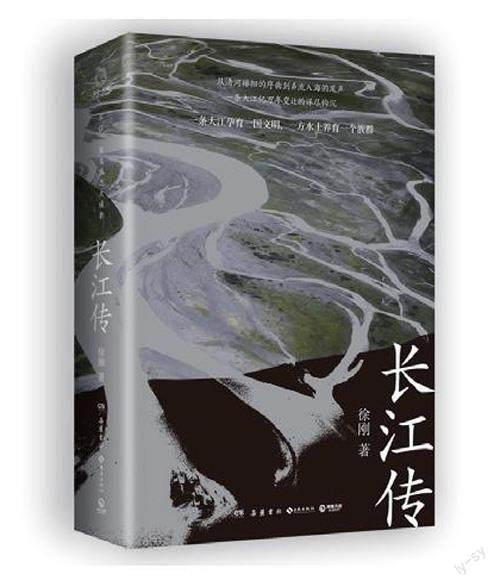

A Devout Journey

A Biography of the Yangtze River

Xu Gang

Yuelu Publishing House

January 2023

98.00 (CNY)

Xu Gang

Xu Gang is a member of China Writers Association, a council member of the China Environmental Literature Association, and an honorary environmental ambassador of Chinas State Environmental Protection Administration (SEPA). He previously served as an editor in the Literary Department of Peoples Daily, deputy director of the Editorial Department of Chinese Writers, deputy editor-in-chief and deputy editorial director of Modern People Daily. His works have been awarded the Chinese Book Award, the first Xu Chi Reportage Literature Award, and the first China Environmental Literature Award.

The Tuotuo River is now the legitimate source of the Yangtze River, known as “Mar Qu” in Tibetan, meaning “Red River,” and “Tokto Nai Ulan Moron” in Mongolian, meaning “Calm River.”

Geladaindong, meaning “Tall, Pointed Mountain Peaks” in Tibetan, stands at an elevation of 6,621 meters. In an area spanning 50 kilometers north to south and 15--20 kilometers east to west, there are over 40 snow-capped peaks at altitudes above 6,000 meters. Ice and snow cover an area of nearly 600 square kilometers, which hosts about 105 modern glaciers.

As the author narrates the general situation of the Yangtze Rivers origin, the Tibetan and Mongolian names of these rivers and peaks have already told us who the earliest discoverers were.

They didnt leave their names behind, but it is certain that they were wanderers seeking a celestial realm or Mongol or Tibetan herders watching over this wilderness.

Perhaps, the true discoverers never thought of their findings as remarkable. They simply felt that here, the sky was bluer and the water clearer, and the ice and snow under the sunlight were a dazzling temptation, a temptation that reached deep into the soul, not to possess, but to let go.

The seemingly tranquil glaciers are not calm at all. Under the influence of gravity and external forces like climate, even these immense glaciers are in motion, or one could say that the Yangtze River, nurtured by glacier meltwater, carries a propensity for movement. Before flowing outward, its already flowing within. Of course, the movement of glaciers is subtle, sliding downward at a rate of several to dozens of meters per year. Below the snow line, where temperatures rise, the glaciers lower edge begins to melt, forming a so-called “glacier tongue.” Glacier movement leads to fractures, and with the cycle of melting during the day and freezing at night, a marvelous world of ice towers emerges on these extended glacier tongues. The ice tower forest of the Yangtze Rivers source area showcases a truly magnificent creation, a divine creation of nature. Everything is casual yet meticulously crafted. It resembles both ancient pagodas and modern colossal structures. Between the ice towers, there are glacial lakes. Viewing the reflections of the towers in the lakes feels like an otherworldly experience. Among the ice tower forest, there are also ice needles, ice buds, ice mushrooms, ice stalactites, ice pavilions, ice corridors, and ice bridges. All these names are human-given, annotations left behind for this world of ice and snow. In reality, they are everything and nothing at the same time. For glaciers, falling is their mission. They accommodate their fall, melting, and freezing in sync with the environment. They are about to infuse this spirit of falling into the meltwater, becoming the spirit of the Yangtze River. The splendor of the ice tower forest is a record of the myriad changes in this falling process, a display of the masterful craftsmanship of nature.

People can certainly imagine.

When immersed in the crystal-clear ice and snow of the Yangtze Rivers source, if our imagination loses its clarity, humanity is truly beyond saving.

The creation of ice and snow is the creation of water. After the initial trickle flows out, the Yangtze River water is ready to nurture and give birth to all things with a spirit of falling. All the wonders of the ice tower forest can be found in the human world: the forested cliffs by the river, houses by the shore, flowing bridges, continuous lakes, pavilions, grand chants of the Sichuan riverside work songs, the bright gaze of the maiden by the Jialing River, and the snowy white of cotton and rice.

All of this can be called the homeland scenery nourished and connected as a whole by the flowing water of the Yangtze River.

The changes in the name of the Yangtze River and its various appellations are a complex interpretation of the rivers length and the diverse landscapes it traverses.

The Yangtze River was called “Jiang” (江) in ancient times, and just as “He” (河) referred to the Yellow River, in ancient times, “Jiang” was a special term referring specifically to the Yangtze River. The earliest discovered text using the term “Jiang” can be found in the Book of Songs. During the Han and Wei periods, when the intellectual climate was vibrant, the term “Jiang” seemed insufficient. People began to refer to it as “Da Jiang,” meaning “the Great River.” From then on, the term “Da Jiang” gained wide acceptance. The addition of “Da,” meaning big or great in Chinese, was apt and evocative. It appeared in numerous enduring poems, such as Su Dongpos “Nian Nu Jiao-- Memories of the Past at Red Cliff,” which begins with the lines: “The Great River eastward flows, with its waves are gone all those gallant heroes of bygone years.”

As understanding of the geography of the Yangtze River deepened over time, ancient people realized that the terms “Jiang” or “Da Jiang” couldnt fully express its vast and enduring nature. Therefore, a name that has been used to this day and is more universally recognized emerged: “Chang Jiang” (長江), meaning “Long River,” emphasizing its length.

The term “Chang Jiang” first appeared towards the end of the Eastern Han Dynasty. In the Records of the Three Kingdoms -- Biography of Zhou Yu, it is mentioned that Sun Quan discussed military matters with his subordinates, believing that they could resist Cao Cao by leveraging the strategic advantage of the treacherous waters of the “Chang Jiang.” The biographies of Lu Su and Lv Meng in the same book also contain references to the “Chang Jiang.” Based on this, and in the absence of new historical evidence, it can be inferred that the name “Chang Jiang” was already in use during the latter years of the Eastern Han Dynasty and the beginning of the Three Kingdoms Period, and the name was given possibly even earlier. After the Jin Dynasty, the term “Chang Jiang” gradually gained popularity. By the Tang Dynasty, the term had seemingly become well-known. In Wang Bos poem “Standing Amongst Mountains,” he wrote, “Chang Jiang is rolling eastward, and I have been stranded outside for too long.” Similarly, in Li Bais poem, he wrote, “His lessening sail is lost in the boundless blue sky, where I see but the endless Chang Jiang rolling by,” and so on.

The Yangtze River makes its way into poetry, and poetry also influences the Yangtze River. Poetry derives from the Yangtze, and the Yangtze Rivers name spreads far and wide due to poetry. Ever since the existence of Chinese poetry, the Yangtze River has been a perennial source of inspiration.

Its important to note that over the course of more than a thousand years, “Chang Jiang” has become a term symbolizing the Chinese nation. However, its name wasnt designated by any emperor; it evolved naturally. Literati played a role in popularizing it, but they probably werent its initial creators.

Speculatively, the original creators might have been fishermen or hunters. As they followed the river downstream, seeking sustenance from its waters and vegetation, they might have exclaimed, “Magnificent, the river; lengthy, the river!”

Yes, who could understand the Yangtze River better than them?

Later, as spoken language transformed into written records, these unknown figures of antiquity quickly faded into oblivion.

The Yangtze River is too long, and in ancient times, transportation often faced barriers. To get people to understand the Yangtze River in its entirety was impossible. So, residents and laborers along different sections of the river casually gave those segments names, leading to a plethora of local names. These appellations were derived from ancient toponyms or the distinctive features of certain river sections, imbuing them with rich local geographical characteristics.