前车之鉴:某些演出“一轮游”的缘由

说起来有点奇怪,有些人你只会在丧礼中遇见。几年之前,在我老家的一个严肃的告别仪式上,我和一位高中老同学重逢,一下子拾回多年前的友谊。但是,在聚过几次后,我们又再次失联。

几周前,我们又一次相遇——你猜得很对,是另一场严肃的丧礼上——所幸,这一次我们交换了更为全面的联系方式。在接下来的几天里,我们交流了不少冷笑话以及一些好问题,更有几次电话中的畅谈。可是,我们一直都没有机会讨论她早先提出的一些疑问。帕蒂(Patty)和我在青年时代都踊跃参与各种音乐和戏剧的课外活动。她也知道,如今的我除了撰写演出评论以外,还曾参与过一些戏剧与歌剧项目的创作或制作过程。她的问题是:因为我曾参与其中,当我看演出时,是否会有不同的视角和观点?

对不起,帕蒂,我们一直都没有抽出时间探究这个问题,但是,现在我有答案了。事实上,正因为我经历过几台舞台制作都是从零起步,直至面向公众举行首演,所以现在我明白为什么很多此类项目会一败涂地。

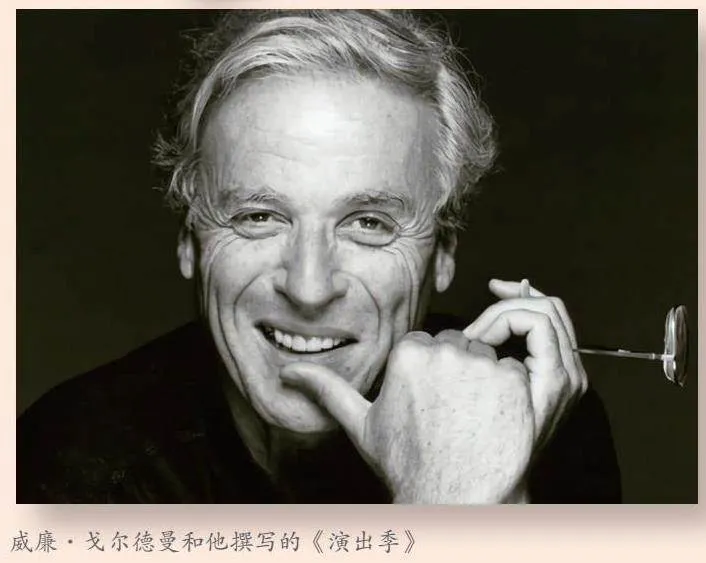

这其中的大部分因素其实是根深蒂固的,所以你未必会留意到某些细节,但是威廉· 戈尔德曼(William Goldman)极具洞察力,把这些情况清晰地用文字记录了下来。在这位畅销小说家与奥斯卡获奖编剧说出精辟的金句去描述好莱坞之前(“没人能知道任何事”,意思是没有一位艺人或监制能够刻意解释出一部电影为何风行一时),他曾经深度研究过百老汇舞台上失败的例子。在他撰写的《演出季》(The Season )一书中,戈尔德曼(他自己就曾是一位失败的舞台编剧)总结出所有失败的舞台制作都是出于五种问题中的某一种或几种。

或许是剧本写得烂,或者是戏演砸了;也有可能是该制作还未准备充分却不得不匆匆公演(当然这样就更暴露出剧本或演员的短板之处),又或者是每周的运营成本过高(这明显要归咎于制作人)。但是,最有趣的失败原因是:主创团队中的每一个人其实都在创作各自的、截然不同的舞台秀——这一点,尤其当你曾经亲眼看见过,当它再次出现时, 你一眼就能发现。

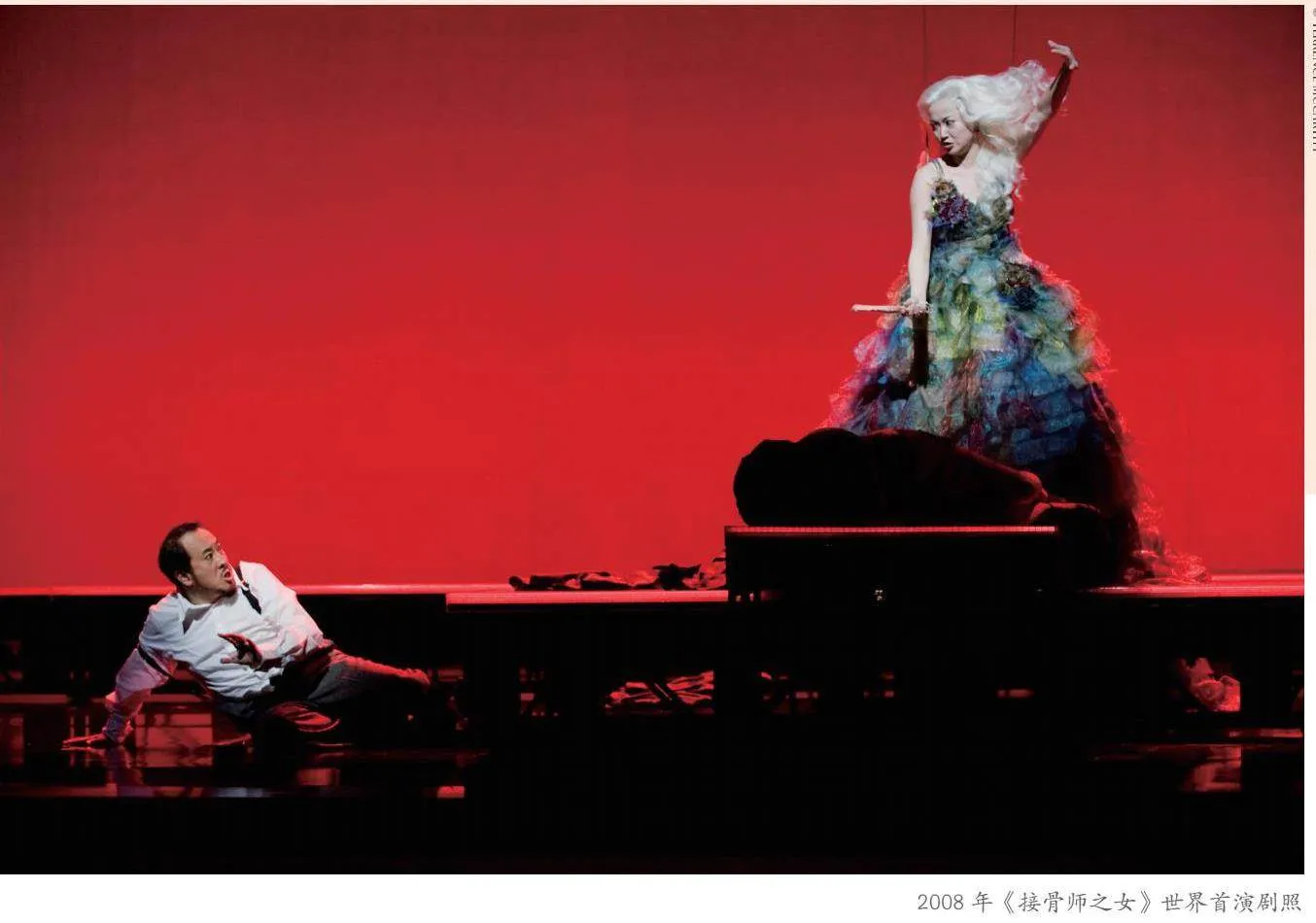

早在2008 年,我有幸参与到《接骨师之女》(The Bonesetter’s Daughter )的世界首演制作中。作曲家是斯图尔特· 华莱斯(中文取名惠士钊), 编剧是谭恩美,她负责将自己的同名小说改编成歌剧剧本。他们俩曾多次游历中国大江南北,其中有两趟我参与其中,并介绍了当地的音乐家给他们, 让他们感受到中国城市与乡村的氛围。两人都完全沉浸在故事情节中,而剧本与总谱都含有叙事性精华:这两位艺术家的合作程度十分专业,成果可谓是音乐与文本的完全融合,引人入胜。

可惜这部歌剧在登上旧金山歌剧院的舞台时, 却变得困难重重。一直以来,导演陈士争都把谭恩美的故事赋予神话式的叙事比重——这种处理手法在一定程度上是相当合理的。但是陈士争想缔造的神话却不是谭恩美心目中的;排练期间,舞美设计就分散了故事自身的张力。很多观众都质疑为什么一个关于三代中国女性的家庭故事里会有那么多杂技演员的出现?舞台上的那几条龙在上面干什么?

然而,《接骨师之女》出现的问题与《变蝇人》(The Fly )相比又是那么的微不足道。曾几何时,《变蝇人》这部歌剧被认为是我毕生看过的最糟糕的歌剧(后来我考虑再三,甚至不想给它冠以任何“第一” 的头衔,哪怕是倒数的)。

《变蝇人》在洛杉矶歌剧院的演出档期刚好与旧金山的《接骨师之女》撞上。要是用好莱坞术语来形容《变蝇人》,应该是“高概念”(high-concept)①。基本上,歌剧的故事根植于大卫· 柯南伯格(David Cronenberg)1986 年拍摄的经典同名电影,由霍华德· 肖(Howard Shore)作曲(作曲家也为同名电影谱写了原创配乐),编剧是美籍华裔作家黄哲伦(他曾与肖及柯南伯格合作过1993 年拍摄、改编自舞台剧的电影《蝴蝶君》)。

为了《变蝇人》,我从旧金山特别飞往洛杉矶。正因为在旧金山看到的是谭恩美与惠士钊两人的合作无间,我在洛杉矶歌剧院看《变蝇人》的时候, 简直目瞪口呆——大部分的歌词与旋律不太吻合, 好像是在反刍模仿巴托克的某些音乐元素。看完演出不久,我找到黄哲伦,问问他这部歌剧究竟发生了什么。

“你跟霍华德· 肖有没有交流过彼此的想法?” 我问道。

“没那么多交流的时机,”他很坦白,“肖的电影配乐往往都是以浪漫的长句组成的,因此我写的歌剧唱词就依据了这种风格。但是,当肖开始谱写这部歌剧时,他改变了意图,要当一位‘严肃’的现代作曲家。”

对于《变蝇人》的失败,我们还要将柯南伯格考虑进来。我们一眼就能看出,他缺乏舞台剧执导经验。无论是何种艺术载体,叙事手法中的很多元素大体都能很好地相互交替转换。比如说,电影与音乐都将时间作为交替的媒介。可是,空间在叙事手法中的交替,则完全不一样。而且,坦率地说, 柯南伯格对于如何处理舞台上的合唱团,简直是无从下手。

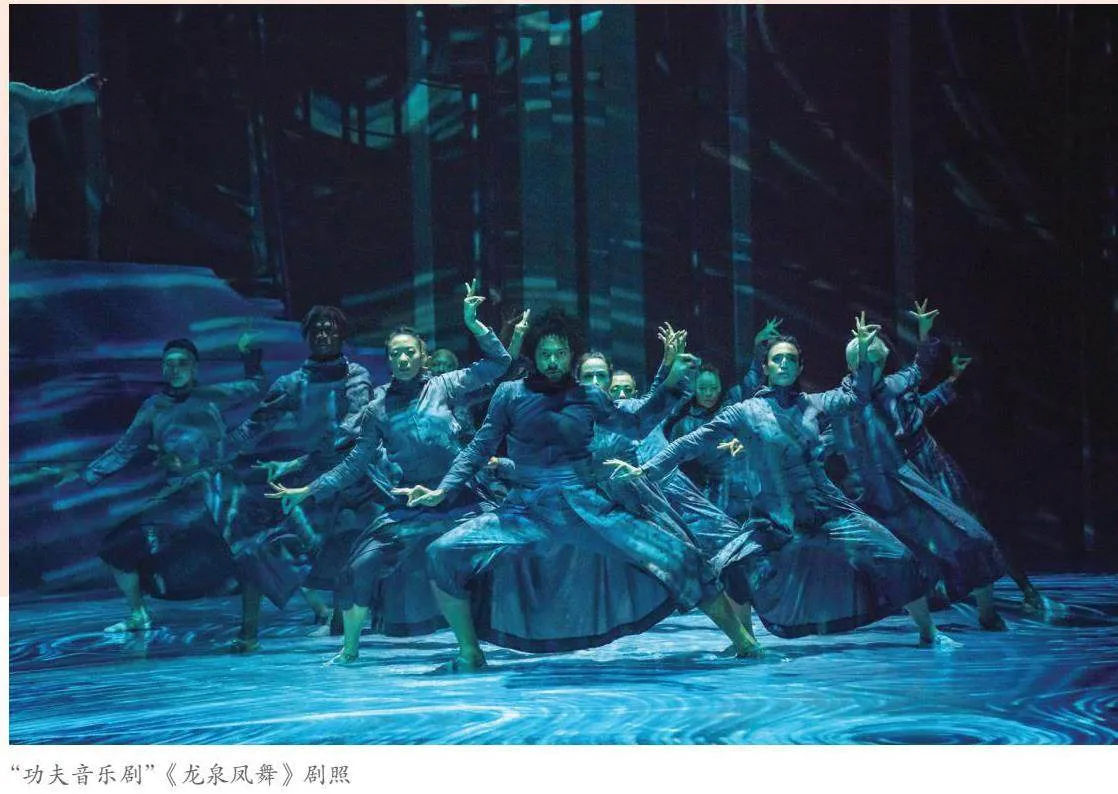

作为一个彻底的失败个案,《变蝇人》的“地位” 在2019 年被《龙泉凤舞》(Dragon Spring Phoenix Rise )彻底取代,这是纽约一座新的、灵活的艺术展演空间“棚屋”(The Shed)真正浮夸的处女作, 是一场由导演陈士争(再一次榜上有名!)与电影《功夫熊猫》的编剧乔纳森· 阿贝尔(Jonathan Aibel) 和格伦· 伯杰(Glenn Berger)联合创作出的大秀。该剧被描述为一部由国际现代舞大师阿库让· 汉(Akram Khan)和功夫名家张俊担任编舞和动作指导的“功夫音乐剧”,但在舞蹈性和武术性这两方面都以惊人的失败而告终。“音乐”部分仅由三首歌曲组成,其中没有任何一首能够推进故事的发展(甚至可以说是与故事毫无关联)。《纽约时报》对此评论的标题是“瞪大眼睛,头脑宕机”。

但是,在这么多可供指责的问题中,有一个是压倒一切的:剧本。正如编剧们在《功夫熊猫》中所做的那样,故事有一种向前推进的势头,但需要其他元素赋予动力。和陈士争以前的舞台史诗制作一样,《龙泉凤舞》上至天花板下至地板,所有的空间都被演员们的动线填满。故事是横向的,舞台是纵向的——就像一部由太阳马戏团上演的动作片。基于上述的问题,《龙泉凤舞》没任何一丝机会可以成功。

用不了太久,你就会察觉到那些征兆。每当众星云集的主创队伍第一次聚集在一起时,你就必须开始提防。很有可能因为这些人都太成功了,所以他们就不愿意听取他人的意见,更何况这类制作中通常没有一个核心人物来执掌创作的全过程。

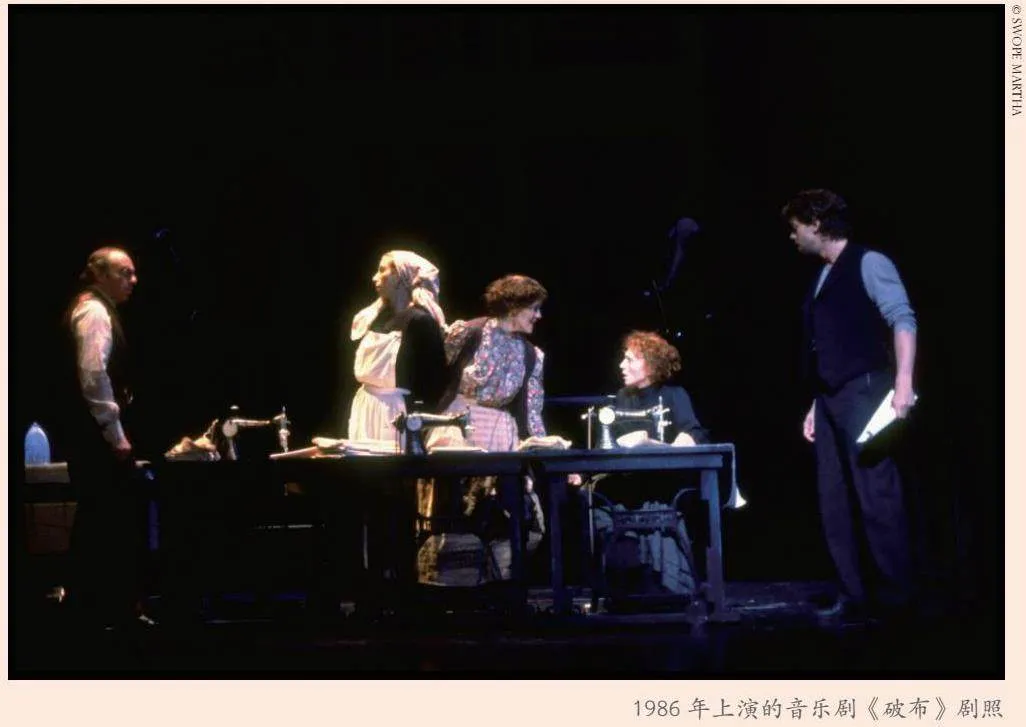

然而,在我个人排名的失败剧目排行榜中,位居榜首的是1986 年的音乐剧《破布》(Rags ),由约瑟夫· 斯坦因(Joseph Stein,他写了《屋顶上的提琴手》)负责音乐,斯蒂芬· 施瓦茨(Stephen Schwartz,创作了《福音》《魔法坏女巫》)和查尔斯· 施特劳斯(Charles Strause,创作了《安妮》)作词。《破布》总共只在百老汇上演了四场;我是最后一场日场的观众。

当年,许多人指责该剧的主演特蕾莎· 斯特拉塔斯(Teresa Stratas),一位才华横溢但喜怒无常的歌剧歌唱家,埋怨她没有演出音乐剧的专业经验。但斯特拉塔斯并不是问题所在。主创们沉浸在各自的世界里工作,没有人负责统领,这才是这部音乐剧致命的缺陷。

说实在的,情况有点复杂。《破布》显然没有准备好就匆匆上演——后来,规模缩小的复排版的效果更为成功。另外,初版的制作显然太贵了。早在20 世纪80 年代中期,它每周的运营成本就超过了百万美元。

事实上,我会保留《破布》在我的榜首,是因为回到《演出季》一书中去看,对照威廉· 戈尔德曼提到的百老汇各种失败原因,它赢得了大满贯。

Strange as it seems, some people you run into only at funerals. Several years ago, I was reunited with a high school friend at a solemn gathering in our hometown. We fell back into our old groove pretty smoothly, but after getting together a couple of times we lost touch.

A few weeks ago, we met once again—at, yes, another funeral—though this time I think we were better about exchanging contact information. Over the next few days, we traded many bad jokes and a few good questions, several of which we discussed at length over the phone. But one of her initial queries we never discussed. Patty and I had both been heavily involved in music and theatre in our youth, and she knew that, in addition to writing about performancesnow, I’ve also been involved in the creation of several theatre and opera projects. Did that, she asked, make me watch performances any differently?

Sorry we didn’t get around to that, Patty, but I now finally have an answer. Indeed, seeing first-hand what goes into creating stage productions has taught me a lot. Now I know why most shows fail.

Much of this becomes so ingrained that after a while you stop noticing the details, but William Goldman had the insight to put it clearly into words. Long before the bestselling novelist and Oscar-winning screenwriter made his famous observation about Hollywood (“Nobody knows anything,” meaning no artist or producer can honestly explain why a film is a hit), he did exactly the opposite for Broadway. In his book The Season , Goldman (himself a failed playwright) explained that all failed plays fail in one of five ways.

Plays can either be badly written, or badly performed. A show might open before it’s ready (whichwould also emphasize some bad writing or acting), or the weekly operating costs might be too high (which is clearly the fault of the producers). But the most interesting cause of failure, once experienced, becomes unmissable when you see it happen again: the collaborators have been working on entirely different shows.

Back in 2008, I was involved in the creation of The Bonesetter’s Daughter by composer Stewart Wallace with a libretto by Amy Tan (based on her novel). The two of them traveled together extensively in China; twice I was there on hand to introduce them to musicians and to show them the difference between urban and rural settings. Their full immersion into the story’s narrative trail eventually translated to the page: the two became professionally inseparable and ended up spinning a mystifying mind-meld of music and text.

The show became a bit problematic, though, once it got to the stage at San Francisco Opera. Director Chen Shi-Zheng had always viewed Amy’s story in mythic proportions—a thoroughly legitimate approach, as far as that goes. But Shi-Zheng’s myths were not Amy’s, and the visual elements soon distracted from the story. Why, many observers wonderedat the time, did essentially a domestic tale of three generations of Chinese women have so many acrobats on stage? And what were all those dragons doing there?

Bonesetter ’s problems, however, were nothing compared with those of The Fly , which for a time I considered the worst opera I’d seen. (I’ve since reconsidered, because I didn’t want to give it the honor of being number one.)

Appearing at Los Angeles Opera at the same time Bonesetter was in San Francisco, The Fly was what they call in Hollywood “high-concept.” It was essentially a stage retelling of director David Cronenberg’s 1986 film, with music by Howard Shore (who scored the film) and libretto by David Henry Hwang (who had worked with Cronenberg and Shore on the 1993 film of his play, M. Butterfly ).

Flying to LA from San Francisco, where I’d seen Amy and Stewart still in close tandem, I sat listening and watching The Fly in total disbelief. Very few lines of dialogue actually fit with the music, which seemed to be regurgitating Bartok. Shortly afterward, I approached David Hwang to ask what happened.

“Did you and Howard even discuss this show?” I asked.

“Not so much,” he admitted. “He usually composes long romantic lines in his film music, so that was the kind of dialogue I wrote. But once he started writing an opera he wanted to be a ‘serious’ modern composer.”

Then there was Cronenberg, whose inexperience working on stage was immediately palpable. Many elements of storytelling translate quite well across different forms, since both film and music use time as a medium of exchange. Space, however, is a completely different thing. And also, to put it bluntly, Cronenberg had absolutely no idea what to do with a chorus.

But as an utter failure, The Fly was knocked off its pedestal in 2019 by Dragon Spring Phoenix Rise , the truly pompous inauguration of The Shed, one of NewYork’s more flexible performing arts venues. Director Chen Shi-Zheng (again!) helmed a production written by Jonathan Aibel and Glenn Berger, writers of the film Kung Fu Panda . Described as a “kung fu musical,” with choreography by Akram Khan and martial artist Zhang Jun, the show failed spectacularly at both. The “musical” component consisted entirely of three songs, none of which advanced (or indeed, had any relationship to) the story. The headline of the New York Times review was “Eyes Wide Mind Numb.”

But with so many places to point fingers, there was a single overriding problem: The script, as the writers had done in Kung Fu Panda, had a certain momentum begging to be pushed forward; Shi-Zheng, as with his previous stage epics, set out to fill his space with floor-to-ceiling activity. The story was horizontal, the staging vertical—an action film as staged by Cirque du Soleil. It never had a chance.

After a while, you can see the signs. Whenever star-studded creators come together for the first time, consider yourself warned. Odds are high that the individuals are too successful to listen to others, and that no central vision will be guiding the proceedings.

Topping my personal Pantheon of failed projects, though, is Rags , a 1986 musical written by Joseph Stein (who penned Fiddler on the Roof ), with lyrics by Stephen Schwartz (Godspell, Wicked) and Charles Strause (Annie). It ran on Broadway for only four performances. I was in the audience for the final matinee.

At the time, many people blamed the show’s star, Teresa Stratas, a brilliant if temperamental opera singer with no professional experience with musicals. Stratas was not the problem. The fatal flaw was that the creators were working in their own respective worlds and no one was in charge.

Actually, it was a bit more complicated. Rags clearly wasn’t ready—later, more modest reworkings of the show have proven more successful. And the show was obviously too expensive; back in the mid-1980s, it had a weekly running cost of more than million dollars.

In fact, I’ll keep Rags at the top of my list simply because, looking back at The Season , as a Broadway failure it was a full William Goldman trifecta.