The Art of Womanhood

By HUO JIANYING

GUAN Zhong (c. 725-645 B.C.), a prominent politician, reformer, and prime minister of the State of Qi during the Spring and Autumn Period (770-476 B.C.), clearly defined the traditional social division of labor between men and women 2,600 years ago: “A farmer has a constant task, and a woman has a constant chore; if a farmer does not farm, there will be people of hunger as a consequence, and if a woman does not weave, there will be people who have no clothes to keep themselves warm.” This division of labor addressed basic human needs and sustained the agricultural society of feudal China for thousands of years, providing the basis from which Chinese culture and Confucianism developed.

In the early days of the “men farming and women weaving” society, the products of womens weaving and collateral activities were referred to as “the work of womanhood,” or “nügong” in Chinese. Later the character “gong,” meaning “work,” was replaced by a more refined homonym that refers to feminine art. The “art of womanhood” encompasses an expanded social connotation of womanhood, from the basic domestic skills required of the gender for human survival, to the moral, temperamental and artistic qualities required by a more sophisticated society.

Inspiration from an

Ancient Painting

Pestling Cloth is painted by Tang Dynasty (618-907) court artist Zhang Xuan, who excelled at depicting women. Many of Zhangs works reflect the lives of female aristocrats, including this one. It depicts one of the daily jobs that constituted “womens work” 1,300 years ago. Pestling was a finishing process in weaving. When silk, linen or cotton cloth came fresh from handlooms it was stiff and needed boiling, bleaching, pestling and ironing before it was ready for making clothes.

There are 12 women in the painting. Judging from their nice clothes and healthy looks, they are court ladies, or women from well-off families. They form a team performing three processes. There are four in the pestling group; two are pounding hard, while the other two look as if they are catching their breath. The central section has two women; one is sorting threads, and the other is sewing. There are six women in the ironing group; one is tending a charcoal fire, three are stretching out a piece of cloth as one is ironing it, while a little girl is frolicking around.

However, such a division of labor was not common among ordinary families, for it required a sizable workspace and multiple hands. Usually housewives performed the work independently and preferred after-tailor pestling, as pestling clothes was much easier to handle by one person when working in a cramped space. They made clothes and did pestling for their family in the evening, while taking care of their children and performing other domestic chores during the day. A line from Li Bai, a great poet of the Tang Dynasty, records the lives of the time: “When moonlight spreads over Changan, the sound of pestling clothes arises from thousands of families.”

In fact, making clothes was not only a family duty of women, but also their social responsibility. They sewed winter clothes for their sons, brothers, or husbands who had been recruited into military service, and supplied military uniforms to the state as taxes and levies in kind.

Imperial and aristocratic families were no exception, as farming and textiles were foremost priorities of the ruling class. Starting from the Zhou Dynasty 3,000 years ago, royal women raised silkworms and made silk fabrics and clothes. The empress, as the supreme model of womanhood, played a leading role in the job, in order to encourage all the womenfolk to fulfill their expected role.

This tradition was carried into the Tang Dynasty, when imperial women — court maids and emperors wives as well — made winter clothes for frontier soldiers as part of their daily work. During the Kaiyuan Reign in the early eighth century, Emperor Xuanzong sent a batch of winter clothes made by the imperial family to a frontier garrison as a token of imperial benevolence. One soldier found a poem in the cotton-padded robe he received. It expressed the feminine sentiment of a young woman for a man whom she did not know but for whom she had sewed clothes with all her tender heart. It concludes with the line: “This life we pass as strangers, may fate unite us in the next life.”

The soldier dared not conceal the matter, since all court maids were theoretically the emperors women, and turned the poem in to his commander, who forwarded it to Emperor Xuanzong. The emperor displayed the poem in the court and promised he would not punish the writer if she came forward. A court maid admitted to composing and sending the poem and asked for the emperors punishment. Kind-hearted Xuanzong married the maid to the solider who received her poem, saying that he wanted them to be united in this life. When the story reached the frontier garrison, all the soldiers were deeply moved. This poem was later included in The Complete Collection of Tang Dynasty Poetry (Quan Tang Shi, compiled in 1706 on the orders of Qing Emperor Kangxi). It was titled Poem in the Robe, and its writer was identified as “a court maid of the Kaiyuan Reign.”

The Birth of Feminine Art

Ancient China put the desirable qualities of womanhood into four categories: morality, manner of talk, manner of behavior, and craft skills (or the work of womanhood). They were collectively known as the “Four Virtues.” Initially they were compulsory lessons that all the imperial and aristocratic women had to learn and observe, but later they seeped into the ordinary family life of all women, rich and poor. As one aspect of sublime womanhood, craft skills were enhanced throughout the centuries of imperial China not only as a means of livelihood, but also a yardstick by which to measure a womans personality and cultivation.

As womens craft skills improved, their products gained increasing artistic and aesthetic qualities, and “nügong as work” was gradually replaced by “nügong as art.” Girls in ancient times began to learn “the art of nügong” from a very young age. Nü Er Jing (The Classic for Girls), a three-character rhymed folk text whose origin can be traced back to no later than the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), advises that girls should retreat into their rooms to do needlework after getting washed in the morning, and that they became adult at the age of 11, when they should help cook for the family and spend the rest of the day in their room doing needlework.

With the help of her mother, an unmarried young woman would do needlework year after year to fill her dowry closet, which included not only her own clothes and articles of daily use but also items for her future husband, in-laws and children. Matchmakers usually presented carefully selected samples of girls needlework to show the excellence of their womanhood to their prospective in-laws, since a skilled daughter-in-law would bring the family great honor.

As “nügong” developed into a genre of art, its products diversified and expanded to include various aspects of the feminine workmanship, such as weaving, dying, sewing, embroidery, knitting, paper-cutting, and cloth patchwork. The most widely applied and exemplary of these arts was embroidery.

Masterpieces of Womanhood

Embroidery has a long history in China. Unearthed artifacts dating back more than 2,000 years speak of the highly developed craftsmanship of ancient times, as demonstrated by the elegant, curvilinear patterns done in fine and meticulous stitches of harmonious colors.

By the Song Dynasty around 1,000 years ago, stitchwork had become even more delicate and subtle, as evidenced by the following description: “Tiny and dense stitches are arrayed to close up their edges, their thread being composed of one or two silk fibers and the needle used is hair-thin.” Such works of subtlety gradually emerged from embroidery done for daily use to become a highbrow ornamental art. However, these fine works were small in number. The majority of embroidered items were still folk products for daily use, done by ordinary housewives and girls.

Folk embroideries include garments, articles of daily use (such as tablecloths and bedding), and dowry and ritual items. Garments and accessories were the largest category, particularly for women and children. Embroidered patterns included auspicious animals, birds and flowers and other images that connoted happiness, fortune, peace and longevity. There were also motifs taken from folk tales and theatrical products.

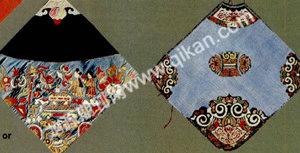

Embroidered “dudou” (belly aprons) are worth a special mention as a characteristic Chinese underwear for children and adults alike. Traditional Chinese health theory believes the belly to be the most vulnerable part of the human body in terms of cold, so it needs extra protection. The aprons are diamond- or square-shaped, and have a looped lace to drape around the neck, and two laces to tie behind the waist. Those for brides are red in color, and are embroidered with patterns of lotuses, peonies, phoenixes or mandarin ducks.

A great deal of embroidery effort was also taken with pillows, as people spent more or less one-third of each day lying on them. Ancient pillows were rectangular-, or tube-shaped, their ends enclosed by square or round embroidered covers called pillow ends. Girls needed to embroider many pillow ends as part of their dowry, which would be displayed in their wedding chamber to demonstrate their fine “womanhood.” There were also embroidered ear pillows — cushions with a hole in the center to accommodate the ear when one sleeps sideways.

Embroidery is widely practiced by women of minority ethnic groups as well. Miao girls start to learn embroidery with their mother at the age of four or five, and their works are mostly improvised without following any preset design. The embroidery of the Tu people on the Qinghai Plateau is also representative of an ethnic exotic “womanhood.”