‘The Northern chemist’—Truth behind the stereotype in the British scientific elite?

Erzsébet Bukodi and John H Goldthorpe

University of Oxford,UK

Abstract In a prosopographical study of the British scientific elite,defined as Fellows of the Royal Society born since 1900,chemists were found to be distinctive in their social origins and schooling,being more likely than Fellows in other fields to come from relatively disadvantaged class backgrounds and to have attended state rather than private secondary schools.In thinking of possible explanations,we called to mind the student stereotype of ‘the Northern chemist’.Could this give some indications of how it should come about that those chemists who enter the scientific elite—a small minority—tend to differ from other elite members in the ways in question?Our more detailed analyses of the biographies of elite chemists,comparing those of different class origins,point to the following conclusions.The Northern chemist was a male stereotype,and chemists prove to be more predominantly male than other members of the scientific elite.Young people,mainly male,often growing up in industrial areas of the North of England (or in Wales) and in families whose male members were in manual work,were particularly likely to develop an interest in chemistry rather than in other sciences,and it was in chemistry that state education gave them their greatest comparative advantage over those privately educated.Generalising from these analyses,we suggest that a larger pool was created in chemistry than in other scientific fields of people who were of relatively disadvantaged social origins and state educated,and that this difference was then maintained through into the social composition of the small number of chemists who eventually gained elite status.

Keywords Scientific elite,Royal Society,prosopography,chemistry

1.Introduction

In a recent paper (Bukodi et al.,2022),we have reported on research into the social class origins and secondary schooling of the UK scientific elite,understood for the modern period as Fellows of the Royal Society born since 1900.1The research follows a programme previously set out (Bukodi and Goldthorpe,2021) for the grounding of elite studies in prosopographies—collective biographies—of their members.

We have obtained relevant data on the scientific elite,as we define it,from a variety of sources.For deceased Fellows,we rely mainly on the Royal Society’s excellentMemoirsand on theDictionary of National Biography;but we have also drawn on other biographical material that can be found on the web.For living Fellows,we rely mainly on results from a web-based questionnaire sent out in late 2020 to all of those falling into our target population,for which we achieved a response rate of almost 70%;but also,and especially for nonrespondents,we have consultedWho’s Whoand Debrett’sPeople of Todayand have again sought out web material.Overall,we obtained data adequate for our purposes for 1691 of our target population of 2112 Fellows or,that is,an 80%coverage.In view of this,we have taken Fellows on whom we do have full information as being representative of our target population with the possibility of only very minor,if any,biases occurring.We do not therefore apply any tests of statistical significance to our results.

In the light of other elite studies,certain of our findings are not at all surprising.Over the period covered,members of the scientific elite have been disproportionately recruited from among individuals of more advantaged class origins—UK National Statistics Socio-economic Classification Classes 1 and 2 (NS-SEC)—and from among those privately educated.We do,though,also observe that,within Classes 1 and 2,Fellows are clearly more likely to have come from professional rather than from managerial families and,in more recent cohorts,from professional families in which at least one parent was engaged in an occupation involving scientific,technical,engineering or mathematical (STEM)knowledge and expertise.Also,Fellows from professional families,if privately educated,were more likely than their counterparts from managerial families to have attended day rather than boarding schools.One further finding was,however,of a quite unexpected kind.Across all birth cohorts,Fellows who werechemistsshowed,in both their class origins and their schooling,a notable degree of deviation from the general pattern.

As regards class origins,only 34% of chemists came from higher professional and managerial families (NS-SEC Class 1),a lower proportion than Fellows in any of the other nine subject areas distinguished by the Royal Society,in which the corresponding proportion ranged from 41 up to 55%.This difference was then largely offset in the following ways.First,16%of chemists,a larger proportion than of Fellows in any other subject area,came from the families of small employers—mainly farmers,builders or workshop owners—or from those of self-employed men,mainly in skilled trades (NS-SEC Class 4).Second,5% came from families headed by foremen,factory supervisors or lower-level technicians (NS-SEC Class 5).2And,third,a further 16% came from the families of wage-earning,mainly manual workers (NS-SEC Classes 6 and 7).That is to say,in all,some 37%of chemists could be regarded as being of relatively disadvantaged class origins and also as having grown up in social milieux in which manual work predominated.Among Fellows in the other subject areas,the corresponding proportion ranged from 31%down to as low as 22% (Bukodi et al.,2022).

As regards schooling—and focusing on Fellows whose schooling was in the UK—only 36% of chemists had been to private schools,while among Fellows in the other subject areas this proportion ranged from 39 to as high 57%.And,correspondingly,it was among the chemists that the highest proportion of Fellows was found who had attended state schools (i.e.,grammar,technical or,among those in the youngest birth cohorts,comprehensive schools).3This was the case with 57% of chemists as compared with the corresponding proportions for Fellows in other subject areas ranging from 55 down to 39% (Bukodi et al.,2022).4

These results were intriguing.Research has previously been carried out (Xie,1992) into the social origins and education of scientists working in different fields—showing in fact a broad homogeneity apart from a distinctive tendency for individuals of farm origins to work in biology.But in the history of studies of stratification within science (e.g.,Cole and Cole,1973)and,more specifically,of the formation of scientific elites (e.g.,Zuckerman,1977),the possibility of differences in the underlying processes across fields has attracted little attention.The case of British chemists would therefore seem to be one meriting further investigation.

As a starting point,what,perhaps unworthily,came to mind was the student stereotype of ‘the Northern chemist’: that is,a man—not a woman—seemingly somewhat out of his depth socially,dour and recessive.Could this stereotype,taken from the student level,provide any hints as to the nature of the social processes that result in the small minority of all chemists who enter the scientific elite varying,to a non-negligible degree,in their class backgrounds and in their schooling from members of this elite working in different fields?

In seeking to answer this question,we focus on chemists coming from the two class backgrounds in regard to which,as noted,the most marked differences arise from others in the scientific elite:that is,on those of higher professional and managerial—NS-SEC Class 1—origins and those of relatively disadvantaged—NS-SEC Classes 4–7—origins.The former account for 87,or 34%,of the total of 255 chemists included in the scientific elite on whom we have biographical information,and the latter for 82,or 32%.Our two main concerns are then the following.

First,how far is there an association between class origins and geographical origins—are chemists from less advantaged social origins more likely to be northerners? Second,are there differences between chemists,associated with their class origins,in how their interest in chemistry originated,as in the contexts of their families and schools,and in how they came to study chemistry in moving on to university?In this latter respect,we draw on the cases of those chemists for whom we have been able to obtain more detailed biographical information of a relevant kind:that is,for 38 of the 87 of Class 1 origins and 49 of the 82 of Classes 4–7 origins.

Before moving on to these questions,one preliminary point may be made on gender.Chemistry has often been seen as an area of science in which women are especially poorly represented,and especially at higher levels.Although,as Rayner-Canham (2008) shows,there were in fact from the mid-nineteenth century onwards some hundreds of women working as chemists,and members of the Chemical Society and/or of the Royal Institute of Chemistry,these women were very largely confined to supportive roles and rarely gained access to positions of any eminence.Shortly after the end of World War II,the Chemical Society published a collection of 16 biographies of eminent British chemists born between 1830 and 1880 (Findlay and Mills,1947),all of whom were men.The representation of women among the chemists in our scientific elite of Fellows of the Royal Society born since 1900 is then of some interest.

Our target population of Fellows numbered 2112.Of these Fellows,155,or 7%,were women.Of the 1691 Fellows for whom we were able to obtain information on their class origins and schooling,125 were women or,again,7%.However,of the 255 chemists,only 12,or less than 5%,were women.There is,in other words,some indication of greater male dominance among the elite chemists than among the elite scientists as a whole.In this context,at least,the student stereotype of the Northern chemist as being male may not be all that misleading.5

2.Geographical origins and social origins

If we compare the places of birth of elite chemists with those of elite scientists in other subject areas across the nine official English regions,plus Wales and Scotland,6no very distinctive tendency appears for chemists to be more often born in the North-East,the North-West and Yorkshire and Humberside than elsewhere.Chemists are indeed more likely to be northerners than elite scientists in biological fields with medical and health connections—38% as against 25%—with whom they also contrast most sharply in their class origins and schooling(see note 4).But other biologists—biochemists,structural biologists and molecular cell biologists—are 39%northerners,with mathematicians,astronomers and physicists not all that far behind the chemists at 32%.

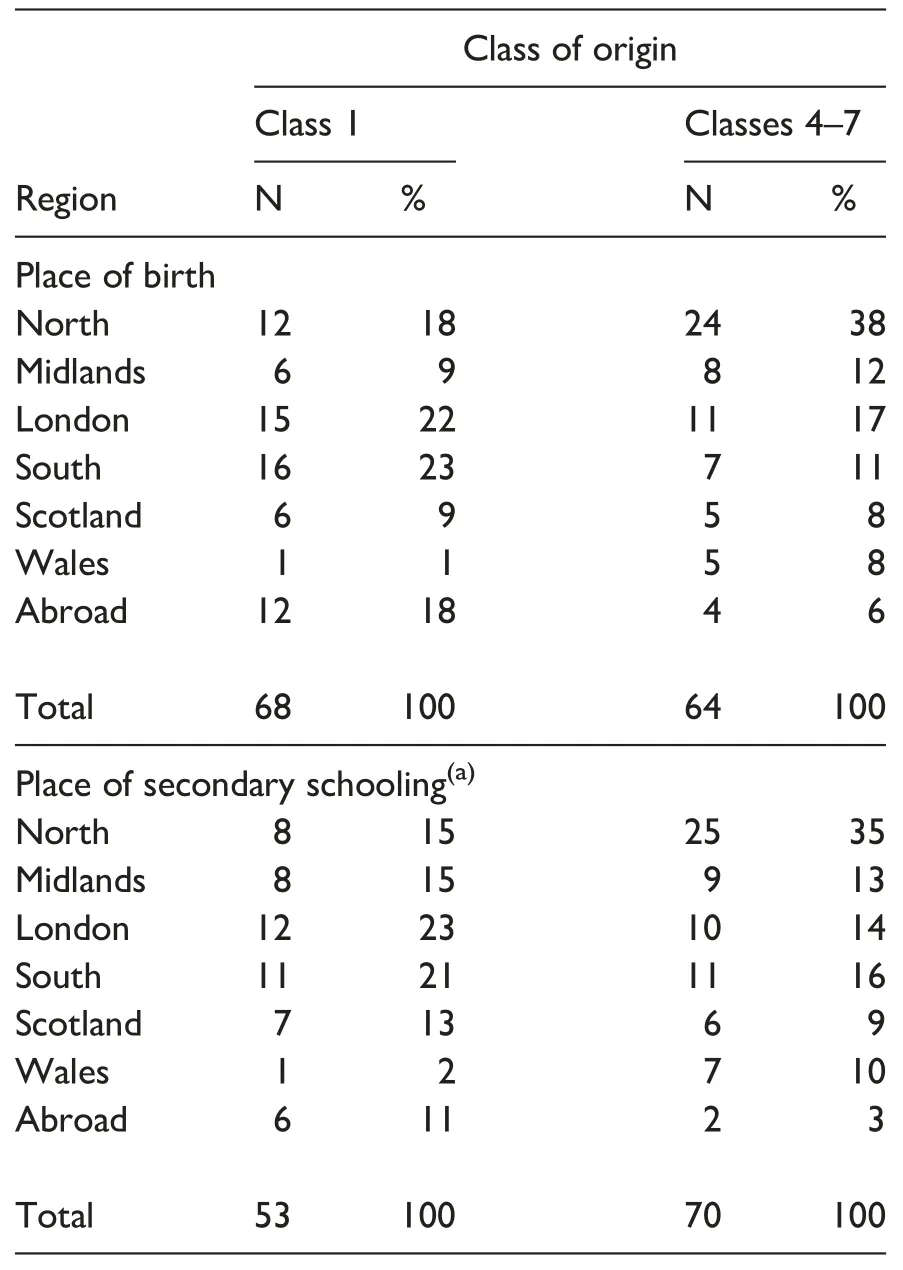

However,if we consider differences in geographical originsamongchemists in relation to their social origins,distinguishing between those of Class 1 and of Classes 4–7 origins,more interesting results emerge.We have been able to obtain information on place of birth for 68 of the 87 chemists of NS-SEC Class 1 origins and for 64 of the 82 chemists of Classes 4–7 origins.And we can further supplement this information by that on their place of secondary schooling in the case of 53 of the former and 70 of the latter (discounting instances where individuals were sent away to private boarding schools).However,in order to avoid unduly small numbers in cross-classifications,we have now to collapse the English regions as follows.North-East,North-West and Yorkshire and Humberside become the ‘North’,East Midlands,West Midlands and East become the ‘Midlands’,and South-East and South-West become the‘South’.

On this basis,we obtain the results shown in Table 1.It can be seen that,whether we consider place of birth or place of secondary schooling,chemists of relatively disadvantaged,Classes 4–7,origins are in fact clearly more likely to be northerners than those of Class 1 origins.Offsetting this,chemists of Class 1 origins are more likely than those of Classes 4–7 origins to have grown up in London and the South.7Once social origins are taken into account,the Northern chemist stereotype does then again find some echo.

Table 1.Distribution of chemists by class origins and place of birth and by class origins and place of secondary schooling.

The question can,moreover,be raised of whether it is merely physical,or rather economic,geography that is chiefly reflected in our results.It may further be noted from Table 1 that,while among chemists of Class 1 origins very few were born or had their secondary education in Wales,the proportion of those of Classes 4–7 origins who were of Welshorigins is larger.If,then,we are ready to think of chemists of less advantaged class origins as tending to come from regions that are,or at least were,characterised by extensive industry,extractive as well as manufacturing,a still sharper contrast can be made.Among chemists of Classes 4–7 origins,46% were born in the North or in Wales,and 45%had their secondary schooling in these regions,as against only 19% and 17%,respectively,of chemists of Class 1 origins.What is also of interest is that,if with the former group we go into somewhat more detail,we find that they grew up not only in the major cities of the North and Wales but also in the smaller coalmining,textiles and metalworking towns of these regions,such as South Shields,Hyde,Wigan,Todmorden,Pudsey,Neath and Llanelli.

We move on next to the information that we have been able to gather about how our elite chemists first became interested in and gained enthusiasm for the subject,leading on to their eventual study of chemistry at university.In the case of those of relatively disadvantaged class origins,various linkages with early years spent in industrial settings become apparent.

3.The entry into chemistry: The influence of families and schools

In this connection,we draw on the more detailed biographical information that,as earlier noted,we were able to obtain for 38 of our elite chemists who were of Class 1 origins and for 49 who were of Classes 4–7 origins.For deceased individuals,this material comes mainly from Royal SocietyMemoirsor other obituaries,so that we are not dealing directly with these chemists’own recollections and views but rather with these as reported by their memorialists or obituarists—who have usually consulted family members,colleagues and friends.We are,though,in some cases able to draw also on accounts of interviews,lectures or speeches made by the chemists themselves,available on the web,and for those of our chemists who are still living,it is material of this latter kind that is our main resource.8Almost all of the material we use is therefore in the public domain.However,in using it,we refer to individual chemists only by their index number in our data files and not by name,since we do on occasion make links with information deriving from our web questionnaire,respondents to which were assured of anonymity.

3.1 Families

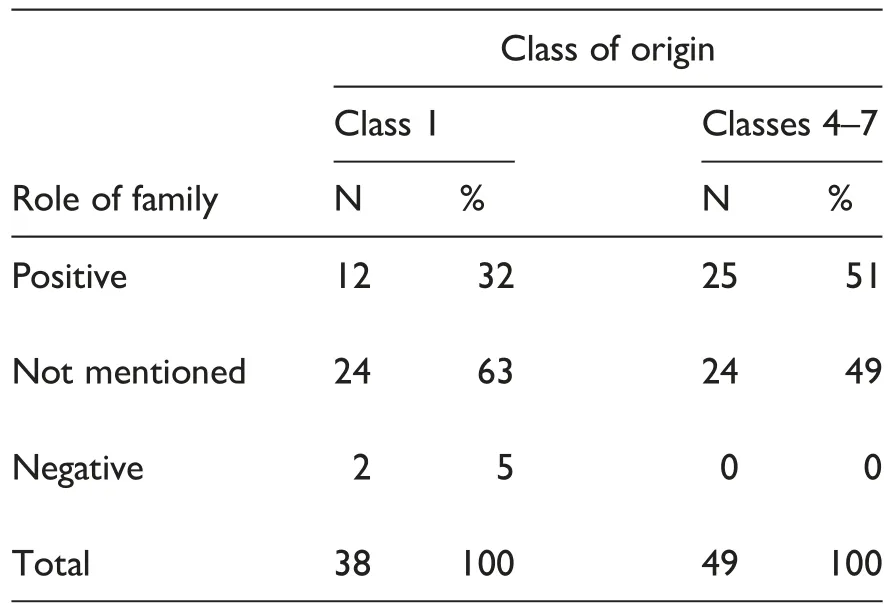

The family is an obviously important context within which individuals may develop interests that influence the subjects they choose to study in school and,in turn,the course that their future careers take.In Table 2,using the more detailed biographical data that we have referred to,we distinguish for elite chemists of Class 1 and of Classes 4–7 origins between those where a positive family influence on their careers as chemists is reported and those where no mention of family is made or a negative influence is reported.What is most notable is that family support for their careers is less apparent among chemists coming from Class 1 origins than among those coming from less advantaged Classes 4–7 origins.

Table 2.Role of family in influencing study of chemistry and choice of chemistry as a career by class origins.

Light can be thrown on these bare numbers by considering individual cases.With chemists of Class 1 origins,where the family did appear to be a source of their interest in chemistry,this largely arose as the result of their fathers being themselves chemists,being in some way involved with chemists or with the chemicals industry,or being natural scientists in some other field.The following eight cases of the 12 are illustrative.9

91,father a professor of chemistry,birth cohort 1900–09.

His father had a laboratory at home that from a very early age he was encouraged to use to carry out his own experiments.115,father an educationist,birth cohort 1910–19.

Her father had a close friend who was a chemist.He interested her in the subject and bought her a chemistry kit so she could do her own experiments.Her mother then supplemented this by buying chemicals from the local pharmacy.

813,father owner of a chemicals firm,birth cohort 1920–29.

He was born into a family long established in the chemicals industry.It was expected that he would follow in the family tradition,and he was encouraged to study chemistry at school and at university.

761,father a professor of chemistry,mother a research chemist,birth cohort 1920–29.

He was told by his father at an early age that he was to become a great scientist and was encouraged to concentrate on chemistry.He learnt a great deal of chemistry from his father and mother.

1172,father an industrial chemist,birth cohort 1930–39.

His father was the research manager at a large chemical plant,which he visited regularly as a child.He was encouraged to specialise in chemistry at school.

419,father an electronics engineer and inventor,birth cohort 1940–49.

My father told me when I was very young that I should aim to be a great scientist.I specialised in science at school and found chemistry particularly attractive because it needed less maths than physics,and I decided to study it at university.

436,father a professor of chemistry,birth cohort 1940–49.

I was introduced to science,and especially to chemistry,by my father.I grew up in a scientific world.As a schoolboy,I met many famous chemists.

192,father an academic chemist,birth cohort 1960–.My father encouraged me to take natural sciences,including chemistry,at the time when I had to decide which subjects to study in the sixth form at school.I then went on to study chemistry at university.

The two cases in which there was no family support for a career in chemistry were rather different.In one,the father wished his son to work in the family transport business rather than going on to university.In the other,the family was much involved in literature and the arts and had no interest in,and was rather dismissive of,science.

With chemists of Classes 4–7 origins,family support for the study of chemistry did not,as might be expected,come in entirely the same way as with chemists from Class 1 origins.But fathers’ or other family members’ occupations and their links with chemistry were often influential.

196,father a farm foreman,birth cohort 1900–09.

He came from a farming family in which there was some knowledge of the chemistry involved in farming through fertilisers and pesticides.In this way,he became interested in chemistry more generally from an early age.

199,father a smallholder,birth cohort 1910–19.

He had an uncle who was a chemical technician at a nearby steelworks,with whom he spent most of his school holidays.He was allowed into the laboratories,saw how experiments were done,and started doing his own experiments at home.

543,father a warehouse foreman,birth cohort 1920–29.

His grandfather had worked in an explosives factory and talked to him a lot about the chemistry involved.This greatly interested him,and he decided to concentrate on chemistry at school.

778,father an industrial painter,birth cohort 1920–29.

His father’s work gave him an interest in what was involved in the mixing of paints of different kinds and colours.He first learnt about chemistry as a subject from an uncle who worked in a chemicals factory.He visited him on most Saturday mornings and was allowed to watch experiments being carried out in the firm’s laboratory.

660,father a mechanic and garage owner,birth cohort 1920–29.

He helped his father in running his garage and became interested in how cars worked.He learnt some chemistry from scientific encyclopaedias that his father owned,and was able to use old car batteries in experiments that he made in electrolysis,and also as a source of sulphuric acid for other experiments.

130,brought up by an uncle,a semi-skilled worker in a chemical plant,birth cohort 1920–29.

His uncle,who was a shop steward and active in the labour movement,encouraged him to get a scientific education.After studying chemistry in the sixth form and working in the chemistry industry during the war and afterwards,he took a degree in chemistry through evening classes.

769,father a cabinetmaker,birth cohort 1920–29.

His father also worked part-time as a photographer,and his interest in chemistry originated through helping his father and learning about the processes involved in developing film.With his father’s support,he started doing experiments at home while still a schoolboy.

720,father a works carpenter,birth cohort 1930–39.

His father encouraged his early interest in science,especially chemistry,and impressed upon him,from experience in his own trade,the importance of accurate measurement and good design.This advice proved to be of great value to him in his later experimental work.

846,father a coalminer,birth cohort 1930–39.

He had an early interest in chemistry that his father encouraged,knowing its importance in mine production,as through shot-firing,and in safety through the detection and control of methane gas.His father brought him detonators and supplies of cordite from the mine,which he was then able to use in experiments at home.

Apart from there being such family occupational influences that helped to lead them into chemistry,elite chemists of Classes 4–7 origins would also appear to have often come from homes in which great importance was given to books and to the acquisition of knowledge,including of science.

431,father a village shopkeeper,birth cohort 1900–09.

Her father had a passion for books,including encyclopaedias and science books,which he bought from junk stalls.He encouraged her to read everything,and especially on science.

142,father a market gardener,birth cohort 1900–09.

His father was an autodidact with a large library including many books on science.He sought to teach his son basic science,including chemistry,from an early age.

150,father a mechanic in a bicycle factory,birth cohort 1900–09.

His father was an autodidact and owned many books,including on chemistry,which he encouraged his son to read.He also had a microscope and a telescope,which he taught his son to use.

999,father a small builder,birth cohort 1920–29.

His father was widely read and very interested in science.He gave his son an upstairs room that he could convert into a laboratory and bought chemicals from the local pharmacy for him to use in experiments.

616,father a cloth cutter in a textile factory,birth cohort 1920–29.

His father had read a good deal of science from magazines and helped him to set up his own laboratory in a garden shed where,as a schoolboy,he carried out experiments.He also emphasised,on the basis of his own work,the importance of accuracy in measurements.

1437,father a printer,birth cohort 1940–49.Like many printers,his father was widely read,including in popular science,and stressed the importance of education.He encouraged his son to try to qualify to study chemistry at university as it could mean secure employment.

What is brought to mind by the foregoing are accounts,such as that of Rose (2001),of the working-class intellectual life that flourished in industrial areas in Britain up to World War II,sustained by mechanics institutes and,later,by the Workers’ Educational Association—although in cases where the focus was on science rather than on literature or sociopolitical issues.In a wide range of primarily manual occupations,chemistry was involved at a practical level,and a concern to acquire a deeper knowledge of the subject could then arise,which might be further pursued and,in the case of the chemists in question,was so pursued in the filial if not in the parental generation.

In this connection,however,one other more general point has to be noted.Whether through the degree of scientific background that came from their own work or from their self-education,it isfathersor other male family members—grandfathers and uncles—rather than mothers,who would appear to have been the main sources of influence on the children who became eminent chemists.Mothers have often been regarded as of particular importance in encouraging children in their education,and especially in the case of children coming from less advantaged social backgrounds.But at least with the children here in question,the influence of mothers on their education and their careers would appear to have been very limited.References to such influence are in fact almost entirely confined to cases where the father had died early or was away from home for long periods,as at war or at sea.The extent to which the world of chemistry would appear subject to male dominance is thus in another way brought out.

3.2 Schools

Schools are a further obvious context within which young people may develop an interest in a particular field of study,as,say,because of particular emphases in schools’ curricula or through the influence of outstanding teachers.What part,then,did their schools play in the scientific careers of the elite chemists we consider,and how far do differences arise in relation to their class origins and to the type of school—private or state—that they attended?

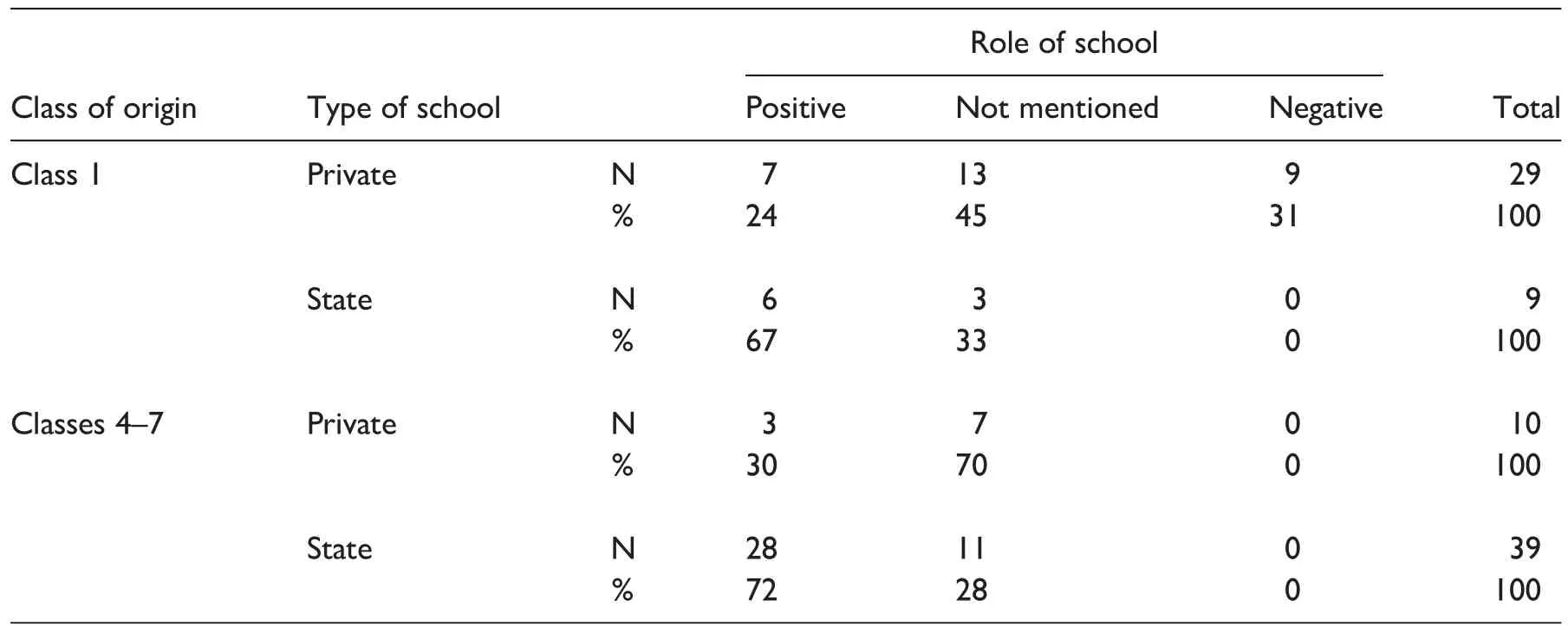

In Table 3,drawing on the more detailed biographical material that we have available,we provide some basic numerical information on how the chemists with whom we are concerned appeared to view their schooling.As with family,we distinguish between cases where,indirectly or directly,positive views were reported,those where we find no mention of schooling,and those where views were negative.

Table 3.Role of school in influencing study of chemistry and choice of chemistry as a career by class origins and type of school.

Although we are dealing with rather small numbers,Table 3 reveals some striking differences.With chemists of Class 1 origins,what we learn from the material to hand is that for those who were privately educated—the large majority—their experience of their schools would appear to have been very mixed.No mention of their schooling in relation to their future careers is the most common outcome,while a negative view is reported slightly more often than a positive one.It is in fact only in the case of this group of chemists that negative views about their schooling emerge.Among the minority of chemists of Class 1 origins who went to state schools,positive views are the most frequent.And similarly,among the large majority of chemists of Classes 4–7 origins who were state educated,positive views of their schooling in relation to their careers are predominant,while among the few who went to private schools(all but one through scholarships)no mention of their schooling is again the most common outcome.

Some indication of what lies behind these results can once more be gained from details taken from particular cases.We begin with the nine chemists of Class 1 origins whose experience of their private schools could not be regarded as favourable.

398,father a landed estate owner,birth cohort 1900–09.

He learnt nothing of value to his future career as a chemist from the teaching at the school he attended,only from the science books that he found in the library.He turned a room in his parents’house into a laboratory,in which he did experiments during vacations.

102,father a technical college headmaster,birth cohort 1900–09.

There was no chemistry teaching at his school.He learnt science mainly through teaching from his parents and left school for university to study chemistry at age 16.

117,father a chartered accountant,birth cohort 1900–09.He did not do well in science at his school and disliked the teaching.He was thought to be ‘only average’.He did not become interested in chemistry until taking a general sciences course at university.

86,father a GP,birth cohort 1910–19.

He learnt his chemistry mostly at home through reading the textbooks of an elder sister and from experiments that she did in the family potting shed.He learnt little at his school,where the standard of teaching was low,and he was always well ahead of his class.

433,father an inspector of education and mother a secondary school headmistress,birth cohort 1910–19.

There was no teaching of chemistry on the science side of his school,only of mathematics and physics.At university,he became interested,through mathematics,in theoretical chemistry.

772,father a dentist,birth cohort 1920–29.

At school he was put on the classics side and only allowed to make ‘the forbidden transition’ to such science teaching as was available through the intervention of a teacher who recognised his scientific abilities.He started learning chemistry seriously only at university.

916,father a GP,birth cohort 1930–39.

He did not do well in science at his school and left to go to a technical college in order to qualify for university admission.It was only at university that his interest in chemistry developed.

613,father a corn merchant,birth cohort 1940–49.

He was taught little chemistry at school and specialised in mathematics.He became involved in chemistry only at university through the application of mathematics in theoretical chemistry.

1361,father a financier,birth cohort 1960–.

I became interested in chemistry as a child but already through my experience of the teaching of chemistry at my school,which was not very encouraging,I became aware of the difficulties for women to make their way in this field.These observations may then be set in contrast with positive ones concerning their school experience in the case of chemists of Classes 4–7 origins who were state educated.

474,father a hill farmer and slate quarry worker,birth cohort 1900–09.

His interest in science and in particular in chemistry was aroused at his grammar school.The head gave him special lessons to help him gain university entry.

156,father a blacksmith,birth cohort 1910–19.

His secondary school had excellent chemistry teachers and also had regular visits from a chemistry lecturer from Manchester University.

441,father a worker in a clothing factory,birth cohort 1910–19.

His grammar school had a strong science tradition.Laboratories were kept open during vacations,and students were also encouraged to carry out chemistry experiments at home.

183,father a policeman,birth cohort 1910–19.

His secondary school was part of a technical college and so had excellent laboratories and good chemistry teachers.

776,father a textiles worker,birth cohort 1920–29.

His grammar school specialised in science.He was‘taken in hand’ by the chemistry master and prepared for university entrance to study chemistry.

570,father a railwayman,birth cohort 1930–39.

He attended a technical school where his interest in chemistry started.Inspired by the teachers there,he moved on to a related technical college where he took a London External degree in chemistry.

126,father a loom overlooker and a cotton weaver,birth cohort 1930–39.

I went to a grammar school that had produced two Nobel Prize winners and all science teaching was of a very high standard.

163,father a door-to-door salesman,birth cohort 1950–59.

I left school at 16 to work as a laboratory technician with a large pharmaceuticals firm.I was ‘talent spotted’ and encouraged to take a degree in chemistry through evening classes at a technical college.The teaching was excellent and made me want to become a research chemist.

936,father a case-maker and packer,birth cohort 1950–59.

I was inspired by the chemistry teachers at my grammar school—Isaac Newton’s school!

1364,father a factory parts inspector,birth cohort 1960–.

I found chemistry difficult when I first went to secondary school,but my teacher was excellent and it wasn’t long before I was borrowing chemicals from him to do experiments in my bedroom.I was hooked on bright colours,noxious smells and loud explosions.

What is reflected in the foregoing are in fact certain well-recognised features of the history of secondary education at least in England and Wales—Scotland being perhaps a somewhat different case.In the later nineteenth century,Francis Galton(1874)criticised the‘public’(i.e.,private)schools of his day for their concentration on classics and their neglect of,and often hostility towards,science.They constituted,he claimed,a ‘gigantic monopoly’ of the clergy that was yielding only very slowly to the demands of modern society.And indeed science teaching at private schools would appear to have remained,with only a small number of exceptions,10quite limited and of indifferent quality until after World War II;and even then,while teaching in mathematics and to some extent in physics did become more common,teaching in chemistry was particularly deficient because few schools had adequate laboratories.Only from the 1960s did things begin to change.‘Modern sides’,which had been introduced as an alternative to classics,increasingly covered the sciences as well as modern languages and history.The number of science teachers increased,and,through the Industrial Fund for the Advancement of the Teaching of Science,business firms provided millions of pounds to private schools to build new science laboratories (Turner,2015).It may then be that the very mixed experience of private schooling among the elite chemists we have studied will be less evident among their successors.Nonetheless,it would appear—though the numbers we can draw on are not large—still to persist through into the later birth cohorts we cover.One possibility is that,despite the improved provision for the teaching of chemistry in private schools,its status as a subject in these schools has tended to remain relatively low,and that this is reflected in the often ambivalent attitudes towards their schools of the especially talented pupils in chemistry who were destined for elite status.

In state secondary schools,the situation was historically clearly different.After reforms in the early twentieth century,the classics no longer dominated curricula,and science teaching,including practical work in laboratories,steadily increased in importance,becoming not a matter of choice for schools but a requirement under state regulation.In some grammar schools,the reverse situation to that found in many private schools in fact existed:there was no sixth-form teaching in arts subjects,only in the sciences.11By the inter-war years,science teaching in grammar schools,and also in various forms of technical schools and colleges in which chemistry flourished,12was generally accepted as being superior to that in private schools,and this continued to be widely the case into the postwar years(Turner,2015).

Over the period we cover,children who went to state schools could then be seen as having something of an edge over children attending private schools so far as making progress in chemistry was concerned.Among those of our elite chemists who were privately educated,their schooling would often appear to have done little to nurture an early interest in chemistry,whether deriving from their families or otherwise,or to encourage its pursuit to university level.In contrast,among those who went to state schools,and especially from relatively disadvantaged social origins,their schools often played a major role either in first creating an interest in chemistry or in developing a pre-existing interest so that studying chemistry at university became a possibility.And as regards entry into the scientific elite,the route through chemistry could thus be regarded as offering somewhat more equal chances of success than did those through other fields,in relation to individuals’ type of secondary schooling and their social class backgrounds.13

4.Conclusions

We have started from the finding that within the British scientific elite,defined for the modern period as Fellows of the Royal Society born since 1900,chemists appear distinctive in coming more often than Fellows working in other fields from relatively disadvantaged social origins and in having more often attended state rather than private secondary schools.In thinking of possible explanations for this finding,we called to mind the student stereotype of ‘the Northern chemist’and wondered if this might give some indications of how it came about that those chemists who succeeded in entering the scientific elite—a small minority—should still tend to differ from other elite members in the ways in question.

‘The Northern chemist’was taken to be male,and we do in fact further find that,while the scientific elite is in general male dominated,women are yet more poorly represented among chemists than among Fellows in most of the other subject areas that the Royal Society defines.

As regards geographical origins,chemists taken overall do not appear to be especially northern,as judged by either place of birth or of secondary schooling.But if we consider those chemists who are of more disadvantaged origins (i.e.,NS-SEC Classes 4–7) we do see that they are more likely to be northerners by birth and/or schooling than their counterparts of Class 1 origins,who come more often from London or the South.And this difference is widened if we also take into account origins in Wales,as another region in addition to the North in which extractive and manufacturing industry has been concentrated.

In turning then to the influences that led to entry into chemistry,we find,from those cases for which we have the most detailed biographical information,that further clear differences arise among elite chemists in relation to their class origins.

Family influence appears to have been generally less important for chemists of Class 1 origins than for those of Classes 4–7 origins,and to be largely confined to cases where fathers were chemists,had connections with the chemicals industry or were scientists in other fields.With chemists of Classes 4–7 origins,the influence of fathers or of other—male—family members could again arise through these men being workers in the chemicals industry,but also through their having other mainly manual occupations in which some degree of chemistry at a practical level was involved.And of further importance was fathers’interest in science,including chemistry,as reflected in their acquisition of scientific books,instruments and materials and the encouragement that they gave to their children—mainly sons—to share in their interests and to gain some knowledge of chemistry outside of school.

As regards the influence of schools themselves,differences are further apparent between chemists of more and less advantaged social origins.Chemists of Class 1 origins mostly went to private schools,and those who did so appear to have been as likely to express negative as positive views of the experience,so far as their future careers in chemistry were concerned.In contrast,the majority of chemists of Classes 4–7 origins attended state schools and were very largely positive about the education in chemistry that they received,as also were the minority of those of Class 1 origins who went to state schools.These findings,we have noted,are much as might be expected,given what is known about differences in standards in the teaching of chemistry in private and state schools up to at least the 1960s.

How then,in the end,would we wish to account for the unexpected finding on the social distinctiveness of chemists within the scientific elite from which we began? In the light of what we have learnt from the data we have available,the explanation for this finding that we would suggest is on the following lines—and it is one that would in various ways be open to further empirical evaluation.

Over the period we cover,young people,predominantly male,coming from families relatively disadvantaged in class terms,and often growing up in the North or in Wales,were led to study chemistry at school and then at university in significantly larger numbers,and more successfully,than their counterparts who turned to other sciences.Children from such families were more likely to gain an interest in,and some initial knowledge of,chemistry,rather than of other sciences,such as physics or biology,as a result of their fathers’ or of other male family members’ work in the chemicals industry itself or in a range of other largely manual occupations that required in some degree the practical application of chemistry.Moreover,in so far as these children did develop scientific interests,whether in this way or simply through encouragement from fathers following in a working-class tradition of self-improvement,it was in chemistry rather than in other sciences that their education,mainly in state secondary schools,gave them their greatest comparative advantage;that is,both over those studying other sciences and over those seeking to study chemistry in private schools.In this way,a larger pool was created in chemistry than in other scientific fields of people working in universities and research centres who were of relatively disadvantaged class origins and state educated.And this difference was then maintained through into the social composition of the very small number of those chemists who eventually,after all the processes of selection involved,gained entry into the scientific elite.

Finally,though,to return to the Northern chemist stereotype,we might note that in one respect this could be thought quite misleading:that is,in suggesting a somewhat socially limited and withdrawn individual.The more detailed biographical information that we have of chemists of Classes 4–7 origins gives the impression that they did in fact tend to have high levels of social participation,and especially through playing,and in later life administering or watching,sports.It is,though,further notable that it was soccer and cricket,the dominant sports in the northern industrial areas from which many came,that were by far the most frequently referred to—with one man having played soccer professionally and another being a double Oxford blue in soccer and cricket.Rugby was mentioned by only two men,both from Wales,while sports such as tennis or squash were only rarely mentioned,and golf not at all.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research,authorship,and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research,authorship and/or publication of this article: This work was funded by the McGrath Trust.

Notes

1.Excluding Honorary and Royal Fellows,Foreign Members,all deceased Fellows whose last employment prior to retirement was not in the UK,and all living Fellows whose most recent employment was not in the UK or who would appear to have spent substantially more of their research careers outside of rather than within the UK.

2.We here distinguish NS-SEC Class 5,while in our paper previously cited it was collapsed with NS-SEC Class 4 of‘intermediate’(i.e.mainly clerical and lower administrative) occupations.

3.Direct grant grammar schools are also counted as state schools,but they were attended by less than 5% of Fellows in any subject area.We also distinguish a category of ‘other’ secondary schools,mainly religious ones,which were attended by around 8% of all Fellows.

4.The subject areas within which Fellows came into the most marked contrast with chemists as regards both their class origins and schooling were ones in those biological sciences with medical and health connections:developmental biology and genetics,immunology,microbiology;anatomy,physiology,neuroscience;organismal biology,evolutionary and ecological science;and health and human sciences.However,while Fellows in these fields become somewhat less distinctive in their class origins and schooling across birth cohorts,this was not the case with chemists.See further Bukodi et al.(2022).

5.Across the biological sciences,women account for over 10% of all Fellows.Of the 12 women chemists for whom we have relevant information,three were of Class 1 origins and three of Classes 4–7 origins.None was born in the North.

6.We omit Northern Ireland,since none of the chemists included in our study was born there.

7.This particular association between geographical and social origins is not one generally found among our elite scientists,although,rather oddly,there is some suggestion of it among those in the biological sciences previously referred to who overall contrast most sharply with the chemists in their social origins and schooling.

8.Because memoirs and obituaries are more generally available than reports of interviews etc.,there is some bias among the chemists we consider towards those in earlier birth cohorts.But,as earlier mentioned(note 4),there is no tendency for the distinctiveness of chemists as regards either their class origins or schooling to diminish across cohorts.It should in this connection also be noted that the average age of election to Fellowships of the Royal Society has been steadily increasing and by 2019 had reached 58(Royal Society,2019).

9.Both third-person statements coming from documentary sources and first-person statements are lightly paraphrased in the interests of conciseness,and some minor details have been changed in order to reduce the possibility of personal identification.Also for this reason,we give individuals’ birth cohorts rather than actual years of birth.

10.The most notable exceptions were the three leading London private schools—the City of London School,St Paul’s School and Westminster School—and Winchester.Of the seven chemists of Class 1 origins for whom positive views of their school experience are reported,one went to the City of London School and three to Winchester.

11.This was the case at the Leicester grammar school attended in the 1920s by CP Snow—later famous for initiating‘the two cultures’debate.In seeking university entry,he had to turn to science,despite having had his academic interests first stimulated by a history teacher(Ortolano,2009).

12.Technical schools and colleges were of particular importance in the development of chemistry as an academic subject from the later 19th century onwards.Of the 16 eminent chemists whose biographies appear in the collection of Findlay and Mills(1947),previously referred to,only two went to‘public schools’,and only one to Cambridge and one to Oxford.Two others went to Scottish schools and universities.The remainder all had at least some substantial part of their secondary and tertiary education in technical schools and colleges,mostly in London—notably,the Central Foundation School,Finsbury Technical College,South Kensington Technical College and the Royal College of Chemistry.

13.Members of the scientific elite who came from less advantaged class origins and who went to state schools were in general less likely than those coming from more advantaged origins and who were privately schooled to have been at Oxford and Cambridge,either as undergraduates or postgraduates.However,we find no evidence of this difference being more marked in the case of chemists than of those working in other fields.

- 科学文化(英文)的其它文章

- Creating common ground: The 17th international conference of the Public Communication of Science and Technology Network

- The evolution and predicament of modern social technicalization

- Traditional farm tools observed from an ecological and health perspective

- Feng shui and the scientific testing of chi claims

- Understandings and misunderstandings of gua sha:A discussion from the perspective of scientific multiculturalism

- On the diversity of scientific culture and the tradition of postpartum confinement in China