Literature, History, Regulation, Craftsmanship, and Aesthetics

Chen Congzhou

Chen Congzhou is a renowned scholar of ancient architecture and garden art. He is considered a pioneer and founder of modern Chinese garden studies. He used to be a professor and doctoral supervisor at Tongji University.

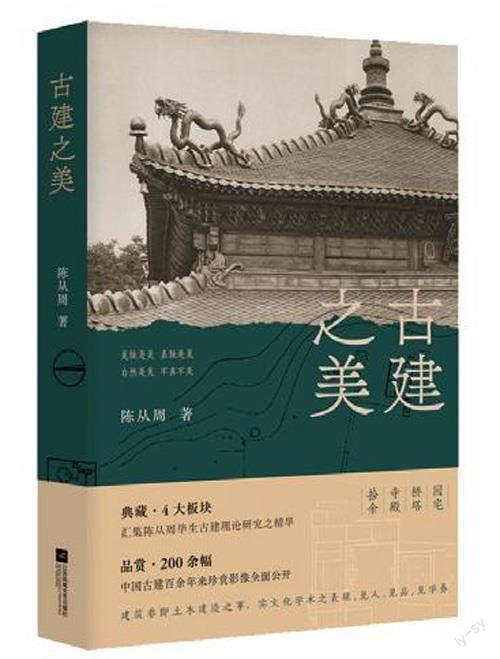

This book compiles the authors lifelong research, exploration, and evaluation of ancient architecture. The articles can be categorized into four sections: “Gardens and Residences,” “Bridges and Pagodas,” “Temples and Palaces,” and “Miscellaneous items.” The book not only covers the authors detailed examination of numerous representative ancient buildings in China but also delves into various aspects of Chinese architectural craftsmanship, techniques, features, research, and preservation.

The Beauty of Ancient Architecture

Chen Congzhou

Jiangsu Phoenix Literature and Art Publishing

April 2023

98.00 (CNY)

The publication of Chen Congzhous collection of essays on ancient architecture, The Beauty of Ancient Architecture, brings great joy to us, his former students, evoking memories of the times when we listened to lectures, read books, conducted surveys, and sketched during field trips. Chen Congzhous research on ancient Chinese architecture is comprehensive, bridging the past and present and encompassing both traditional Chinese approaches to learning and contemporary scientific research methods. Upon reading the book, four outstanding stylistic features emerge.

Firstly, Chen emphasizes historical and cultural context. Proficient in historical sources, he believes that exploring the beauty of ancient architecture must commence with historical literature. This entails consulting related local gazetteers, reading historical records from different eras, examining inscriptions on tablets and steles, and inquiring about legends. His perspectives span across various regions such as Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Shanghai, Guangdong, Shanxi, Shandong, Beijing, and Henan. In his essays, he succinctly presents the evolution, rise, and decline of relevant ancient architecture and its historical figures in just a few hundred words. For example, in the article “The Yuan Dynasty Main Hall of Yanfu Temple in Wuyi County, Zhejiang,” he provides an insightful analysis of the buildings inscriptions and history, leaving a remarkable impression. Moreover, people and events associated with ancient architecture are also subjects of his research and concern. His article “Zhu Qiyao and the China Architectural Society” offers distinctive perspectives and historical references.

Secondly, he studies architectural regulations and patterns. Chen Congzhous research on ancient architecture extends beyond the structures themselves to encompass historical systems and the influence of customs. He once asked us, “Why is the peony called the ‘King of Flowers?” We were unable to answer. He explained that a peony has one main stem with three branches, each branch bearing three leaves, symbolizing the three highest officials and nine ministers, reflecting the ideal structure of ancient governance. Architecture operates similarly, as it is a form of expressing social relationships. Chen urged us to explore the “spirits, modalities, and carriages” of architecture. Thus, in articles such as “The Architecture of the Prince Gong Mansion,” he not only examines the relationship between ancient Chinese architectural patterns and regulations but also delves into the social evolution signified by these patterns.

Thirdly, he considers craftsmanship and techniques. Proficient in painting, Chen Congzhous meticulous observation skills extend to architectural details, proportions, materials, and craftsmanship. His thought-provoking viewpoints on non-literary and non-regulatory aspects, as well as craftsmanship and aesthetics, are evident in articles like “Yao Chengzu and the Original Principles of Construction Law.” I still recall how he fundraised to reproduce the “Kuang Ji Tu” and “Yan Ji Tu” illustrations, which can still be found today in old online book markets. These meticulous efforts stand out in the field of ancient architectural research.

Lastly, he pursues understanding through observation. “The moon shines bright among the sparse stars, and the magpies are flying to the south. They circle the tree thrice, not sure on which branch to perch.” This excerpt from the poem “A Short Song” was adapted by Chen Congzhou into a four-line motto for his students when surveying ancient architecture: “Sharp eyes, keen minds; find north and south; circle the building thrice, and align with the axis.” This embodies the contemporary architectural methods applied during field surveys. Approach the task with reverence, observe carefully, ascertain orientation within the terrain, describe the overall relationships between buildings, adjacent structures, streets, and rivers, and visualize the invisible “axis.” While cherishing traditional culture, Chen actively employs modern scientific and technological methods, refusing to remain conservative. For example, he is well-versed in the camera models used by German scholars Ernst Boerschmann and Liang Sicheng for studying ancient Chinese architecture. He also shares insights on photographing interior shots of ancient buildings: using black-and-white film, a tripod, apertures of f/16 to f/22, and slow exposure speeds of 10 minutes, resulting in photographs clearer than those seen with the naked eye. He even showed us glass negatives of ancient architecture and the old and new cameras he used. In the article “The Baodai Bridge in Suzhou,” we can witness his qualitative and quantitative analysis of the geometric shape and material composition of the ancient bridge.

I had limited opportunities to accompany Mr. Chen Congzhou on field surveys of ancient architecture outside our hometown, as I became his student when he was already in his seventies. But I was fortunate enough to assist him in measuring and sketching the Daibo Temple in Taian, Shandong. I also had the honor to join senior fellow student Wang Lumin on research trips to Luoyang, Xinmi, Sanmenxia, and Fenglingdu and visits to Qufu, Zoucheng, Yanzhou, and Guangrao with Wang Lumin and Yong Zhenhua, totaling over fifty destinations. Thinking back to those journeys and facing “The Beauty of Ancient Architecture,” I can better appreciate Chen Congzhous research style and instructional methods regarding ancient architecture. I feel grateful, reflective, and moved. The beauty of ancient Chinese architecture lies in its overall layout and cultural context, in both established regulations and adaptability, in craftsmanship and structural form, as well as in the pursuit of understanding and the continuity of tradition. To this day, Chen Congzhous viewpoints and methodologies in ancient architectural research continue to hold significant value for readers seeking to understand architectural cultural traditions.

- 中国新书(英文版)的其它文章

- Internet Is Not a Good Thinking Tool

- Listening to One’s Inner Voice: Turning Feelings into Actions

- Urban Skylines

- Translation and Mutual Learning Among Civilizations

- The Significance of Preserving Craftsmanship: Reflecting on “Ingenious Craftsmanship” After Visiting Over 100 Artisans

- Traditional Folk Medicine and Pharmacology Series of the Ethnic Minorities in Yunnan Province -- The Yi Medicine and Pharmacology