返璞归真:瓦格纳主义前的瓦格纳

应该说我也算得上有些年纪了,所以我还记得多年前指挥家罗杰·诺林顿(Roger Norrington)提出了一个在当年算得上激进的概念:他参考了考古研究以还原古乐器,并按时间顺序演奏贝多芬的全套交响曲。在那之前,所谓“历史真实性”仅研究到贝多芬之前——从字面上看,音乐学的时间线只延续到莫扎特——而到现场观赏贝多芬交响曲音乐会的观众明显分为两派:古乐器可以让我们重新认识到巴洛克曲目所蕴含的神韵,但套用到古典时期最著名的交响乐曲上的话,可以达到同样的效果吗?大众众说纷纭。

我的答案是热烈肯定——“可以”,但最终还回归到“不可以”。从好的方面来说,我们聆听的演出没有添加后浪漫时期附在贝多芬头上的那些响亮的、强调他“举足轻重”地位的包袱。如果我们按时间顺序聆听全套交响乐的系列演出,可以察觉到作曲家日趋成熟和历经磨炼的过程,更容易了解贝多芬的“三个创作时期”——从一开始极具潜力地师从海顿(虽然有点不羁),到最终他完全失聪,可他的内耳又明显专注于超越他的、未来的声音世界。

然而那时的我年少轻狂,心里不由会质疑权威。诺林顿的演绎在我当时还未积累丰富经验的耳朵听来,好像欠缺了些什么。我听到的不仅仅是作曲家的成长与变化,当年的乐器也经历了飞速的发展。对于一个以“时代乐器运动”为名的系列音乐会来说,在演出贝多芬的《第一交响曲》和《第九交响曲》时用上同样的乐器,显然是一个错误的抉择。

幸好,无论是演奏家还是观众都很快就适应了。古典音乐主流开始变得如此善于复古演奏手法与风格,有时候区分主流演奏会与复古演出的唯一标准是:乐手们拿着的是现代乐器还是古乐器。而关于“历史真实性”这个议题,通常不以幽默著称——尤其是在利用已经过时的技术演绎当代“新”音乐上,甚至带有一层讽刺意味。约翰·凯奇(John Cage)创作于1954年的《虚构的风景第四号》(Imaginary Landscapes No. 4)中,运用了十几台收音机同时随机播放不同的音乐节目;但最近它的演出却出现困难,因为如今大部分的电台直播都在做“脱口秀”而很少播放音乐,于是主办方在演出编排方面必须重新调整。

因此,去年当我听说以历史真实手法演绎巴赫而著称的德累斯顿音乐节,声称要把“历史真实性”的焦点放在另一位长居莱比锡的作曲家——理查德·瓦格纳身上时,我有点吃惊。2023年,德累斯顿音乐节开启了历时四年的《指环》系列,揭幕演出用上了瓦格纳当年的古乐器,也考证了当年的声乐唱法以及咬字发音等。他们请来指挥长野健(Kent Nagano),与布拉格国家歌剧院与科隆协奏团合作,还为公众设立了讲座与工作坊,以便于大家更深入地认识瓦格纳的年代。

我错过了2023年演出的《czXdLsDtr4kwiKB42d1wVEbJRhUeGWq4Ku1bznQmquU=莱茵的黄金》(Das Rheingold)与今年5月的《女武神》(Die Walküre),但德累斯顿还有两部《指环》剧目将呈现在舞台上——而且,因为有不少合作伙伴参与其中,这个制作的演出机会应该还会持续一段时间。但我却禁不住猜想,那些“死忠派”瓦格纳粉丝与交响乐界的贝多芬迷相比,将会有何种反应。

传统与真实历史之间的差异往往很大,尤其是当你面对着那些历史潮流的引领者。就算是具有前瞻性的艺术家,都不可能是凭空出现的。这些艺术家在青年时代往往受到各种因素的影响,后来它们却被加工美化了——如果不是引领者本人的行为,就是后来拥护他的追随者们为之。

我在中国最难忘的歌剧之夜是在2012年,国家大剧院搬演瓦格纳《漂泊的荷兰人》。大多数人被强卡洛·德·莫纳科(Giancarlo Del Monaco)所设计的两艘实物大小的船只在舞台上相遇打动(差不多等同于将电影《加勒比海盗》的开头片段延伸了30分钟),但对我来说,最深刻的印象来自乐池。

某些所谓“资深”人士批评了吕嘉处理音乐的手法。吕大师多年来领导维罗纳的歌剧演出,指挥演出的乐句起伏,会有意识地带有意大利风格,与德国风格截然不同。很多人却埋怨是吕嘉分不清德意之别。

可是,重点就在这里:事实上年轻的瓦格纳钟爱美声唱法,尤其是贝利尼的歌剧。我们现在所谓的“瓦格纳式”唱法其实源自他后期创作的歌剧——特别是《指环》系列,而这种唱法又被追溯套用到他早期的歌剧作品中。在国家大剧院版的《漂泊的荷兰人》里——那是瓦格纳毕生首次获得成功的作品——吕嘉确实故意忽略了传统,相反,他考虑到历史。

虽然我与德累斯顿的《女武神》失之交臂,但一个月之后在香港还是过足了瓦格纳瘾,观看到一场与众不同的《漂泊的荷兰人》的瓦格纳演绎。本地人都取笑地说,即将卸任的音乐总监梵志登在演出后的几天内就要坐飞机“漂泊”回国,但是这版《荷兰人》的确为这位荷兰指挥家在香港的12年任期画上了圆满的句号,也让他为香港管弦乐团(简称“港乐”)带来荣耀的功绩:为拿索斯(Naxos)灌录的全套《指环》后,《留声机》(Gramophone)杂志2019年将港乐评为“年度最佳管弦乐团”。

港乐的《荷兰人》也录了音,同样将由拿索斯发行。从一开始的号角到绚烂的弦乐声部,都让人联想起几年前那次历时四年的《指环》旅程。声量强弱的大对比没有减少任何音乐的强度,演唱阵容也全都是富有经验的瓦格纳歌手,他们的功底同样扎实(甚至因为演员数量较少,发挥要比《指环》更一致稳定)。

演出唯一令人遗憾的,就是缺乏意大利美声风格唱法。梵志登的《荷兰人》没有忠于瓦格纳创作这部作品的年代。他的演绎更像一位成熟的作曲家回眸一望,凸显了一些未来的种子,而忽略了音乐中所拥有的年轻情怀。因此,这部《荷兰人》只能算是半个瓦格纳的图像。可是,对于指挥与乐团而言,目光由大获成功的《指环》回望,用同样的方式重塑过往的音乐,可能是他们能想到的唯一的方法。

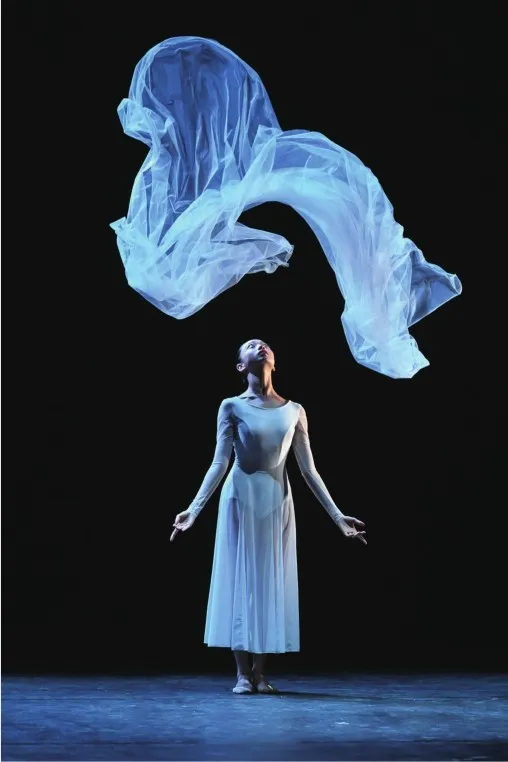

在这里我给这次瓦格纳的话题加上一个尾声:我刚于8月中旬在香港看了普契尼的首部舞台作品《群妖围舞》(Le Villi)。一直以来,我对《群妖围舞》都有点偏爱,部分原因是它证明了成功人士的第一次出击通常都不太成功。《群妖围舞》的音乐与舞蹈的比例看起来有一点尴尬,整个故事的架构也略显笨拙,乐队配器听起来过于沉重而令人感觉不舒服。尽管该作品有这样那样的缺点,你还是从中听得出青年普契尼在探索他成长以后可以达到的高峰。

上文提到,瓦格纳深受老一辈的意大利歌剧作曲家的影响,而青年普契尼则深受瓦格纳的影响。有几位同行曾经讨论过,普契尼才是实现了瓦格纳理想中“整体艺术”的人,甚至比那位德国前辈更为成功(尽管我认为,他们的论点是基于对令人难忘的旋律的偏好,还有,歌剧时长适中而不是演到午夜后才散场)。

这场《群妖围舞》让我首次认识香港一个非营利机构,名为“众乐乐”(Tutti),演出集合了香港飞跃舞蹈学院与非凡美乐(另一家主要的香港歌剧制作机构),还有香港芭蕾舞团与深圳歌剧舞剧院的艺术家。在乐池带领19人乐队的是杜洛沙(Isaac Droscha),他在舞台上饰演的歌剧男中音的角色,广为人知。

我曾经观赏过制作更为精良的《群妖围舞》——包括在上海歌剧院——但是,香港的这场演出的确捕捉到青年普契尼的精髓。换句话来说,制作的活力与魅力并重,超出了实际上的舞台技术。在杜洛沙的最佳状态下,带领着乐手们与歌唱家完美契合,他们一同呼吸、一同塑造乐句——这对乐手们来说是最难以捉摸的技巧。

可惜,这场演出无法企及的,就是与瓦格纳建立任何的关联。乐池里只有19人——我猜大概是我的要求太多吧。

I’m old enough to remember when the conductor Roger Norrington came up with a then-radical notion to conduct all the Beethoven symphonies in order on period instruments. Up till then, “historical authenticity” had only gone so far—literally, up to Mozart on the musicological timeline—and audienc- es came into the Beethoven project clearly divided over whether or not the same sense of discovery that period instruments brought to the Baroque repertory would have a similar effect on the most famous symphonies in the classical cannon.

The answer was an enthusiastic yes—but ultimately, no. On the plus side, the audience got to hear the music of Beethoven without the stentorian“importance” and late-Romantic gloss added by later generations. And like nearly all symphonic cycles, listeners could discern the composer’s growing maturity, moving through his famous “three periods”from the promising (if unruly) student of Haydn to the deaf master whose inner ear was clearly focused beyond the sound world of his time.

Back then, though, I was also young enough to question authority, and even to my developing ears something crucial was missing. It wasn’t just the composer who was changing; the instruments of the time were also transforming at a rapid pace. For a gather-ing that called itself “the period-instrument movement,” using the same instruments for Beethoven’s Symphonies Nos. 1 and 9 seemed a significant error.

Fortunately, both musicians and audiences caught up quickly. The classical mainstream became so adept in adapting period performance practices that sometimes the only way to tell a standard orchestral performance from a historical recreation was the use of modern instruments. Period authenticity—not generally known for its humor—even took on a layer of irony, especially in performances of “new”music using outdated technology. (A few years ago, John Cage’s 1954 piece Imaginary Landscapes No. 4, with a dozen radios randomly juxtaposing different musical broadcasts, had to be retooled when the majority of stations only offered talk radio.)

So I was a taken aback a bit last year when I heard that the Dresden Music Festival would be taking the historic approach that worked so well with Bach and training it on another longtime Leipzig resident: Richard Wagner. In 2023, the festival opened its fouryear recreation of the Ring Cycle focusing not just on Wagner’s original instruments but also the vocal and linguistic practices of the period. Conducted by Kent Nagano, the project joined together forces from the Prague State Opera and Concerto K?ln, offering lectures and public workshops to introduce audiences to Wagner’s time.

***

I missed both Das Rheingold in 2023 and Die Walküre this year, but there are still two Ring operas—and with so many collaborators, the project should be around for some time. I did wonder, though, how the reactions of die-hard Wagnerians would compare to the Beethoven worshippers in the symphonic world.

Gaps between tradition and actual history are often quite broad, particularly when you’re dealing with history’s trendsetters. Not even visionaries emerge from a vacuum, and it’s often the influences of youth that get airbrushed from the picture—if not by the visionary in question, then by future generations of followers.

One of my most memorable operatic nights in Chi- na was the premiere of Wagner’s Flying Dutchman in 2012 at the National Centre for the Performing Arts. Most people were struck by director Giancarlo Del Monaco’s vision of two life-sized ships meeting on stage (essentially extending the opening of Pirates of the Caribbean for a good half hour), but for me, the most memorable part of the evening came from the orchestra pit.

Quite a few “knowledgeable” people criticized LüJia’s approach. As a longtime veteran of Verona, Lü led his forces with a clear sense of Italian phrasing, quite distinct from Germanic styles. Many people grumbled that Lü couldn’t even tell the difference.

But here’s the thing: the young Wagner was very smitten by bel canto, particularly the operas of Bellini. What we call “Wagnerian” singing developed after Wagner wrote his later operas—most notably his Ring Cycle—and retroactively applied to Wagner’s earlier operas. In the NCPA’s performance of Dutchman—Wagner’s first major success—Lü was indeed ignoring tradition; instead, he was paying attention to history.

I missed Walküre in Dresden, but got a different Wagnerian fix the next month with a very different look at The Flying Dutchman in Hong Kong. Ignoring the local joke that outgoing music director Jaap van Zwenden would be on a plane back to Amsterdam a few days after the final curtain, Dutchman did crown the Dutch conductor’s 12 years at the helm by honoring his greatest achievement: a Ring Cycle, recorded for Naxos, that led Gramophone magazine to name the Hong Kong Philharmonic “Orchestra of the Year” in 2019.

The Philharmonic’s Dutchman, also recorded for Naxos, recalled the successes of the previous four-year journey, from the score’s opening horn calls to general string-section bombast. Stark dynamic contrasts lost none of the music’s intensity, and the cast of veteran Wagnerians was similarly solid (and, if anything, more consistent, since it had fewer singers).

The evening’s one downside, however, was a notable dearth of bel canto. Van Zweden’s Dutchman, rather than being true to Wagner’s time, offered a glimpse of the mature composer looking backward, highlighting kernels of future truth while ignoring the music’s youthful present. As a portrait of Wagner, it was only half the story, but for a conductor and orchestra looking backward from the vantage of the Ring, it was probably the only way they could think to tell it.

***

To add an Italian coda to all this Wagner talk, I also saw a mid-August performance in Hong Kong of Le villi, Puccini’s first stage effort. I’ve always been partial to Le villi, partly because, like most first attempts by successful people, it proves they weren’t always successful. In Le villi, music and dance struggle awkwardly for supremacy, the structure is a bit clumsy and the orchestrations too heavy for comfort, but through the flaws you can still hear the young Puccini actually figuring out what he wants to do when he grows up.

Much as Wagner was heavily influenced by earlier Italians, the young Puccini was heavily influenced by, well, Wagner. Several of my colleagues have argued that Puccini actually fulfilled Wagner’s ideal of Gesamtkunstwerk (or “complete work of art”) better than Wagner did (though I think their reasoning is often guided by a yearn for memorable melodies and a desire for operas to end on the same calendar day they begin).

Le villi was my introduction to Tutti, an organization joining forces with Hong Kong’s Supreme Dance Academy and Musica Viva (another local opera presenter), as well as tapping artists from the Hong Kong Ballet and the Shenzhen Opera and Dance Theatre. A 19-piece pit ensemble was led Isaac Droscha, better known for appearing on stage in operatic baritone roles.

I’ve seen more polished productions of Le villi—including one at the Shanghai Opera House in 2009—but this one did actually capture the essence of a young Puccini, which is to say it offered more energy and charm than actual stagecraft. At his best, Droscha imparted to his musicians the one thing that usually proves most elusive to instrumentalists: the ability to breathe and phrase with the singers.

What the performance did not have, alas, was much connection to Wagner. With only 19 players in the pit, that was probably too much to ask.