Railroad to Development

ASHIS CHAKRABARTI

Devout Tibetan old granny and her granddaughter. Photo by Jogod

Bringing the railways into Tibet would hardly destroy its religion and culture, for these are not objects to be stored in museums, argues.

More to it than Oriental exotica

A spectacular achievement: but whose railway is it anyway? Right from the time China prepared to bring Tibet into its railway map, a controversy has surrounded the project. Soon after the first train rolled into Lhasa on July 1 this year, Richard Gere, Hollywood icon and one of the most famous international campaigners for a "free Tibet", lamented the event in an article in the New York Times. He called it the "railroad to perdition".

I think Gere's arguments are ridiculously flawed. I would even say that his arguments are worse than those by the opponents of the Tatas' small car project in Singur. But let me first quickly go over the background to the controversy surrounding the railway project in Tibet.

To Tibet-watchers, Gere's arguments are familiar stuff. Two booklets, published in 2002-2003, outline the arguments in great detail. One of them is from the Dharamsala-based Tibetan government-in-exile. Its title is self-explanatory: China's Railway Project: Where Will It Take Tibet.

The other publication, Crossing the Line, is from the International Campaign for Tibet. The Dharamsala booklet links the Golmud-Lhasa project to the larger Chinese ambition to extend railway networks all over western China, for which Beijing earmarked US $12.1 billion during its last five-year (2001-2006) plan. The railway projects are part of a broader "western development programme". One would think that this was a legitimate, if long-delayed, strategy to reach economic development, which was traditionally confined to China's east and north-east, to backward areas in the west. In fact, Tibet - and other western regions of China, should actually have more, and not less, of railway and other projects that should try to bring their economic development on a par with that in more prosperous regions.

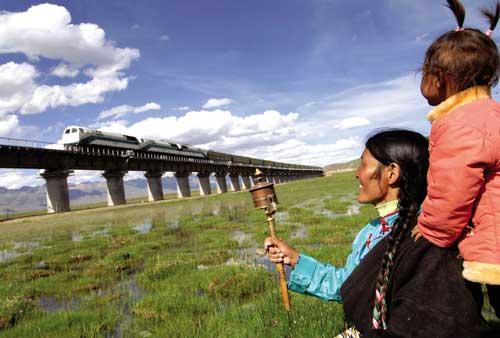

Tibetan passagers are excited when they are on a rail track. Photo by Jogod

But the anti-railway campaigners, like the anti-industry crusaders in Bengal, have other ideas. Just as the campaigners in Bengal invoke the interests of agriculture, the opponents of the railway in Tibet say that it will further destroy Tibetan "culture". There is nothing in the development projects for the "local people", say the anti-railway campaigners, just like the critics of the Singur project."The primary objectives of the extension of the railway link in western China," says the Dharamsala booklet, "are to consolidate Beijing's control in restive minority areas and to secure access to the oil-rich Central Asian republics of Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Kazakstan where the United States has already invested billions of dollars in oil exploration." It talks at length of other "casualties" of the railway project. It will lead to "extensive damage of the fragile ecosystem of the Tibetan plateau, damaging wildlife, contaminating water bodies...and inducing deflation and soil erosions as a result of escalating resource exploitation."

Both the Dharamsala document and the booklet by the ICT also make two strong points against the railway project. They fear that it will encourage a massive influx of Chinese settlers into Tibet and thereby lead to further marginalization of the Tibetans in their homeland. All this would ultimately erode the foundations of Tibetan culture and identity. They also argue that the extension of the railway to China's south-western borders with Nepal and India would upset the region's security. They doubt if the Tibetans will benefit much from the huge boost that the railway will give to tourism in Tibet.

Both the Dharamsala government and the ICT, therefore, called upon the international community to rise in protest against the project that, according to the latter, "is likely to bring more destruction than benefits to the Tibetan people".

True, you see an increasing number of Han Chinese in Tibetan towns. Much of the new commercial activities in these towns are dominated by them, while Tibetans overwhelmingly dominate agriculture and other rural livelihoods. In the towns, the Han Chinese would be doing skilled jobs in far greater numbers than the Tibetans. That is the result of Tibet's historical isolation and of its former monastic rulers' refusal to allow the common people the benefits of modern educational and other systems. Even so, few can deny that today a new generation of Tibetans work and live in situations that were unthinkable for them in centuries of feudal rule.

Animal passage way under the Qinghai-Tibet Railway in Northern Tibet. Photo by Gan Zhanglin

There have been several studies to show that the allegation of large Chinese influxes into Tibet are grossly exaggerated. The Tibetans still form 90 per cent of the population in the Tibet Autonomous Region.

Whether more Tibetan areas, which were merged with neighbouring provinces of Qinghai, Sichuan or Gansu, should have been included into the TAR is another question. What is absolutely absurd is the idea that the railway would open the floodgates of a fresh wave of Han Chinese migration to Tibet.For over twenty years, a number of highways have linked Tibet to mainland China. Northern and eastern Tibet has had the railway for many years now. If the Han Chinese were to swamp Tibet, they would not need to wait for the train. They surely could do so by taking the highways. As for the "exploitation" of the natural resources in Tibet, it is a valid charge for those who do not accept Tibet as part of China. Most governments in the world, including those of the United States of America and India, accept China's sovereignty over Tibet. Most important, even the Dalai Lama says so, even if he accuses Beijing of arbitrarily creating the TAR by leaving out other Tibetan-dominated areas and of destroying Tibetan culture through the state's interference in religious and social matters.

To a Han Chinese, the arguments of Tibet's "exploitation" would make no sense because, to him, it is as much a part of China as Liaoning, Shenzhen or Beijing. True, Tibet, like Xinjiang or Inner Mongolia, is an ethnic minority area. That is why it is an autonomous region with constitutional guarantees of privileges and special protections for the minority community. Obviously, those who object to the railway in Tibet do not accept it as part of China. Even then, how can one object to any place having its link to a railway network? Do not Tibetans need the railway as much as the people in any other part of the world?

Two Tibetan nuns are watching the passing train on Qinghai-Tibet Railway. Photo by Gan Zhanglin

The real objection to the railway or any other form modernization in Tibet actually boils down to the question of "preservation" of Tibetan culture and identity. It is an old debate whose contours are fairly well known even in other contexts. As far as Tibet is concerned, the argument still centres around the concept that Tibetan "culture" is something like a museum piece and has to be protected against all alien influences. It is not so much a love for the Tibetan people as a love affair with the world's last Shangri-la, with the last Oriental exotica. It is not so much the love of a culture as the fancy for a new cult.Francis Younghusband may have led the first Western invasion in Tibet out of imperialist motives, but every foreign mission to Tibet before and after him encountered similar cries in the name of culture. Younghusband suspected that these cries were actually a defence of a centuries-old system that exploited the people in the name of religion. He was exceptionally harsh in his condemnation of the rule of the lamas. Interestingly, communist China too is using "culture" to sell Tibet to the world. And, in Tibet, culture still means overwhelmingly religious culture. As if to expiate its sins during the Cultural Revolution, when monasteries were destroyed and monks killed, tortured and hounded, Beijing has been spending liberally over the past decade and more to restore monasteries and other Tibetan cultural institutions. Why are they doing it? How does this attempt to strengthen the Tibetan culture go with Beijing's policy of infusing the Tibetans with larger doses of nationalism? This is an aspect of today's Tibet that may be of greater significance than the impact of the railway on its economy, society and culture.

The obvious answer to the first question is that Beijing's promotion of Tibetan culture has two motives. It is aimed at luring more and more tourists to Tibet. Tourists, both from mainland China and abroad, go to Tibet mainly to savour the exotica of Tibetan Buddhism and its many spectacles. The annual income from the Potala Palace alone is over one billion Chinese yuan, although the entry is free for Tibetans. TAR officials estimate that Tibet will get an average of five million tourists every year in the next five years.

Beijing's other motive is to show to the world that the Tibetans once again enjoy religious freedom. The larger number of Tibetans going round the big monasteries prove two things - that they do enjoy this freedom more than before and that more and more Tibetans have better incomes now to be able to afford to visit these monasteries, in Lhasa or Shigatse, from their distant mountain villages. You thus have a rather unique scenario in Tibet today. On the one hand, the official policy recognizes the central role of religion in Tibetan life and promotes it. On the other hand, the government attempts all sorts of things in order to inculcate nationalistic feelings among Tibetans.As one travels through central Tibet or TAR, one, therefore, sees the five-star Chinese flag on top of most private houses, alongside the Tibetan prayer streamers. It is not difficult to understand that while the Tibetan streamer, with its five colours signifying the sky, earth, air, water and fire, is a fact of religious life, the Chinese flag is a political statement. It is the same nationalistic proclamation that one sees at the airport. It is called "Lhasa airport of China". The first billboard that attracts your eyes as you reach the airport says, "I love my country".

The author in front of the wall of the Potala Palace.Photo by Zhang Xiaoyu

For the government in Beijing, though, there is no contradiction in this. According to it, anywhere in the world, the people can have dual identities - local and national. It is particularly so for minority populations. We saw a strange manifestation of this argument at the Tashilhunpo monastery in Shigatse, which is the traditional seat of the Panchen Lama. Pictures of Mao, Deng Xiaoping and Jiang Zemin adorned a wall of the meeting hall along with those of the last two Panchen Lamas. Next to them was a picture of Hu Jintao with the current Panchen Lama. The world knows by now that the Panchen Lama, unlike the Dalai Lama, has had the approval of the Chinese authorities. But what a Chinese official said to explain the co-existence of communist leaders and Panchen Lamas in the same picture gallery was rather extraordinary. "Tibetans had always looked upon the rulers in Beijing, whether emperors or communist leaders, as reincarnations of the Buddha", he said. One's first reaction would be to laugh it away. But then, this was another example, if somewhat bizarre, of Beijing's historical claim on Tibet. Beijing knows, though, that it is far easier to lay railway lines across Tibet's mountains than to win its battle for the minds and hearts of the Tibetans. That so many Tibetans - and the Dalai Lama - continue live in exile are a constant reminder of this fact.

And, things continue to happen in Tibet to suggest that Beijing's battle is far from over. Even during our stay in Lhasa, the police fired on a group of Tibetans fleeing to Nepal across a mountain pass on their journey to Dharamsala. One woman was killed and several others injured. Even so, some 30-odd men and women managed to cross over to Nepal. There can be no doubt that the railway and other new economic projects will bring more prosperity to Tibet and Tibetans. Also, there will be Tibetans who, for all their better economic conditions, would flee China's Tibet to find their freedom in exile.