Corporate Governance and Accounting Conservatism in China*

Donglin Xind Song Zhu**

aSchool of Economics and Management, Tsinghua University, China

bSchool of Economics and Business Administration, Beijing Normal University, China

Corporate Governance and Accounting Conservatism in China*

Donglin Xiaaand Song Zhub,**

aSchool of Economics and Management, Tsinghua University, China

bSchool of Economics and Business Administration, Beijing Normal University, China

A principal-agent relationship exists among creditors, shareholders and management, and information asymmetry among them leads to asymmetric loss functions, which induces conservative accounting. This paper investigates the determinants of accounting conservatism using accrual-based measures and data from 2001 to 2006 in China. We find that a higher degree of leverage, lower level of control of ultimate shareholders and lower level of management ownership lead to more conservative financial reporting. We also find that political concerns and pressures among state-owned enterprises are greater than those among non-state owned enterprises, which leads to more conservative financial reporting among the former. However, a decrease in such concerns leads to a decrease in accounting conservatism. Overall, we find that among the determinants of conservatism in China, debt is the most important, followed by ownership, and that board has little influence.

JEL classification: G30; M41

Information asymmetry; Agency problem; Accounting conservatism; Political concerns; Corporate governance

1. Introduction

Conservatism is an important and basic principle in financial accounting. It stipulates that possible errors in measurement should be in the direction of understatement rather than overstatement of net income and net assets. If two estimates of earnings or assets to be received or paid in the future are approximately equally likely, then conservatism dictates that the less optimistic one be used (Statement of Financial Accounting Concepts No. 2, FASB).1However, if the two estimates are not equally likely, conservatism does not necessarily dictate using the more pessimistic one rather than the more likely one. Conservatism no longer requires deferring recognition of income beyond the time that adequate evidence of its existence becomes available or justifies recognizing losses before there is adequate evidence that they have been incurred (Statement of Financial Accounting Concepts No. 2, FASB).Under conservative accounting, the average market value is higher than the book value in the long run (Feltham and Ohlson, 1995; Zhang, 2000; Beaver and Ryan, 2000; Penman and Zhang, 2002). Such accounting recognizes bad news in a more timely way than it does good news, leading to asymmetric timeliness of earnings (Basu, 1997; Ball et al., 2000; Givoly and Hayn, 2000; Holthausen and Watts, 2001; Ball et al., 2003; Watts, 2003a). This type of conservatism is also known as conditional conservatism (Beaver and Ryan, 2005).2Conditional conservatism (Beaver and Ryan, 2005) or ex-post conservatism (Richardson and Tinaikar, 2004), also called news dependent conservatism (Chandra et al., 2004) and asymmetric income timeliness (Basu, 1997), implies more timely earnings recognition of bad than good news. Unconditional conservatism (Beaver and Ryan, 2005) or ex-ante conservatism (Richardson and Tinaikar, 2004), also called news-independent conservatism (Chandra et al., 2004), stems from the application of generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) or policies that reduce earnings independent of current economic news.Conservatism is beneficial for creditors,3Conservatism can protect the interests of creditors, providing creditors with new information to react to contract violations and enforce in a timely fashion their contractual rights, such as limiting the leverage, investment or dividend policy.minority stockholders,4Conservatism can be beneficial for minority shareholders as it can reduce the amount of inef ficient capital investment, restricting the power of management.the whole firm5Conservatism can reduce the level of information asymmetry between creditors and shareholders, lowering financing costs.and regulatory authorities6Conservatism can reduce the level of pressure and criticism from the public due to the standards that regulatory authorities have set.(Ahmed et al., 2002; Watts, 2003a; Francis et al., 2004; Nikolave, 2006; Ahmed and Duellman, 2007; Zhang, 2008).

Watts (2003a) proposes that one factor influencing accounting conservatism is regulations. He argues that standard setting authorities may face political pressure and public criticism. To reduce their political costs and protect the interests of investors, these authorities prefer conservative accounting (Bushman and Piotroski, 2006). However, Ball et al. (2003) contend that management incentives have a greater influence on financial reporting policies than have other factors. In China, managers face pressure from the government. This affects their political future and is thus likely to bea greater influence than either compensation incentives or market forces, as is the case documented in the US literature.7In China, management may be promoted and transferred to government/big groups, appointed as of ficials or awarded political titles if their or their firm’s performance is excellent.

The extant literature suggests that corporate governance may also significantly influence firm accounting and auditing decisions, affecting the quality of accounting information. However, corporate governance in China is significantly different from that in developed markets such as the United States, United Kingdom, or other European countries. In China, the government controls nearly 80% of publicly listed firms, an arrangement dramatically different from that of many other markets. The government, as the controlling shareholder, owns on average nearly two fifths of the stock of stateowned enterprises (SOEs). Before 2005, shares in these companies could not be freely traded at the market price on the open market.8Reforms were implemented in 2005 and 2006 concerning the circulation of those shares in the Chinese securities market. Since those reforms, SOE shares can be traded at the market price in the open market under some conditions.In contrast, management ownership is much lower in China, averaging only 0.03%. A compounding factor is that legal enforcement in China is very weak, which likely causes board monitoring and corporate governance mechanisms to be ineffective. These institutional characteristics raise the interesting questions of whether and how corporate governance influences accounting conservatism in China in particular, and in other emerging markets with similar institutions in general.

This paper investigates the determinants of conservative accounting using the data of listed firms in China and accrual-based measures of conservatism. Our results provide support for the theory proposed by Lafond and Watts (2008), namely, that information asymmetry constitutes an important reason for accounting conservatism, and are consistent with the finding of Ball et al. (2003) that management incentives have greater influence on accounting conservatism than have other factors. We find that a high level of debt, a low level of control rights of controlling shareholders, more layers of control in the corporate structure and a low level of management ownership are associated with a higher level of conservatism. We also find that accounting conservatism is greater among SOEs, which suggests that the concerns of managers about their promotion/ political careers and governmental pressures specific to SOEs likely play a role in shaping accounting practices. Our results reveal that, in China, debt is the most important factor affecting accounting conservatism, followed by ownership, and that the board has little effect.

Our research differs from other research that has investigated accounting conservatism among Chinese firms (Chen, Gul and Wu, 2008; Chen, Chen, Lobo and Wang, 2008) in that we use accrual-based measures rather than measures based on the Basu model. The Basu model captures conditional conservatism and relies heavily on the ef ficient market hypothesis, as it assumes that negative returns proxy for the badnews of firms. In China, negative returns are often caused by government regulations and intervention, and do not necessarily reflect the real economic performance of firms. Our accrual-based measures capture total conservatism, including conditional and unconditional conservatism (which are both pertinent in our setting), and are not susceptible to this issue. Hence, our results shed new light on the relation between corporate governance and accounting conservatism in China.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the related literature, and Section 3 presents our hypotheses. The empirical results are reported in Sections 4 and 5, and Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Literature Review

Contracting, litigation, taxation and regulation are four factors proposed by Watts (2003a) to explain accounting conservatism. There is much evidence in support of the contracting and litigation hypotheses; however, there is little empirical evidence to support the taxation and regulation hypotheses (Watts, 2003b). Lafond and Watts (2008) suggest that information asymmetry among equity investors is the key reason for accounting conservatism; that is, conservatism is caused by the non-verification of information, which results in asymmetric loss functions among related parties. When debt is greater, creditors require a higher level of conservatism in accounting reports to avoid potential losses (Ahmed et al., 2002; Watts, 2003a; Nikolave, 2006). Conservative accounting can also be beneficial for firms; hence, companies may have incentives to adopt conservative financial reporting policies (Francis et al., 2004; Zhang, 2008). Separation between ownership (cash flow rights) and control (voting rights) brings about agency problems (Jensen and Meckling, 1976), which result from information asymmetry, and accounting conservatism is one of the mechanisms addressing agency problems that protects investor interests (LaFond and Roychowdury, 2006). The potential benefits of conservatism in corporate governance suggest a positive relation between the strength of corporate governance and accounting conservatism (Beekes et al., 2004; LaFond and Roychowdury, 2006; Lim, 2006; Ahmed and Duellman, 2007), which indicates that good corporate governance will lead to greater conservatism in accounting.

The regulation hypothesis holds that regulatory authorities may face political pressure and public criticism (Watts, 2003a); thus, a higher level of investor protection is posited to lead to a higher level of conservatism (Bushman and Piotroski, 2006). Crosscountry studies provide some evidence in support of this hypothesis. Regulators in countries with strong judicial systems are assumed to be under more pressure and more likely to be criticized by the public for the standards they have set, and conservatism can easily reduce their political costs (Watts, 2003a). Therefore, in these countries, accounting reports are more conservative (Ball et al., 2000; Holthausen, 2003; Huijgen and Lubberink, 2003; Ball et al., 2003; Lubberink and Huijgen, 2006; Bushman andPiotroski, 2006). Ball et al. (2000) investigate how the different demands for accounting income in different institutional contexts cause the properties to vary across a wide range of countries. They find that in code law countries, accounting income is less timely, particularly in incorporating economic losses (Ball et al., 2000). Bushman and Piotroski (2006) find that firms in countries with strong judicial systems reflect bad news in earnings faster than firms in countries with weak judicial systems. They show that a higher level of judicial quality and usage of public bonds, and a more diffuse ownership structure lead to more conservative accounting. Also, strong public enforcement of securities law (but not private enforcement) delays the recognition of good news in earnings relative to the case when public enforcement is weak. In brief, differences in institutions, judicial systems and public enforcement determine the political costs for regulators. Research concerning different regions obtains similar results (Holthausen, 2003; Huijgen and Lubberink, 2003; Lubberink and Huijgen, 2006). Standard setting is an important determinant of conservatism; however, regulation enforcement and management incentives are more influential (Ball et al., 2003). Managers may also face pressure from the public and sometimes from the government, and some may care more about their political future than market compensation; thus, compliance costs to obey standards or other rules are different, which affects managerial incentives to comply with these rules. Differences in institutions, judicial systems, and public enforcement also influence the compliance costs of managers.

In China, nearly 80% of listed firms are controlled by the government, stock is highly concentrated and the level of management ownership is much lower than that in other countries. In addition, although there are many regulations, standards and laws, their enforcement is fairly weak. In other words, corporate governance in China is significantly different from that in the United States, United Kingdom or other markets. In China, management incentives and pressures differ among the various types of firms, especially between SOEs and non-SOEs. This provides us with an opportunity to investigate management incentives and conservative accounting in a single emerging economy. Basu (2009) points out that Chinese researchers can ask more general questions regarding alternative institutional arrangements. As the degree of state control in China is probably higher than that in most other countries, nonfinancial and budget information likely plays a greater role in China than elsewhere. It would be useful to study how information flows between government agencies and firms, and how the expectations of both parties are coordinated. Chen, Gul and Wu (2008) find that in China, the accounting reports of privately owned firms are more conservative than those of SOEs, indicating that incentives matter. They also find an interaction effect between incentives and accounting standards, in that firms with a greater demand for accounting conservatism report more conservatively in more recent periods characterized by more conservative accounting standards (Chen, Gul and Wu, 2008). Chen, Chen, Lobo and Wang (2008) examine the effect of both the borrower and the lender ownership structure on the accounting conservatism of the borrower and find that the financial reporting of state-controlled borrowers is less conservative. However, as they use the Basu model,they can test only conditional conservatism and thus do not investigate other corporate governance characteristics affecting agency costs that also influence conservatism.

3. Theory and Hypotheses

A principal-agent relation exists among creditors, shareholders and management (Jensen and Meckling, 1976), and information asymmetry among them leads to asymmetric loss functions, which induces conservative accounting (LaFond and Watts, 2008). In emerging markets, concentrated ownership is common, and agency problems are frequently observed between controlling or ultimate shareholders and minority shareholders and creditors.

3.1. Influence of Creditors

The greater is the uncertainty regarding future profitability, the greater is the risk that current dividends transfer resources to shareholders, which does not serve the interests of creditors. Timely loss recognition can exist before contracting and also provide creditors with new information so that they can react to contract violations and enforce in a timely fashion their contractual rights, such as restricting the leverage ratio, investment and dividend policy (Zhang, 2008), which means that conservative accounting will affect the efficiency of debt contracts based on accounting numbers (the net income and retained earnings reported). It also means more restrictions on dividends paid out (Watts and Zimmerman, 1986; Ahmed et al., 2002). Because of information asymmetry between creditors and shareholders, creditors will require more conservative accounting when they expect losses (Watts, 2003a; Basu, 1997).

However, debtors anticipate the effect of their behavior on future debt contracting: practicing conservative accounting can decrease information asymmetry and protect the interests of creditors, and help debtors to establish a good reputation and lower the cost of current and future debt. In this situation, adopting a conservative financial reporting policy can be beneficial for creditors and debtors (Zhang, 2008). As accounting conservatism can lower the cost of financing for debtors, firms are motivated to report their numbers under conservative accounting (Ahmed et al., 2002; Zhang, 2008). Conservative accounting can provide creditors with timely information on the downside risk of their loans, but borrowing firms have strong incentives to delay the bad news if the recognition of such news leads to contract violation. This effect is likely to be much stronger than the reward that creditors offer to borrowing firms for conservative accounting.9We appreciate this suggestion from the referee.However, financing activities are not a one-time game, and firms may turnto the securities market for more capital in the future. Once they violate the contract, they may be punished.10Violations are also determined by other corporate governance mechanisms, which are also enforced through laws and regulations. The influence of debt is not isolated from other key determinants.Thus, we posit the following hypothesis:

H1:Ceteris paribus, the greater the level of debt, the more conservative are the accounting reports.

3.2. Influence of Ownership

Ball et al. (2003) suggest that management incentives significantly influence the level of accounting conservatism. In China, management incentives and pressures differ depending on the type of firms. To obtain external financing, both SOEs and non-SOEs have incentives to manipulate accounting information. However, the former are affiliated with government and their objectives are more diverse, which makes them less eager to pursue opportunistic benefits through information manipulation compared with the latter. Non-SOEs face more financing constraints than do SOEs, and conservative accounting may lead to less profitable accounting earnings, which will result in the further restriction of external financing, both debt and equity. Therefore, the incentive for non-SOEs to pursue maximum profits will offset the incentive to practice conservative accounting.11This does not mean they will not report conservatively, as they also face pressure from creditors, minority shareholders and regulatory authorities.

Another significant difference between SOEs and non-SOEs is that management in the former must deal with greater political pressure and more constraints. It appears that in non-SOEs, managers are well monitored by principals, namely, entrepreneurs, and have incentives to improve corporate governance and maximize firm value. Corporate governance seems to be work better for non-SOEs than for SOEs. However, managers in non-SOEs face fewer political and legal restrictions than do those in SOEs, and they can handle many problems through unofficial channels or illegal means, which managers in SOEs dare not and cannot do. In non-SOEs, compliance with accounting principles and regulations is determined by the integrity of the management or the ultimate shareholders. Because punishments for accounting standard violations are inadequate and other regulations are not strongly enforced, the cost of violation is low for entrepreneurs. This problem is more severe in countries with a weak legal and institutional environment (Ball et al., 2003; Bushman and Piotroski, 2006), such as China. Therefore, the political cost for non-SOEs is much lower than that for SOEs.

The political pressure on managers in SOEs is much greater as they are constrained by restrictive rules and regulations.12Referring to GAAP violations, these will incur critique and pressure from the public, and offending firms may even be punished by regulatory authorities. Thus, regulation violation is bad news for management.Compliance with these directives is the mostimportant consideration for SOE management, as their violation will lead to criticism of management by regulatory authorities and the public, damage the reputation of managers and in extreme cases, ruin the political career of managers. This incentive for accounting conservatism related to political future is much greater among SOE managers than among their non-SOE counterparts. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2:Ceteris paribus, accounting reports of SOEs are more conservative than those of non-SOEs.13Our thanks go to the anonymous referee for pointing out that the higher level of accounting conservatism in SOEs compared to non-SOEs may be due to downward earnings management by the former to hide abnormal profits due to a government monopoly. In China, firms are more likely to report higher earnings because of the goals or planned objectives that government has set for them. Both SOEs and non-SOEs tend to report higher earnings; however, those of the former are a little more conservative than those of the latter. Another issue is that the accounting practices of SOEs are more conservative than those of non-SOEs, perhaps because the former have less incentive to manage earnings to ‘fool’ the market. Thus, in the empirical tests, we need to control for financing ability, scale effect, earnings management incentive and other related factors to minimize the influence of this possibility.

In developing markets with concentrated ownership, especially those in East Asia, managers are usually appointed and controlled by controlling or ultimate shareholders, and firm behavior reflects the will of these shareholders. Managers play a less important role than do those in firms in other markets, such as the United States, because the control of controlling shareholders and ultimate shareholders is significant. Ultimate shareholders with few cash flow rights can build powerful empires via the pyramid structure, and this incentive is evident in countries and regions with a weak legal system and undeveloped economy (La Porta et al., 1999; Claessens et al., 2000). As the number of layers in the pyramid increases, information asymmetry becomes more severe. The greater is the asymmetry of information, the greater is the demand for accounting conservatism by investors (Lafond and Watts, 2008). Various principal-agent problems are aggravated as the pyramid grows and the separation between control and cash flow rights increases, which also increases the demand for accounting conservatism. However, as the pyramid grows and information asymmetry becomes more severe, agency costs increase, and management or ultimate shareholders may exaggerate earnings and tunnel via aggressive reporting policies. In this situation, the accounting reports become less conservative as the number of layers in the pyramid increases.

As the supply and demand sides will have different financial reporting policies, the net result will be determined by the equilibrium.

H3a:Ceteris paribus, the number of layers in the corporate pyramid significantly influences the accounting reporting policy.

Among SOEs, the pyramid has somewhat different effects, as the incentive to create a pyramidal structure is to decentralize power, decrease the level of government interference and allow greater flexibility in the operation of listed firms in the free market economy (Fan et al., 2005; Zhu, 2006). Management can then play a greater role in firm operation, as there is less interference and pressure from the government. A political career may not be as easy to obtain, but it may not be as important as marketbased compensation.14It is dif ficult to tell which benefit (higher rank or more money) the manager will favor. A higher rank can bring more money, and more of other things. More layers in the pyramid will lead to a more distant relation with government; thus, the possibility to be promoted or appointed to government is less likely, which is less attractive among management in SOEs.Management may prefer higher earnings. Therefore, among SOEs, political pressure related to laws/regulations will decrease as the number of tiers in the pyramid increases. Based on the foregoing discussion, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3b:Ceteris paribus, among SOEs, the greater the number of layers in the corporate pyramid, the lower the demand for more conservative accounting reports, resulting in a lower level of accounting conservatism.

In countries with diffuse ownership, such as the United States, management is monitored by shareholders through laws/regulations and accounting information, leading to a demand for accounting conservatism. In countries with unsound monitoring mechanisms and institutions, controlling shareholders monitor management and can exploit investors (La Porta et al., 1999). As their control rights increase, dominant controlling shareholders rely less on accounting information, which lowers the demand for accounting conservatism. That is, more voting rights for ultimate shareholders results in a lower demand for conservative accounting.

As control rights increase, controlling shareholders can more easily tunnel the wealth of minority shareholders and use accounting information to manipulate earnings, which also decreases the level of the quality and conservatism of accounting information.15Although minority shareholders may demand more conservative accounting as they anticipate potential losses due to tunneling activities by controlling shareholders, because they have less voting power to put pressure on controlling shareholders or management, the effect of their demand may be insignificant.

H4a:Ceteris paribus, the greater are the voting rights of ultimate shareholders, the less conservative are the accounting reports.16Concentrated ownership can give more power to controlling shareholders but also aligns their interests with those of minority shareholders. Therefore, after a certain level, controlling shareholders may not tunnel, which means that control rights may be nonlinearly related with the financial reporting policy. We check for the nonlinear relation in the robustness testing. We find that this alignment effect is actually controlled by the divergence between control and cash flow rights (CV).

In countries with weak investor protection, the wealth of minority shareholders is often expropriated by controlling shareholders (Claessens et al., 2000; Fan and Wong, 2002), as the former have only a few cash flow rights and lack voting rights to challenge the entrenchment of the latter. The greater is the separation of voting rights from cash flow rights among controlling shareholders, the greater is their incentive to tunnel (Jensen and Meckling, 1976; La Porta et al., 1999), which stimulates the demand of minority shareholders for conservative accounting information to protect their interests. In some firms, ultimate shareholders do not directly control the firm; therefore, there is also information asymmetry between the ultimate shareholders and management. Also, the greater is the separation of control rights from cash flow rights, the greater is the risk that stockholders face, and thus they too will demand conservative accounting.

Such separation also triggers agency problems, and ultimate shareholders may be more likely to tunnel when divergence is great. Thus, greater divergence will lead to a lower level of accounting conservatism. Based on the foregoing discussion, we propose the following hypothesis:

H4b: Ceteris paribus, the separation of voting rights from cash flow rights significantly influences the level of accounting conservatism.

3.3. Influence of Management

Management has an information advantage compared to others; hence, managers have the opportunity to manipulate accounting information to maximize their interests (Jensen and Meckling, 1976; Watts and Zimmerman, 1986). For example, they may exaggerate firm performance to obtain greater compensation. They also have an incentive to adopt aggressive accounting to boost the stock price as this will increase their wealth. Watts (2003a) proposes that accounting conservatism can reduce the incentive and ability of management to overvalue earnings and equity, as conservative accounting delays revenue recognition and reduces the ability of management to hide expected losses. Therefore, accounting conservatism can prevent overpayment to management that results from limited liability and limited tenure.

The compensation and political future of managers are based on firm performance. Good performance will bring greater rewards and encouragement, so management in both SOEs and non-SOEs have incentives to improve firm performance. However, conservative accounting recognizes bad news in a more timely fashion than it does good news, and revenue recognition is asymmetric, which leads to a negative effect on firm performance. Therefore, management will select a financial reporting method tomaximize their own interests, and tend to be aggressive in reporting earnings, which will decrease the level of accounting conservatism.17Although the listed firms are actually controlled by controlling shareholders, management still has some power and influence regarding important decisions, such as the selection of the financial reporting policy. Both standards and contracts give them some leeway to exercise professional discretion.

H5:Ceteris paribus, the greater the stockholding by management, the less conservative the accounting reports.

Conservative accounting reports help to decrease information asymmetry between management and other stakeholders, and reduce the agency costs due to asymmetric loss functions and limited tenure of management (Watts, 2003a). A dominant board with more independent, or outside, directors will be more ef ficient in effective contracting, and better understand the benefits of conservative accounting reports; therefore, they will require more conservative financial reporting (Beekes et al., 2004; Ahmed and Duellman, 2007). However, a board dominated by inside directors, that is, those who are also management, will face less monitoring, and in this situation, management may adopt an aggressive accounting policy. The separation of the roles of CEO and chairman of the board will enhance board independence, which will improve the monitoring of management. In addition, as insiders tend to expropriate outside minority shareholders, such separation increases the level of shareholder protection. Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:

H6:Ceteris paribus, the more independent the board, the more conservative the accounting reports.

4. Data and Variables

4.1. Data and Samples

To avoid the influence of fundamental differences due to listed firms launching IPOs or delisting at different times, we use the same firms listed from 1999 to 2006, with 855 firms for each year. Before 1998, firms in China did not need to publish cash flow statements; hence, we start from 1999 for the ease of obtaining cash flow data.18Chinese listed firms have had to publish cash flow statements since 1998; however, the cash flow information for some firms is missing from the database or is incomplete. Therefore, we use the data since 1999.Since 2007, all listed firms in China have had to comply with the new accounting standards, which are quite different from the old ones; therefore, to keep the financial data consistent, we use those before 2007. The samples used to measure conservatism are from 2001 to 2006 as we need three years of financial information to compute theconservatism measures (Ahmed and Duellman, 2007; Qiang, 2007). After dropping firms with incomplete ultimate shareholder information, those whose growth exceeds 500%, those with leverage exceeding 100%19We also add all of those firms and the results are basically the same. Here, to minimize the influence of outliers, we drop some.and those that are ST firms,20,In China, when listed firms suffer losses for three consecutive years, the stock names will be labeled as ST, ‘Special Treatment’, which means if they still cannot make profit for two additional years after they are ST, they will be required to delist.21We delete all those firms that are ‘ST’ and the previous ones to minimize the influence of earnings management for ST firms on the measurement of conservatism.the final sample includes 4,149 firm-year observations for the 2001-2006 period. To minimize the influence of outliers, we winsorize the top and bottom 1% of the conservatism measures.

Information about ultimate shareholders is extracted manually from annual financial reports. Other financial data are from the Wind and CSMAR databases.

4.2. Variables

Most research in accounting conservatism uses the Basu (1997) model. However, this model suffers from measurement errors and has recently been criticized for being econometrically unstable; hence, whether it can measure conservatism is a subject of debate in the field (Ball and Shivakumar, 2005; Dietrich et al., 2006; Gregoriou and Skerratt, 2007). In addition, this model measures only conditional conservatism, but no unconditional conservatism. Conservative accounting leads to negative accruals, and the more negative are accruals, the more conservative are financial reports (Givoly and Hayn, 2000). We use the accrual-based measure of conservatism proposed by Givoly and Hayn (2000), Ahmed and Duellman (2007) and Qiang (2007).22This measure of conservatism also has drawbacks, as it is easily influenced by earnings management. In particular, for those firms suffering losses, the conservatism measure based on accruals is significantly influenced. Therefore, we drop all those ST firms and also use a dummy variable, ‘Loss,’ which equals 1 if a firm suffers a loss in the current year, and 0 otherwise.Because accounting accruals are reversed in the next period, we use three years’ cumulative accruals as our conservatism measure (Ahmed and Duellman, 2007). For ease of explanation, we multiply cumulative accruals by -1; thus, the greater is the value of this measure, the greater is accounting conservatism. Con11 is three years’ cumulative accruals multiplied by -1, accruals for each year equal to earnings after extraordinary items plus depreciation minus cash flow from operations, and then divided by total assets at year end. Con12 is three years’ cumulative accruals multiplied by -1, accruals for each year equal to earnings after extraordinary items minus cash flow from operations, and then divided by total assets at year end excluding the influence of depreciation. Firms often use extraordinary items to manipulate earnings; therefore, we also control for this, measuring conservatism using earnings before extraordinary items. Con21 is three years’ cumulative accrualsmultiplied by -1, accruals for each year equal to earnings before extraordinary items plus depreciation and minus cash flow from operations, and then divided by total assets at year end; Con22 is also three years’ cumulative accruals multiplied by -1, but each year’s accruals equal net income before extraordinary items minus cash flow from operations, and then divided by total assets at year end.23As some extraordinary items are outcomes of earnings management whereas other are not, it is dif ficult to say which measure is a better proxy of conservatism. In the literature, some use earnings plus depreciation whereas others use net earnings. To minimize measurement error, we use four measures to proxy for conservatism in the robustness test, and the results show that the four alternative proxies are basically consistent.

The influence of creditors is proxied by the debt ratio (Lev), which is equal to total liability divided by total assets at year end.24Although operating liability, such as payments to suppliers or employees, is similar to debt from banks, the former may not play a role in the requirement for conservative reporting; thus, we use debt from banks and other institutions as the leverage in the robustness test.Ownership structure variables include: the control chain or pyramid layers (Chain), measured by the corporate layers from ultimate shareholders to the listed firms, following Fan et al. (2005) and Zhu (2006); the control rights of the ultimate shareholders, proxied by the voting rights of ultimate shareholders considering the indirect holdings (V); the separation of ownership rights and control rights, proxied by the separation of cash flow rights from voting rights (CV), following La Porta et al. (1999) and Claessens et al. (2000)25CV equals cash flow rights (C) divided by control rights (V). A lower CV value means greater separation between cash flow and control rights.; and the nature of the ultimate shareholders (State), indicated by a dummy variable equal to 1 if the ultimate shareholder is the government, and 0 otherwise. Management ownership (Man) is the percentage of shares held by firm management of total shares at year end. Board independence is proxied by: (1) the ratio of outside directors to total directors on the board (Out), (2) the ratio of directors who are also management to total directors on the board (Inside)26In China, some directors are outside or independent directors from universities or unrelated firms, others are members of management in the firms, such as the CEO, CFO or CIO and still others are appointed by shareholders to monitor management. Therefore, the sum of Out and Inside is not necessarily one and is seldom one.and (3) a dummy variable equal to 1 if the same person serves as both CEO and chairman of the board (CC), and 0 otherwise.

Fundamental aspects of listed firms include: cash flow from operations to total assets at year end (CFO); firm size, proxied by the natural log form of total assets at year end (Size); future prospects, proxied by the growth rate of revenue (Growth); earnings management inclination, proxied by a dummy variable (Loss) that is equal to 1 if a firm suffers a loss in the current year, and 0 otherwise; and industry (Inds, 11 dummy variables for 12 industries excluding the finance industry, based on the categorization scheme of the China Securities Regulatory Commission) and year (Years, five dummy variables for six years) effects.

5. Empirical Analysis

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

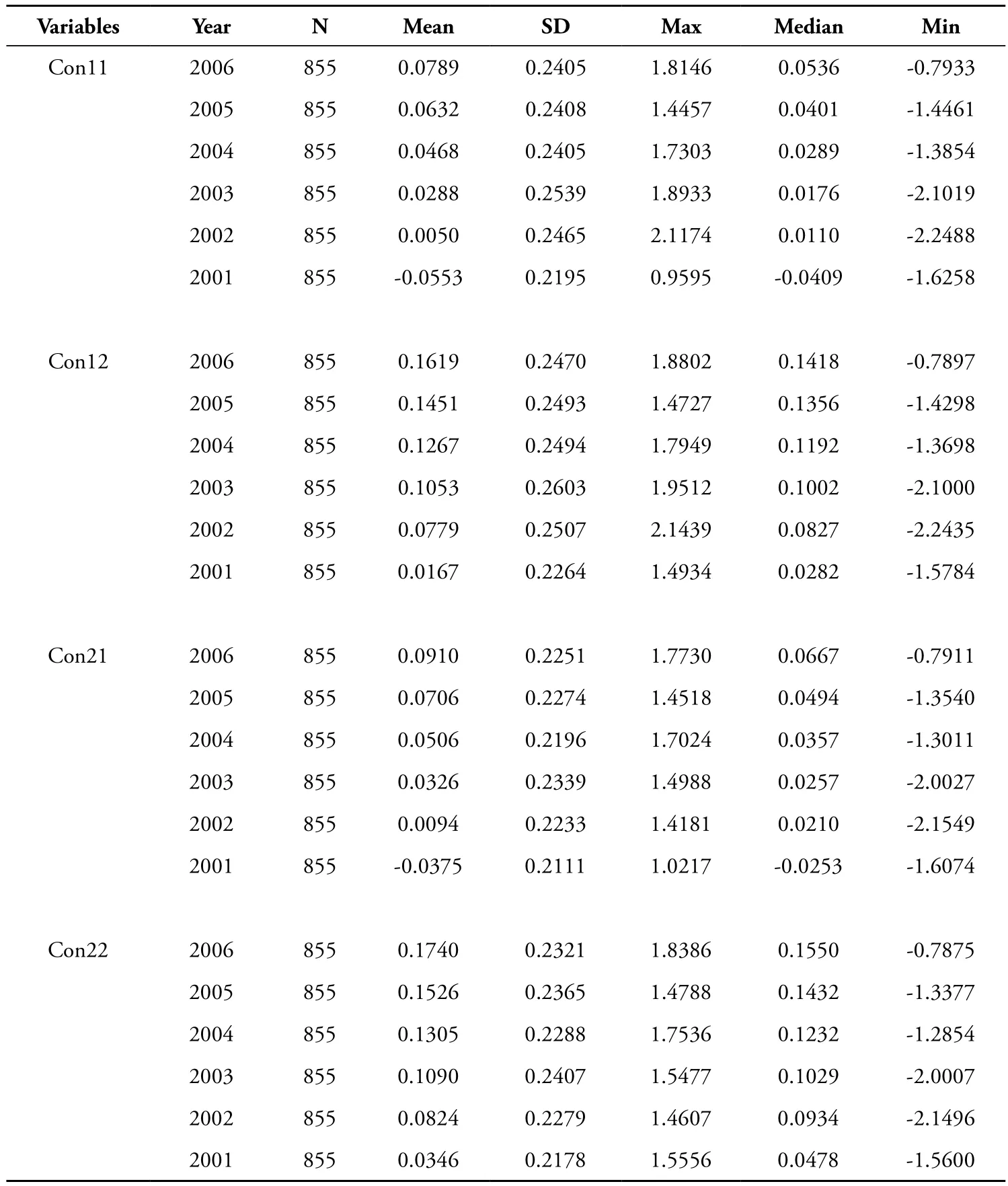

Table 1 shows the statistics for the conservatism measures based on the cumulative accruals in each firm year.27None of these numbers is winsorized.

Table 1. Evolution of Accounting Conservatism in Chinese Listed Firms - Statistics

Figure 1. Evolution of Accounting Conservatism in Chinese Listed Firms Based on Earnings before Depreciation

Figure 2. Evolution of Accounting Conservatism in Chinese Listed Firms Based on Earnings after Depreciation

The statistics in Table 1 and graphs in Figures 1 and 2 show that since 2001, the level of accounting conservatism of listed firms in China has increased each year, consistent with the finding of Qu and Qiu (2007) that with the implementation of more conservative accounting standards and the enforcement of regulations, firms in China have become more conservative in their financial reporting.

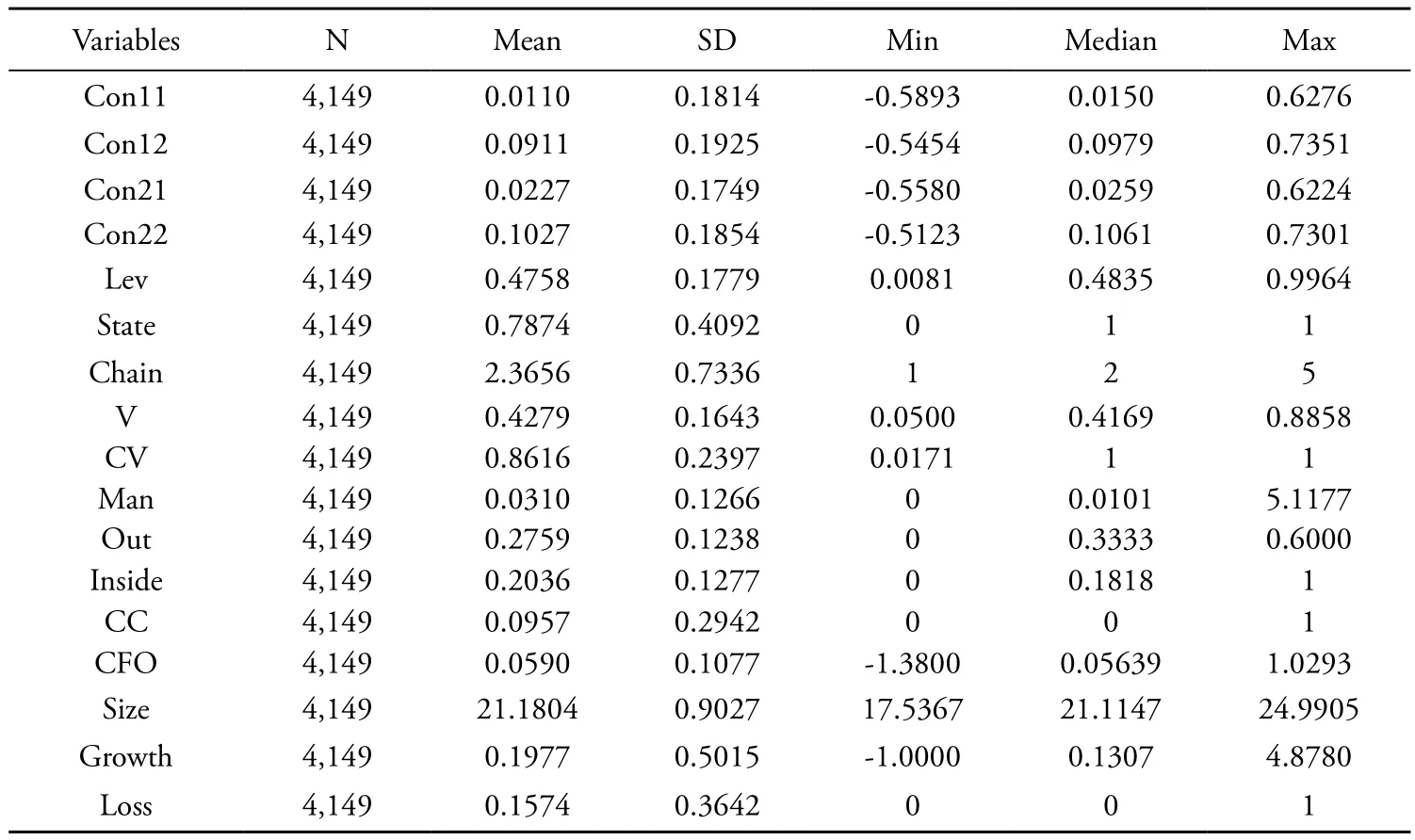

Table 2 presents the statistics for the regression variables of the sample firms.28The conservatism measures are winsorized.The values of the conservatism measures based on earnings before extraordinary items are 0.0110 and 0.0227 on average, and those of the other two measures are 0.0911 and 0.1027. Positive numbers indicate a conservative financial reporting policy, but some firms still have aggressive financial reporting practices.

The average debt ratio of the sample firms is around 47%, and the median is about 48%. Among our sample firms, about 78% are SOEs, which means that in the Chinese securities market, only about 20% of firms are not controlled by the government. The average number of layers in the corporate pyramid is 2.36, which means that ultimate shareholders usually control firms via at least one intermediate firm, with some even setting up four firms in the pyramid to control listed firms. Control, or voting, rights of ultimate shareholders (V) is 42% on average. The degree of separation of cash flow rights from voting rights is not great; the average CV is 0.86 and the median is 1, which means that among most listed firms in China, voting rights do not deviate much from cash flow rights and ultimate shareholders do not control firms with very low cash flow. Management ownership in listed firms is very low, only about 0.03%, which means that management in China is not provided with enough stock incentives. Outside directors make up less than one third of total directors on boards, which is close to the minimum standard (one third) required by the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC), and indicates that listed firms do not have many incentives to appoint outside directors, with most simply complying with the requirement. This situation may lead to the ineffectiveness of outside directors. Directors who are also management comprise about 20% of all directors, which means that 2 out of 5 directors also participate in the daily operation of firms; therefore, they can convey more information to other directors about firm operations, which increases the efficiency of information communication and decision-making processes. However, this may also lead to the insider control problem. In 10% of the sample firms, the CEO is also the chairman, which may lead to selfmonitoring problems.

Cash flow from operations to total assets is 0.059 on average, and firms show high growth, with a 19.77% growth in revenue. However, about 15.74% of the sample firms suffer losses during the sample period.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics

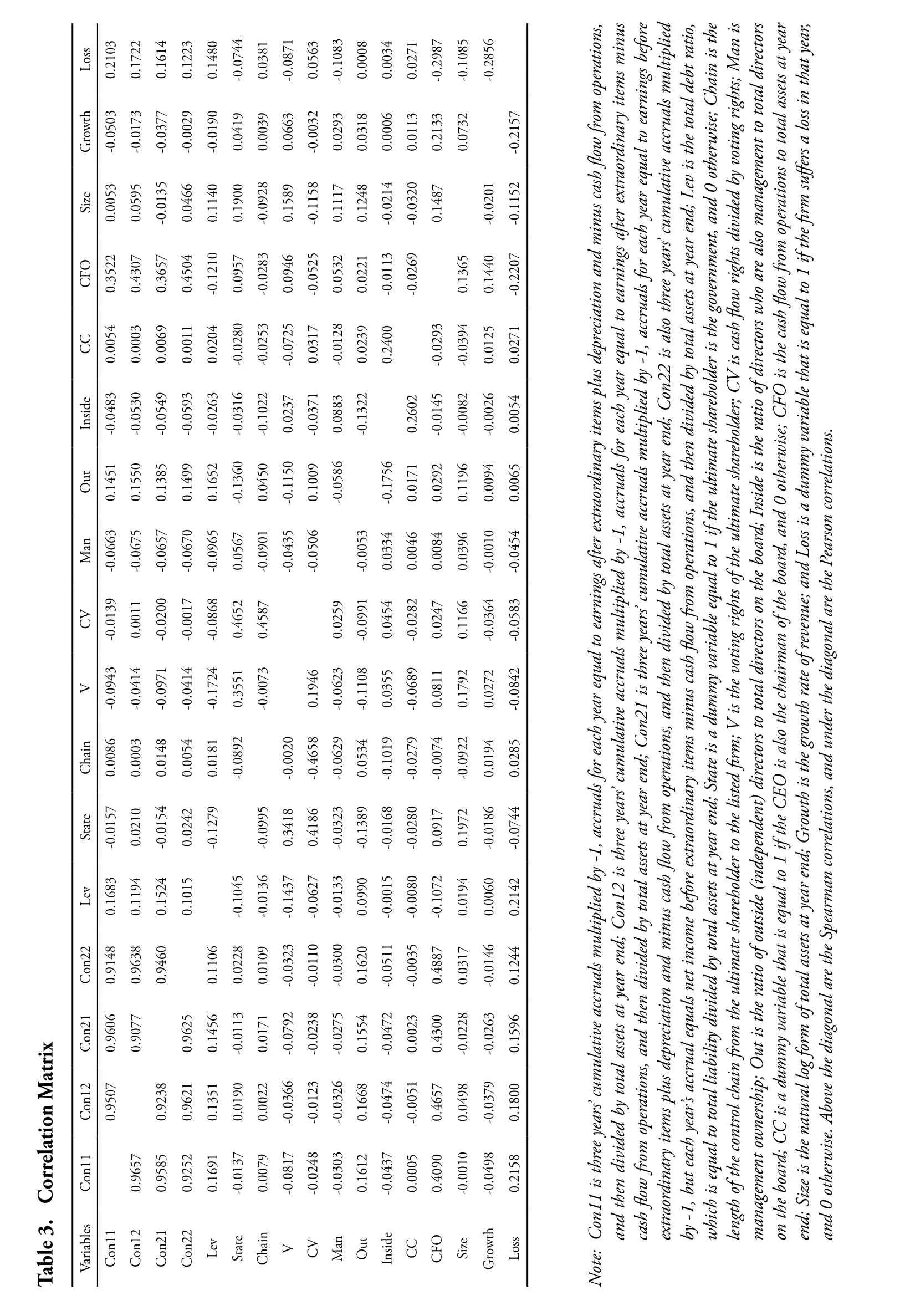

Table 3 shows the correlation coefficients for the variables. They are 0.4658 for CV and Chain and 0.4186 for CV and State, which is natural in a pyramidal structure, as a greater number of layers often lead to greater separation of control from cash flow rights. Among firms controlled by the government, the degree of divergence is much less. The coefficients indicate that collinearity is not a significant problem.29In the regression model, we test the VIF, variance inflation factor, to check for the collinearity.

?

5.2. Regression Analysis

Table 4 shows the regression results for the determinants of conservatism based on the cumulative accruals using the data of Chinese listed firms. We perform the regression using the four measurements of conservatism. As conservatism is very stable across years (see Table 1), we cluster the standard errors by year (Peterson, 2008) and add year dummies to control for year effects.

Table 4. Information Asymmetry, Agency Problems and Accounting Conservatism

Because creditors are at an information disadvantage, to protect their interests they will demand conservative financial reporting. The greater is their interest in the firm, the greater is the loss that they may suffer in the future and thus the greater will be the pressure that they will exert on management for conservative accounting. Because more conservative accounting can decrease the level of unnecessary losses and financing costs, it is also beneficial for management and controlling shareholders; thus, they will have incentives to adopt conservative accounting practices. The results in Table 4 show that after controlling for the influence of ownership structure, management/board and other fundamentals, Lev is positively related with accounting conservatism and significant at the 0.01 level for all four regressions, which means that greater debt imposes more pressure on management to adopt a conservative financial reporting policy, which leads to greater accounting conservatism. Hence, Hypothesis 1 is supported.

The significantly positive coefficients for State reveal that the level of accounting conservatism among SOEs is higher than that among non-SOEs; hence, Hypothesis 2 is supported. Although in SOEs it may appear that no principal is in charge, the pressures and constraints that the management of these firms deal with are much greater than those with which the management of non-SOEs must contend. SOE managers face greater political pressure, and hence their political costs are higher than those of their non-SOE counterparts. Non-SOE management or individual ultimate shareholders also face fewer government-related constraints. Therefore, the incentive to comply with accounting principles is greater among SOEs than among non-SOEs.

As the number of layers in the corporate pyramid increases, so does the level of information asymmetry, and investors will demand a higher level of accounting conservatism. Although information asymmetry may lead to greater agency costs,motivating management or ultimate shareholders to exaggerate earnings and tunnel via aggressive reporting policies, the final result will be determined by the equilibrium between the supply and the demand sides, which will have different financial reporting policies. We find that the influence of the pyramidal structure on conservatism is positive in general, especially among non-SOEs, indicated by the positive relation between Chain and the conservatism measures; hence, Hypothesis 3a is supported. This result also shows that the effect of the demand side is greater than that of the supply side. Among SOEs with a longer chain of control, the level of government interference is lower; therefore, the pressure to comply with accounting principles is reduced, as shown in the negative coefficient for StateChain, which is significant at the 0.05 level. Hence, Hypothesis 3b is supported.

As the level of control/voting rights increases, controlling shareholders rely less on accounting information, which leads to a decrease in the level of accounting conservatism. Such an increase in voting rights can lead to the expropriation of the wealth of small investors by ultimate shareholders and worsen agency problems (Jensen and Meckling, 1976; Watts and Zimmerman, 1986); accounting information is more likely to be manipulated and there is less incentive for conservative reporting. The regression results show significant negative coefficients for V in all regressions; thus, hypothesis 4a is supported. However, the coefficient for the separation of voting rights from cash flow rights is positive but not significant, and thus hypothesis 4b is not supported. One possible explanation for this finding is that the degree of such separation is not great in China, and the tunneling incentive on average may not be significant. Another possible reason may be that the demand is not greater than the supply.

Management will manipulate earnings by choosing a reporting method that will maximize their own interests. This will lead to less conservative annual reports, especially when the level of management ownership is higher and compensation is more closely linked with firm performance. This is shown by the negative relation between Man and the conservatism proxy, which is significant at the 0.10 level. Thus, Hypothesis 5 is supported.

The motive in China for introducing the mechanism of outside directors is to ensure greater corporate board independence and protection of investor interests. A higher outside director ratio indicates a higher level of board independence, and thus better protection of the interests of creditors and small investors. However, in China, outside directors do not play this role, as authorities and small investors might expect. A conservative accounting policy is found to be negatively related to the ratio of outside directors, which is inconsistent with our expectations and the findings for the United States market (Ahmed and Duellman, 2007). One possible explanation for this finding is that independent directors in China are often ‘vases’30This means the independent directors cannot voice for the minority shareholders; what they do is to agree with whatever the management or larger shareholders want.and do notwork as efficiently as expected. Accounting reporting policies are controlled by large shareholders or management: what outsider directors are required to do is to vote on and confirm that reporting. A higher percentage of outside directors may give management or large shareholders more power on the board and greater opportunity to manipulate accounting information. Management on boards, defined as inside directors, may adopt aggressive accounting policies to maximize their own interests in theory; however, the coefficient for Inside is only significant in the regression for Con21. Separation of the CEO and chairman roles does not significantly influence accounting conservatism, either. Regression analysis shows that the influence of the board on accounting conservatism in China is not as great as that of ownership structure or debt; therefore, hypothesis 6 is not supported.

We should note that loss firms may tend to engage in earnings management by taking a “big bath” in the latter year, which could influence the conservatism measure.Therefore, we use a dummy variable (Loss) to control for this effect. Even though the coefficient for Loss is significantly positive, meaning that the measure of conservatism may be affected by the earnings management incentive and loss firms indeed will create more accruals, the coefficients for our variables of interest are still consistent with the hypothesis, meaning that earnings management does not change our results.

To investigate which determinant has the greatest effect on conservatism, we also run separate regressions for debt, ownership structure and board31For the sake of brevity, we do not report the regression results, which are consistent with the results in Table 4.; the R2for each one is 0.3473, 0.3121 and 0.3084, respectively, revealing that debt is the most important factor, followed by ownership, and that board has little influence.

5.3. Robustness Testing

Table 5 shows the results of robustness tests using the first conservatism measure (Con11).32The results for the other three conservatism measures are basically the same but are not reported here for the sake of brevity.

Note: Con11 is three years’ cumulative accruals multiplied by -1, accruals for each year equal to earnings after extraordinary items plus depreciation and minus cash flow from operations, and then divided by total assets at year end; Con12 is three years’ cumulative accruals multiplied by -1, accruals for each year equal to earnings after extraordinary items minus cash flow from operations, and then divided by total assets at year end; Con21 is three years’ cumulative accruals multiplied by -1, accruals for each year equal to earnings before extraordinary items plus depreciation and minus cash flow from operations, and then divided by total assets at year end; Con22 is also three years’ cumulative accruals multiplied by -1, but each year’s accrual equals net income before extraordinary items minus cash flow from operations, and then divided by total assets at year end; Lev is the total debt ratio, which is equal to total liability divided by total assets at year end; State is a dummy variable equal to 1 if the ultimate shareholder is the government, and 0 otherwise; Chain is the length of the control chain from the ultimate shareholder to the listed firm; V is the voting rights of the ultimate shareholder; CV is cash flow rights divided by voting rights; Man is management ownership; Out is the ratio of outside (independent) directors to total directors on the board; Inside is the ratio of directors who are also management to total directors on the board; CC is a dummy variable that is equal to 1 if the CEO is also the chairman of the board, and 0 otherwise; CFOis the cash flow from operations to total assets at year end; Size is the natural log form of total assets at year end; Growth is the growth rate of revenue; and Loss is a dummy variable that is equal to 1 if the firm suffers a loss in that year, and 0 otherwise. In the first four columns, in the parentheses are the clustered standard error statistics. In the fifth column, in the parentheses are the Newey-West modified for Fama-Macbeth standard error adjusted statistics, and in the last column, in the parentheses are the two-way clustered robust standard error statistics. ***, ** and * indicate significance at the 0.01, 0.05 and 0.10 levels, respectively.

Column 1 shows the regression results for the SOE sample, and column 2 those of the non-SOE sample, to further compare the differences between the two types of firms.The coefficient for Chain is not significant among SOEs, as the effect of the pyramidal structure on conservatism among SOEs is determined by the effect of reduced political cost and that of greater information asymmetry. Among non-SOEs, it is significantly positive, meaning that information asymmetry will require more conservative reporting. Regarding the control rights of ultimate shareholders, the greater is their control, the lower is the level of the conservatism of their financial reporting, indicating less demand for accounting conservatism. The separation of control rights from cash flow rights still does not significantly influence the financial reporting policies of either SOEs or non-SOEs. The coefficient for management ownership (Man) is not significant among non-SOEs but still negatively significant among SOEs. This may be related to the influence of ultimate shareholders as individuals in non-SOEs, where management have greater authority and power, unlike the case in SOEs. For board independence, a greater number of outside directors in non-SOEs have a negative influence on conservative reporting, but the effect is not significant in SOEs. Also, among non-SOEs, the ratio of inside directors decreases the level of conservatism of financial reporting. This may be due to the reduced monitoring effect of the board, which is dominated by management (insiders); in such cases, management tend to adopt aggressive accounting reporting policies. Whether or not the CEO is also the chairman still does affect the financial reporting policy of either SOEs or non-SOEs. The results are basically consistent with those that we present in Table 4, and generally support our hypotheses.

The influence of the control rights of ultimate shareholders on the financial reporting policy may not be as linear as the influence of management ownership on firm value or performance. To test for the nonlinear relation, we use the square of control rights as arobustness test.33We also check for other nonlinear relations, such as three squares or four squares, and the results are basically the same, which means that the nonlinear relation is not supported.The results, which are shown in column 3, reveal that the coefficient for V-sq (the square form of control rights) is insignificant, meaning that a nonlinear relation is not supported. The coefficient for V is still negative and significant at the 0.05 level. The results for the other variables are consistent with those presented in Table 4.

Although operating liability, such as payments to suppliers or employees, is similar to debt from banks, the former may not play a role in the requirement for conservative reporting.34Creditors also demand conservative financial reporting; however, demand by creditors may not be as great as that by banks or other financial institutions.Thus, we use debt from institutions to substitute for total debt as a robustness test for the influence of debt. Debt from institutions is measured by shortterm debt from banks plus long-term debt from banks plus the bond payable scaled by total assets at year end. The results, which are presented in column 4, show that the coefficient for the new leverage variable indicates again a positive relation with conservatism and is significant at the 0.01 level, consistent with the results for total debt. Concerning the explanatory power of total debt (R2= 0.3522) and debt from institutions (R2= 0.3338), we can say that other creditors may also have some influence on the level of conservatism of accounting reporting.

Accounting studies increasingly rely on panel data, which are cross-sectionally and serially dependent; however, the econometric literature shows that two-way cluster robust standard errors (CL-2) are robust to both cross-sectional and time-series correlation (Petersen, 2008). To demonstrate the appropriateness of our model, we show in Table 5 the results using other regression methods: the Newey-West modified for Fama-Macbeth and CL-2. The results do not change.

6. Conclusion

A principal-agent relation exists among creditors, shareholders and management (Jensen and Meckling, 1976), and information asymmetry among them leads to asymmetric loss functions, which induces conservative accounting (LaFond and Watts, 2008). This paper investigates the determinants of accounting conservatism using accrual-based measures and data from 2001 to 2006 in China. We find that a high degree of leverage, low level of control of ultimate shareholders, and low level of management ownership lead to conservative reporting. We provide evidence in support of the argument put forward by Ball et al. (2003), namely, that management incentives to comply with standards significantly influence the level of the conservatism of accounting reporting and information quality. Non-SOEs and SOEs in China have different political concerns and are subjected to different pressures, which leads to different levels of conservatism in their financial reporting. A reduction in thoseconcerns and pressures leads to a corresponding decrease in accounting conservatism. Our findings reveal that board independence has no effect on the level of accounting conservatism.

A number of issues remain unresolved. The first is the endogeneity problem, which is always a concern in corporate governance and often ignored in the conservative accounting research. In this paper we do not solve this problem. Because the determinants of conservatism in our paper cover four aspects, it is very dif ficult to deal with the problem of endogeneity. The second issue is that our data comes from before 2007, in which year the CSRC initiated new accounting principles based on the concept of fair market value. How this concept influences conservative accounting compared with traditional cost accounting is not addressed in this paper.

Ahmed, A. S., Billings, B. K., Morton, R. M., Stanford-Harris, M., 2002. The role of accounting conservatism in mitigating bondholder-shareholder conflicts over dividend policy and in reducing debt costs. The Accounting Review 77 (4), 867-890.

Ahmed, A. S., Duellman, S., 2007. Accounting conservatism and board of director characteristics: An empirical analysis. Journal of Accounting and Economics 43, 411-437.

Ball, R., Kothari, S. P., Robin, A., 2000. The effect of international institutional factors on properties of accounting earnings. Journal of Accounting and Economics 29, 1-51.

Ball, R., Robin, A., Wu, J., 2003. Incentives vs. standards: Properties of accounting income in four East Asian countries. Journal of Accounting and Economics 36, 235-270.

Ball, R., Shivakumar, L., 2005. Earnings quality in U.K. private firms. Journal of Accounting and Economics 39 (1), 83-129.

Basu, S., 1997. The conservatism principle and the asymmetric timeliness of earnings. Journal of Accounting and Economics 24, 3-37.

Basu, S., 2009. Conservatism research: Historical development and future prospects. China Journal of Accounting Research 2, 1-20.

Beaver, W., Ryan, S., 2000. Biases and lags in book value and their effects on the ability of the book-tomarket ratio to predict book return on equity. Journal of Accounting Research 38, 127-148.

Beaver, W., Ryan, S., 2005. Conditional and unconditional conservatism: Concepts and modeling. Review of Accounting Studies 10, 269-309.

Beekes, W., Pope, P., Young, S., 2004. The link between earnings timeliness, earnings conservatism and board composition: Evidence from the U.K. corporate governance 12, 47-59.

Bushman, R., Piotroski, J., 2006. Financial reporting incentives for conservative accounting: the influence of legal and political institutions. Journal of Accounting and Economics 42, 107-148.

Chandra, U., Wasley, C., Waymire, G., 2004. Income conservatism in the U.S. technology sector. Financial Research and Policy Working Paper No. FR 04-01. Working Paper, University of Rochester.

Chen, S., Gul, F. A., Wu, D., 2008. Changes in accounting standards, ownership structures and conservative financial reporting in China. Working Paper, Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

Chen, H., Chen, J. Z., Lobo, G. J., Wang, Y., 2008. The effects of borrower and lender ownership type on accounting conservatism: Evidence from China. Working Paper, University of Houston and Xiamen University.

Claessens, S., Djankov, S., Lang, L., 2000. The separation of ownership and control in East Asian corporations. Journal of Financial Economics 58, 81-112.

Dietrich, J. R., Muller, K. A., Riedl, E. J., 2006. Asymmetric timeliness tests of accounting conservatism. Working Paper, Ohio State University.

Fan, J. P. H., Wong, T. J., 2002. Corporate ownership structure and the informativeness of accounting earnings. Journal of Accounting and Economics 33, 401-425.

Fan, J. P. H., Wong, T. J., Zhang, T., 2005. The emergence of corporate pyramids in China. Working Paper, Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Feltham, G., Ohlson, J. A., 1995. Valuation and clean surplus accounting for operating and financial activities. Contemporary Accounting Research 11, 689-731.

Francis, J., LaFond, R., Olsson, P., Schipper, K., 2004. Costs of equity and earnings attributes. The Accounting Review 79, 967-1010.

Givoly, D., Hayn, C., 2000. The changing time-series properties of earnings, cash flows and accruals: Has financial accounting become more conservative? Journal of Accounting and Economics 29, 287-320.

Gregoriou, A., Skerratt, L., 2007. Does the Basu model really measure the conservatism of earnings? Working Paper, Brunel Business School.

Holthausen, R. W., Watts, R. L., 2001. The relevance of value-relevance literature for financial accounting standard setting. Journal of Accounting and Economics 31, 3-75.

Holthausen, R. W., 2003. Testing the relative power of accounting standard versus incentives and other institutional features to influence the outcome of financial reporting in an international setting. Journal of Accounting Economics 36, 271-283.

Huijgen, C. A., Lubberink, M. J. P., 2003. Earnings conservatism, litigation, and contracting: the case of cross-listed firms. Working Paper, University of Groningen and Lancaster University.

Jensen, M., Meckling, W., 1976. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs, and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics 3, 305-360.

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes F., Shleifer, A., 1999. Corporate ownership around the world. Journal of Finance 54, 471-518.

LaFond, R., Roychowdhury, S., 2006. The implications of agency problems between managers and shareholders for the relation between managerial ownership and accounting conservatism. Working Paper, Barclays-Barclays Global Investors and Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

LaFond, R., Watts, R., 2008. The information role of conservatism. The Accounting Review 83, 447-478.

Lim, R., 2006. The relation between corporate governance and accounting conservatism: Australian evidence. Working Paper, Australian School of Business.

Lubberink, M. J. P., Huijgen, C. A., 2006. Cross-listing in US markets and conservatism: Does type of listing matter? Working Paper, Lancaster University and University of Groningen.

Nikolaev, V., 2006. Debt contract restrictiveness and timely loss recognition. Working Paper, Tilburg University.

Penman, S. H., Zhang, X. J., 2002. Accounting conservatism, the quality of earnings, and stock returns.The Accounting Review 77 (2), 237-264.

Petersen, M. A., 2008. Estimating standard errors in finance panel data sets: Comparing approaches. Review of Financial Studies 22, 435-480.

Qiang, X., 2007. The effects of contracting, litigation, regulation and tax costs on conditional and unconditional conservatism: Cross-sectional evidence at the firm level. The Accounting Review 82, 759-796.

Qu, X., Qiu, Y., 2007. Mandatory accounting standard change and accounting conservatism- Evidence from the SHEX and SZEX. China Accounting Research 7, 20-28.

Richardson, G., Tinaikar, S., 2004. Accounting based valuation models: What have we learned? Accounting and Finance 44, 223-255.

Watts, R. L., 2003a. Conservatism in accounting part I: Explanations and implications. Accounting Horizons 17, 207-221.

Watts, R. L., 2003b. Conservatism in accounting part II: Evidence and research opportunities. Accounting Horizons 17, 287-301.

Watts, R. L., Zimmerman, J. L., 1986. Positive accounting theory. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Zhang, X., 2000. Conservative accounting and equity valuation. Journal of Accounting and Economics 29, 125-149.

Zhang, J., 2008. The contracting benefits of accounting conservatism to lenders and borrowers. Journal of Accounting and Economics 45, 27-54.

Zhu, S., 2006. The characteristics of ultimate shareholders and informativeness of accounting earnings. China Accounting and Finance Review 3, 1-30.

* We thank George Yang from Chinese University of Hong Kong and participants at CJAR Summer Research Workshop for helpful comments. We express our sincere appreciation to the anonymous referee and the English editor. This paper is sponsored by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 70772017).

** Corresponding author. Song Zhu: E-mail address: zhusong@bnu.edu.cn. Correspondence address: School of Economics and Business Administration, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, China, 100875. Donglin Xia: E-mail address: xiadl@sem.tsinghua.edu.cn. School of Economics and Management, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China, 100084.

China Journal of Accounting Research2009年2期

China Journal of Accounting Research2009年2期

- China Journal of Accounting Research的其它文章

- Institutional Environment, Blockholder Characteristics and Ownership Concentration in China*

- China-Related Research in Auditing: A Review and Directions for Future Research*

- Trade Credit, Future Earnings, and Stock Returns: A Self-Dealing Perspective*

- Performance Volatility and Wage Elasticity: An Examination of Listed Chinese A-share Enterprises*