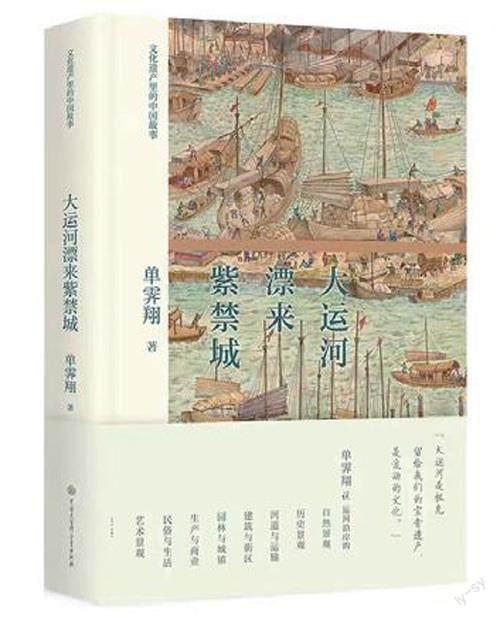

The Flowing Bloodline of the Nation

From the Grand Canal to the Forbidden City

Shan Jixiang

Encyclopedia of China Publishing House

October 2022

68.00 (CNY)

Shan Jixiang

Shan Jixiang holds a doctorate in Engineering and is a research librarian, senior architect, and registered urban planner. He has served as the director of the Beijing Municipal Planning Commission, the National Cultural Heritage Administration, and the Palace Museum. He is currently a distinguished researcher at China Central Institute for Culture and History, president of China Cultural Relics Academy, and director of the Academic Committee of the Palace Museum.

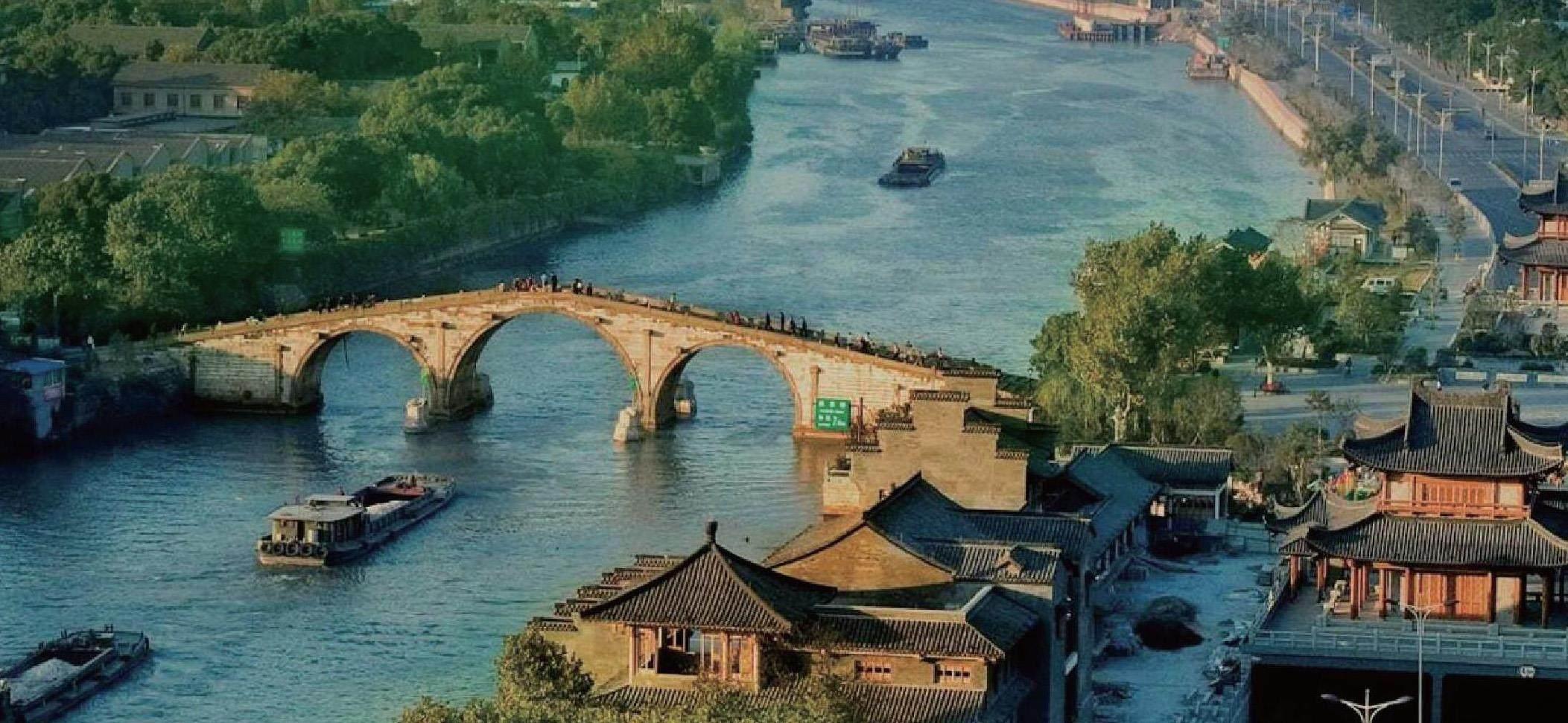

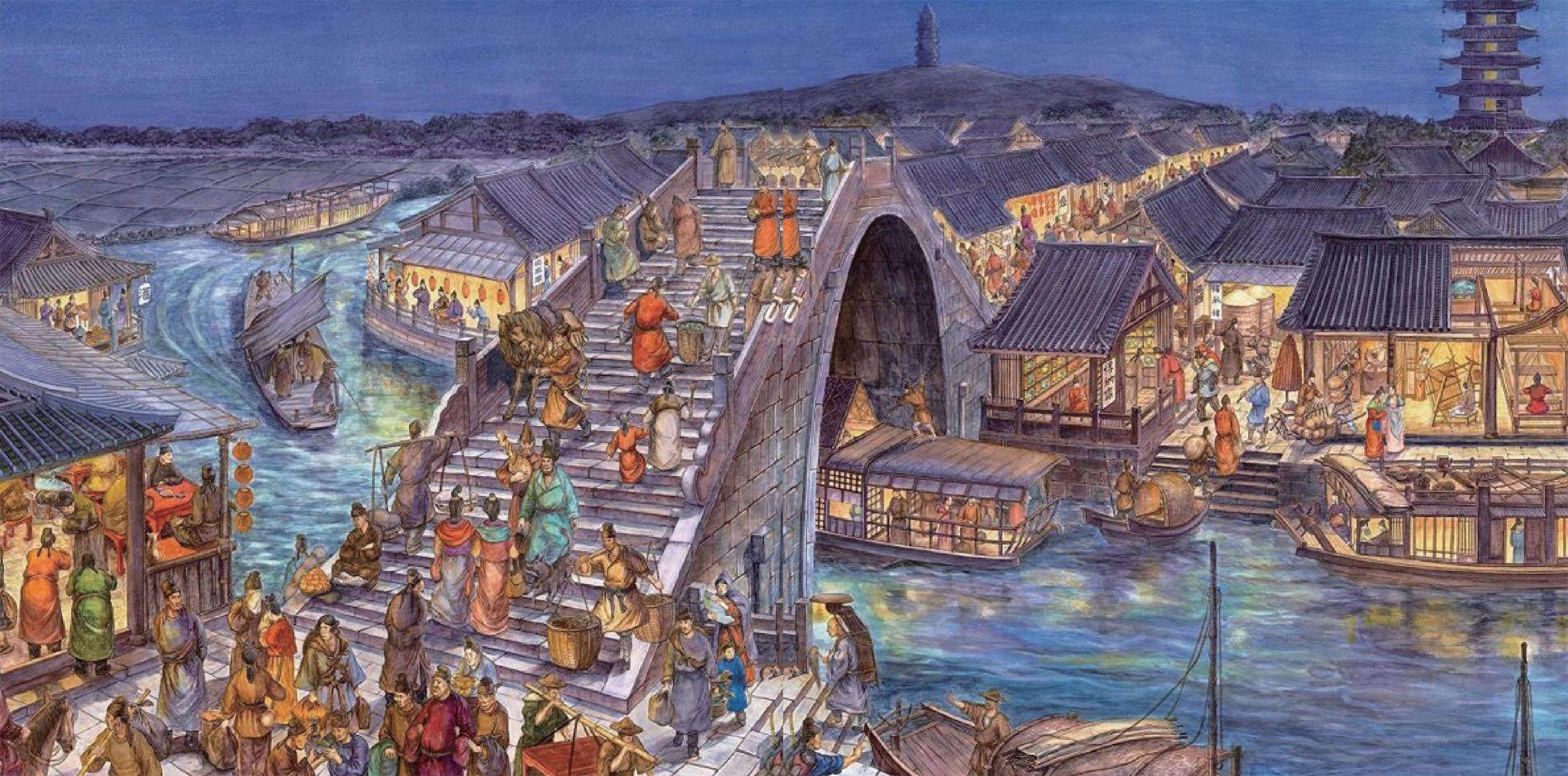

The Grand Canal in China consists of three parts: the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal, the Sui and Tang Grand Canal, and the East Zhejiang Canal. With a total length of over 3,000 kilometers, it has been excavated for over 2,500 years. It is the longest artificial canal in the world and the earliest artificial canal to be excavated. As a monumental creation by both humans and nature, the Grand Canal passes through more than 30 cities. It forms a major hydraulic artery connecting the Haihe River, Yellow River, Huai River, Yangtze River, and Qiantang River, playing a significant historical role in national unity, as well as economic and cultural exchange in ancient China, serving purposes like transporting grain from the south to the north, facilitating commerce and travel, distributing military supplies, and irrigation.

The Grand Canal links the core regions of ancient Chinese culture and civilization, connecting significant cultural areas such as the Xia culture, Shang culture, Chu culture, Yan culture, and Qi-Lu culture. It is a region with a concentration of ancient human settlements and cultural relics. Thus, the Grand Canal is not merely a river; it is a cultural corridor that encompasses transportation, water management, geography, history, ecology, and various other aspects.

In the 38th session of the UNESCO World Heritage Committee held in Doha, Qatar, on June 22, 2014, the Chinese Grand Canal project was listed in the World Heritage List. The success of the Grand Canals application for World Heritage status has played a crucial role in the protection of its cultural heritage.

Speaking of cultural heritage protection, I often recall an encounter with academician Yuan Longping. In 2009, he wrote a letter to the leadership, proposing that the rice paddies where he had worked on hybrid rice for 37 years be designated a national key cultural relic protection unit. At that time, I was hesitant. Ancient relics, tombs, historic buildings, and the Great Wall were commonly regarded as cultural relic protection units, but could a rice paddy be included in such a category? With this question in mind, I visited the Anjiang Agricultural School in Anjiang Town, Hongjiang City, Hunan Province. This place is in western Hunan, quite far away, and you have to travel even further after crossing Hongjiang. Eventually, I saw with my own eyes this hybrid rice field and some of the gear, equipment, and buildings where they worked, which were all very well preserved. More touching is that I went to see the room where academician Yuan Longping used to live. The Academician had made significant achievements in that very modest room, pondering future issues related to human survival on an ordinary wooden bed. Afterward, we wrote a report recommending the inclusion of this rice paddy in the national key cultural relic protection unit list, and it was specially approved. A year later, we returned to the Anjiang Agricultural School, where I had the honor of unveiling the memorial park with academician Yuan Longping. During my speech at the ceremony, I emphasized the visible contributions academician Yuan Longping had made to humanity and the Chinese nation. He solved our food problem. In the past, a harvest of four to five hundred jin (a Chinese measure equal to 500 grams) per mu (a Chinese area unit equal to 666.7 square meters) was already considered high. Today, weve exceeded one thousand jin. Food is the paramount necessity of the people! However, a philosopher once said that when people are hungry, they have only one worry: when they are full, they will have countless concerns. In other words, while academician Yuan Longping could solve the problem of human survival, he couldnt resolve all aspects of life. What can address complex life issues? I believe its culture. The successful inclusion of the hybrid rice paddy in the protection project provided an important revelation: We should not only protect “static” cultural relics but also focus on “living” cultural heritage.

Although the Grand Canal still maintains its vital transportation function and remains a significant part of socio-economic life in the Jiangnan region, from a broader perspective, its most important significance lies in its cultural value. This artificial river that traverses the heartland of China, nurtures both sides of its banks, serving as a spiritual homeland for millions of people.

If the Great Wall is the strong backbone of the Chinese nation, then the Grand Canal is the flowing bloodline of our people. On either side of the Chinese character “人” (people), there is the ancient Silk Road on land to the west and the Maritime Silk Road to the east, resembling a ribbon fluttering around the waist. This strong backbone, flowing bloodstream, and open exchange embody the history of progress, development, communication, and dialogue of the Chinese nations civilization.

Speaking for myself, the first time I proposed the protection of the Grand Canal at the National Committee of the CPPCC was in 2003, when I was serving as the director of the National Cultural Heritage Administration. Comparing it to when I first started paying attention to and getting involved in the application for Grand Canal heritage status, the publics understanding of the Grand Canals cultural heritage has undergone a profound change. Many cities along the Grand Canal have treated its heritage as precious cultural resources, engaging in research, protection, and utilization. The cities on both sides of the canal, with their vibrant economies and rich cultural foundations, constitute a valuable urban community for the Chinese nation. Personally, I am confident about the future of the Grand Canals cultural heritage. At the same time, I have consistently adhered to three goals for cultural heritage protection: to ensure the dignity of the cultural heritage we protect, to use cultural heritage to promote economic and social development, and to make the benefits of protection accessible to the general public, especially the local residents.

I am delighted to share the story of the Grand Canal with more readers once again and look forward to more people, especially the younger generation, casting their gaze upon the Grand Canal. I hope that more and more discerning individuals will engage in research, protection, and utilization of the Grand Canal.

- 中国新书(英文版)的其它文章

- Internet Is Not a Good Thinking Tool

- Listening to One’s Inner Voice: Turning Feelings into Actions

- Urban Skylines

- Translation and Mutual Learning Among Civilizations

- The Significance of Preserving Craftsmanship: Reflecting on “Ingenious Craftsmanship” After Visiting Over 100 Artisans

- Traditional Folk Medicine and Pharmacology Series of the Ethnic Minorities in Yunnan Province -- The Yi Medicine and Pharmacology