Thirty Years of Chinese Contemporary Art

staff reporter ZHANG XUEYING

IN 2007, Chinese artists held a number of retrospective exhibitions, such as the Retrospective Exhibition of the No Name Group (1979), the Exhibition of 1985 Avant-garde Fine Art, the Retrospective Exhibition of the Star Art Group of 30 Years Ago, and the Exhibition of the Qingdao Dream of Modern Artists in the 1980s. Thirty years ago, however, many of the works now openly displayed were exhibited unofficially, and some were even banned by the government.

Conventional wisdom holds that Chinas contemporary art can be divided into four periods – the first being the post-“cultural revolution” period of 1976-1984, the second lasting from 1985 to 1989, the third from 1990 to 1999, and the fourth from 1999 to the present.

Awakening

The latter half of the 1970s is considered by many to be the most important period in modern Chinese history, culminating as it did with the end of the “cultural revolution” (1966-1976). Following that decade-long upheaval, China embarked on a policy of reform and engagement with the outside world, and set out to remedy the political errors of the past. Chinas central authorities instituted the principle of “seeking truth from facts,” and the new approach provided Chinese society with rich opportunities for development.

Artists were inspired to begin reflecting the realities of modern life, which required an unflinching observation of peoples ordinary lives. Yet, in the early 1980s, Chinese fine arts academies were still under the strict control of academic formalism, and the individuality of artists and the artistic depiction of individuality were discouraged.

At the same time, Chinas reforms and growing accessibility allowed Western modern art to be introduced. In 1979, the National Art Museum of China (NAMOC) held the Exhibition of 19th Century French Rural Landscapes. In the five years that followed, a number of Western modernist painting exhibitions were held in quick succession, such as the Painting Exhibition of Impressionist Art, the Exhibition of Original Oil Paintings from the Boston Art Gallery Collection, the Painting Exhibition of German Expressionism, and the Exhibition of Picassos Original Paintings. To young painters who knew only the works of the former Soviet Union, and Chinese audiences who for many decades could only view propaganda posters, the new scene was a breath of fresh air, and art lovers reveled in the new freedoms.

The works of many Western modern and post-modern philosophers and theorists, such as Friedrich Nietzsche and Jean-Paul Sartre, were translated into Chinese, and devoured by Chinese college students and young artists. Everyone seemed to be discussing culture, philosophy, and human nature. People joined book clubs to discuss works they had read.

Old photographs still offer a glimpse into those heady times. In keeping with their brethren throughout the world, young people wearing black-rimmed glasses, old-style cotton-padded jackets, Mao-style suits, vests, shorts, and rubber-soled shoes, would get together to discuss Nietzsche and Freud, Edvard Munch and Pablo Picasso, and to exchange picture albums and slides of works.

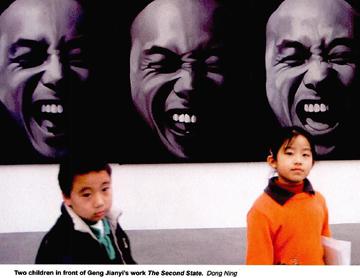

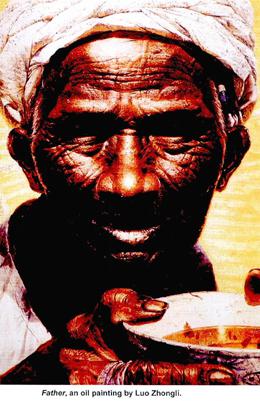

And as they discussed, they began to practice Western modern art. In 1980, an oil painting by Luo Zhongli, entitled Father, became the most famous representational work that year.

The painting depicted the wrinkled, weather-beaten face of an old peasant holding a broken bowl, and the water in the bowl is muddy and brackish. The painter applied natural color and photorealism from the United States to depict an ordinary, miserable old man in rural China, and in so doing overturned the dictums of the “cultural revolution,” which emphasized magnificence, happiness and positive themes.

One intriguing point is that when Luo Zhongli painted the work, the old peasant did not have a ball-point pen stuck behind his ear. According to an insider, Luo Zhonglis work was painted for an exhibition, but when he sent it to the gallery, a veteran artist advised him to add the pen to reflect the new image of Chinese farmers.

“At that time, the social background in China was social revolution and emancipation of the mind – that is, setting things right politically. When China opened its doors, we were faced with many new questions: poverty and prosperity, advancement and backwardness, new and old, which stood in stark contrast to one another,” according to Li Xianting, an art critic known as the “godfather of Chinese contemporary art.”

“Under those circumstances, it was felt, artists should reflect on society with a view to emancipating the mind and playing an active part in social and political changes. At the time, an important aspect of the work being done by young artists lay in their evident political criticism and their vision. They were at the forefront of the movement to free peoples minds. As a result, they were both rebellious and prophetic,” said Li.

The Star Art Exhibition held in Beijing in 1979 was regarded as the most radical and free-wheeling exhibition in Chinese art history in the 20th century.

On September 27, 1979, a number of sculptures displayed on a fence to the east of the National Art Museum of China attracted a crowd of viewers. More than 20 artists participated in the exhibition. Wang Keping, an important member of the Star Art Exhibition, exhibited 30 wood sculptures. One of them, entitled Silence, is regarded as the representative work of the event. It depicts a mans head, whose eyes are covered and whose mouth is sealed, an agonizing image of a man who cannot see and speak freely.

Another work of his, entitled Breathing, is composed of wood and plastic, and depicts a mans head whose nose and mouth are sealed by a plastic pipe. He has difficulty breathing and his eyes are bulging grotesquely.

Since that radical exhibition was seen as a threat to the social order, it was suspended three days after opening. But the artists of the Star Art Group did not compromise. They held a demonstration, holding high a banner reading “freedom of art.” To everyones surprise, after the demonstration the exhibition was allowed to continue, and it aroused even greater enthusiasm the following year. Their works were allowed to be displayed inside the National Art Museum of China, and once attracted a record-high 9,000 visitors in a single day.

Although doubts and arguments regarding the works of the Star Art Group have never completely died down, one thing is now beyond dispute – the role it played in promoting the development of Chinas contemporary art scene cannot be underestimated. Bao Pao, a well-known art critic, said, “The greatest significance of the Star Art Group is that it led to the awakening of intellectuals to the value of individual personality.”

Breakthrough

The environment for artistic and literary circles was relatively relaxed in 1985, but innovation and the breaking of all bonds was still the ultimate goal of Chinese artists.

At the International Peace Year Exhibition of Young Artists, a number of works not catering to political slogans, free from literary description, defying natural time and space, and applying multiple methods, went on display. These works made the viewers feel as if they were in the presence of something completely new, and the exhibition received widespread acclaim. The exhibitions far-reaching influence on the artistic creations of Chinese young people took the organizers by surprise.

In May 1985, at the Art Exhibition of Chinese Youth in Advancement, works featuring nudity and in Western modern art styles, such as The Inspiration of Adam and Eve in the New Era by Zhang Qun and Meng Luding, won prizes. That sent a clear signal that artistic freedom and intellectual liberty were at hand,and young artists, inspired by the development, began holding open exhibitions, while Chinese art circles buzzed with creative activity.

The most influential questions revolved around an artistic debate. In the July 1985 issue of Jiangsu Art Monthly Pictorial, an article entitled “My Views on Chinese Painting” by Li Xiaoshan, a post-graduate student of the Nanjing Art Academy, sparked a discussion as to “whether Chinese painting has come to a dead end.” It was the most actively engaged and participated in debate in the history of modern Chinese art. The controversy compelled people to re-examine the relationships between progress and tradition, and between the West and China.

Inspired by the spirit of freedom and innovation, many youth art groups appeared. According to statistics by Gao Minglu, a 1980s avant-garde artist, from 1985 to early 1987 about 90 art groups were established nationwide. They organized more than 150 group activities participated in by more than 2,000 artists. The more active groups included the “Northern Art Group,” the “Southwestern Art Research Group” of Sichuan Province, and the “Xiamen Dada” of Fujian Province. They were well known for their large number of artists and works, and the novelty of their concepts.

For a time a new tide of youth art surged high, culminating in the “85 New Tide.” Its dashing spirit and great vitality challenged old traditions, concepts, patterns and methods. In fact, the “85 New Tide” was not aimed at Chinese artistic tradition before the 19th century. Its starting point was against the mainstream artistic system.

Mao Xuhui, an important artist from the southwest in 1985, said, “We were really energetic, hot-blooded, regarding art as a means to realize individual freedom. At that time there was only one channel of expression in the art world, and there was only one voice to express an ideology. It was almost impossible for an artist to express his individual and independent voice within such a system.”

At that time, entries for national art exhibitions were selected through official channels. Mao Xuhui and other young artists sent their works to national art exhibitions several times, but were all rejected. That situation left them no choice but to rebel. Twenty years after the “85 New Tide,” people compared it to the European Renaissance, which was essentially a movement characterized by spiritual and artistic enlightenment, emanating from the new-born bourgeoisies struggle to win political status and rights.

In the early 1980s, Wang Guangyi, Gao Ming-lu, Xu Bing, Shu Qun and Zhang Xiaogang graduated from academies of fine arts and became the main protagonists of the 1985 Art Movement. Born in the 1950s, they were among the first group of art students since the restoration of university entrance examinations following the end of the “cultural revolution,” and had been more exposed than the general public to Western art. They deeply felt that China lagged behind Europe and America, and argued that it was the spiritual core of freedom and individuality, as reflected by Western modern art, that would serve as the cure for the spiritual malaise of the Chinese people.

“Between 1985 and 1989, we tried almost all the post-1960s art models of the West, and introduced all kinds of new language. The significance of this was that Chinese artists provided themselves with an opportunity to experiment with Western modern art in a comprehensive way,” said Xu Bing, an accomplished artist.

One incident in 1988 represented the overall social environment of China in that era. On January 1, the Tiananmen Rostrum, a symbol of power and history, was opened to the public for the first time. A forbidden space was turned into a tourist site. “That indicated that the mystery of the power system had been diluted a mere decade following Chinas proclamation ofeconomic reform in 1978,” said critic Li Xianting. An earthquake occurred in Chinas social structure as a result, and it led to an environment in which the repressed of the past began to speak out.

In February 1989, the “China/Avant-garde” Exhibition was held in the National Art Museum of China, an incident that must be mentioned in the history of Chinese contemporary art. The works on display by 186 artists included paintings, installations, performance, photographs and video, completely subverting the traditional Chinese approach to art.

Gao Minglu, one of the masterminds of the exhibition and now a professor at the Art Department of Pittsburgh University, said, “From the very beginning, I realized the importance of the National Art Museum of China. But I did not dare go there, since I knew they would not agree.” He added, “Only by entering the National Art Museum of China could the 85 Fine Art Movement emerge from the underground.” Gao Minglu spent more than six months persuading the curators of the NAMOC, and mobilized different ties to lobby the museum authorities. Finally, he obtained permission and the exhibition opened, but viewers were shocked by what they saw.

Artist Wu Shanzhuan sold prawns in the museum to subvert its official image, showing that it is also a venue of “big business.” More performance artists came without invitation. Li Shan washed his feet in a basin painted with multiple portraits of Ronald Reagan, and Wang Deren scattered condoms in front of almost all the works from the first to the third floors.

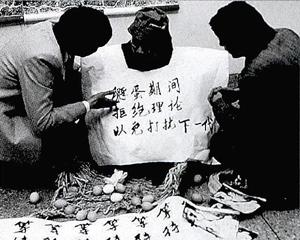

Two artists wrapped in white sheets entered the exhibition hall slowly, but were driven out by plainclothes policemen. In the exhibition hall on the second floor, Zhang Nian sat on the floor, wearing a small cap and draped in white paper, on which were written the following words, “During myincubation period, I refuse to debate, so as not to affect the next generation.” Around him were placed 18 eggs.

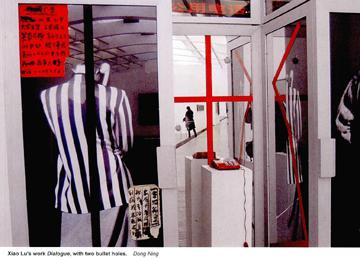

The most shocking incident occurred when artist Xiao Lu shot two bullets at her installation, entitled Dialogue. The police intervened, besieged the NAMOC, and the exhibition was suspended for four days. In 2001, Xiao Lu explained the thinking behind her act. “The others all had a strong sense of history, politics and mission, but I was perplexed by my personal emotions. I felt that this was my world.”

Li Xianting commented that Xiao Lus gunshots were an “answer to the curtain call for avant-garde art,” and that “Two gunshots pushed the ‘critical point of the avant-garde art a step forward. The ‘critical point is the limit that avant-garde artists are looking to impose – their new concepts and new modes – on society. That is a modern notion in itself, and also a unique phenomenon in Chinese contemporary art.”

At the Margins

“After 1989, the hope Chinese intellectuals had that Chinas problems could be solved by the modernism of the West completely evaporated. As a result, they began to observe Chinas problems in a down-to-earth way, especially regarding how the Chinese people lived. At that time, the living environment was in chaos. Old standards had been toppled, but new ones had not yet been established. During this period, everyone faced a broken spiritual world, and everyone was at a loss. Therefore, art in the early and mid-1990s was also under a similar cloud,” said Li Xianting.

A new trend was in vogue, and both the mindset and language had similarities – a sense of absurdity and ruffian-like humor, and a cynical realistic style – that is, political pop.

Similarly, the world of letters saw the birth of “ruffian literature” represented by writer Wang Shuo, and “new realistic literature” represented by Liu Zhenyun and Chi Li, that caught everyones attention. In music, it was the burgeoning of post-Cui Jian rock-and-roll groups.

Artists who became popular in the 1990s were mostly born in the 1960s. They graduated from university in the late 1980s, and their backgrounds and career paths greatly differed from past artists. They gave up the idealism and heroism of older generations, and the abstract philosophical constructs of the West that were commonly applied in the 1980s. They began to see life more broadly and to use personalized language to depict the world around them. Some used “ruffian” methods to describe themselves and the often meaningless, random and even absurd lives of those around them. Critics now maintain that this shift of perspective demonstrated the artists innate understanding of the Chinese peoples mentality at the time.

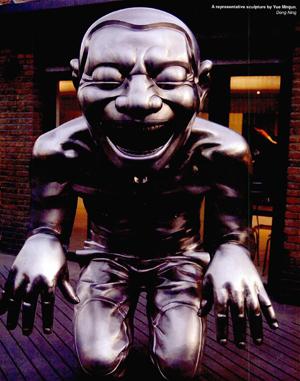

The representative works of the “Ruffians Group” mastered humor in two forms. First, they directly selected “absurd,” “meaningless” and “banal” life episodes; and second, they caricatured “serious” and “important” issues. For instance, Fang Lijun painted a portrait of his friend yawning, and created a unique charicature – a ruffian with a bald head.

The appearance of political pop was regarded as an important turn in the history of Chinese art. It demonstrated that the focus of artists had turned away from Western and other modern ideological trends to the realities of life as lived by ordinary Chinese. The appearance of political pop in the form of humor showed a trend away from political complexities, and signaled that modern Chinese art had set off down its own road.

A commensurate change took place in the lifestyles favored by artists.Yuanmingyuan Painters Village appeared at this time. Yuanmingyuan was the most magnificent imperial garden in China, known as the “best of 10,000 gardens.” In 1858, it was burned to the ground by the Anglo-French allied forces, and to this day the ruins are still seen as a reminder of a deeply humiliating period in contemporary Chinese history.

Starting in the 1990s, quite a number of artists from various regions of the country quit their official jobs and came to Beijing. They gathered nearYuanmingyuan in a brazen challenge to Chinas household registration and work unit system.

Yu Changjiang, a sociologist specializing in Chinas modern communities, said, “They converged there because they differed from mainstream ideals, habits and lifestyles. But although China had been carrying out its policy of reform and opening-up for over a decade, and in essence society had attained an unprecedented degree of pluralism, peoples tolerance of different lifestyles was still very low.”

By 1994, the Yuanmingyuan Painters Village was bustling and crowded. Most people never expected the community to produce so many accomplished artists: Ding Fang, Fang Lijun, Yue Mingjun, Yi Ling, Yang Shaobin, Xu Yihui and Chi Nai.

After becoming famous, Fang Lijun often recalled the days he spent in the Yuanmingyuan Painters Village, where he created works of a cynical style and won international recognition. In 1993, Fang Lijun participated in the Venice Biennale, and then his work appeared on the front page of the New York Times. Now he is no longer living in the “village.” He prefers to stay in his quiet studio. “Its too noisy there, because of money,” he said.

By the early 1990s, Chinas reforms had been ongoing for more than a decade, and coming together with artistic freedom was the market economy. “In the 1990s, we had more space, but many got stuck in the mire of consumerism,” said Fang Lijun. Artist Sun Pings performance art, entitled Renminbi A-Share of the Sun Ping Co., Ltd. of China, on display at the Guangzhou Biennale in 1992, is typical.

In the 1980s, self-employed businesspeople andtraveling salesmen became well-off ahead of others, and in the 1990s those who invested in the stock market became wealthy in even simpler ways.

Sun Ping chose share certificates at the 1992 Guangzhou Biennale as a symbolic expression of that ethic. The first paragraph of the introduction to the “company” reads, “This is the first privately owned enterprise in Chinese modern art that practices the industrialization of art. It has artists who are engaged in the research, development and production of high-grade, precision and advanced products of modern art, and who are fully capable ofpromotion and successful operating strategies.” The slogan has since been copied by many art companies and art galleries as their corporate mission statement.

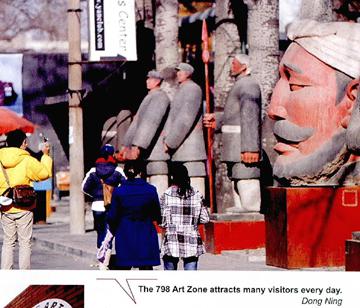

In the middle and late 1990s, artists began to combine art with commercial activities. The land price at Yuanmingyuan rose, and visitors increased day by day. Artists began to leave Yuanmingyuan Painters Village. After that, many more artist communities appeared, such as Songzhuang Art Center, 798 Art Zone, Shangyuan, Binhe Sub-district, and Feijiacun. Artists became professionalized, and a division between rich and poor occurred.

Prosperity and Shadow

Reform and openness, along with the gunshots at the exhibition of the National Art Museum of China, both attracted the Wests attention to Chinas contemporary art scene.

When art galleries were being founded by foreigners in China in the early 1990s, such as the Red Gate Gallery in Beijing and the Shanghart Gallery in Shanghai, Chinas modern art market was still an uncultivated wilderness. After efforts lasting about a decade, they began to reap the rewards as collecting and investing in modern Chinese art began to grow on the international market.

In the 21st century, modern art continues to expand rapidly – a prosperity that shows in four aspects. First, exhibitions are held frequently. Second, business in art galleries is brisk. Commercial galleries develop rapidly and non-commercial galleries rise and fall frequently. Third, capital pours in. A large quantity of international capital and investment capital is entering art operations and collections. Fourth, auctions are extraordinarily active.

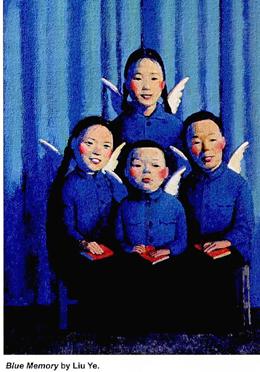

The evening sale of the Poly auction 2007 broke all records at a Chinese contemporary art auction: Zeng Fanzhis Mask No. 14 sold for RMB 8.8 million, eight times the appraised price. Zhang Xiaogangs Comrade Series: Men sold for RMB 1.76 million, a record high for his small-format works. Another work from the same series, entitled Women, sold for RMB 1.98 million, breaking the former record. The appraised price of Liu Yes work Big Flagship was RMB 1.2 million, but it sold for RMB 9.35 million. Mao Yans painting Memory or the Dancing Black Rose sold for RMB 9.845 million. And Shi Chongs Contemporary Scenery, which was used as the front cover of the auction catalogue, sold for RMB 16.5 million. Almost every art collector is nervous about the skyrocketing art auction prices.

The Modern Art Gallery jointly founded by Huang Liaoyuan and Zhang Haoming in September 2004 is located near the Beijing Workers Gymnasium. The gallery is new, but its business is brisk. At first, Huang Liaoyuan collected works by lesser-known artists, but soon the prices of these works rose by five times or more, challenging the works of better-known artists. Seven months after opening, the gallery turned a profit for the first time. “Our customers are the newly rich who have grown wealthy in the 30 years of reform and opening-up, rather than the international buyers who solicited us when we first started our gallery,” said Huang Liaoyuan.

However, the prosperity of Chinas contemporary art market has aroused concern. One is the worry expressed by foreigners, represented by the curator of the Paris Modern and Contemporary Art Museum, who said, “The development of art in China arouses attention, but its excessive marketization is worrisome.”

Another is the worry held by locals, represented by Wang Yishan, general manager of the Rongbaozhai Auction Company, who said, “The price of art in China has violated economic laws, and is beyond the reach of the most successful entrepreneurs. Obviously, there are bubbles in this sector.” And artists worry where the false market fever will lead the art.

“Now we have greater freedom, but at the same time there are more temptations. People have lost the capacity to focus on something. In my opinion, a great misunderstanding is that people measure freedom using the yardstick of whether people are under control. People think that the government has relaxed its restrictions, and therefore people enjoy greater artistic freedom. Actually, the market and commercial interests deprive people of the ability to think freely. In my opinion, now it is the market, not the government, which is restraining peoples freedom. Of course, on the other hand, peoples attitude towards politics is becoming more mature,” said Xu Bing, standing in front of his 1988 work, A Book from the Sky.

Chinas modernist era of artistic creation began by imitating the West. But following its development, the West has controlled the orientation of Chinese modern art. On the other hand, in the past few years the government has become more tolerant of modern art, and artists have become docilewhere once they were rebellious and possessed of an independent spirit. There are two standards measuring an outstanding artist – one is the spirit that is independent from social realities, and the other is artistic quality. According to these two standards, there are seldom any genuinely outstanding figures in Chinas modern art circles. Therefore, there should be a period of reflection.

“I think that while recalling the 1980s, artists are coming back to the starting point of Chinas contemporary art, and thinking about its future,”said Xu Bing. “We should seek the humanism we have lost, an artistic spirit that fights independently when globalization, marketization and institutionalization are dominating the world. I have a dream – that is, Chinas modern art is not merely exhibits and commodities. It should be a field like science, religion and philosophy that can produce positive changes in the culture of China and the world,” said Gao Minglu, now an art curator and teacher in the United States.

Important Dates in Chinese Contemporary Art

June 15, 1979: The magazine World Art is founded in Beijing, the first periodical in the Peoples Republic to cover contemporary Western art.

1979: A mural in the terminal building of Beijing Capital International Airport depicting images of nude women sparks an uproar throughout the country.

Sep. 27 to Oct. 7, 1979: The first non-governmental outdoor art show in the nation, the Star Art Exhibition, opens next to the National Art Museum of China.

1985: A contemporary art fad sweeps through China, known as the “85 New Tide.”

December 1986: Peking University hosts a performance art show called “Concept 21·Art Presentation.” It is the most daring avant-garde spectacle held up to that time.

February 1989: The China/Avant-Garde: No U-Turn exhibition sums up the accomplishments of Chinas contemporary art scene during the 1980s. Several hundred works by approximately 200 Chinese artists go on display, covering conceptual, performance and installation art. The event makes international headlines when two of its performance pieces, the “gunshot” and the “bomb threat,” provoke a police response and the venues temporary closure.

January 1991: Hunan Fine Art Publishing House launches the magazine Art· Market, signaling the first instance of art being addressed in market terms in the Peoples Republic. The change paves the way for contemporary Chinese art to emerge on the world scene.

January 1991: “I Dont Want to Play Cards with Cézanne and Other Works” opens at the L.A.-based Pacific Asia Museum, the first major exhibition of avant-garde Chinese art in the U.S. In addition to a show of 41 works by 20 Chinese artists, the event features a series of lectures and discussions on Chinese contemporary art.

1992: Media coverage of the Art Village at Yuanmingyuan begins appearing, paving the way for the subsequent emergence of Chinas artistic communities in the popular media.

October 1992: The Guangzhou Art Biennale, the first national art exhibition in the ‘90s, succeeds in boosting the profile of Chinas pop art. It is also the nations first art event operated on commercial principles, and brings together academic, legal, business and media circles.

1994: “Post-89, The New Art of China” opens in Hong Kong, and sets off on a world tour in subsequent years. It turns out to be among the most influential exhibitions of Chinese modern art in the ‘90s, and introduces Chinese artists to an international audience.

1997: “Another Long March: Chinese Conceptual and Installation Arts in the Nineties” is held in Breda, the Netherlands. A compilation of works by 18 Chinese artists, it features new art schools, such as cynical realism and political pop art, which have been gradually recognized by the international art market, authorities and media.

June 1999: Fifty Chinese artists show their works at the 48th Venice Biennale, Chinas largest presence in an overseas art biennale. Cai Guoqiang wins the International Golden Lion for his Venices Rent Collection Courtyard.

April 11, 2001: The Ministry of Culture issues a formal notice banning performances and displays of violent and pornographic images under the guise of art. The notice includes an appendix of articles dealing with applicable laws and regulations.

2003: The China Pavilion opens at the 50th Venice Biennale, showing Chinas newfound willingness to enter the international art arena. In another first for China, it introduces the competitive selection of organizers and proposals for major international exhibitions. The Ministry of Culture sets up a panel of senior artists and critics to invite and review designs for the pavilion. It is ultimately themed as Synthi-scapes, and Fan Dian and Wang Yong are selected as its curators.

2003: The first Beijing International Art Biennale opens, the largest art event in China since the founding of the Peoples Republic. It is also the first art biennale held in China, and the first of its kind in the world sponsored by the government and held in a capital city.

April 2006: Sothebys inaugural sale of Contemporary Art Asia in New York. Chinese painter Zhang Xiaogangs Bloodline Series: Comrade No.120 fetches an eye-popping US $979,200. In November, a new auction record for Chinese contemporary art is set by Liu Xiaodongs Three Gorges: Newly Displaced Population, when it fetched RMB 22 million at the Poly autumn auction.

2007: Exhibitions about Chinese art from the 1980s begin popping up across China, inspiring retrospectives and discussions about future trends.