固定化微生物技术在大气恶臭污染物处理中应用研究进展

万顺刚,李桂英,安太成*

1. 中国科学院广州地球化学研究所有机地球化学国家重点实验室,广东 广州 510640;2. 中国科学院研究生院,北京 100049

随着经济和科学技术的进步,在居民的物质和精神生活逐步得到提高的同时,常规污染物如粉尘、二氧化硫和氮氧化物等大气污染物的控制以及去除已经不能满足人们对大气环境质量日益增长的要求,恶臭污染物所导致的环境空气质量恶化的投诉问题逐渐增加。因此有关工农业生产和生活中排放的恶臭气体污染物的控制标准以及污染治理技术的研究,正逐步得到重视[1]。通常提到的恶臭污染物(Odor pollutants),在我国恶臭污染物排放标准 GB14554-93中给出了明确的解释,即一切刺激嗅觉器官引起人们不愉快感觉及损害生活环境的气味统称为恶臭,具有恶臭气味的物质被称为恶臭污染物。它们主要是通过刺激嗅觉细胞,经神经的传递作用而完成气味的鉴别。由于恶臭污染物具有挥发性的特点,因此恶臭污染主要是通过大气传播和扩散,作用于人的嗅觉器官而被感知的一种嗅觉污染。本文主要对恶臭有机污染物的固定化微生物处理技术的应用状况进行了综述,并对今后的研究方向和发展前景进行了展望。

1 恶臭有机物的来源、分类和危害

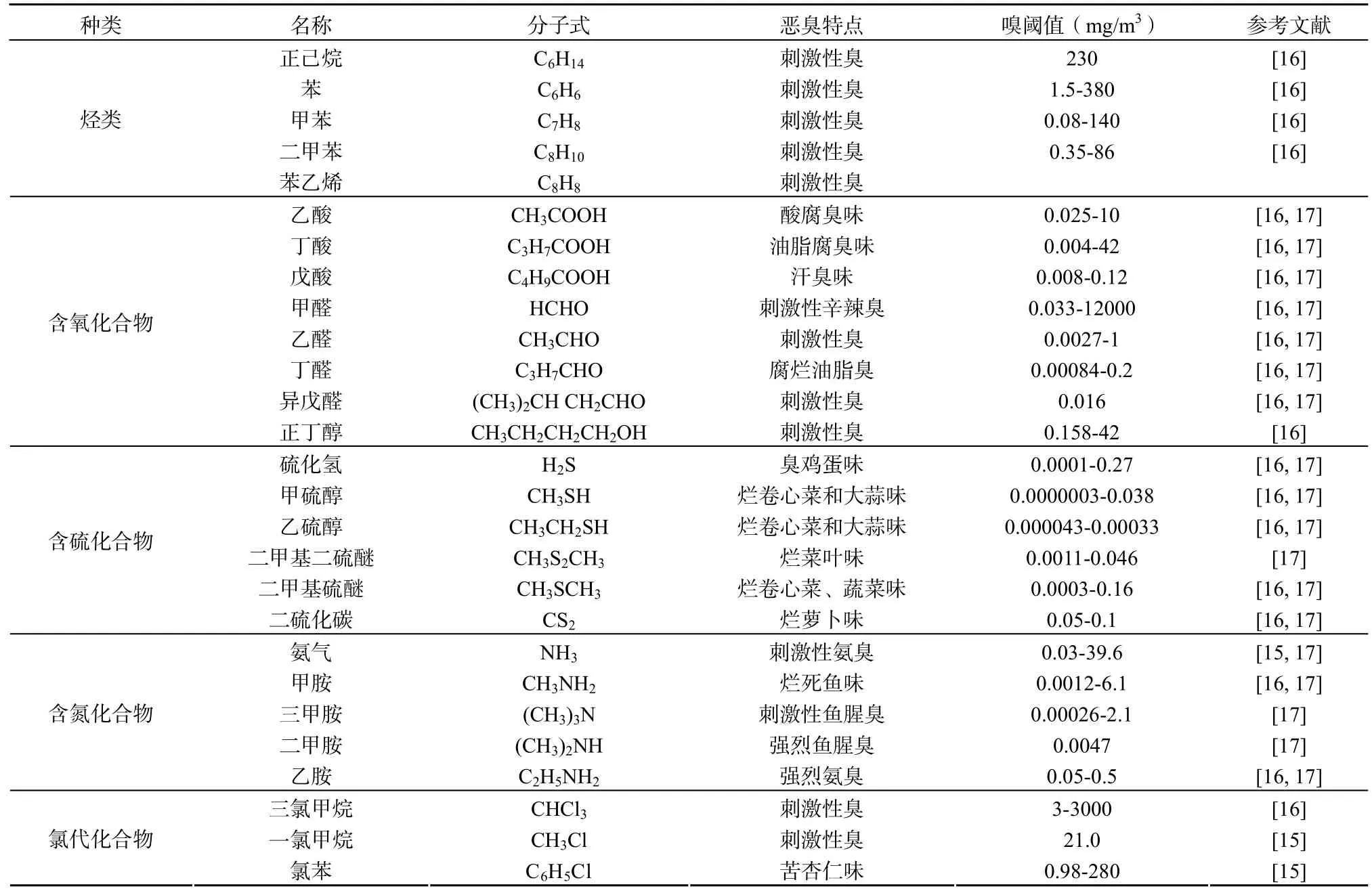

首先农牧业是恶臭污染的一个重要来源,农牧业的生产过程中产生的大量含有机物的各种废物在微生物的作用下分解,会排放出具有不同恶臭气味的空气污染物[2-5],特别是随着农业生产的发展及农产品加工规模经营不断扩大,与农业相关的恶臭污染已成为大气恶臭污染不可忽视的因素。其次,工业生产过程排放的恶臭污染物也是造成恶臭污染的最重要来源之一,这些工厂产生的恶臭污染物主要包括挥发性有机物(VOCs),尤其是挥发性有机硫化合物(Volatile Organic Sulfur Compounds,VOSCs)等[6-8]。再次,城市垃圾处理公共设施也是一个不容忽视的恶臭污染源,垃圾废物在通过城市垃圾厂、污水处理厂、堆肥厂等的处理过程中,排放出各种恶臭污染物[9-11]。所有这些恶臭污染物会对其周边的空气质量产生不良影响,甚至可以通过大气扩散作用到几公里以外的居民区。除了上述的恶臭污染来源以外,在工业生产和居民生活中燃烧煤炭,石油,煤气等燃料也会产生含硫和含氮恶臭污染物以及由于个人生活卫生不洁或者患有某种疾病所导致的恶臭污染,如腋臭和口臭等[12,13]。恶臭污染物作为一类重要的空气污染物,主要包括烃类、含氧有机物、含硫有机物、含氮有机物以及卤素及其衍生物等[14,15]。目前,种类繁多的恶臭污染物作为世界环境公害之一,具有自身的独特污染特点: 具有极低的嗅阈值低(臭味的最低嗅觉浓度)、排放强度大、污染源多、为点源和区域性污染以及以心理影响为主等。表1为部分典型的恶臭污染物的嗅阈值及污染特性。

由于恶臭污染物具有上述独特的污染特点,不仅会对恶臭污染源附近居住及工作人群的心理及感官产生影响,使人产生不愉快,烦躁和厌恶的情绪,降低工作效率和生活的质量[18],而且严重危害呼吸系统、消化系统、血液循环系统以及神经系统,同时有些恶臭污染物还具有干扰人体的内分泌系统,影响机体的代谢活动,甚至具有“三致作用”等[19,20],因此有必要采取适当的技术手段对大气中的恶臭污染物进行有效去除。

表1 典型恶臭污染物的名称、分子式、臭味性质、嗅阈值Table 1 The designation, molecular formulas, odor character and threshold of typical odorous pollutants

2 大气恶臭处理反应器类型及其应用现状

由于处理恶臭的生物技术种类较多,本文仅针对其中的固定化微生物技术在大气恶臭处理方面的应用进行介绍。固定化微生物技术是指利用将微生物接种到特定的生物反应器内的载体上,利用微生物自身代谢活动降解恶臭物质,使之降解矿化为CO2和H2O等最终产物,同时微生物利用污染物合成自身所需要的营养物质而进行生长和繁殖,从而达到无臭化、无害化的一种方法[21]。与常规的方法相比,它拥有物理和化学方法所不具有的特点:工艺简单、操作方便、运行稳定、处理效果好、无二次污染等,同时固定化微生物反应器通常在常温、常压下运行,运行时所需要的能耗低也比较低,尤其对于工农业生产过程所排放的大量、低浓度、无回收价值的恶臭污染物治理,固定化微生物技术具有明显的优势,具有广阔的应用前景。常用的能够应用于大气恶臭处理的固定化微生物技术主要包括生物过滤池、生物滴滤塔和生物膜反应器等。

2.1 生物过滤池(Biofilter)

生物过滤池是最早用于去除大气恶臭污染物的一种固定化微生物方法,目前主要用于去除气液分配系数小于1.0的恶臭污染物废气[22]。由于生物过滤池所用的载体通常为含有丰富微生物的土壤、堆肥以及泥炭等天然有机填料,天然有机载体本身能够为微生物生长提供所需要的营养元素,无需额外添加营养成分。因此,生物过滤池具有结构简单,投资少、运行费用低等优点。Hartikaine等[23]采用接种泥炭的生物过滤池处理浓度为 14 mg/m3的氨气,获得了较好的处理效果,去除能力可达 1.8 g/m3/d。Shah等[24]采用堆肥添加CaO的形式,研究去除养鸡场的氨气,在浓度为27 ppm时,去除率可以达到 97%。生物过滤池可以对 NH3、H2S和VOCs如甲苯等三种混合污染物进行有效降解,最高去除率可以达到100%[25]。同时,Chou和 Shiu[26]采用泥炭作为填料,在泥炭湿度为55-60%,pH在7.5-8.5的条件下,对容积负荷高达160 g/m3/h的甲胺可以有效降解。Tang等[27]采用堆肥和稻壳混合物作为填料,可以对浓度为78~841 ppmv的三乙胺有效降解,最高去除负荷可达140 g/m3/h,但高于140 g/m3/h时,发现底物具有明显的抑制作用。同国外相比,目前国内开展气相含氮恶臭有机污染物的研究还比较少,殷俊等[28]、丁颖[29]和胡芳等[30]采用接种堆肥或者活性污泥的生物过滤池对气相三甲胺的生物降解方面开展了净化研究工作,去除率可以达到99%以上。但是,生物过滤池在降解有机物时会产生酸性物质,会遇到填料的酸化以及设备腐蚀的问题,因此,需要在操作的过程中对pH进行控制才能更好地发挥其特性[31]。

2.2 生物滴滤塔(Biotrickling filter)

生物滴滤塔是在生物过滤池基础上进一步工艺改进的固定化微生物技术,不仅适合处理气液分配系数小于1.0的恶臭污染物,也适合小于0.1的恶臭污染物[22]。这是由于生物滴滤塔所采用的填料载体多为机械强度很高的无机或者有机物质,其本身不含有微生物并且不能为吸附在其表面的生物提供营养元素。因此,生物滴滤塔运行初期一般需要进行微生物接种,同时需要通过连续或者间歇喷淋微生物生长所需要的营养液促进微生物的生长与固定化。与生物过滤池相比,生物滴滤塔具有较高的空隙率和较小的床层压降。同时通过喷淋循环液进而可以有效控制反应器内微生物的生长环境(如pH、营养物浓度),避免反应产物在床层内的积累。这些改进使生物滴滤塔具有可操控性强等优点。目前已成为近年来固定化微生物技术方面的研究热点之一。有文献报道,采用活性炭作为填料,接种活性污泥等菌种,能够在停留时间为4 s时对浓度为20 ppmv的H2S有效去除,去除率可达98%[32]。甚至有文献报道在碱性(pH=10)的条件下,接种微生物的滴滤塔在停留时间为1~6 s的条件下,可以对浓度范围为2.5~18 ppmv的H2S进行有效地去除,去除率高达98%以上[33]。同国外相比,国内采用PVC弹性立体填料的生物滴滤塔研究结果表明,在H2S质量浓度小于1200 mg/m3时的去除率可以达到90%以上[34];黄树杰[35]采用滴滤塔处理硫化氢浓度为712.80-948.80 mg/m3的效率同样可以达到90%以上。此外,王京刚和张雅旎[36]采用改进聚乙烯醇法制成的固定化活性污泥颗粒填充生物滴滤塔在流量低于0.1 m3/h时,生物滴滤塔对乙硫醇的净化效率可达99.9%以上,当高于此流量时去除率明显降低。

此外,Kalingan等[37]采用接种微生物的泥炭和无机填料的生物滴滤塔,在室温下处理浓度为200 ppmv的含氨废气,去除率高达100%。有文献报道采用活性炭为填料,接种Paracoccussp.CP2可以对浓度为10~250 ppm的三甲胺(>85%)、二甲胺(>90%)和甲胺(>93%)等三种污染物进行有效去除,而三甲胺的生物降解性最差;而在添加菌种Parthrobactersp.CP1的情况下,三甲胺则可以被完全降解[38]。目前,生物滴滤塔技术也已经应用于甲苯[39,40]、苯乙烯[41,42]、甲醛和甲醇[43]、酚类[44]、酮类[45]以及挥发性脂肪酸[46]等的降解。同时也有文献报道了生物滴滤塔降解亲水性甲醇和非亲水化合物蒎烯的混合物[47]以及甲苯和三氯乙烯的混合物等[48]。

2.3 膜生物反应器(Membrane Bioreactor)

膜生物反应器是一类新型的用于废气处理的固定化微生物技术,主要是受到新材料的研制开发以及膜生物技术在废水处理中的成功应用的启示,人们开始关注膜技术在废气处理中的应用。膜生物反应器通常采用致密膜、多孔膜或者微孔材料膜作为载体,其中比较常用的膜为微孔膜[49]。用于接种的微生物在膜载体上生长并形成生物膜或者采取微生物悬浮在营养液中,通过膜的选择性渗透,污染物通过浓度的梯度扩散作用到达生物膜,并随后由微生物降解[50,51]。同生物过滤池和滴滤塔相比,在膜生物反应器内由于气体和生物膜分别位于纤维膜的两侧,因此气、液流量可分别控制,同时膜生物反应器可清除过量的生物量以防堵塞,并且可以提供一个大的气液接触界面提高质量传递的速率[51]。目前,膜生物生物反应器已经广泛用于烷烃等有机物的生物降解,并取得了较好的效果[49,51]。如采用接种Burkholderia vietnamiensisG4的多孔聚丙烯腈和聚二甲基硅氧烷膜作为载体的膜生物反应器可以在停留时间 2-28 s的条件下对浓度0.21-4.1 g/m3的甲苯净化,去除率可达78-99%[52]。在停留时间为 8-24 s时可以对废气中浓度为 38 mg/m3二甲基硫醚进行有效降解,去除率可以达到85-99%[53]。但是总体而言膜生物反应器的缺点是投资高,而且随着时间的增加,生物膜的活性可能有所下降。因此,同其他的固定微生物技术,如生物过滤池和生物滴滤塔相比,膜生物反应器降解恶臭有机物污染物的研究目前还仅限于实验室阶段,未见有工业应用的报道。

3 固定化微生物技术的主要影响因素

3.1 底物的影响

固定化微生物反应器内都装载有用于固定微生物的载体填料,在载体表面接种具有降解特定污染物的微生物菌种时,含有恶臭污染物的气体通过生物反应器内的填料层时,污染物从气相扩散到载体表面的液相或者生物膜,然后被微生物吸附、吸收和降解[10]。因此底物的物理化学性质将会决定生物反应器处理恶臭污染物的效果。有研究表明,污染物的分子组成会影响底物的可生物降解性,如在苯、甲苯、乙苯和二甲苯这四种物质中,最难降解的是邻二甲苯,降解率只有30%,其次为苯(45%),最容易降解的甲苯可以得到完全降解[54]。此外也有研究表明,在苯环上引入取代基团或者取代基团种类的增加会导致生物可降解性变差,如苯环上氯原子的数目增加到4个以上或者氯原子和羧基共同存在时[55]。此外,Ho等[38]的研究也表明,空间结构比较复杂的三甲胺的可生化降解性明显差于二甲胺和甲胺。由于大多恶臭气体污染物在降解过程主要受制于污染物从气相到生物膜的扩散速率控制,而对于水溶性好的恶臭污染物则受控于生物膜内微生物的降解速率。因此,醇类比醛类易于降解、酮类比酯类易于降解,但是所有这些化合物都要比长链烷烃容易降解,而芳香烃则是最难降解的[56]。所有这些结果都说明降解底物的物理化学性质会影响到其可生物降解性。因此,针对不同的物理化学性质的污染物可以有针对性地选择合适的固定化微生物反应器进行有效处理。

3.2 微生物的影响

固定化微生物法降解恶臭污染物,主要是利用固定在填料载体表面的微生物将恶臭污染物作为碳源和能源,同时通过新陈代谢活动来降解恶臭污染物。因此,微生物被认为是影响恶臭污染物降解效果的最重要因素。目前已经分离出的大量可以利用典型恶臭有机污染物作为单一碳源和能源而生长的优势菌种多为细菌,如含硫恶臭有机物降解菌、含氮化合物降解菌以及含氯化合物降解菌等,具体总结如表2所示,这些细菌大多数都属于杆状菌、丝状菌以及球菌等。大量研究表明将这些通过不同手段获得的微生物作为固定化微生物反应器所用的优势菌种,就可以针对含有特定目标污染物的废气进行有效降解。例如采用固定化单一菌种RG-1的生物滴滤塔可以对含硫恶臭有机气体污染物进行100%净化[57],固定化Paracoccussp.CP2的生物反应器可以对含三甲胺(去除率>85%)、二甲胺(去除率>85%)以及甲胺(去除率>85%)气体污染物进行净化等[38]。

与细菌相比,真菌具有对干燥、酸性等环境具有更强的适应性,所以真菌也被广泛用于气相中恶臭有机物的去除[90],特别是在苯系物的去除方面具有明显的优势(表3)。尽管朱国营等[91]对高效降解乙硫醇的生物过滤池中的微生物初步鉴定发现其优势菌种主要为真菌,但是他们并没有具体的优势真菌进行详细的鉴定。总之,我们也可以看出真菌也是处理恶臭污染物的一个重要生物资源,如何更有效地发挥真菌在固定化微生物技术处理恶臭污染物方面的应用是目前微生物资源研究的一个重要内容。

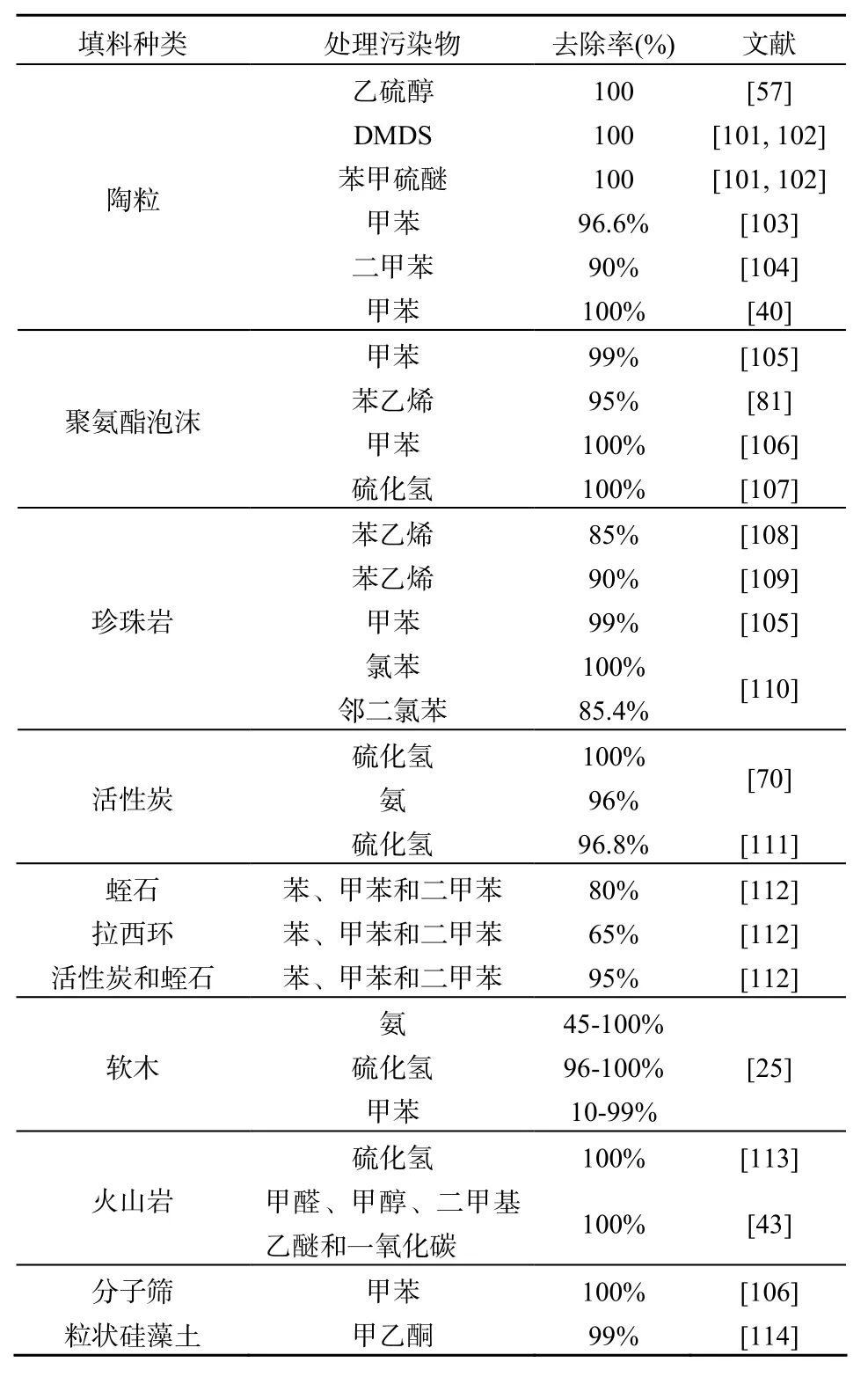

3.3 填料的影响

对于固定化微生物技术,固定微生物所用的载体是除了微生物菌种以外最重要的因素。固定化载体不但对恶臭污染物具有吸附作用,而且还能够为微生物的生长提供一个局部生态微环境和保留微生物生长所需要的营养等。由于传统富含微生物的天然填料如堆肥等在使用过程中容易压实引起压降的增加等缺点,并不太适合用于作为固定化微生物所用的载体。因此,目前大多采用机械性能好的有机和无机材质的合成材料作为固定化微生物的载体。表4总结了部分典型的固定化微生物所用的载体材料以及在处理各种恶臭污染物的效果比较。这些填料具有共同的特点,即大比表面积、合适的空隙率以及机械性能好,可以使固定化微生物反应器长期稳定运行,尤其是采用无机填料陶粒作为固定化微生物载体的生物滴滤塔可以长期稳定运行处理含硫恶臭气体污染物[101]。但是,关于选用什么样合适的载体用于那种固定化微生物反应器是最适合的,目前还没有一个比较一致的结论。所有这些都需要开展大量的工程实践的探索,以及设计加工更加具有通用性能的新型多功能填料才能充分发挥固定化微生物技术在恶臭污染物去除方面的应用优势。

表2 降解不同恶臭污染物的优势菌种Table 2 List of microorganisms for degrading representative odors pollutants

表3 降解不同恶臭污染物的优势真菌Table 3 List of fungus for degrading representative odorous pollutants

3.4 微生物固定化方法的影响

总体而言,处理大气恶臭污染物的微生物固定化方法与用于废水处理方面的微生物固定化方法基本上是一样,其固定化方法均主要包括[115-117]:吸附与附着法、包埋法、共价键合法、交联法和复合固定化法等等。而正是由于微生物的固定化方法及其固定化微生物技术在水处理领域的应用方面已经具有了很多非常不错的综述[115-117],因此本文并不想在该部分进行不必要的赘述。

3.5 pH值的影响

固定化微生物最佳降解恶臭污染物的能力一般都在其最佳的pH值范围(7~8之间)内,即大部分细菌和放线菌的最适宜生长范围[118]。而对于绝大多数的恶臭污染物在好氧生物降解过程中将会产生酸类物质,如含硫和含氮污染物中的硫元素和氮元素降解的最终产物为H2SO4和HNO3,继而会使固定化微生物反应器内pH下降,导致微生物自身的活性受到影响,进而影响到对恶臭污染物的去除效果[22]。比如在采用生物滴滤塔降解H2S过程中,当pH从2.0增加到7.0的过程中,虽然生物反应器对H2S的去除率基本都在95%以上,但是去除能力从13.35 g/m3/h增加到31.12 g/m3/h[119]。因此,如果要持续有效地发挥固定化微生物反应器的效率,有必要对固定化微生物反应器内pH进行调控。通常的方法主要是在固定化微生物反应器运行初期的固定化载体中添加固体缓冲物质来调节pH的变化,如在处理易产生酸性物质的恶臭污染物时,添加石灰和白云石可以有效地减缓固定化载体的酸化过程并提高污染物的去除能力[58,120]。当然也可以采用在固定化生物反应器内的循环液中添加适量的碱性或者酸性物质来实现中和反应,使反应器内的环境恢复到微生物生长所需要的适宜pH值范围。而对于处理不同特性的混合污染物时,如处理NH3和H2S混合恶臭气体时,H2S降解生成的酸就可以中和NH3引起的pH上升[121],因此就不需要采取额外的措施。

表4 典型降解不同恶臭污染物的填料载体Table 4 List of packing material for degrading representative odorous pollutants

3.6 温度的影响

环境温度也是影响固定化微生物反应器性能的重要因素之一,这主要是因为微生物的生长有一定的适宜温度范围,绝大多数的微生物的最适宜生长温度范围一般在25~35 ℃之间[22,56]。例如降解苯系物中甲苯、苯、乙苯以及二甲苯的最佳温度范围就在30~35 ℃之间[77,122]。但是,也有菌种可以在低温或者高温条件下能够对污染物进行有效地降解。如在温度为2~20 ℃范围内,通过接种泥炭-土壤或者乙烯氧化菌RD-4的生物反应器均对乙烯具有较好的去除效果[123,124]。以硫化氢和氨气的混合臭气为研究对象,在2~8 ℃时,氧化硫杆菌和亚硝化细菌对混合气体的去除率也可达99%[125]。除此之外,Luvsanjamba等[126]利用嗜高温(52 ℃)二甲基硫氧化菌种的膜生物反应器处理含有二甲基硫的高温废气,结果表明在停留时间为24 s时,污染物的去除率达到84%,容积去除负荷达到54 g/m3/h。总之,对于固定化生物反应器内的微生物要保持其高效的污染物降解活性,温度必须控制在其生长的最佳范围内,而对于实际废气温度过高或者过低,都需要进行预处理,以保证微生物降解污染物的活性。

5 固定化微生物降解恶臭污染物的机理研究进展

大气中恶臭污染物在固定而化微生物反应器内的去除宏观上主要是通过底物从气相中扩散到载体表面的生物膜或者液相进而被所固定化的微生物所降解,然后生成生物质和释放出CO2等最终代谢产物等[127]。由于气相污染物的降解首先必须从气相转入生物膜或者液相中,因此微观上固定化生物反应器降解恶臭气体污染物的途径和微生物降解液相中同一种污染物的过程基本相同。对于多数恶臭污染物的降解,首先是在母体化合物上引入羟基或者直接脱去某些基团,然后进一步发生系列生化反应而将目标污染物去除。如甲基叔丁基醚在微生物菌种的作用下先生成叔丁氧基甲醇,进一步的生成叔丁基甲酸然后再进一步转化成叔丁醇,或者叔丁基甲醚可以直接生成叔丁醇。叔丁醇在微生物的作用下进一步降解生成异丙醇以及丙酮等而最终得到完全分解[128]。正己烷在微生物菌种Rhodococcussp. EH831的作用下,首先通过引入羟基生成2-己醇,经2-己酮进一步矿化成丁醛,最后经丙醛、丙酮和乙醛等途径生成终产物CO2[79]。对于含有苯环结构的物质生物降解机理具有类似的结果,如Ralstonia pickettiiL2降解氯苯过程可以通过两条途径完成,首先是在微生物的作用下直接脱去氯原子的同时引入羟基生成邻苯二酚或者直接依次引入两个羟基生成邻氯二苯酚,然后这些中间产物在微生物的作用下经邻位或者间位开环而降解[89]。Na等[129]采用Rhodococcus opacus菌种降解液相中苯,首先生成邻苯二酚然后开环而得到降解。同时Liang等[130]采用Delftia tsuruhatensisAD9菌种对苯环含有氨基的化合物苯胺的研究结果也表明,苯胺在液相中的降解首先是通过在苯环上引入两个羟基生成邻苯二酚作为第一级降解产物,然后再以邻位或者间位开环的形式得到进一步的降解。Zhang等[131]研究同样表明液相中苯胺在微生物的作用下首先生成邻苯二酚,然后进一步开环后生成最终产物CO2。对于含硫化合物的生物转化机理和上述的引入羟基不同,如Gonzalez等[132]研究二甲基硫在Proteobacteria的作用下,直接生物降解生成中间产物甲硫醇,然后甲硫醇进一步矿化生成CO2和硫酸根。同样二甲基亚砜和二甲基二硫醚在微生物的作用下,首先生成一级降解产物甲硫醇,然后进一步被微生物降解生成硫化氢和甲醛,然后硫元素彻底矿化成硫酸根,而碳元素彻底矿化成CO2或生成生物质[133]。而对于非含苯环的含氮化合物如三甲胺等在好氧的条件下首先生成三甲胺氮氧化合物,然后依次生成二甲胺和甲胺,最后进一步矿化成最终产物,而在厌氧的条件下直接依次生成二甲胺和甲胺等代谢产物后被最终降解[71,72]。

6 研究展望

近年来固定化微生物技术在处理大气恶臭污染物方面显示了良好的应用前景。固定化微生物技术能够将大气中含有的各种有机恶臭污染物经微生物的同化作用和异化作用转化为CO2、水和生物质,从而消除恶臭污染物对环境的影响。但是在现有的研究基础上真正实现固定化微生物技术在大气恶臭污染物处理中的工业化应用,今后还需要加强以下几个方面的研究工作:

(1)优势微生物菌剂的培育。尽管目前已经有大量能够降解恶臭污染物的优势菌种,但是不同的恶臭底物降解所需要的菌种不同,因此针对不同恶臭污染物的不同特性,需要培养和获得更多的可用于恶臭污染物降解的优势菌种,包括能够适应处理实际环境条件下的低温和高温环境中使用的优势菌种以满足降解不同种类和不同条件下恶臭有机物的需要,在今后有效实现固定化微生物技术在实际大气恶臭污染物治理中的应用具有非常重要的研究价值。

(2)固定化载体的开发与改良。如何针对现有天然填料容易坍塌压实、无机填料比表面积小以及有机合成填料容易堵塞等不足问题,设计开发出更加廉价和稳定的填料载体,以便有利于固定化微生物的吸附和生长的新型多功能填料是实现固定化微生物技术工业化应用的重要研究方向之一。

(3)固定化微生物反应器的构建与优化。如何针对实际不同恶臭污染物的来源和特性,通过固定化载体和优势微生物的组装,有针对性地选择和构建高效固定化微生物反应器,并且系统开展固定化微生物技术在实际大气恶臭污染物工业应用化中操作参数的优化与筛选,有效缩短恶臭污染物在生物反应器中的停留时间,充分和高效地发挥固定微生物反应器的处理效率也是其工业化应用中非常关键的研究内容之一。

(4)固定化微生物技术与其它单元技术的联用。尽管目前有关固定化微生物技术净化恶臭污染物的研究也不少,但是固定化微生物技术处理实际恶臭污染物的工业化应用还比较有限,因此如何发挥现有固定微生物技术在处理恶臭污染物中的主导作用,并将其它大气处理的物理化学单元技术相结合,系统研究组合工艺不同组合方式、不同组合顺序等对其联用的影响,充分发挥各单元技术之间的独特优势,以期实现固定化微生物技术在工业实际恶臭污染物治理方面的应用是目前的一个重要研究方向。如果今后能够在以上几个方面开展更加系统和有成效的研究,可以预期在不远的将来固定化微生物技术必然能够在大气恶臭污染物的净化方面发挥更加出色的作用。

[1] 金紫阳, 徐亚同. 恶臭的污染及其治理[J]. 上海化工 2003,28,10-13.JIN Ziyang, XU Yatong. Odourous Pollutants and Deodorizatjon Treatments [J]. Shanghai Chemical Industry. 2003,28, 10-13.

[2] Johns, M.R. Developments in wastewater treatment in the meat processing industry: A review [J]. Bioresource Technology 1995,54,203-216.

[3] Lau A., Cheng, K. Removal of odor using biofilter from duck confinement buildings [J]. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part A 2007,42, 955-959.

[4] Shareefdeen Z., Herner B., Webb D., et al. An odor predictive model for rendering applications [J]. Chemical Engineering Journal 2005,113,215-220.

[5] Zhu J. A review of microbiology in swine manure odor control [J].Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2000,78, 93-106.

[6] Lin C.W. Hazardous air pollutant source emissions for a chemical fiber manufacturing facility in Taiwan [J]. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution 2001,128, 321-337.

[7] Xie B., Liang S.B., Tang Y., et al. Petrochemical wastewater odor treatment by biofiltration [J]. Bioresource Technology 2009,100,2204-2209.

[8] Yoon S.H., Chai X.S., Zhu J.Y., et al. In-digester reduction of organic sulfur compounds in kraft pulping [J]. Advances in Environmental Resear (China) 2001,5, 91-98.

[9] Liu Q., Li M., Chen R., Li Z.Y.,et al. Biofiltration treatment of odors from municipal solid waste treatment plants [J]. Waste Management 2009,29, 2051-2058.

[10] Shareefdeen Z., Herner B., Webb D., et al. Biofiltration eliminates nuisance chemical odors from industrial air streams [J]. Journal of Industrial Microbiology & Biotechnology 2003,30, 168-174.

[11] 盛彦清. 广州市典型污染河道与城市污水处理厂中恶臭有机硫化物的初步研究[D]. (中国科学院研究生院 (广州地球化学研究所)),2007.SHENG Yanqing. Primary study on odorous organic sulfides in typical polluted rivers and municipal wstewater treatment plants in Guangzhou urban [D]. Graduate School of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Guangzhou Institute of Geochemistry), 2007.

[12] Ratcliff P.A., Johnson P.W. The relationship between oral malodor,gingivitis, and periodontitis. A review. Journal of periodontology 1999,70, 485-489.

[13] Zeng X., Leyden J.J., Lawley H.J., et al. Analysis of characteristic odors from human male axillae [J]. Journal of Chemical Ecology 1991,17, 1469-1492.

[14] Mackie R.I., Stroot P.G., Varel V.H. Biochemical identification and biological origin of key odor components in livestock waste [J].Journal of Animal Science 1998,76, 1331.

[15] Ruth J.H. Odor Thresholds and irritation levels of several chemical substances: A review [J]. American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal 1986,47, 142 - 151.

[16] O'Neill D.H., Phillips V.R. A review of the control of odour nuisance from livestock buildings: Part 3, properties of the odorous substances which have been identified in livestock wastes or in the air around them [J]. Journal of Agricultural Engineering Research 1992,53,23-50.

[17] Gostelow P., Parsons S.A., Stuetz R.M. Odour measurements for sewage treatment works [J]. Water Research 2001,35, 579-597.

[18] Nimmermark S. Odour influence on well-being and health with specific focus on animal production emissions [J]. Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine 2004,11, 163-173.

[19] Nagao M., Yahagi T., Honda M., et al. Demonstration of mutagenicity of aniline and o-toluidine by norharman [J]. Proceedings of the Japan Academy. Ser. B: Physical and Biological Sciences 1977,53, 34-37.

[20] Guest I., Varma D.R. Teratogenic and macromolecular synthesis inhibitory effects of trimethylamine on mouse embryos in culture [J].Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part A 1992,36,27-41.

[21] Cox H.H.J., Deshusses M.A. Biological waste air treatment in biotrickling filters [J]. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 1998,9,256-262.

[22] Kennes C., Thalasso F. Review: Waste gas biotreatment technology [J].Journal of Chemical Technology & Biotechnology 1998,72, 303-319.

[23] Hartikainen T., Ruuskanen J., Vanhatalo M., et al. Removal of ammonia from air by a peat biofilter [J]. Environmental Technology 1996,17, 45-53.

[24] Shah S.B., Basden T.J., Bhumbla D.K. Bench-scale biofilter for removing ammonia from poultry house exhaust [J]. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part B 2003,38, 89-101.

[25] Park B.G., Shin W.S., Chung J.S. Simultaneous biofiltration of H2S,NH3and toluene using cork as a packing material [J]. Korean Journal of Chemical Engineering 2009,26, 79-85.

[26] Chou M.S., Shiu W.Z. Bioconversion of methylamine in biofilters [J].Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association 1997,47, 58-65.

[27] Tang H.M., Hwang S.J., Hwang S.C. Waste gas treatment in biofilters.Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association 1996,46,349-354.

[28] 殷峻, 许文锋, 丁颖, 等. 生物滤塔处理含三甲胺气体的研究[J].中国给水排水, 2009,25, 60-62.YIN Jun, XU Wenfeng, DING Ying, et al. Biological removal of trimethylamine by biofilter [J]. China Water & Wastewater, 2009,25,60-62.

[29] 丁颖. 生物滤器处理恶臭气体及其微生物生态研究[D]. (浙江大学),2007.DING Ying. Study on performances and microbial ecology of biofilters/biotrickling filters for odor removal [D]. (Zhejiang Unviersity), 2007.

[30] 胡芳, 魏在山, 叶蔚君. 生物法净化含 NH3、H2S和三甲胺的水产饲料恶臭废气的研究[J]. 环境工程2007,25, 41-44.HU Fang, WEI Zaishan, YE Weijun. The study on biopurification of NH3, H2S and trimethylamine- containing odor from aquatic feed [J].Environmental Engineering 2007,25, 41-44.

[31] Schroeder E.D. Trends in application of gas-phase bioreactors [J].Reviews in Environmental Science and Biotechnology 2002,1, 65-74.

[32] Duan H.Q., Koe L.C.C., Yan R. Treatment of H2S using a horizontal biotrickling filter based on biological activated carbon: reactor setup and performance evaluation [J]. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2005,67, 143-149.

[33] Gonza lez-Sa nchez A., Revah S., Deshusses M.A. Alkaline biofiltration of H2S odors. Environmental Science & Technology 2008,42, 7398-7404.

[34] 任爱玲, 郭静. PVC弹性填料生物膜法处理含H2S气体[J]. 化工环保 2000,20, 25-28.REN Ailing, GUO Jing. Treatment of H2S-containing gas by biofilm process with PVC elastic filler [J]. Environmental Protection of Chemical Industry 2000,20, 25-28.

[35] 黄树杰, 周伟煌, 陈凡植. 生物滴滤塔处理含硫化氢恶臭气体的试验研究[J]. 广东化工 2008,35, 106-109,158.HUANG Shujie, ZHOU Weihuang, CHEN Fanzhi. The study of biodegradation of H2S in biotrickling filter tower. Guangdong Chemical Industry 2008,35, 106-109,158.

[36] 王京刚, 张雅旎. 生物滴滤塔处理乙硫醇的实验研究[J]. 环境科学与管理 2007,32, 74-76.WANG Jinggang, ZHANG Yani. Experimental study on the treatment of odor gas containing ethanethiol by bio-trickling filter [J].Environmental Science and Management 2007,32, 74-76.

[37] Kalingan A.E., Liao C.M., Chen J.W., et al. Microbial degradation of livestock-generated ammonia using biofilters at typical ambient temperatures [J]. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part B 2005,39, 185-198.

[38] Ho K.L., Chung Y.C., Lin Y.H., et al. Biofiltration of trimethylamine,dimethylamine, and methylamine by immobilizedParacoccussp. CP2 andArthrobactersp. CP1 [J]. Chemosphere 2008,72, 250-256.

[39] 廖强, 田鑫, 朱恂, 等. 陶瓷球填料生物滴滤塔降解甲苯废气[J].化工学报2003,54, 1774-1778.LIAO Qiang, TIAN Xin, ZHU Xun, et al. Purifying waste gas containing low concentration toluene in trickling biofilter with ceramic spheres [J]. Journal of Chemical Industry and Engineering (China)2003,54, 1774-1778.

[40] Li G.Y., He Z., An T.C., et al. Comparative study of the elimination of toluene vapours in twin biotrickling filters using two microorganismsBacillus cereusS1 and S2 [J]. Journal of Chemical Technology &Biotechnology 2008,83, 1019-1026.

[41] Aalam S., Pauss A., Lebeault J.M. (1993). High efficiency styrene biodegradation in a biphasic organic/water continuous reactor [J].Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology39, 696-699.

[42] Djeribi R., Dezenclos T., Pauss A., et al. Removal of styrene from waste gas using a biological trickling filter [J]. Engineering in Life Sciences 2005,5, 450-457.

[43] Prado J., Veiga M.C., Kennes C. Removal of formaldehyde, methanol,dimethylether and carbon monoxide from waste gases of synthetic resin-producing industries [J]. Chemosphere 2008,70, 1357-1365.

[44] Hao O.J., Kim M.H., Seagren E.A., et al. Kinetics of phenol and chlorophenol utilization byAcinetobacterspecies [J]. Chemosphere 2002,46, 797-807.

[45] Raghuvanshi S., Babu B.V. Experimental studies and kinetic modeling for removal of methyl ethyl ketone using biofiltration [J]. Bioresource Technology 2009,100, 3855-3861.

[46] Tsang Y.F., Chua H., Sin S.N., et al. Treatment of odorous volatile fatty acids using a biotrickling filter [J]. Bioresource Technology 2008,99,589-595.

[47] Mohseni M., Allen D.G.. Biofiltration of mixtures of hydrophilic and hydrophobic volatile organic compounds [J]. Chemical Engineering Science 2000,55, 1545-1558.

[48] De Bo I., Van Langenhove H., Jacobs P. Removal of toluene and trichloroethylene from waste air in a membrane bioreactor [J].Environmental Science and Pollution Research International 2002b, 9,28-29.

[49] Kumar A., Dewulf J., Van Langenhove H. Membrane-based biological waste gas treatment [J]. Chemical Engineering Journal 2008,136,82-91.

[50] Reij M.W., Keurentjes J.T.F., Hartmans S. Membrane bioreactors for waste gas treatment [J]. Journal of Biotechnology 1998,59, 155-167.

[51] Mudliar S., Giri B., Padoley K., et al. Bioreactors for treatment of VOCs and odours - A review [J]. Journal of Environmental Management 2010,91, 1039-1054.

[52. Kumar A., Dewulf J., Luvsanjamba M., et al. Continuous operation of membrane bioreactor treating toluene vapors by Burkholderia vietnamiensis G4 [J]. Chemical Engineering Journal 2008,140,193-200.

[53] De Bo I., Van Langenhove H., Heyman J. (2002a). Removal of dimethyl sulfide from waste air in a membrane bioreactor [J].Desalination148, 281-287.

[54] García-Peña I., Ortiz I., Hernández S., et al. Biofiltration of BTEX by the fungusPaecilomyces variotii[J]. International Biodeterioration &Biodegradation 2008,62, 442-447.

[55] Adebusoye S.A., Picardal F.W., Ilori M.O., et al. Aerobic degradation of di- and trichlorobenzenes by two bacteria isolated from polluted tropical soils [J]. Chemosphere 2007,66, 1939-1946.

[56] Delhoménie M.C., Heitz M. Biofiltration of air: a review [J]. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology 2005,25, 53-72.

[57] An T.C., Wan S.G., Li G.Y., et al. Comparison of the removal of ethanethiol in twin-biotrickling filters inoculated with strain RG-1 and B350 mixed microorganisms [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2010,183, 372-380.

[58] Smet E., Langenhove H.V., Verstraete W. Long-term stability of a biofilter treating dimethyl sulphide [J]. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 1996,46, 191-196.

[59] Pol A., van der Drift C., Op den Camp H.J.M. Isolation of a carbon disulfide utilizingThiomonassp. and its application in a biotrickling filter [J]. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2007,74, 439-446.

[60] Kanagawa T., Mikami E. Removal of methanethiol, dimethyl sulfide,dimethyl disulfide, and hydrogen sulfide from contaminated air by Thiobacillus thioparusTK-m [J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 1989,55, 555-558.

[61] Cho K.S., Hirai M., Shoda M. Degradation of hydrogen sulfide byXanthomonassp. strain DY44 isolated from peat [J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 1992b,58, 1183-1189.

[62] Sercu B., Núñez D., Aroca G., et al. Inoculation and start-up of a biotricking filter removing dimethyl sulfide [J]. Chemical Engineering Journal 2005,113, 127-134.

[63] Pol A., Op den Camp H.J.M., Mees S.G.M., et al. Isolation of a dimethylsulfide-utilizingHyphomicrobiumspecies and its application in biofiltration of polluted air [J]. Biodegradation 1994,5, 105-112.

[64] Shu C.H., Chen C.K. Enhanced removal of dimethyl sulfide from a synthetic waste gas stream using a bioreactor inoculated with microbacterium sp NTUT26 andPseudomonas putida[J]. Journal of Industrial Microbiology & Biotechnology, 2009,36, 95-104.

[65] Chung Y.C., Huang C., Tseng, C. P. Operation optimization ofThiobacillus thioparusCH11 biofilter for hydrogen sulfide removal [J].Journal of Biotechnology 1996,52, 31-38.

[66] Cho K.S., Hirai M., Shoda M. Degradation characteristics of hydrogen sulfide, methanethiol, dimethyl sulfide and dimethyl disulfide byThiobacillus thioparusDW44 isolated from peat biofilter [J]. Journal of Fermentation and Bioengineering 1991a,71, 384-389.

[67] Cho K.S., Zhang L., Hirai M., et al. Removal characteristics of hydrogen sulphide and methanethiol byThiobacillussp. isolated from peat in biological deodorization [J]. Journal of Fermentation and Bioengineering 1991b,71, 44-49.

[68] Shinabe K., Oketani S., Ochi T., et al. Characteristics of hydrogen sulfide removal byThiobacillus thiooxidans KS1 isolated from a carrier-packed biological deodorization system [J]. Journal of Fermentation and Bioengineering 1995,80, 592-598.

[69] Takashi I., Tatsuro M., Tomoyuki N., et al. Degradation of dimethyl disulfide byPseudomonasfluorescensStrain 76 [J]. Bioscience Biotechnology and Biochemistry 2007,71, 366-370.

[70] Chung Y.C., Lin Y.Y., Tseng C.P. Removal of high concentration of NH3and coexistent H2S by biological activated carbon (BAC)biotrickling filter [J]. Bioresource Technology 2005,96, 1812-1820.

[71] Kim S.G., Bae H.S., Lee S.T. A novel denitrifying bacterial isolate that degrades trimethylamine both aerobically and anaerobically via two different pathways [J]. Archives of Microbiology 2001,176, 271- 277.

[72] Liffourrena A.S., Salvano M.A., Lucchesi G.I.Pseudomonas putidaA ATCC 12633 oxidizes trimethylamine aerobically via two different pathways [J]. Archives of Microbiology 2010,192, 471-476.

[73] Meiberg J.B.M., Harder W. Aerobic and anaerobic metabolism of trimethylamine, dimethylamine and methylamine inHyphomicrobiumX [J]. Microbiology 1978,106, 265-276.

[74] Zefirov N.S., Agapova S.R., Terentiev P.B., et al. Degradation of pyridine byArthrobacter crystallopoietesandRhodococcus opocusstrains [J]. FEMS Microbiology Letters 1994,118, 71-74.

[75] Mohan S.V., Sistla S., Guru R.K., et al. Microbial degradation of pyridine usingPseudomonassp. and isolation of plasmid responsible for degradation [J]. Waste Management 2003,23, 167-171.

[76] Zilli M., Del Borghi A., Converti A. Toluene vapour removal in a laboratory-scale biofilter [J]. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2000,54, 248-254.

[77] Park D.W., Kim S.S., Haam S., et al. Biodegradation of toluene by a lab-scale biofilter inoculated withpseudomonas putidaDK-1 [J].Environmental Technology 2002,23, 309-318.

[78] Jeong E., Hirai M., Shoda M. Removal of o-xylene using biofilter inoculated withRhodococcussp. BTO62 [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2008,152, 140-147.

[79] Lee E.H., Kim J., Cho K.-S., et al. Degradation of hexane and other recalcitrant hydrocarbons by a novel isolateRhodococcussp. EH831[J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2010,17, 64-77.

[80] Jang J.H., Hirai M., Shoda M. Styrene degradation byPseudomonassp.SR-5 in biofilters with organic and inorganic packing materials [J].Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2004,65, 349-355.

[81] Kim J., Ryu H.W., Jung D.J., et al. Styrene degradation in a polyurethane biofilter inoculated withPseudomonassp. IS-3 [J].Journal Microbiology Biotechnology 2005,15, 1207-1213.

[82] Bustard M., Whiting S., Cowan D., et al. Biodegradation of high-concentration isopropanol by a solvent-tolerant thermophile,Bacillus pallidust [J]. Extremophiles 2002,6, 319-323.

[83] Vainberg S., McClay K., Masuda H., et al. Biodegradation of ether pollutants byPseudonocardiasp. Strain ENV478 [J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2006,72, 5218-5224.

[84] Ferreira N., Maciel H., Mathis H., et al. Isolation and characterization of a newMycobacterium austroafricanumstrain, IFP 2015, growing on MTBE [J]. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2006,70,358-365.

[85] Jung I.G., Park O.H. Enhancement of cometabolic biodegradation of trichloroethylene (TCE) gas in biofiltration [J]. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering 2005,100, 657-661.

[86] Kan E., Deshusses M.A. Cometabolic Degradation of TCE vapors in a foamed emulsion bioreactor [J]. Environmental Science & Technology 2005,40, 1022-1028.

[87] Yu J.M., Chen J.M., Wang J.D. Removal of dichloromethane from waste gases by a biotrickling filter [J]. Journal of Environmental Sciences 2006,18, 1073-1076.

[88] Göbel M., Kranz O.H., Kaschabek S.R., et al. Microorganisms degrading chlorobenzene via ameta-cleavage pathway harbor highly similar chlorocatechol 2,3-dioxygenase-encoding gene clusters [J].Archives of Microbiology 2004,182, 147-156.

[89] Zhang L., Leng S., Zhu R., et al. Degradation of chlorobenzene by strainRalstonia pickettiiL2 isolated from a biotrickling filter treating a chlorobenzene-contaminated gas stream [J]. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2011, 1-9.

[90] Kennes C., Veiga M.C. Fungal biocatalysts in the biofiltration of VOC-polluted air [J]. Journal of Biotechnology 2004,113, 305-319.

[91] 朱国营, 刘俊新. 处理乙硫醇废气生物滤池中微生物的初步鉴定[J].环境科学学报2004,24, 333-337.ZHU Guoying, LIU Junxin . Identification of microorganisms in an EM-degrading biofilter [J]. Acta Scientiae Circumstantiae 2004,24,333-337.

[92] Prenafeta-Boldú F., Illa J., van Groenestijn J., et al. Influence of synthetic packing materials on the gas dispersion and biodegradation kinetics in fungal air biofilters [J]. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2008,79, 319-327.

[93] García-Peña E.I., Hernández S., Favela-Torres E., et al. Toluene biofiltration by the fungusScedosporium apiospermumTB1 [J].Biotechnology and Bioengineering 2001,76, 61-69.

[94] Zamir S.M., Halladj R., Nasernejad B. Removal of toluene vapors using a fungal biofilter under intermittent loading [J]. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2011,89, 8-14.

[95] Jin Y., Guo L., Veiga M.C., et al. Fungal biofiltration of α-pinene:Effects of temperature, relative humidity, and transient loads [J].Biotechnology and Bioengineering 2007,96, 433-443.

[96] Hernández-Meléndez O., Bárzana E., Arriaga S., et al. Fungal removal of gaseous hexane in biofilters packed with poly(ethylene carbonate)pine sawdust or peat composites [J]. Biotechnology and Bioengineering 2008,100, 864-871.

[97] Rene E.R., Veiga M.C., Kennes, C. Biodegradation of gas-phase styrene using the fungus Sporothrix variecibatus: Impact of pollutant load and transient operation [J]. Chemosphere 2010b,79, 221-227.

[98] Rene E.R., Spackov R., Veiga M., et al. Biofiltration of mixtures of gas-phase styrene and acetone with the fungusSporothrix variecibatus[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2010a,184, 204-214.

[99] Wang C., Xi J.Y., Hu H.Y., et al. Biodegradation of Gaseous Chlorobenzene by White-rot FungusPhanerochaete chrysosporium[J].Biomedical and Environmental Sciences 2008,21, 474-478.

[100] Qi B., Moe W.M., Kinney K.A. Biodegradation of volatile organic compounds by five fungal species [J]. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2002,58, 684-689.

[101] Wan S.G., Li G.Y., An T.C., et al. Co-treatment of single, binary and ternary mixture gas of ethanethiol, dimethyl disulfide and thioanisole in a biotrickling filter seeded with Lysinibacillus sphaericus RG-1 [J].Journal of Hazardous Materials 2011,186, 1050-1057.

[102] Wan S.G., Li G.Y., An T.C. Treatment performance of volatile organic sulfide compounds by the immobilized microorganisms of B350 group in a biotrickling filter [J]. Journal of Chemical Technology &Biotechnology, 2011, 86(9): 1166-1176.

[103. Lim J.S., Park S.J., Koo J.K., et al. Evaluation of porous ceramic as microbial carrier of biofilter to remove toluene vapor [J].Environmental Technology 2001,22, 47 - 56.

[104] Liu Q., Babajide A.E., Zhu P., et al. Removal of xylene from waste gases using biotrickling filters [J]. Chemical Engineering &Technology 2006,29, 320-325.

[105] Woertz J.R., van Heiningen W.N., van Eekert M.H., et al. Dynamic bioreactor operation: effects of packing material and mite predation on toluene removal from off-gas [J]. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2002,58, 690-694.

[106] He Z., Zhou L.C., Li G.Y., et al. Comparative study of the eliminating of waste gas containing toluene in twin biotrickling filters packed with molecular sieve and polyurethane foam. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2009,167, 275-281.

[107] Chen J.M., Jiang L.Y., Sha H.L. Removal efficiency of high-concentration H2S in a pilot-scale biotrickling filter [J].Environmental Technology 2006,27, 759 - 766.

[108] Weigner P., Páca J., Loskot P., et al. The start-up period of styrene degrading biofilters [J]. Folia Microbiologica 2001,46, 211-216.

[109] Paca J., Koutsky B., Maryska M., et al. Styrene degradation along the bed height of perlite biofilter [J]. Journal of Chemical Technology &Biotechnology 2001,76, 873-878.

[110] Oh Y.S., Bartha R. Design and performance of a trickling air biofilter for chlorobenzene and o-dichlorobenzene vapors [J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 1994,60, 2717-2722.

[111] Ma Y., Zhao J., Yang B. Removal of H2S in waste gases by an activated carbon bioreactor [J]. International Biodeterioration &Biodegradation 2006,57, 93-98.

[112] Ortiz I., Revah S., Auria R. Effects of packing material on the biofiltration of benzene, toluene and xylene vapours [J].Environmental Technology 2003,24, 265 - 275.

[113] Cho K.S., Ryu H.W., Lee N.Y. Biological deodorization of hydrogen sulfide using porous lava as a carrier ofThiobacillus thiooxidans[J].Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering 2000,90, 25-31.

[114] Cai Z., Kim D., Sorial G.A. Evaluation of trickle-bed air biofilter performance for MEK removal [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2004,114, 153-158.

[115] Zhou L.C., Li G.Y., An T.C., et al. Recent patents on immobilized microorganism technology and its engineering application in wastewater treatment. Recent Patent on Engineering [J]. 2008,2(1),28-35.

[116] 崔明超,陈繁忠,傅家谟,等. 固定化微生物技术在废水处理中的研究进展[J]. 化工环保,2003,23(5), 261-264.Cui Mingchao, CHEN Fanzhong, FU Jiamo, et al., Progress in the research on immobilized microorganism technology for wastewater treatment [J]. 2003,23(5), 261-264.

[117] 吴伟. 固定化微生物技术在处理高浓度有机废水中的应用[J]. 环境科学与管理,2011,36(7), 105-110.WU Wei. Applications of Immobilized Microorganism Technology in high concentration organic wastewater treatment [J]. Environmental Science and Management. 2011,36(7), 105-110.

[118] Leson G., Winer A.M. Biofiltration: an innovative air pollution control technology for VOC emissions [J]. Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association 1991,41, 1045-1054.

[119] Jin Y.M., Veiga M.C., Kennes C. Effects of pH, CO2, and flow pattern on the autotrophic degradation of hydrogen sulfide in a biotrickling filter [J]. Biotechnology and Bioengineering 2005,92, 462-471.

[120] Smet E., Langenhove H.V., Philips G. Dolomite limits acidification of a biofilter degrading dimethyl sulphide [J]. Biodegradation 1999,10,399-404.

[121] Cho K.S., Hirai M., Shoda M. Enhanced removal efficiency of malodorous gases in a pilot-scale peat biofilter inoculated withThiobacillus-ThioparusDw44. Journal of Fermentation and Bioengineering 1992a,73, 46-50.

[122] Lee E.Y., Jun Y.S., Cho K.S., et al. Degradation characteristics of toluene, benzene, ethylbenzene, and xylene byStenotrophomonas maltophiliaT3-c [J]. Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association 2002,52, 400-406.

[123] Elsgaard L. Ethylene removal by a biofilter with immobilized bacteria[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 1998,64, 4168-4173.

[124] Elsgaard L. Ethylene removal at low temperatures under biofilter and batch conditions[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2000,66, 3878-3882.

[125] 徐桂芹, 姜安玺, 闫波, 等. 低温生物处理含硫含氮气体效能和机理研究[J]. 哈尔滨工业大学学报 2005,37, 167-169.Xu Guiqin, JIANG Anxi, YAN Bo, et al. Evaluation of mechanism and result of H2S and NH3gas mixtures biodegradation in low temperature[J]. Journal of Harbin Institute of Technology 2005,37, 167-169.

[126] Luvsanjamba M., Kumar A., Van Langenhove H. Removal of dimethyl sulfide in a thermophilic membrane bioreactor [J]. Journal of Chemical Technology & Biotechnology 2008,83, 1218-1225.

[127] Deshusses M.A. Biological waste air treatment in biofilters [J].Current Opinion in Biotechnology 1997,8, 335-339.

[128] Schmidt T.C., Schirmer M., Wei H., et al. Microbial degradation of methyl tert-butyl ether and tert-butyl alcohol in the subsurface [J].Journal of Contaminant Hydrology 2004,70, 173-203.

[129] Na K., Kuroda A., Takiguchi N., et al. Isolation and characterization of benzene-tolerantRhodococcus opacusstrains [J]. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering 2005,99, 378-382.

[130] Liang Q., Takeo M., Chen M., et al. Chromosome-encoded gene cluster for the metabolic pathway that converts aniline to TCA-cycle intermediates inDelftia tsuruhatensisAD9 [J]. Microbiology 2005,151, 3435-3446.

[131] Zhang T., Zhang J., Liu S., et al. A novel and complete gene cluster involved in the degradation of aniline byDelftiasp. AN3 [J]. Journal of Environmental Sciences 2008,20, 717-724.

[132] Gonzalez J.M., Kiene R.P., Moran M.A. Transformation of sulfur compounds by an abundant lineage of marine bacteria in the alpha-subclass of the classProteobacteria[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 1999,65, 3810-3819.

[133] Kelly D.P., Smith N.A. Organic sulfur compounds in the environment:biogeochemistry, microbiology, and ecological aspects [J]. Advances in Microbial Ecology 1990,11, 345-385.