Journeys Across China:An American in Tibet

ETHEL LU

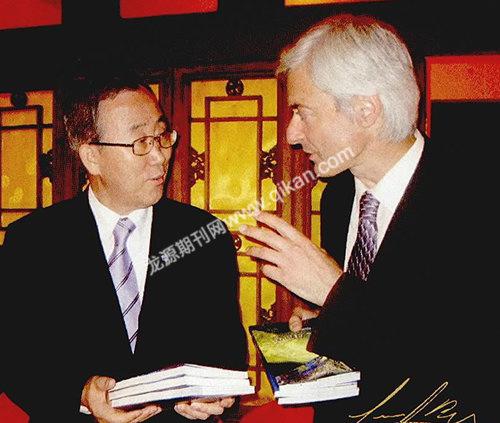

LAURENCE J. Brahm spent five years completing his Tibetan trilogy— Searching for Shangri-la, Conversations with Sacred Mountains and Shambhala — and so it was with a deserved sense of accomplishment that he presented finished copies in July to his old friend Ban Ki-moon, secretary general of the United Nations, then on an official visit to Beijing.

By all accounts, Ban Ki-moon was delighted with the gift, telling the author that his descriptions of Chinas cultural diveristy and the emerging environmental consciousness of its people beautifully reflected the United Nations own Millennium Development Goals. Travelling throughout western China, including Tibet, Qinghai, Yunnan, and Sichuan, Brahm met hundreds of compelling people and witnessed some of the worlds most extraordinary natural vistas, emerging with stories that have received unanimous praise from critics and readers alike for their color and vibrancy.

From Investment Consultant to Spiritual Wanderer

Laurence, an American by birth, first arrived in China more than 20 years ago to work as a lawyer and political economist. He provided consulting services for international corporations planning to invest on the mainland, and over the years he published a number of economically oriented books about China and Asia, such as Chinas Century, Zhu Rongji and the Transformation of Modern China, and China as No. 1.

But whenever he was asked for the deeper reason that had brought him to China, he was at a loss for a reply. “I havent found the answer, even now,” he says. And he was growing tired of advising people only interested in making a fortune in Chinas booming post-reform economy. It was a life he had grown to know only too well, but it was also one that would change dramatically after waking from a dream in which he saw wild horses galloping across the Tibetan steppe. Taking his vision as a sign, he resolved to see those horses for himself, and in 2002 he quit his job in Beijing to become an independent media producer. The next stop was Tibet.

The stories he heard on that first trip fascinated him and got him thinking. While in Lhasa, Brahm paid a visit to a studio created by a local artist, Nangsang, who designed Tibetan costumes and patterns for a local handiworks factory. That factory, set up by a lama, provided a livelihood for some 50 handicapped workers while supporting 100-plus orphans.

The lama, Jigme Gyaltsen, lived in a remote village in Qinghai, where he produced cheese from yak milk brought to him fresh daily by local herdsmen. The resulting income helped the villagers thrive, but more importantly, allowed them to preserve their traditional lifestyle. With the proceeds, he was also able to establish a school where children study free-of-charge, and where they have ready access to the Internet.

Continuing his travels in Yunnan, Brahm visited Kunming, Dali, Lijiang, Lugu, Zhongdian (renamed Shangrila in 2001) and Meili Snow Mountain, popular destinations with tourists from around the world, and it was there that he observed a disturbing trend in the gradual decline of minority ethnic cultures. But he also met a number of resilient people fighting to maintain their cultural identities against the incoming tide of modernization.

The most impressive, he says, was Yang Liping, a celebrated dancer in China. Her powerful yet graceful dancing has moved countless audiences, allowing them to discover the cultural legacy of Yunnans minority communities. Brahm later met the diminutive dancer in the provincial capital Kunming, where Yang had set up her own studio after giving up her position with the China National Ethnic Song and Dance Ensemble in Beijing. These days, she welcomes young people from some of the provinces most remote villages, capturing their songs and dances on film in order to preserve them for posterity.

In Searching for Shangri-la, Brahm said he wanted to find the Shangri-la James Hilton described in his 1933 novel Lost Horizon. There is a county called Shangrila in Yunnan, but many other places have also staked their claim to being the legendary city, in part for commercial reasons. After searching long and hard, Brahm concluded that Shangri-la was not an actual place, but a state of mind, an idea and a lifestyle.

“Many places claim to be Shangri-la, like Lijiang and Zhongdian, and even some towns in Tibet and Sichuan,” he was once told by a local. “Actually, you will find it everywhere on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, in every leaf. I think it is only a concept — natural and peaceful, just like heaven.” Brahms books have captured that ideal.

A Visit to Shambhala

One day, Brahm bought himself an ancient Buddhist sutra, Sutra of Shambhala, in a small antique shop, and immediately set off in search of the mysterious land. Guided by the sutra, he traveled into the forbidding wilderness of western Tibet, sharing conversations along the way with lamas, living Buddhas, and herdsmen about their personal understanding of the mythic Shambhala, arriving eventually at the Tashilhunpo Monastery, home to the Eleventh Panchen, Erdeni Qiogyi Gyibo.

His book Shambhala records a conversation he had with the 15-year-old Panchen. When he humbly asked how to reach Shambhala, he was told that the concept originated in ancient India, the birthplace of Buddha, and that people regard it as a pure land of harmony, where the king wields the power of good to remedy the sins wrought by evil. There, the Panchen told him, the resulting spiritual serenity allows people to enjoy health and longevity, and to live in peace and harmony.

While in Tibet, Brahm also came across pilgrims from all over the world, and from all walks of life, who had chosen to withdraw from their ordinary routines and settle down in Lhasa or Lijiang to live out Tibets sacred traditions. Brahms meticulously describes them all in his books.

The trilogys publisher, New World Press, has now released the three volumes in both Chinese and English, with a bonus DVD attached based on the photographs the author took over his five-year journey, and readers can discover for themselves the mysteries and charms of that enchanted land.

As for his future plans, Brahm says he has established two studios,Xinhong-zi and Shambhala, aimed at protecting cultural diversity and the sustainable development of cultural projects. UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon, for one, would most certainly approve.

- CHINA TODAY的其它文章

- BASIC CHINESE FOR THE BEIJING 2008 OLYMPIC GAMES

- Discover the Han Heritage in Xuzhou

- Seventy Years Later,James Hilton’s Shangri-la Rediscovered

- Innovation and Excellence:Tianjin University of Finance and Economics

- The Development of an Agricultural City

- The Pig Breeding Industry Benefits Anhui Farmers