Childhood sleep: physical,cognitive,and behavioral consequences and implications

Jianghong Liu ·Xiaopeng Ji·Susannah Pitt·Guanghai Wang·Elizabeth Rovit·Terri Lipman·Fan Jiang

Abstract Background Sleep problems in children have been increasingly recognized as a major public health issue.Previous research has extensively studied and presented many risk factors and potential mechanisms for children’s sleep problems.In this paper,we aimed to identify and summarize the consequences and implications of child sleep problems.Data sources A comprehensive search for relevant English language full-text,peer-reviewed publications was performed focusing on pediatric sleep studies from prenatal to childhood and adolescence in a variety of indexes in PubMed,SCOPUS,and Psych Info published in the past two decades.Both relevant data-based articles and systematic reviews are included.Results Many adverse consequences are associated with child sleep def iciency and other sleep problems,including physical outcomes (e.g.,obesity),neurocognitive outcomes (e.g.,memory and attention,intelligence,academic performance),and emotional and behavioral outcomes (e.g.,internalizing/externalizing behaviors,behavioral disorders).Current prevention and intervention approaches to address childhood sleep problems include nutrition,exercise,cognitive—behavioral therapy for insomnia,aromatherapy,acupressure,and mindfulness.These interventions may be particularly important in the context of coronavirus disease 2019.Specif ic research and policy strategies can target the risk factors of child sleep as well as the efficacy and accessibility of treatments.Conclusions Given the increasing prevalence of child sleep problems,which have been shown to affect children’s physical and neurobehavioral wellbeing,understanding the multi-aspect consequences and intervention programs for childhood sleep is important to inform future research direction as well as a public health practice for sleep screening and intervention,thus improving sleep-related child development and health.

Keywords Behavior·Child sleep·Consequences·Implications·Neurocognitive·Physical·Prevention/intervention

Introduction

Unhealthy sleep in children and adolescents has been continually recognized as a major health issue and has received great attention in recent years by researchers,healthcare providers,families,caregivers,and school nurses/counselors [1— 3].It is estimated that approximately 20%—40% of infants and school-age children have poor sleep health,such as waking overnight,difficulty falling asleep,and difficulty sleeping alone [2,4].Also,up to 75% of high school students sleep less than recommended eight hours per night and report impaired sleep quality[5,6].Healthy sleep and circadian rhythm are critical to the physical,cognitive,and psychosocial development in children and adolescents [7— 10].For example,insufficient nighttime sleep and daytime sleepiness are associated with poor academic performance [11].Persistent sleep problems in children predict clinical psychosocial symptoms during adolescence,such as aggression,attention def icits,social anxiety,and depression [12 ].Additionally,insuffi-cient sleep and poor sleep quality have been linked to cardiometabolic risk factors (i.e.,obesity) [7],which increase the risk for cardiometabolic morbidity and mortality later in life [13— 15].Therefore,elucidating the health consequences of unhealthy sleep and identifying evidence-based sleep interventions will contribute to promoting health and well-being in children and adolescents.

In the current review,we aim to identify the physical,cognitive,and behavioral consequences of poor sleep;outline prevention and intervention strategies;and discuss recommendations for future research and practical applications.We reviewed data-based articles and systematic reviews on pediatric sleep health (2002—2022) for this study (detailed search strategies and inclusion/exclusion criteria were provided in the Supplementary Methods).

Consequences of sleep problems

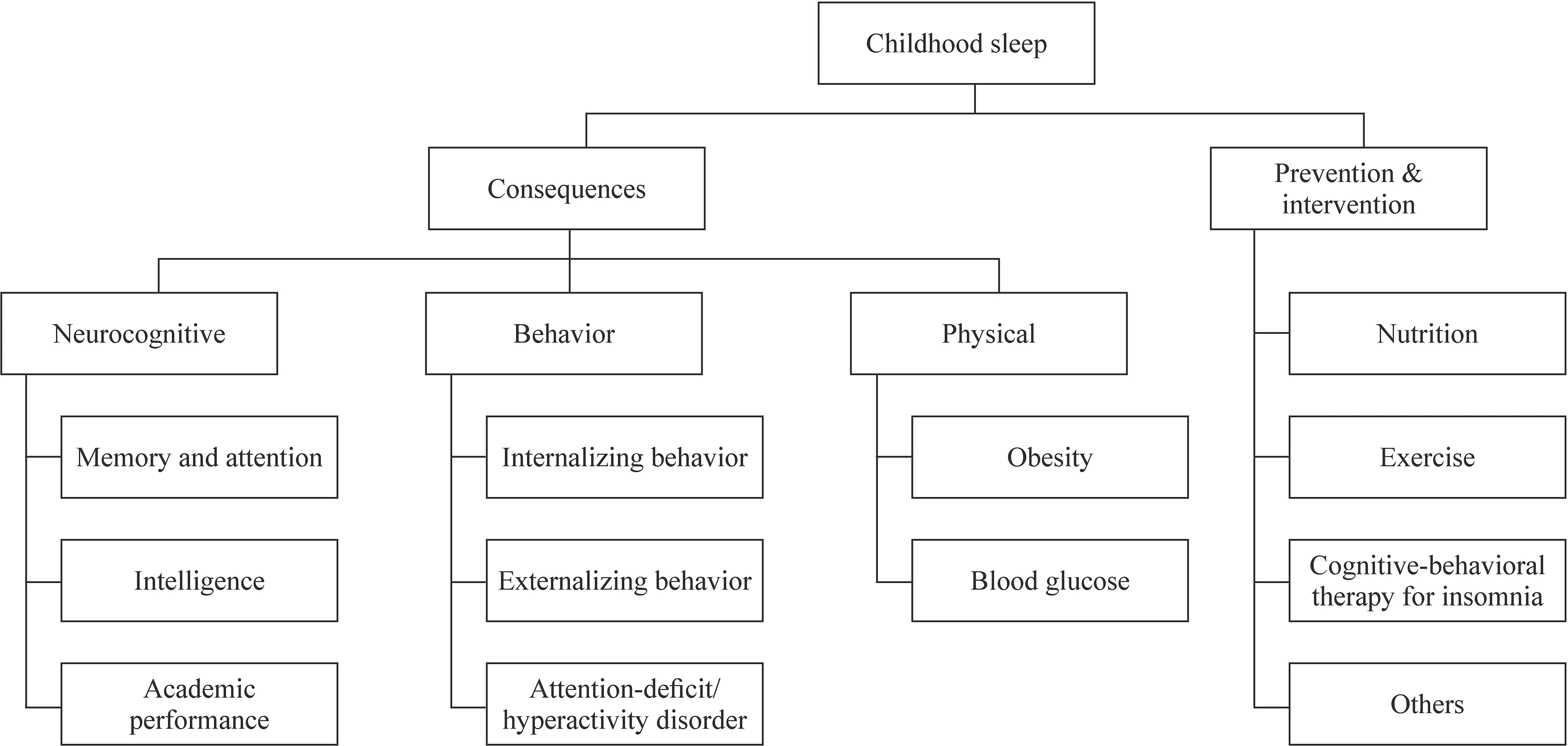

It is important to recognize the consequences of unhealthy sleep throughout childhood and adolescence,particularly during sensitive periods of development (e.g.,at 5—6 years when starting school;when going through puberty) [16— 18].The following section details specif ic common consequences faced by children and adolescents experiencing poor sleep health,which are also outlined in Fig.1.

Fig.1 Childhood sleep and consequences and implications

Physical health outcomes

Unhealthy sleep in children has been linked to many negative health outcomes.Here,we are particularly highlighting its potential role in cardiometabolic factors.Cardiometabolic risk factors (e.g.,obesity,high blood pressure,impaired fasting glucose,high triglyceride and low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels) develop in childhood and adolescence [13— 15].About 10%—30% of children and adolescents worldwide are overweight or obese [19] and 6%—39% possess multiple cardiometabolic risk factors (e.g.,metabolic syndrome) [13— 15].Cardiometabolic risk factors in early life predict cardiovascular disease,type 2 diabetes mellitus,and subsequent mortality in adulthood [13— 15].Unhealthy sleep indicators,such as short or very long sleep,fragmented sleep,insomnia symptoms and daytime sleepiness,are robust predictors of obesity,impaired glucose metabolism and high blood pressure among children and adolescents[7].Unhealthy sleep may alter levels of appetite-regulating hormones (i.e.,leptin,ghrelin),glucose metabolism and inf lammatory biomarkers,thereby affecting cardiometabolic factors [20].However,f indings on the association between sleep duration and blood lipids are inconsistent [21].The following section provides a literature review of the most common cardiometabolic risk factors (obesity and impaired glucose metabolism) among children and adolescents.

Obesity

Childhood and adolescent obesity has increased signif icantly in the past few decades and is now considered a major public health concern [22].Many factors contribute to the rise of obesity,including screen media overuse [23],lack of exercise [23],and obesogenic diet [24].However,more attention recently has been given to sleep as a risk factor[25,26].Prior research has consistently shown that shorter sleep duration is correlated with childhood obesity [25,27— 32],particularly among preschool-aged children [30,32]and adolescents [28,33].A longitudinal study found that shorter sleep increased the risk of central obesity for girls[26].Furthermore,both insufficient and excessive sleep were linked to short-term and long-term hyperglycemia in obese adolescents [34].More current research reports that daytime sleepiness [35],midday napping [33],poor sleep quality [36],weekday—weekend sleep variability [37],greater sleep disturbances (e.g.,night awakenings or overall disturbance score) [38],and a delayed sleep phase pattern [29]are also associated with obesity.However,the directionality of the relationship between sleep and obesity is unclear,as literature also reports that obese children are more likely to sleep for shorter durations and have more length variability between the weekdays and weekends compared with children classif ied as overweight,normal,or underweight [37].Body processes that occur during sleep greatly impact the growth and wellbeing of children and adolescents through the regulation of hormone secretions [39,40].The potential mechanism for short sleep duration resulting in obesity could be that changes in hormone levels of leptin,ghrelin,insulin,cortisol,and growth hormone inf luence weight and nutrition [25,39,41].Future research should focus on the connection between obesity and sleep duration,as well as the directionality of the relationship.Longitudinal studies may offer repeated measures of sleep assessments,in which potential confounding variables should be controlled such as physical activity,eating behaviors,and screen time.Impaired glucose metabolism

Adolescents exhibit pubertal-related decreases in insulin sensitivity [42,43] and changes in intrinsic sleep regulation,putting them at high risk for sleep-related impairment in glucose metabolism [43— 45].Despite mixed f indings [46],a growing number of studies have shown that insufficient sleep and lower sleep efficiency are associated with lower insulin sensitivity [47],greater homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance [48] and higher fasting glucose levels among adolescents with and without obesity [49].In a sleep restriction study (6.5 hours/day),a split sleep schedule (5-hour nighttime sleep with a 1.5-hour afternoon nap) had a greater impact on blood glucose than continuous nighttime sleep.Indeed,the role of naps in glucose metabolism is controversial.Evidence suggests habitual midday naps (≥ 3 days/week) are associated with an increased risk of impaired glucose metabolism indicated by high fasting blood glucose,especially among adolescents who self-reported at least 9 hours of nighttime sleep.These f indings highlight the importance of a moderate amount of sleep within a 24-hour period.

Neurocognitive outcomes

Cognitive development is one of the most important areas of development throughout childhood.Historically,research has largely focused on nutrition [50],environmental stimulation [51],and parenting [52] in relation to cognitive development.Over the past few decades,emerging research from both experimental and longitudinal observational studies also demonstrate its relationship with sleep [53,54].Insufficient sleep and impaired sleep quality have been shown to affect neurocognitive functions among children and adolescents,including attention,intelligence,and academic performance [9— 11,55].For example,frequent nighttime awakenings are associated with poor cognitive functioning in toddlers [8].Infants with nighttime awakenings for 2 times/night were found to have signif icantly higher mental development index score,as compared to those with more frequent nighttime awakenings [8].We provide a literature review on primary neurocognitive outcomes below.

Memory and attention

Due to the importance of sleep in memory consolidation[33,56],the occurrence of sleep problems has been shown to impair both memory retention and attentive behavior.Among school-aged children,those who frequently nap have faster reaction times on spatial memory functioning tasks than those who do not [33].Additionally,those experiencing high-quality sleep of sufficient duration show better memory consolidation and recall of verbal and novel words [56].Short sleep duration can adversely affect memory,including measurable impairments of short-term and working memory[9,10].

Attention is also associated with sleep quality and duration in children and adolescents.In infants,lower sleep quality predicts compromised attention regulation [57].Similarly,attention problems,such as hyperactive and inattentive behavior,in children [58] and adolescents [59] are associated with short sleep duration as a result of snoring and difficulty initiating and maintaining sleep.In regard to sleep duration,children who sleep for fewer hours during the night show measurable impairments in attention and greater levels of attention def icit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)-like symptoms [60],such as greater levels of inattention [10]and distraction [61].These associations are similarly seen in adolescents,particularly in classroom environments.Adolescents with shorter nighttime sleep durations demonstrate more inattentive and oppositional behaviors the following day [62] as well as diminished learning and unmindful manners in the classroom [53].

Intelligence

Longer sleep duration is associated with higher neurocognitive functioning,better overall IQ scores,and improved performance in perceptual reasoning and intellectual competence [63,64].Conversely,impaired performance on cognitive tasks is seen in both healthy and ADHD-diagnosed children with shortened sleep duration [65].Sleep-disordered breathing (SDB),daytime sleepiness,and general sleep problems are also associated with decreased intelligence[66,67].Children with greater sleep problems and fatigue score lower on measures of verbal intelligence quotient,performance intelligence quotient,and full-scale intelligence quotient [55].

Academic performance

Consequences of disturbances to sleep can be ref lected in the scholastic achievements of children and adolescents.In particular,daytime sleepiness has been demonstrated to signif icantly decrease academic achievement among studies in Finland [68],the Netherlands [69],China [11],and South Korea [70].Less nighttime sleep can impair academic success,whereas longer sleep duration is positively associated with overall better academic performance [11,63].Furthermore,children with sleep problems during the night due to SDB and snoring show poor academic performance [71] and perform worse on measures of executive and academic functioning [66],mathematics,and spelling [58].Specif ically,among adolescents,those suffering from poor sleep quality are more likely to have both lower self-reported end-ofterm grades and parent-reported academic performance [69,72].In China,during periods of high academic demand and stress,the vast majority (94.4%) of high school adolescents had a sleep duration of less than eight hours,and prolonged sleep latency was associated with poorer self-reported academic performance [73].In actuality,sacrif icing sleep to study longer does not lead to a better academic score [74].

Emotional and behavioral outcomes

Children and adolescents’ mental health well-being has been increasingly recognized as public health concerns,which contribute to child development and milestone achievement.The prevalence of behavioral and conduct disorders in children and adolescents has risen in recent years.These

disorders include ADHD,anxiety,depression,oppositional def iant disorder (ODD) and conduct disorder.From the 2016 National Survey of Children's Health with a representative sample,it is estimated that about 7.4% of children have behavioral and/or conduct disorders,7.1% have anxiety,and 3.2% experience depression in the United States [75].ADHD may be prevalent in up to 9.8% of 3-to 17-yearold children in the United States [76].While many factors have been contributed to these mental health problems,both laboratory and epidemiological studies have demonstrated the role of sleep in the development of the brain [8,77,78],which further impacts emotion and behavior [78].Studies have shown that longer nighttime sleep duration and fewer sleep disturbances are associated with a more mature empathy pattern in young preschoolers [79].The associations are more prominent in children at the higher end of the empathy spectrum and vary by sex [79].Conversely,sleep problems can be both a predictor and outcome of negative behavior problems including internalizing behaviors (directed towards oneself) and externalizing behaviors (directed towards others) in children [80,81].For example,disruptive sleep in children and adolescents have been linked to depression,anxiety,aggression,and ADHD [80,81].We provide a detailed review in the following sections.

Internalizing behaviors

The most commonly observed internalizing behaviors among children and adolescents are depression and anxiety[80].Studies show that shortened sleep durations are highly correlated to internalizing behaviors,as measured by parental and teacher reports as well as behavioral tasks [82,83].Specif ically,depression is known to be associated with sleep def iciency [84,85] and poor sleep quality [72].Anxiety,a comorbid condition with depression,also increases with decreased sleep duration [86,87].School-aged children who experience persistent sleep problems have an increased risk of anxious and depressed mood [12].Additionally,excessive daytime sleepiness is strongly associated with parental reports of anxiety and depression [35].Furthermore,sleep problems in adolescents predict an increased prevalence of anxiety and depression symptoms over time [59] as well as predict diagnoses of generalized anxiety disorder [88].

Externalizing behaviors

Disruptions to normal sleep patterns may also increase externalizing behaviors.Shorter sleep is associated with more observed and parental-reported behavioral problems and more rule-breaking [60,89],and predicts the occurrence of high externalizing behavior [82].Among adolescents,those with variable sleep patterns (e.g.,duration,timing) between the weekdays and weekends demonstrate higher levels of self-and parent-reported aggression [59,90].Furthermore,general difficulties with sleep and the occurrence of sleep problems may affect daytime behavior in children and adolescents [81].In preschool-aged children,parental report of sleep difficulties is associated with teacher-reported externalized behaviors [83].Additionally,children experiencing persistent sleep difficulties have an increased risk of aggression [12].A longitudinal study of African American adolescents demonstrated that sleep disturbances were associated with adolescent aggression,such as carrying,handling,and utilizing a knife and/or gun and quick temperedness [91].To note,sleep problems in preschoolers are associated with externalizing behaviors in adolescents [92].

ADHD and other behavioral disorders

Unhealthy sleep in children and adolescents may exacerbate the symptoms of behavioral disorders such as ADHD[93— 95].Both short [93] and long sleep duration [94],actigraphy-assessed sleep fragmentation (i.e.,frequent and long wake after sleep onset) [95],more frequent daytime napping,insomnia,sleep terrors,sleep-talking,snoring,and bruxism[94] are associated with ADHD.Using self-reports and parental reports,a cross-sectional study found that ADHDrelated behavioral problems were associated with difficulty falling and staying asleep in adolescents [96].Children with shorter sleep duration are at increased risk of inattention,impulsivity,and hyperactivity [61,97,98] and higher scores on a parent-reported ADHD measure [97].Shorter sleep duration and more sleep disturbances appear earlier in children who have ADHD,and these changes in sleep patterns are observed before the typical age of an ADHD clinical diagnosis [99].Similarly,among adolescents with ADHD,changes in normal sleep patterns,such as regular daytime napping and later wake-up times,are associated with increased rates of inattention,hyperactivity,and impulsivity [94].Consequences on other behavioral disorders,such as ODD and conduct disorder,are less clear.A longitudinal study followed up on 1420 children for 4—7 years and found that sleep problems predicted increases in the prevalence of later ODD,and in turn,ODD predicted increases in sleep problems over time [88].Despite the limited evidence,screening children and adolescents for unhealthy sleep could offer promising opportunities for reducing the burden of mental and behavioral illness.

An important related question is whether sleep and behavior problems have a reciprocal relationship.An increasing number of studies are examining this in children and adolescents,but results across studies are inconsistent.There are studies showing bidirectional association [81,100— 102] and others f inding no such relationship [103,104].For example,a recent longitudinal cohort study supports a bidirectional relationship: sleep problems in Chinese children at age six were associated with the development of new behavior problems at age 11.5,and vice versa [92].This is in line with results from some [100,102] but not all [81] studies.Quach and collegues reported that a bidirectional relationship existed between sleep and externalizing but not internalizing behavior.Assessing both sleep and behavior in pediatric settings is critically important for pediatric practitioners to identify other problems.Further research is required to fully understand this entwined relationship.

Prevention and interventions

Given the negative consequences of unhealthy sleep,there is a substantial need to identify effective measures to prevent and mitigate childhood sleep problems.At the system/community level,interventions including delaying school start time by just 30 minutes result in signif icantly increased sleep duration [105].A recent study similarly found that delayed school start times could decrease the need to catch up on sleep during weekends [106].In addition to sleeping more,students also reported greater sleep satisfaction and motivation [105],decreased daytime sleepiness and fatigue [107],and less depressed mood [108].In this section,we further discuss evidence-based sleep interventions for children and adolescents on individual levels (Supplementary Table 1).

Nutritional intervention

Dietary intake and sleep are interwoven health behaviors associated with child development and may be amenable to intervention.In line with observational studies,experimental research shows the sleep benef its of improved nutritional intake.Among infants,those who receive iron—folic acid supplementation have longer nocturnal and total sleep duration.Zinc supplementation reduces the length of naps and increased total sleep duration [109].However,there are no apparent sleep benef its of combined iron-folic acid and zinc supplements,suggesting a possible antagonism between iron-folic acid and zinc [109].Additionally,exposure to omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids(LC-PUFA) through supplementation or dietary intervention may improve sleep organization and maturity in infants and improve sleep disturbance in children with clinical-level sleep problems [110,111].However,recommendations for taking omega-3 LC-PUFA to improve sleep outcomes should be taken with caution as this area of study is still inconclusive.Further investigation is also warranted to conf irm the effect of omega-3 LC-PUFA intervention on sleep health in different populations.Furthermore,a recent randomized control trial was conducted on a sample of healthy lean and short children (5.6 years old) and utilized a range of nutritional supplements encompassing 25% of the recommended dietary reference intake for calories,was high in protein,and contained vitamins A,C and D,iron and zinc.Children who took at least 50% of the recommended dose had shorter sleep latency than those with poor adherence,and sleep duration was correlated with increased caloric intake,protein and carbohydrate intake per kilogram [112].

The type and timing of dietary intake may improve sleep—wake function,supporting the concept of chrononutrition.Accordingly,researchers have developed nighttime cereals enriched with sleep facilitators including tryptophan,adenosine-5′-phosphate,and uridine-5′-phosphate for infants and toddlers with sleep disorders.When ingested during night hours,infants with sleep disorders display longer nighttime sleep time,reduced sleep latency and improved sleep efficiency [113].Similarly,earlier introduction of solid foods may improve infant sleep.Compared with infants exclusively breastfed until six months old,those who are introduced to solids at the age of three months exhibit longer sleep duration,less frequent waking at night,and fewer serious sleep problems [114].

Exercise

Exercise has been associated with improvement in sleep health [115,116].Slow-wave sleep is associated with cerebral restoration and recuperation [117] and is important for memory and learning [118].Engaging in 30 minutes of high-intensity exercise signif icantly elevates the proportion of slow-wave sleep,increases sleep efficiency,and shortens sleep onset latency in school-aged children [119].In a study of adolescents,those who ran 30 minutes every weekday morning for three consecutive weeks demonstrated improvements in both objectives (e.g.,increased slow-wave sleep and decreased sleep latency) and subjective (e.g.,enhanced sleep quality,mood,and concentration and reduced daytime sleepiness) sleep measures [120].These f indings suggest that promoting the involvement of children and adolescents in organized sports leagues or simply playing outside are potentially feasible and low-cost methods to mitigate sleep problems and subsequent adverse health outcomes.

Cognitive–behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I)

CBT-I,the f irst-line treatment for adulthood insomnia,has been unitized to improve sleep health in adolescents with and without diagnosed insomnia [121— 123].Multimodal CBT-I consists of a combination of cognitive therapy(restructuring negative sleep beliefs or reducing excessive worry about sleep),behavioral interventions (e.g.,sleep restriction and stimulus control),educational interventions(e.g.,sleep hygiene) and relaxation (e.g.,progressive muscle relaxation,guided imagery,and/or breathing techniques).CBT-I modifies the patterns of thinking and behavior underlying sleep disturbances,such as poor sleep hygiene,irregular sleep—wake schedules,delayed bedtimes,pre-sleep hyperarousal,and maladaptive sleep-related cognitions[122].For early childhood,the cognitive component focuses on parental education programs as well as on altering sleeprelated cognitions and beliefs of parents regarding the sleep of their child [124].There are fewer studies on children and adolescents compared with the CBT-I studies on adults.However,emerging evidence has shown improvement in sleep latency,efficiency and quality,and wake-after-sleep onset after 4—12 weeks of CBT-I in children and adolescents,despite mixed f indings of several sleep variables (e.g.,total sleep time) [121— 124].In terms of delivery modality,self-administered digital CBT-I may overcome staffand cost constraints with a comparable sleep effect [121].However,further high-quality RCTs are needed to test the cost-effectiveness of different CBT-I features,such as delivery format(i.e.,individual vs.group,digital vs.face-to-face),length of treatment (i.e.,short vs.long) and selection of CBT-I components.

Others: aromatherapy,acupressure,mindfulness

Researchers have begun investigating the potential use of aromatherapy among infant populations,though there is a lack of evidence on children and adolescents.Specif ically,the use of lavender-scented lotion by mothers on their infants is associated with increased sleep duration and fewer nighttime sleep disturbances [125].Similarly,infants bathed in lavender bath oil cry less prior to sleep and spend more time in deep sleep [126].

Acupressure therapy utilizes pressure and massage to stimulate the body [127].Among a sample of adolescents with insomnia,those who receive acupressure stimulation during sleep via a wrist device demonstrate a signif icant increase in sleep duration as well as reductions in sleep onset latency,wake after sleep onset,and stage 2 sleep [128].

Finally,mindfulness has been identif ied as a potential nonpharmacologic intervention for better sleep health in children and adolescents.A middle school curriculum that combined Tai Chi with mindfulness practice demonstrated improved self-reports of sleep quality and sleep latency in students [129].Among adolescents,similar improvements in sleep quality are linked to mindfulness-based treatments such as mediation practices [130] and structured programs including mindfulness-based stress reduction,yoga,and group discussion [131].A potential mechanism of action is rumination: mindfulness reduces rumination,which is linked to poorer sleep quality,thus improving sleep quality [132].

Gaps in literature,future directions,and implications

This review discusses the current knowledge available regarding the adverse health consequences associated with poor sleep health,and potential interventions to prevent and mitigate these negative physical,mental,and behavioral health problems requiring further research.The majority of published articles on the topic of childhood and adolescent sleep utilize cross-sectional study designs.Additional research employing cohort or longitudinal study designs may elucidate the causality of these relationships.Furthermore,a recent concept analysis [133] calls for the employment of a comprehensive methodology in investigating the impact of sleep quality on children,which includes assessing how certain events (e.g.,school breaks) may inf luence childhood sleep.

Prior research mainly focused on individual sleep characteristics in relation to health outcomes.However,sleep problems have multidimensional manifestations that often coexist in the pediatric population [2,17].Thus,using big data techniques to def ine high-risk sleep phenotypes (combination of sleep duration,quality,and circadian rhythm) that are associated with increased pediatric morbidity and mortality will inform more meaningful interventions for sleeprelated health conditions.Also,sleep is often comorbid with other health conditions (e.g.,depressive symptoms [88]) in inf luencing childhood functioning and diseases.Thus,symptom clusters should be considered in assessments and interventions for sleep-related health outcomes.

In terms of prevention and intervention techniques,current research is not sufficient to demonstrate and support their efficacy.Furthermore,increased focus on treatments that are not only effective but also simple,affordable,and easily accessible,such as exercise,are needed to ensure widespread use.Due to the importance of sleep on physical,mental,and behavioral health during developmentally sensitive periods [2,17],the availability of such prevention and intervention strategies are critical in improving child and adolescent health.Community-based trials are warranted to test the efficacy of multi-level interventions in real-life settings,instead of highly-controlled clinical trial conditions.

In the context of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic,recent studies have shown that children and adolescents are subject to sleep changes [134].Promoting sleep health should be integrated into strategies to mitigate the effects of home conf inement on children’s mental health during the COVID-19 outbreak [135].

Finally,given the signif icance of child sleep,it is important to highlight both practical and policy implications.Practical implications may focus on risk factors attributed to sleep as well as consistently assessing sleep quality in pediatric populations [133].Policy implications are especially important to address the public health issue of child and adolescent sleep.As early as 2014,the American Academy of Pediatrics proposed the delay of school start times to extend child and adolescent sleep duration [136].More recently,the American Academy of Nursing proposed addressing screen media practices to reduce sleep disturbances and adverse sleep outcomes [137].Globally,the Ministry of Education of China launched a policy regarding delaying school start times for adolescents and enhancing sleep health,and this policy showed great benef its not only for child sleep health but also for physical and mental health as well as academic performance [138].Given that there are many risk factors related to child sleep and given that there have been benef its from interventions targeted to these risk factors,we hope that future policies will continue to address these issues.

Conclusions

In conclusion,a variety of aspects of children’s growth and development is affected by childhood sleep.Considering that sleep problems are widespread among children of all age groups as well as their negative consequences on children’s physical and mental wellbeing,understanding and developing potential prevention and intervention efforts is important to guide future research and healthcare practices to mitigate sleep problems both in childhood and in later life.

Supplementary InformationThe online version contains supplementary material available at https:// doi.org/ 10.1007/ s12519-022-00647-w.

Author’s contributionLJ conceptualized and designed the study,drafted the article,and revised it critically.JX drafted the article,and revised it critically.PS and RE drafted the article.LT,WG and JF revised the manuscript critically.All authors approve of the f inal manuscript to be published.

FundingThis study is funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Development (NIH/NICHD R01-HD087485).During the study,WG and JF were supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos.82073568,82071493),Innovative Research Team of High-level Local Universities in Shanghai (Nos.SHSMUZDCX20211100,20211900),Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (No.2018SHZDZX05),and Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (Nos.2022XD056,2020CXJQ01).

Data availabilityData sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethical approvalNot applicable.

Conflict of interestNo f inancial or non-f inancial benef its have been received or will be received from any party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.Author Fan Jiang is an Associate Editor forWorld Journal of Pediatrics.The paper was handled by the other Editor and has undergone rigorous peer review process.Author Fan Jiang was not involved in the journal's review of,or decisions related to this manuscript.The authors have no conf lict of interest to declare.

World Journal of Pediatrics2024年2期

World Journal of Pediatrics2024年2期

- World Journal of Pediatrics的其它文章

- Growth and development of children in China: achievements,problems and prospects

- Childhood sleep: assessments,risk factors,and potential mechanisms

- Risk factors for long COVID in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- SARS-CoV-2 variants are associated with different clinical courses in children with MlS-C

- NLRP3 activation in macrophages promotes acute intestinal injury in neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis

- Exploration of pathogenic microorganism within the small intestine of necrotizing enterocolitis