospitals of clients at the Sunshine Heart Garden centers if their condition worsens and coordinates patients’ rapid return to the community for community-based rehabilitation after inpatient treatment.

c) Rehabilitation Services. A variety of rehabilitative services are provided at the Sunshine Heart Garden center by different types of professionals. Each day the services workers at the centers help patients monitor their medication, organize recreational activities (e.g., playing cards, reading magazines, dancing classes, etc.) and encourage patients to exercise (e.g., Tai Ji, calisthenics, etc.). Once or twice each month fulltime and part-time physicians from community health centers provide rehabilitative training based on the model developed by Liberman[6]that includes training in self-management of medications, self-monitoring of symptoms, and in the social skills needed to reintegrate into society. Therapists from specialist hospitals organize monthly handicraft and recreational activities. And each month a trip within the city is organized for the clients.

d) Family education and support. The offices for disease prevention and control centers at the psychiatric hospital developed a manual that provides families with the knowledge they need to promote the treatment and rehabilitation of their ill family member and for dealing with the stresses of managing a mentally ill family member. This manual is provided to all families and the content of the manual is discussed in six monthly training sessions held at the Changning Mental Health Center; about 90 family members attend each of the 80-90 minutes sessions.

e) Trial employment, return to the community. The original plan was to provide patients with occupational training and to help them enter formal employment, but over the one-year course of the project only 5 of the 90 patients (5.6%) were sufficiently functional to merit providing formal occupational training and it was not possible to organize trial employment for any of these individuals.

The 40 full-time and part-time community-based mental health service workers at the Sunshine Heart Garden centers, at the community health clinics, and at community administrative offices were trained by staff from the disease prevention and control offices at the specialty psychiatric hospitals who provided regular courses based on a structured rehabilitation training manual.

Patients in the community who do not participate in the Sunshine Heart Garden activities receive outpatient disease management; their family members receive education about the use of antipsychotic medications and general family support. These patients’ community management is primarily focused on preventing relapse and on preventing episodes of violence or socially disruptive behavior, not on rehabilitation. Community doctors and the local Centers for Disease Control office are responsible for managing these patients; typically the patient (or the patient’s family member) goes to the general health clinic for medication and follow-up care but sometimes clinicians may make a house call or contact the family by phone to check up on the patient.

2.3 Measures

At enrollment and again 12 months later the clinical and rehabilitative status of patients in the intervention and control groups were assessed using Chinese versions of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale[7](PANSS) and the Morningside Rehabilitation Status Scale[8](MRSS). The internal consistency of the total score and the three subscale scores of the PANSS (i.e., negative symptoms, positive symptoms and general psychopathology) are satisfactory (alpha=0.70-0.83) and the test-retest reliability is acceptable (ICC=0.77-0.89).[7]The MRSS has four subscales: Independence/Dependence (8 items); Activity/Inactivity (6 items); Social Integration/Isolation (8 items); and Effect of Current Symptoms (6 items). The internal consistency of the total score and the subscale scores is excellent (alpha=0.90-0.93) and the test-retest reliability is acceptable (ICC=0.74-0.80).[8]

Patients’ guardians were assessed at entry and 12 months later using one interviewer-completed survey and three self-completion instruments: the Family Burden Scale[9](FBS) is completed by investigators based on respondents’ answers to structured questions; the Self-rating Depression Scale[10](SDS), the Self-rating Anxiety Scale[11](SAS), and the Social Support Rating Scale[12](SSRS) are completed by family respondents after a simple introduction by the investigator. The internal consistency of the FBS total score is good (alpha=0.89) and the test-retest reliability is satisfactory (ICC=0.87).[9]Based on the data from the current study, the internal consistency of the SDS and SAS total scores are good (alpha=0.87 and 0.85, respectively). The internal consistency of the total SSRS score is good (alpha=0.90) and the test-retest reliability is excellent (ICC=0.92).[12]Most of the guardians were co-resident family members but 5 of the intervention group patients and 4 of the community-based patients were living on their own; in most of these cases the guardian had daily contact with the patient.

All evaluations were conducted by three psychiatrists with at least 5 years of experience who were provided with training in the use of the scales prior to starting the study. These evaluators were blind to the group assignment of the patients.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SAS software. Continuous measures were compared using t-tests and categorical variables were compared using chi-square tests. Nonnormal continuous variables were compared between the two groups using Wilcoxon rank sum tests. Withingroup changes over time were assessed using paired t-tests and comparisons of changes over time in the two groups were assessed using repeated measures ANOVA. The level of statistical significance was set at p<0.05. The study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the Changning Mental Health Center.

3. Results

3.1 Comparison of basic information between the two groups

Table 1 shows the results of comparing the basic characteristics of the 90 patients from the Sunshine Heart Garden and 52 patients sampled from Changning district. There were no significant differences in any of the characteristics assessed.

At baseline 71% of intervention group patients (64/90) and 77% of control group patients (40/52) were using second-generation antipsychotic medications (χ2=0.57, p=0.451); at the time of follow-up the respective percentages were 73% (66/90) and 79% (41/52) (χ2=0.54, p=0.463).

In the year of follow-up, 3 individuals (3.3%) in the intervention group and 6 individuals (11.5%) in the control group were re-hospitalized (Fisher Exact Test, p=0.074). None of the participating patients were involved in social disturbances during the one-year follow-up period.

3.2 Clinical and rehabilitative outcomes

Table 2 shows the results of comparing the pre- and post-treatment clinical and rehabilitative outcomes for the two groups of patients. The PANSS total score and the three PANSS dimension scores all improved significantly over the 1-year follow-up in the intervention group but not in the control group. There were no statistically significant differences between the groups in the PANSS total score or in any of the three PANSS dimension scores at baseline or at the 1-year follow-up. However, the four mean scores in the intervention group were all greater than those in the control group at baseline and they were all less than those in the control group at the 1-year follow-up so the improvement in all four measures (i.e., the mean difference between baseline and follow-up scores) was significantly greater in theintervention group than in the control group.

Table 1. Comparison of characteristics of respondents in the two groups

At baseline the MRSS total score and the four MRSS scale scores were all significantly worse in the intervention group than in the control group, indicating that patients enrolled at the Sunshine Heart Garden were more impaired than community-based patients who do not participate in this program. The MRSS total score and four MRSS scale scores all improved significantly over the year of treatment in the intervention group, but only the MRSS dependency scale score showed significant improvement in control group patients. Moreover, the magnitude of improvement in intervention group subjects was significantly greater than that for control group subjects in the MRSS total score and in the MRSS inactivity, isolation and symptom impairment scale scores, but the difference in the magnitude ofimprovement in the MRSS dependency scale score between groups did not reach statistical significance.

Table 2. PANSS and MRSS scores in the two groups at baseline and after 1 year of follow-up

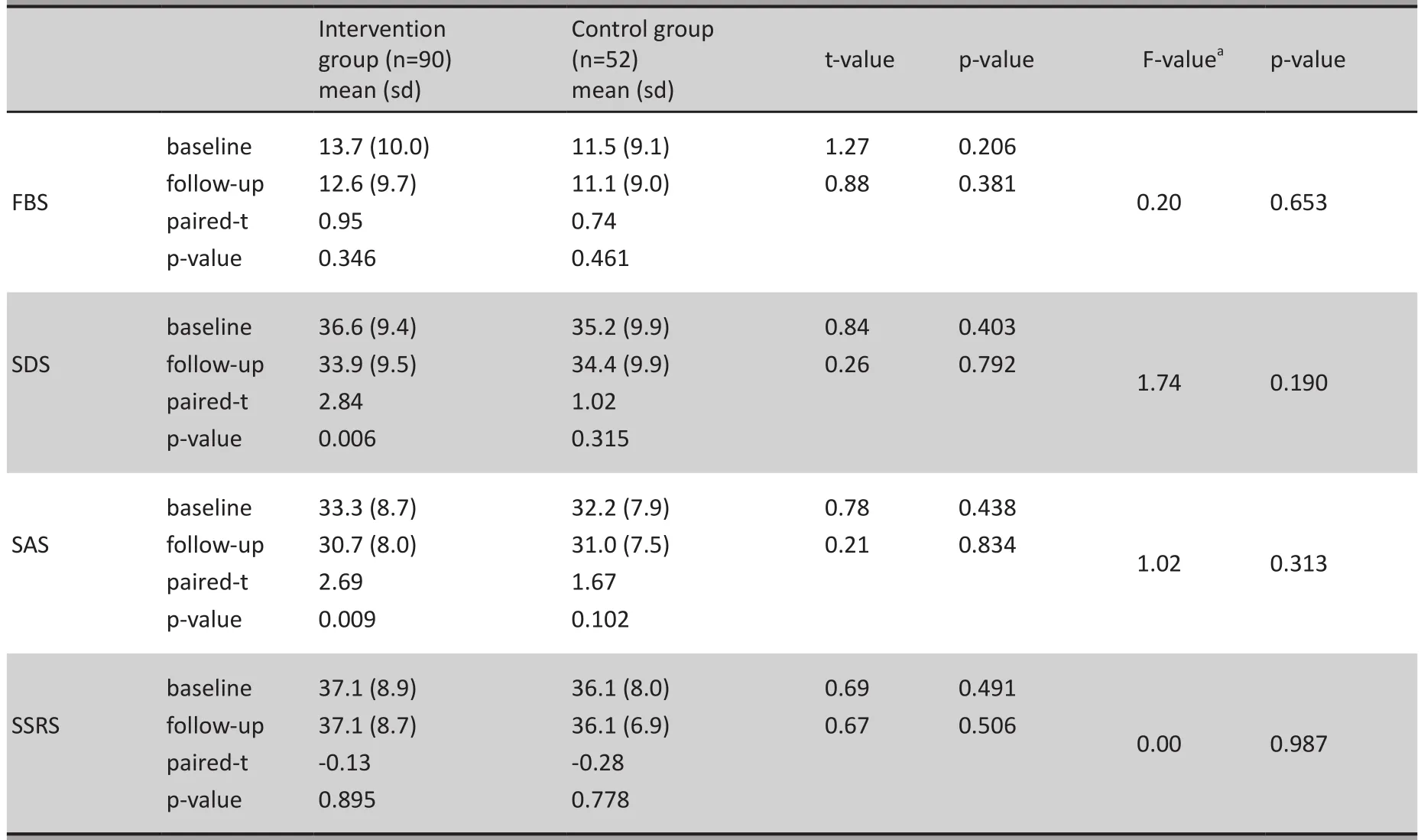

3.3 Family burden and social support

The results for patients’ guardians are shown in Table 3. None of the four measures used to assess psychological functioning of family members of patients with schizophrenia showed statistically significant differences between groups either before or after the 1-year treatment period. There was a significant improvement of self-reported depressive and anxiety symptoms in the intervention group guardians but not in control group guardians; there were no significant changes over the 1-year follow in reported feelings of burden or social support in either group. And there were no significant differences between groups in the magnitude of the change over the follow-up period for any of the four measures.

Table 3. FBS, SDS, SAS, and SSRS scores of patients’ guardians at baseline and after one year of follow-up

4. Discussion

4.1 Main findings

This 1-year controlled trial of community-based rehabilitation that used blinded evaluations of both clinical and rehabilitative outcomes clearly demonstrates the benefits of this intervention both in terms of clinical symptoms and in terms of social functioning. As measured by the PANSS and MRSS total scores and dimensional scores, the magnitude of improvement in the intervention group over the year of follow-up was greater than that in the control group who received standard community-based care; these differences were all statistically significant with the exception of that for the Dependency dimension of the MRSS which showed a non-significant trend (p=0.075) for the superiority of the intervention. The intervention group also experienced less re-hospitalizations than the control group over the follow-up period (3.3% vs. 11.5%) though this difference did not reach statistical significance.

These findings support the proposals of several experts who contend that rehabilitative models which effectively integrate community and hospital services are the best method for maximizing rehabilitative outcomes of patients with schizophrenia.[13]Despite on-going community services some patients still need to be periodically hospitalized so the continuity of services between the hospital and the community is an essential component of the model.[14]Other authors[15]suggest that such integrated models of care can also reduce relapses, re-hospitalizations and the occurrenceof socially disruptive behaviors; but these events are relatively infrequent so our sample was not large enough to assess these issues.

This model of care did not appear to have any beneficial effect on patients’ family members. Patient’s guardians in the intervention group reported less depressive and anxiety symptoms at the end of the follow-up than at enrollment, but there was no difference in the magnitude of the change in depressive and anxiety symptoms between guardians in the two groups. And there was no change in the perceived burden and social support of these individuals. The intervention was, of course, focused on patients and not directly on their family members so it is not that surprising that family members did not show significant benefits. Alternative rehabilitative models that include specific programs for family members, perhaps with the involvement of professional social workers,[16]may be needed to improve the psychological status of patients’family members.

4.2 Limitations

This case-controls study has several limitations. Clients at the Sunshine Heart Garden centers are self-selected (or, more commonly, selected by family members) so they are not typical of all patients with schizophrenia in the community. Concerns about the stigmatizing effect of using community services makes many families and patients reluctant to attend the Sunshine Heart Gardens so the patients that go there are often those who are more disabled. In the current study the basic characteristics and symptom severity of intervention group patients and control group patients were similar at enrollment but the social functioning measures assessed by the MRSS were much worse in intervention group patients. The substantial improvements seen with this intervention may not be replicated for patients who are less disabled. Further study with less severely disabled patients will be needed to determine whether or not a wide expansion of the program to less disabled patients would be feasible and effective. And cost-effectiveness analyses need to be conducted to compare the relative benefits of this and other approaches to community-based rehabilitation for persons with severe mental illnesses.

Given the broad scope of the project, which was spread out over multiple institutions involving a wide range of providers, it was difficult to obtain process measures about the fidelity of the application of the program activities. In future studies this will be necessary to identify components of the program that are and are not working. And if there is a desire to incorporate measures of relapse, re-hospitalization and socially disruptive behaviors as outcome measures much larger sample sizes will be needed.

Demographic information was not obtained on the guardians who participated in the evaluation component of the study so it is not known whether or not there were differences in gender, age or relationship with the patient between the guardians in the two groups. There are also potential problems in using officially registered guardians as the representatives of the patients’ families. In most cases guardians are co-resident family members, but this is not always the case. And the registered guardian is not necessarily the family member who is most directly involved in the management of the patient or the family member who is most emotionally affected by the patient’s condition. In subsequent studies it may be better to specifically select the primary family caregiver or to assess multiple family members for each enrolled patient.

The mental health network and the overall social environment in Shanghai are not representative of other urban locations in China and are completely different from the situation in rural parts of the country. The model of community-based mental health services assessed in this study would need to be substantially revised before its usefulness in other parts of the country could be assessed.

4.3 Significance

Community services for the mentally ill in Shanghai have undergone many changes over the last couple of decades. In the mid-1980s community management had three components — work-rehabilitation centers, a nursing network, and rehabilitation stations.[17]This system gave the government the role of coordinating the components and was effective and efficient at that time. However, the subsequent socioeconomic changes gradually made the work-rehabilitation stations (that depended on piece work from local factories) unviable[18]so there was a transition to hospital-based service networks that provided some community followup;[19,20]but these programs were primarily focused on treatment (i.e., medication management) and only secondarily focused on rehabilitation. As an alternative to this hospital-centered model, the integrated model described in the current paper is firmly centered in the community at the Sunshine Heart Garden centers, involves a wide range of community providers, and is strongly supported by the local Civil Affairs bureau and the All-China Disabled Persons Federation (the organizations that are primarily responsible for providing social services in China). This coordinated approach to services is in line with the WHO’s recommendations in the2001 World Health Report.[21]

Our study clearly demonstrates that this integrated, multi-component rehabilitative approach can improve both the clinical and social outcomes of communitybased patients with schizophrenia. Nevertheless, despite these improvements none of the patients in the intervention group were able to achieve regularemployment over the 1 year of follow-up so there is still a long road to travel before the goal of social reintegration can be achieved. And family members of the patients in the intervention group did not experience a psychological benefit from the improvements in the patients so the program did not really help those who carry the greatest burden of care-giving.

There are many models from other countries that could be considered when trying to improve the outcomes of our community-based rehabilitative approach. We could try to expand the psychological rehabilitation component of the services,[22,23]add alternative forms of hospitalization,[24]re-introduce sheltered workshops and supportive employment centers,[25]or develop an expanded role for professional mental health social workers as is the done in Hong Kong.[25]The feasibility and effectiveness of these alternative approaches in the Chinese context need to be assessed in detail in different locations around the country.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest related to this manuscript.

Funding

This project was supported by the Shanghai Bureau of Health (Number: 200925).

1. Liu TQ, Ma H, Chee Ng. Australia mental health. Journal of International Psychiatry2007;34(1):1-4. (in Chinese)

2. Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China. National Mental Health System Development Framework (2008-2015).Gazette of the Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China2008; 4: 14-18. (in Chinese)

3. Qu GY, Meng GR, Chen JX, Ren FM, Yao CD, Zhang L, et al. Role of work stations in the community rehabilitation of patients with schizophrenia.Shanghai Arch Psychiatry1986; 3(3):112-117. (in Chinese)

4. Xu Y, Chen Y. Effectiveness of the hospital-community integral mental health service.Shanghai Arch Psychiatry2008; 20(5): 276-278. (in Chinese)

5. Chinese Society of Psychiatry, Chinese Medical Association.Chinese Classification and Diagnostic Criteria of Mental Disorders. 3rd ed. Jinan: Shandong Science and Technology Press. 2001. (in Chinese)

6. Liberman RP.Social and Independent Living Skills. Los Angeles: Rehabilitation Research & Training Center in Mental Illness, 1986: 1-253.

7. He YL, Zhang MY. Use of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scales (PANSS).Journal of Clinical Psychological Medicine1997; 7(6): 353-355. (in Chinese)

8. Liu QF, Zhu ZQ, Meng GR, Huang BK, Wang GB. Reliability and validity of Morningside Rehabilitation Status Scale.Shanghai Arch Psychiatry1998; 10(3):147-149. (in Chinese)

9. Li J, Xiang MZ, Gao DJ, He J. Reliability and validity of Family Burden.West China Medical Journal1997; 12(1): 11-13. (in Chinese)

10. Wang WJ, Tan WY. Factor analysis of the Zung Self-rating Depression Scale.Guangdong Medical Journal2011; 32(16): 2191-2193. (in Chinese)

11. Wu WY. Self-rating Anxiety Scale.Chinese Mental Health Journal1999; 27(Suppl): 235-237. (in Chinese)

12. Liu JW, Li FY, Lian YL. Investigation of reliability and validity of the social support scale.Journal of Xinjiang Medical University2008; 31(1): 1-3.(in Chinese)

13. Luo MQ, Gao ZS, Lin SY, Guo CE, Li Z, Chen ZX, et al. An analysis on the cost-benefit and efficacy of sectorizational supervision and treatment in the community based for schizophrenia.Chinese Medical Herld2006; 3(15): 13-15.(in Chinese)

14. Song XZ, Kong LP, Yan J, Chen XJ. The development and current situations of overseas community psychiatry.Soft Science of Health2004; 18(3): 134-136. (in Chinese)

15. Wang K, Li LH, Song P, Zhao R, Xie Y, Liao WW, et al. Assessment on prevention and rehabilitation management of severe psychoses based on hospital-community propaganda in Shenzhen.Practical Preventive Medicine2010; 17(1): 157-159. (in Chinese)

16. Tong M. A study on the possibility and strategy of social work intervening in the recovery process of patients with mental illness in community.Journal of University of Science and Technology Beijing2005; 21(2): 35-39. (in Chinese)

17. Qu GY, Yan HQ. Prevention and treatment management pattern and status in Shanghai.Shanghai Arch Psychiatry1986; 3(3):100-106.

18. Su P. Urgently needed new model for the community management of psychiatric patients.Population Research2001; 25(4): 66-69. (in Chinese)

19. Yue Y, Zhang ZY, Ma YP, Su YJ, Xu YF, Ru RJ, et al. A 2-year followup study of effectiveness of individualized whole course case management in schizophrenic patients from community.Journal of Psychiatry2010; 23(3): 189-192. (in Chinese)

20. Zhou Q, Lin YQ, Yu YY, Zhang ZW. Effectiveness of community case management of patients with schizophrenia.Guangdong Medical Journal2010;31(14):1836-1838. (in Chinese)

21. World Health Organization.The World Health Report 2001. Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2001.

22. Temple S,Ho BC. Cognitive therapy for persistent psychosis in schizophrenia: a case-controlled clinical trial.Schizophr Res2005; 74(2-3): 195-199.

23. Shen F, Yang YC, Deng H, Zhang SS, Zhang ZQ, Tao QL, et al. The influence of psychosocial intervention on psychosis symptoms of schizophrenia after acute episode.Journal of Psychiatry2008; 21(3): 161-164. (in Chinese)

24. Liang CL. Community treatment of mental disorders in America.Journal of Clinical Psychological Medicine1998; 8(1): 50-52. (in Chinese)

25. Xue YL. Community rehabilitation of mental disorders in Hong Kong.Modern Rehabilitation2001; 5(7): 112-113. (in Chinese)

背景精神分裂症患者远期疗效不理想的可能因素之一是住院治疗与社区精神卫生服务间缺乏连贯性。

目的评估医院-社区一体化康复模式对精神分裂症患者康复的疗效。

方法在上海市长宁区 10 家社区卫生服务中心参与医院-社区一体化康复计划的 90 例精神分裂症患者作为干预组,从长宁区社区普通管理的门诊精神分裂症患者中随机抽取 52 例患者作为对照组。由不了解患者分组情况的医生在入组(基线)和12个月后采用阳性与阴性症状量表(Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, PANSS)、Morningside康复状态量表(Morningside Rehabilitation Status Scale,MRSS)评估患者情况。同时在上述两个时点采用家庭负担会谈量表(Family Burden Scale,FBS)、抑郁自评量表(Self-rating Depression Scale,SDS)、焦虑自评量表(Self-rating Anxiety Scale,SAS)和社会支持评定量表(Social Support Rating Scale,SSRS)评估患者法定监护人(绝大部分是与患者同住的家属)的情况。

结果入组时,PANSS评估结果显示两组的临床状况相仿,但是MRSS评估结果表明干预组的社会功能明显不如对照组。 干预 1 年后研究组的临床症状和社会功能的改善程度均比对照组显著。1年中,研究组有3 例(3.3%)住院,而对照组有 6 例(11.5%)(Fisher确切概率法,p=0.074)。无论是入组时还是1年后,两组监护人之间在感到的负担、抑郁、焦虑以及自我报告的社会支持等的差异均无显著性,但是干预组患者监护人的抑郁和焦虑症状在1年后得到改善。

结论医院-社区一体化康复模式能促进精神分裂症患者临床症状和社会功能的改善。今后需要进一步开展这一项目,来提高参与一体化康复模式的患者比例,并为患者家属提供更好的心理社会支持服务。

上海某区医院-社区一体化康复模式对精神分裂症患者的效果

陶华1宋兰君1牛昕1李学海2张琼婷1崔佳1陈浩1符争辉1方文莉3*

1长宁区精神卫生中心,上海

2上海交通大学医学院附属精神卫生中心,上海

3长宁区中心医院,上海

*通信作者:fangwl2004@hotmail.com

2011-10-19; accepted: 2012-02-08)

10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2012.03.003

1Changning District Mental Health Center, Shanghai, China

2Shanghai Mental Health Center, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China3Changning District Hospital, Shanghai, China

*Correspondence: fangwl2004@hotmail.com

- 上海精神医学的其它文章

- How to avoid missing data and the problems they pose: design considerations

- Cross-sectional study on the relationship between life events and mental health of secondary school students in Shanghai, China

- Superoxide dismutase activity and malondialdehyde levels in patients with travel-induced psychosis

- Randomized controlled trial on adjunctive cognitive remediation therapy for chronically hospitalized patients with schizophrenia

- Retrospective analysis of treatment effectiveness among patients in Mianyang Municipality enrolled in the national community management program for schizophrenia

- Consultation-liaison psychiatry in China