Staying in “African Time,” Watching the Clouds Roll by

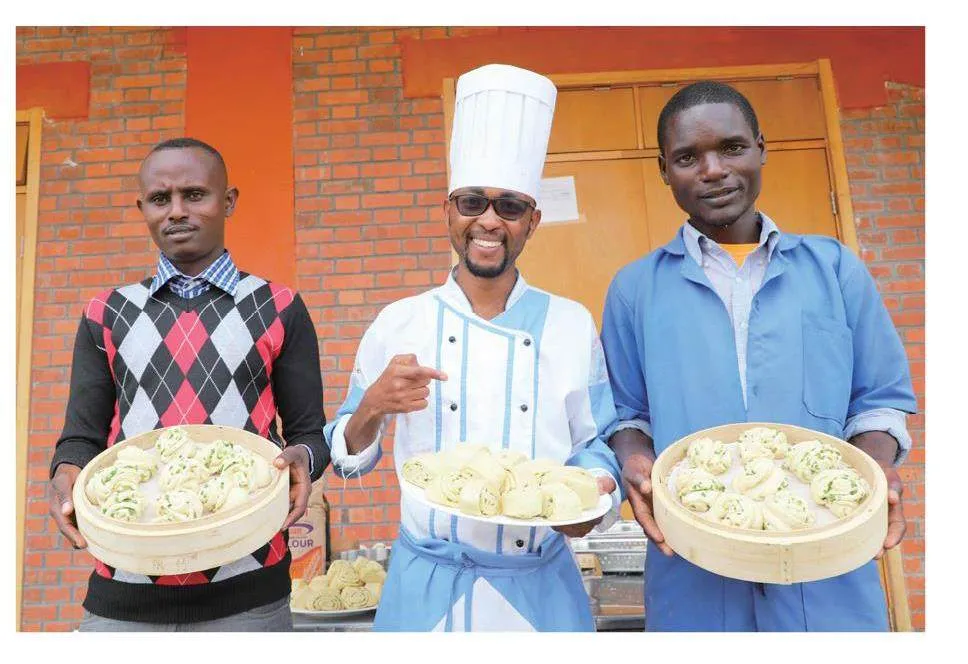

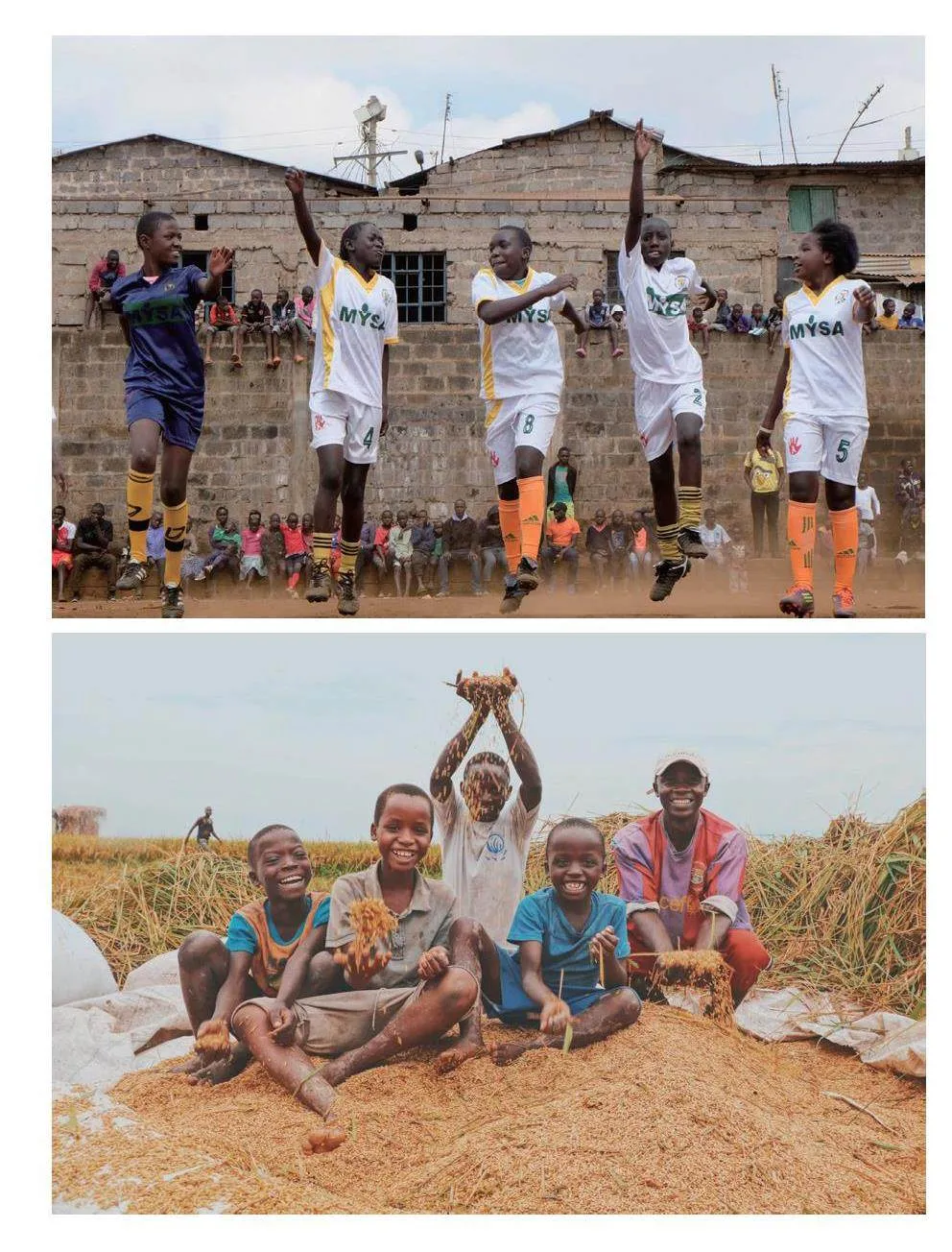

A Chinese journalist spent 1,123 days flying to 30 African countries and regions to meet presidents, believers, soldiers, and passersby, to explore ruins, homes, castles, and lighthouses, and to witness the starry skies, rift valleys, deserts, and oceans. He immersed himself in the sharp present and at any moment stepped into the majestic history, constantly approaching suffering and struggle, yet always finding hope and loveliness, and always believing: the infinite distance, countless people, are all related to you and me.

Lyu Qiang

Lyu Qiang is a travel writer, host, and photographer. He has traveled to nearly 60 countries and regions around the world, served as a reporter for the People’s Daily Africa Center branch for three years, covering news in the sub-Saharan African region, and visited 30 African countries and regions.

During a major international forum at home, I received a preview copy from the publisher. Despite a packed forum schedule and evening preparations for the next day’s events, I was immediately captivated upon opening it. For a bookworm who reads dozens to hundreds of African studies textbooks each semester to update numerous courses and squeeze in time for research and writing, this book, which quickly engaged my reading interest, not only offers the readability and profound meaning demanded by general readers but also possesses distinct reality and research value.

The author humbly calls his book “somewhat like a travelogue,” which is based on three years of continuous travel, observation, and visits across 30 countries in Africa, grasping historical lessons or questioning sharp realities at every stop in each country and in every inquiry made. It’s like a beam of light penetrating deeper into history, powerful text, and exquisite images complementing each other, making the book “sparkle” and showcasing the unique sharpness, sensitivity, and profound human concern of contemporary outstanding Chinese youth. For someone like me, who has long studied Charming Great Africa, I eagerly anticipate my students reading this book because it fully utilizes intuitive and emotional power to gain insights that the typically stiff and formal “theoretical books” listed by teachers rarely provide, especially on themes common across nations, beyond the African continent, and throughout the human world, for instance, the dynamic text that strings together the African characters, echoing historical themes or contemporary resonances across different regions of the world with the African continent.

The content related to South Africa, I believe, is the most splendid part, obviously resulting from the author’s compelled stay in South Africa under control measures, thus leading to deeper thought and observation. Chinese media is not lacking in narratives about South Africa, whether during its apartheid regime or the birth of the new South Africa under Mandela’s leadership, with recent topics dominated by South Africa’s “decline.” What’s novel about this book is that, it revisits the historical evolution of the Dutch-descendant whites, English-descendant whites, and blacks’ triangular relationship with a journalist’s keen perspective, analyzing how today’s narratives from all three sides shelve the not-so-distant bloody memories. Without the victorious side violently erasing the opponent and their historical traces and deliberate memorial arrangements, it gradually realizes coexistence on the “God-blessed” South African land, “by enriching the content to dilute what was once mainstream narrative,” achieving “a dialectical existence of history.” How contemporary people face history with a reconciling attitude towards the future is not just a lesson for South Africa, which once reached the pinnacle of apartheid. Looking around the world today and under multiple conflict hotspots, the continuous groans and laments of life, this book is enough to inspire Chinese readers and the whole world. It encourages humans, whose identity differences are constantly reinforced by social media, to learn the attitude of coexistence and peace from South Africans, and to protect and build a habitat of mutual dependence jointly.

If this is the greatest contribution South Africa has made to the world, we thank Lyu Qiang for presenting this opportunity to understand and scrutinize South Africa with his extremely patient and meticulous sensibility to the Chinese-speaking world. Indeed, understanding the vast African continent also requires deep immersion to listen to Africa’s voice -- which is even polyphonic and contains multiple contradictory voices, right? When many Western media outlets and scholars often get entangled in many African countries’ control over social media, and intentionally or unintentionally aim their criticism at China for providing financial and technical support for these countries’ digital infrastructure, Lyu Qiang provides a multifaceted observation of the rapidly occurring information revolution in Africa, seeing the eagerness of leaders to achieve the “2040 vision” sooner, as well as recognizing that the push digitalization gives to each country’s economy isn’t as ideal and rapid as expected. It also comes with the development and control tug-of-war of the E-era.

Thanks to the author for spending three years “staying in African time, watching the clouds roll by, and the stars shift.”