Chinese Gourmet Delight

By WEI MEIQING

THE CCTV food documentary series A Bite of China so titillated Chinese diners taste buds that its ratings soared way above those of established late night drama series and movies. Images of mouthwatering dishes from around China and tantalizing descriptions of their ingredients have made this seven-part series a tasty topic for gourmands on Weibo (Chinese Twitter), one of whom commented, “The sight of these delicacies made me so hungry I was tempted to lick the screen.”

nation of Gourmands

Although not broadcast at prime time the show nonetheless poached swathes of entertainment TV viewers. Rather than watch family saga soap operas or costume dramas these food lovers chose instead to be driven wild with gastronomic desire by shots of everyday dishes such as Xinjiang Nang (a crusty pancake-like bread), Tofu and rice noodles as well as exotic specialties like fungi fried in short- ening, fish dishes, oil-simmered bamboo shoots... the list of Chinese epicurean treats goes on and on.

Late night TV is normally the province of historical dramas about complex imperial court intrigues among empresses, concubines and power-mongering eunuchs. After the airing of the first part, the low-profile documentary A Bite of China achieved consistently top ratings in that time slot.

Unlike cooking shows, where the focus is on the skills of the chef host, A Bite of China takes in the selection and gathering of ingredients, contrasts in the foods and culinary customs of Chinas northern and southern regions, and changes over time in cooking methods. Its essential theme is the reverent enjoyment Chinese people take in both eating and cooking. Viewers have expressed appreciation online for the programs celebration of Chinas profound food culture and its multifarious cuisines, seeing it as confirmation of their innate patriotism. Com- ments include:

“The sound of the crisp chopping of pork filling for Shaanxi buns alone made me ravenous.”

“Im on a diet, and watching A Bite of China is a test of willpower that amounts to masochism.”

“The sight of bambooshoots being dug out, hams hanging from rafters, fishing nets glittering with their heaving catch, white steamed buns fresh out of the steamer, the ready smile of hawkers of yellow millet buns, and dough being slammed to stretch it into noodles all remind me of my beloved southern roots and bring me to the verge of tears.”

Viewers speak of the sensation they share of both brimming saliva glands and tear ducts when they watch the program, because it goes beyond cooking techniques and eating mores to explore the cultural and social context of food that maintains familial bonds and those among inhabitants of specific regions.

Ren Changzhen, the programs executive director, is a strong believer in the close relationship between agriculture, nature and food culture. “The series takes the viewing audience out of their everyday world to different environments throughout the country, such as villages and cave dwellings, forests, and coastal areas. This is one of the reasons why it is so popular.”

sensual Pleasure

As eating is a fundamental pleasure for people everywhere, food programs are popular throughout the world. “Even relatively amateurish cookery shows have high audience ratings, so its no wonder our series, with all its research and attention to detail, is popular. But we never expected such an overwhelming reaction,” Ren Changzhen said.

Eating is the favorite national pastime of the Chinese people. This is evident in the daily greeting among acquaintances,“Have you eaten?” no matter what time of day.

Young people seldom know anything about the origins of their favorite delicacies or the lives of the people that created them. A Bite of China fills this gap through its emphasis on the relationship between the people of different regions and their native foods, including the ingredients that go into them.

“We make a point of showing the common denominators of prepared foods as well as subtle differences. Noodles are a feature of both north Chinese cuisine, where they are made from wheat, and that of southern China, where they are made from rice flour. The Guilin rice noodles so popular across China are thought to have come about after the opening of the Lingqu Canal, which was built on the orders of Emperor Qinshihuang (259-210 BC) for the express purpose of transporting supplies from north to south China for his southern expedition,” said chief producer of the program Chen Xiaoqing, himself a gourmand who writes cookery columns in various newspapers and magazines.

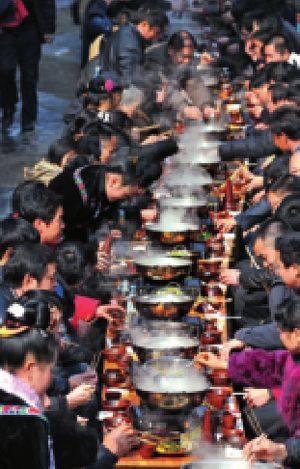

Food and agricultural products are inextricable from folk customs. Celebrations of the rice harvest, for instance, are held in certain areas of Yunnan and Guizhou provinces before it is stored in barns.Locals also present gifts of rice to the families of newborn infants. One program in the series features a birth- day dinner party for a senior resident of Dingcun hamlet in Shanxi Province, where guests selected the longest noodle in their bowls to present as a wish for his longevity.

“Ive watched the whole series and find that it does more than just display examples of particular cuisines by including their cultural heritage. It shows how our attitude to food ingredients can be a way of maintaining harmonious relations with nature,” cultural commentator Hu Yeqiu said.

A Bite of China showcases the diverse norms and modes of life of everyday Chinese people throughout the nation.

One show featured a family gathering at the suburban home of an elderly couple whose children and grandchildren live in the city. For them, eating with the whole family is their happiest time, so they spend hours making sticky rice cakes in preparation. Sad to say, these gatherings occur only every few months. Once their children and grandchildren get into their cars to drive back to the city, they are left once more to life in an empty nest.

“Rapid urbanization has changed the pattern of the extended family, but certain dishes and eating etiquette maintain customs that evoke time-honored legends. By featuring them the series carries a profound sense of history,” Chen Xiaoqing said.

Besides expressing their enjoyment of the program online, its fans also buy the ingredients of featured dishes.

Netizen Fengxi Shenlei wrote in a midnight micropost on Weibo that he had visited the shopping website Taobao at least 30 times looking for ingredients mentioned in the program. He is one of many who set out to create for themselves the gastronomic delights they have seen on A Bite of China.

Formerly lesser known tasty treats such as Moldy Tofu, fungi, ham from the old town of Nuodeng and the fan-shaped cheese from Dali, the last two from Yunnan Province, are all top-selling items on Taobao. Sales of the ham alone grew 17- fold within just five days after its appearance on the program.

Back to nature

Many believe that A Bite of China restores peoples pride in Chinese cuisine against the background of recent concerns about food safety, and rekindles their zeal for natural foods, in line with Chinese traditions and values.

There are also those who argue that although the series showcases all imaginable tastes and flavors, the fact remains that Chinese diners have and continue to be exposed to the dangers of recycled cooking oil and all manner of artificial food additives.

These hard facts have prompted online comments such as, “A Bite of China takes a cloud-cuckoo land view of Chinese restaurant fare, when the fact remains that some establishments still use cooking oil made from sewage.”

The documentary series displays tempting cuisines and the legends behind them. News items on the visual as well as printed media on food safety scandals, meanwhile, underline the sordid aspect of Chinas food industry.

“The warm glow that A Bite of China left its viewers with will soon fade and be forgotten, but the real, off-camera world still confronts us all in our daily life. We have to face it, think about it, and come up with a solution,” China Youth Daily reporter Cao Lin said.

Certain viewers take the cynical point of view that A Bite of China portrays Chinese dining as too good to be true, and that a version should be shot showing the other side of the coin. Some have even written the lead-in for it. “As winter approaches, people in southeastern China maintain the freshness of Chinese chives with chalcanthite (hydrated copper sulfate) while citizens of the North China Plain are busy cooking old leather shoes to make medical capsules...” Ren Changzhens response is that she is trying to accentuate the positive, and that the seamier side of Chinese life such as questionable food safety is not necessarily across the board.

Chinese people are at least more aware of the foods that should and should not go on their tables. A Bite of China evokes memories of traditional fare, and for this reason it is more than just a food documentary.

Food and travel programs occupy the lions share of the overseas documentary market, in which Chinese dishes have a distinct niche. Chen Xiaoqing concludes that discussing and displaying the changes China has experienced through its dishes and associated legends is a potent form of soft power that can reach every corner of the world without fear of misinterpretation.