TIBET’s LAST CARAVAN CHARGED WITH TRANSPORTING SALT(VII):BARTER TRADE BETWEEN FOOD GRAINS AND SALT

GYAYANG XIRAB

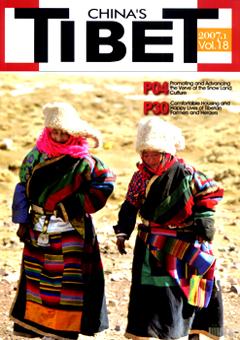

House of herders in Northern Tibet.

By setting out for saline lakes in spring, Tibetan caravans on horseback return to farmlands in autumn to barter salt for agricultural products.

Merchant caravans on horseback dress rather better than the caravans for bartering salt; they cross comparatively highly populated farmlands and pass through numerous nomadic villages. They do not want to lose face so they dress appropriately. Traditional barter trading is alive and well, with no sign that it is going to decline. Of course, some ambitious folks still enter cities to do business anonymously. That is a new phenomenon.

Barter of Agricultural Products for Nomadic Products

Nowadays, though modernization of their housing has already become a reality for herdsmen in North Tibet, this does not mean that they want to give up their nomadic way of living. Rather, they have changed their living pattern from camping where water and grass is available, to settling down seasonally at certain fixed locations. Several households live together at annual camp spots. The sites for nomadic villages need to be chosen with care. Usually, sites backed by mountains and facing grassland with reliable water resources are the ones to be considered by herdsmen.

When the weather warms up, livestock will no longer need to be fed in a pen. Herds devour all the dried grass in the autumn, and the tender shoots have yet to sprout, but herdsmen move out - at least, those with pregnant ewes must transfer to places where fresh grass is available. The season for delivering lambs is most important. The whole years... farming rests on a good start in spring and it is no exception in nomadic areas. When a short summer follows a long spring, herdsmen, one after another, move back and settle down again at the original place. They start to produce butter and milk. Dozens of thunderstorms blow autumn away and summer is just like a short dream. With the harsh and endless winter, yaks and sheep grow fat. Tibetans slaughter the yaks and sheep, while murmuring prayers, and prepare for winter. That is the nomads... most delicious food. All preserved meat could last until next year when livestock could produce milk again. In one book, it is written as follows.

Reviewing the living style and production methods, products like meat, butter, various milk products and salt, are not enough to meet Tibetans' requirements. Though herdsmen can produce meat, milk and salt, apart from those, they still need barley, tea and other necessities. It is unnecessary to repeat that salt is such a significant item for nomads, who are predominately living off meat. However, barley is also indispensable for their daily lives. The quantity of livestock products varies considerably according to season. When summer and autumn come, nomads are not used to slaughtering their animals even though the quantities of produced milk, butter and yogurt are greatest during this period. They therefore demand a rather big amount of barley so that they could have food to replace dairy products in these off-seasons. When summer replaces spring, meat and food, preserved for the whole winter, are almost exhausted. At this period, animals are not fat enough, and the quantity of milk products is low. Without sufficient barley, nomads struggle to maintain their lives. They need barley and tea, but there are no such products unless they could trade from somewhere. Therefore, barter trade emerges amongst nomads.

Thereby, farmers and merchants (including official and private merchants and monks who embark on business from monasteries) become trade partners. Nomads provide salt and dairy products, and farmers in return offer barley. Such trade activities are called as "Salt and food grains barter". Herdsmen sold animal products to merchants, including substantial quantities of sheep wool, and merchants supply herdsmen with tea and other products. Here it is referred to as "tea and wool barter".

Trinla,the young daughter of Kelsang Wangdu

The major components of trade in the north of Tibet are "salt and food grains barter" and "wool and tea barter". (See "Herdsmen in North Tibet - Social and Historical Studies in Nagchu Prefecture of Tibet", written and edited by Gelek, Liu Yiming, Zhang Jianshi and An Caidan).

Trade activities between farmers and herdsmen in Tibet usually happen in autumn. During this period, all kinds of products are in the process of production or may have already been accomplished; salt is already preserved for several months and waits for exchanging for barley in order to have enough food grains for next year. Actually, it is just at the time when farmers have already harvested and they are ready and pleased to offer exchange for salt, meat products, dairy products, leather and wool. However, the quantity of wool collected by farmers is very limited. Cash income for purchasing other industrial products by nomads mostly derives from selling sheep wool and goat wool. Due to intervention from government and also to the changing ideology of herdsmen, at present, more and more living domestic animals are sent to slaughtering markets or handed over to slaughtering merchants. This is actually another source for herdsmen to get cash. Nevertheless, herdsmen prefer to sell their livestock at a lower price to local officials or government servants rather than slaughtering merchants. They believe that it is immoral to sell yaks and sheep, which they have raised for years, to those merchants.

Government agencies and monasteries merchants always purchase wool. Historically, the Gaxia Government and monasteries intervened and controlled free and direct trade between herdsmen and private business. They were accustomed to collect wool through tax and/or buy at a very low price. Only after paying their heavy wool tax at the end of the year, could herdsmen relax. Otherwise, they would suffer punishment if they could not meet their tax obligations.

Cooking at camp.Photo by Jogod

After peaceful liberation and under the policy of planned economy, wool was sold directly to commercial companies of townships and counties. Herdsmen got cash directly. Since the introduction of a market-orientated economy, herdsmen have had more flexibility to trade with state enterprises. They not only received cash from those companies, but also alternatively bartered for barley, flour, rice and rape oil. Such exchange greatly assisted those herdsmen who have no access to long distance transport. In the 1990s, influenced by the world market, wool prices dropped once more, and the state enterprises could not provide more benefits. With further opening up in China, the market situation, by which the government purchased wool through state enterprises, was broken up, allowing free trade of wool.

According to regulations, every household should submit a certain quantity of wool to state centerpieces, and herdsmen could freely utilize the rest. After fulfilling his quota of wool to state enterprises, Kelsang Wangdu still had abundant wool, including those produced by his home livestock and the ones collected from other local herdsmen. He often barters for sheep wool, goat wool, and animal hides from local herdsmen or buys from them at a slightly higher price than the state enterprises offer, and then he sold out to private merchants.

While the documentary filming was in progress, Mr. Tan, the head of a film production team, was still not satisfied. He decided to add something to the documentary: "Why don't ask Kelsang Wangdu to barter in Lhasa", he asked me.

"It is unlikely. Kelsang Wangdu prefers to go to Nagqu, the biggest distribution centre in Tibet. Anyway, I will discuss it with him", I said. This was just my modesty because I understood perfectly that Kelsang Wangdu very much wanted to sell his goods. I went to him and passed on the message. He was so happy and immediately came up with requests that, if the team offered him assistance to freight goods out and in, he was willing to go to Lhasa. Actually, that was exactly what I had anticipated. Thereafter, I tried to make it become possible. Nevertheless, Kelsang Wangdu requested more than expected. He planed to sell the hides firstly at Nagqu, and then travel to Lhasa for wool. Obviously, his intention was to get the highest profits from his trading. But unfortunately, Mr. Tan refused his proposal and asked him to go to Lhasa directly.

Kelsang Wangdu made preparations before he set out. He claimed that he knew perfectly how to make a deal with those ethnic Hui. He soaked his hides in the river first, piled them up, and then mopped up the blood. Notwithstanding, he still could not outsmart those elders of ethnic Hui.

In fact, Kelsang Wangdu also had another motive to visit Lhasa. That was to go for a pilgrimage there. As father of his daughter, this was a way he could show his affection before she married. If she married in the future, it might be inconvenient to bring her with him. Moreover, blessings brought by pilgrimage would come to the individual, but marriage celebration is a gift for others. This was the fundamental conception of economic value and belief of Kelsang Wangdu.

Trade Caravan of Herdsmen

Kelsang Wangdu was good at getting along with private merchants, but on contrary, Wangchen, his son, had limited capacity and was hard to compare with Kelsang Wangdu. Therefore, two of them took on different responsibilities based on their talents. For years, herdsmen had gotten along with rather conservative individuals while they were bartering. For instance, in Village Five, herdsmen, like Wangchen, Buchung, Dondrup, and Tanor, preferred to extend their business at Lhunmo County of Lhasa Municipality; but Dongya, Sokya, and Samdo would like to go to Tobgyai and Tsar Township in Namling County of Shigatse Prefecture to do their business.