寄主植物对桑寄生植物叶片功能性状的影响

苏国发, 张玲

寄主植物对桑寄生植物叶片功能性状的影响

苏国发1,2, 张玲2*

(1. 云南大学生态学与环境学院,昆明 650000;2. 中国科学院西双版纳热带植物园热带森林生态学重点实验室,云南 勐腊 666303)

为了解寄生植物叶片功能性状的差异及其影响因素,研究了西双版纳地区寄主植物对3种桑寄生植物叶片功能性状的影响,并分析了桑寄生植物与寄主植物叶片功能性状的相关性。结果表明,不同寄主植物的相同寄生植物叶片功能性状存在显著差异,来自7种寄主植物的五蕊寄生()的叶片含水量(61.2%~70.1%)、氮含量(9.6~16.0 g/kg)、碳氮比(30.8~48.5)以及缩合单宁含量(3.3%~11.0%)等性状的差异较大;从4种寄主植物上获取的澜沧江寄生(var.)的叶片含水量(60.0%~71.7%)、碳含量(431.3~502.3 g/kg)和缩合单宁含量(3.8%~9.9%)等性状也呈现较大种间差异,而在2种寄主植物上的离瓣寄生()的叶片功能性状没有显著差异。桑寄生植物与寄主植物的叶片含水量、总碳含量、总氮含量、碳氮比和缩合单宁含量呈显著的正相关。寄主植物作为桑寄生植物营养物质的主要来源,会影响桑寄生植物叶片的相应功能性状。桑寄生植物能从寄主植物获取部分的水、碳、氮以及缩合单宁,但对不同元素的获取能力因寄主种类不同而有所差别。

桑寄生;寄生植物;叶片功能性状;寄生-寄主植物关系;化学性状

植物功能性状是指可以从个体水平上测量的、执行生态功能的形态、生理、生化、行为以及物候等特征,这些特征通过影响植物生长、发育和繁殖等生活史过程直接或间接影响植物的适合度和生态适应策略[1–2]。植物的功能性状受到环境因素、生物因素、遗传因素、个体发育,以及人为干扰等诸多因素的影响[3–7]。这些生物和非生物因素导致植物功能性状的改变会影响植物与其他生物间的相互作用关系,如植物-植食性动物、植物-传粉者、植物-种子散布者以及植物-寄生植物等互作网络的构建和维持[8–11]。其中,植物叶片功能性状是介导植物-病原体、植物-植食性动物相互作用的重要动力[12–16], 尤其叶片的物理防御、化学防御以及补偿等性状是调控植物与植食性动物相互作用的重要因素[17–22]。了解植物叶片功能性状差异以及影响因素对探究植物与其他生物间的相互作用具有重要的意义。

桑寄生植物(mistletoe)是一类隶属于檀香目的半寄生性气生灌木,主要包括桑寄生科(Loranthaceae)、槲寄生科(Viscaeae)、檀香科(Santalaceae)、羽毛果科(Misodendraceae)和榄仁檀科(Amphorogynaceae),其中桑寄生科和槲寄生科植物约占98%[23–25]。桑寄生植物分布范围广泛,尤其在热带雨林、亚热带常绿阔叶林、温带森林以及北方针叶林中较为常见[26]。根据寄主范围,桑寄生植物可以分泛性桑寄生和专性桑寄生。泛性桑寄生植物在一定分布范围内可以寄生到多种寄主植物上,而专性桑寄生则只寄生少数几种寄主植物。桑寄生植物在森林生态系统中发挥着重要的资源调控作用[26],在群落中与寄主植物、传粉者、种子散布者以及植食性动物形成了各种复杂的生态网络关系,具有重要生态调节功能[27]。

桑寄生植物的叶片富含营养,是许多植食动物重要的食物资源。虽然桑寄生植物自身能进行光合作用合成所需的有机物,但所需水分和矿质元素以及部分有机物是通过吸器从寄主身上获取[26,28]。因此,桑寄生植物的生理形态特征在很大程度上受到寄主植物的影响。Watson提出“寄主质量假说”,认为寄主植物的质量是决定桑寄生植物空间分布格局的重要因素[29]。但关于桑寄生植物叶片的功能性状是否受到寄主植物的影响鲜有探究。探究不同寄主上桑寄生植物叶片功能性状差异、分布模式以及影响因素,有助于了解桑寄生植物与植食性动物间的互作关系[30]。本研究以西双版纳热带植物园分布的3种桑寄生(五蕊寄生、澜沧江寄生以及离瓣寄生)及其相关寄主植物为研究对象,探究不同寄主植物上的相同桑寄生植物的叶片功能性状差异,及桑寄生植物与寄主植物的叶片功能性状间的相关性,为桑寄生-寄主植物间相互作用提供科学数据,并为寄主介导的桑寄生植物与植食性昆虫互作的研究提供新的案例。

1 材料和方法

1.1 研究区概况

研究地点位于西双版纳勐腊县勐仑镇中国科学院西双版纳热带植物园(后简称植物园,21°55′ N, 101°15′ E)。海拔541 m,属热带季风气候,干湿季明显,可分为干热季(3—5月)、雨季(6—10月)和雾凉季(11—翌年3月),雨季气候湿润,雨水充足; 干热季气候干燥,降水少,年均温高于21.5 ℃,年降水量为1 500 mm,年相对湿度为86%,土壤为砖红壤[31]。

1.2 材料

选取植物园内分布的3种桑寄生植物:五蕊寄生()、澜沧江寄生(var.)和离瓣寄生()及其寄主植物为研究对象(表1),考虑到试验观察及操作因素,所选寄主植物为灌木至小乔木,树高均在8 m以下。五蕊寄生为桑寄生科五蕊寄生属植物,是一种典型的泛性寄生性半寄生灌木,叶通常互生或近对生,侧脉羽状,具叶柄,果实成熟期为4—6月,主要靠鸟类散布种子,其中纯色啄花鸟是主要的种子散布者。在西双版纳地区五蕊寄生寄主范围最广,常寄生于杧果()、橡胶树()、榕属()、木棉()等360多种植物[32],对寄主植物造成一定程度的伤害,严重时导致寄主死亡。澜沧江寄生为桑寄生科梨果寄生属,是短柄梨果寄生的变种,花被黄褐色绒毛,果梨形,主要靠鸟类散布种子,分布于海拔500~1 300 m的山地常绿阔叶林中,寄生在石榴属()、柿属()、蒲桃属()、木姜子属()等植物上,寄主植物多达86种[33]。离瓣寄生为灌木,枝叶均无毛,叶对生,花序为总状花序,果实为椭圆状,主要靠鸟类散布种子。离瓣寄生的寄主范围相对较窄,寄主植物可达35种[33]。

表1 桑寄生植物及其寄主植物

1.3 方法

2021年6—7月,对桑寄生植物和寄主植物叶片的7个与植物营养质量或防御相关的性状进行测量,包括叶片的硬度、含水量、比叶面积、氮含量、碳含量、C/N以及缩合单宁含量[34–36]。取被桑寄生感染的每种寄主植物3棵,然后用高枝剪从不同的方位分别采取了桑寄生植物和寄主植物完全展开没有昆虫取食或受到机械损伤的叶片,然后用塑料自封袋包装,标上记号,每棵植物选取20片叶, 带回实验室。用电子天平称量每片叶的鲜质量, 用游标卡尺测量叶片厚度,用专门测量叶片硬度的仪器leaf punch测量硬度。在测量叶片的厚度和硬度时,尽量避开主脉,且每片叶从不同的部位测量3次后取平均值;然后用扫描仪对叶片进行扫描并用imageJ软件计算叶面积。然后将叶片放置75 ℃烘箱中烘72 h,称量干质量,计算叶片含水量和比叶面积,含水量=(鲜质量-干质量)/干质量×100%,比叶面积=干质量/叶面积。将烘干的叶片磨碎,过100目筛,用碳、氮含量元素分析仪进行测定碳、氮含量;缩合单宁含量使用国标高粱单宁含量的测定方法(GB/T 15686—2008)测定。

1.4 数据分析

先对数据进行正态性和方差齐次性检验,对不满足要求的数据进行适当的转化,然后进行方差分析。叶片总氮含量和单宁含量均进行对数转化以达到正态性要求。采用双因素方差分析(Two-Way ANOVA)桑寄生植物种类和寄主植物种类对桑寄生植物叶片功能性状的影响,然后对受到寄主植物影响的指标用R软件包(emmeans)进行事后多重比较检验。使用线性模型(linear model, LM)分析桑寄生植物叶片功能性状与寄主植物叶片功能性状的相关性分析,并计算寄主植物功能性状对桑寄生植物叶片功能性状的拟合系数2,然后用R软件包(ggplot2)绘制相关性图。所有的数据分析以及绘图均在R.4.03上完成。

2 结果和分析

2.1 寄主植物对桑寄生植物叶片功能性状的影响

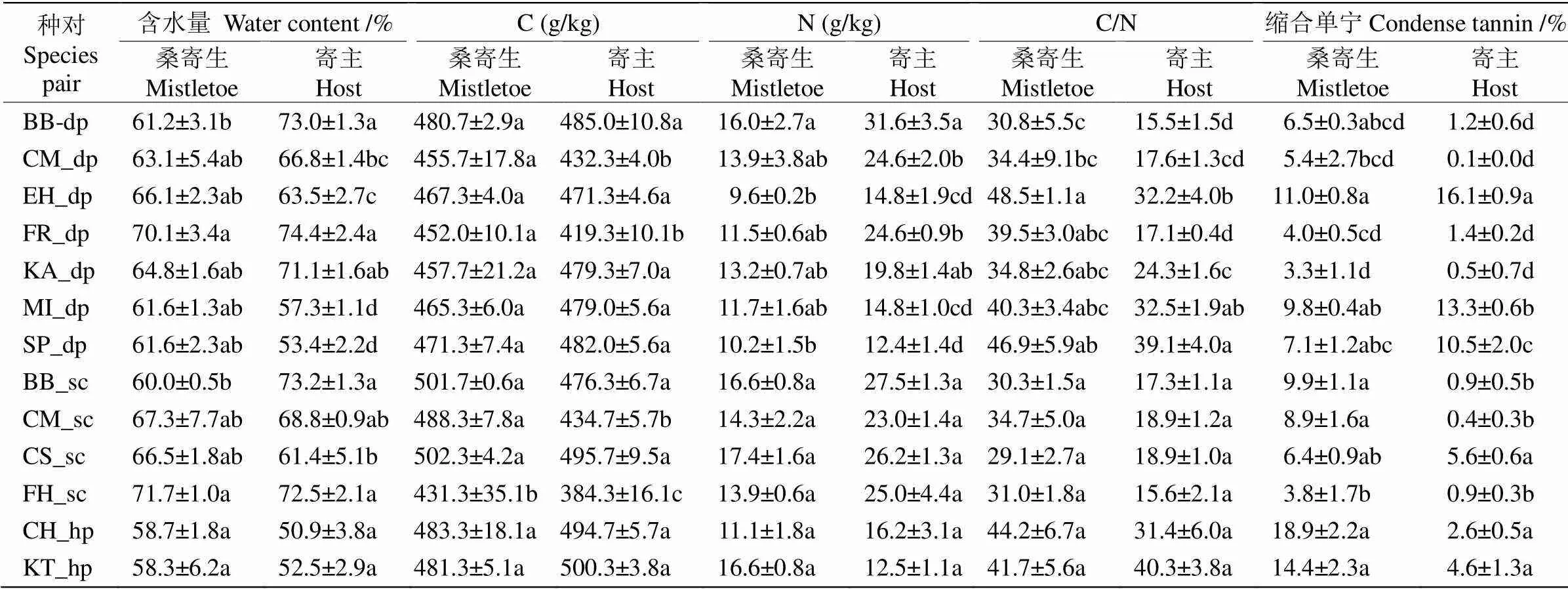

桑寄生植物叶片的硬度、比叶面积没有受到桑寄生植物种类的显著影响,但桑寄生植物叶片的含水量、总碳含量(C)、总氮含量(N)、C/N、缩合单宁含量均受到桑寄生植物种类和寄主植物种类的影响(表2)。寄生在菩提树()上的五蕊寄生叶片含水量显著高于寄生在红花羊蹄甲()上的,寄生在对叶榕()上的澜沧江寄生叶片含水量显著高于寄生在红花羊蹄甲的,而寄生在狭叶桂()和红光树()上的离瓣寄生的叶片含水量没有显著差异。寄生在对叶榕上的澜沧江寄生叶片C含量低于寄生在红花羊蹄甲、普洱茶(var.)以及柚()上的,而寄生在不同寄主植物上的五蕊寄生和离瓣寄生的叶片C含量没有显著变化。寄生在红花羊蹄甲上的五蕊寄生叶片N含量显著高于寄生在水石榕()、假多瓣蒲桃()上的,但寄生在不同寄主植物上的澜沧江寄生和离瓣寄生的叶片N含量没有显著变化。寄生在水石榕和假多瓣蒲桃上的五蕊寄生叶片C/N显著高于寄生在红花羊蹄甲上的。寄生在水石榕上的五蕊寄生叶片缩合单宁含量显著高于寄生在蕊木()、对叶榕和柚上,寄生在对叶榕上的澜沧江寄生叶片缩合单宁含量显著低于寄生在柚、红花羊蹄甲上的叶片缩合单宁含量,而离瓣江寄生的叶片缩合单宁含量在2种寄主植物上没有显著变化(表3)。

表2 桑寄生植物种类和寄主植物种类对桑寄生植物叶片功能性状的影响

*:<0.05; **:<0.01; ***:<0.001.

表3 桑寄生植物和寄主植物的叶片功能性状

BB: 红花羊蹄甲; CM: 柚; EH: 水石榕; FR: 菩提树; KA: 蕊木; MI: 杧果; SP: 假多瓣蒲桃; CS:普洱茶; FH: 对叶榕; CH:狭叶桂; KT: 红光树; dp: 五蕊寄生; sc: 澜沧江寄生; hp: 离瓣寄生。同列数据后不同字母表示差异显著(<0.05)。

BB:; CM:; EH:; FR:; MI:; SP:; CS:var.; FH:; CH:; KT:; dp:; sc:var.; hp:. Data followed different letters within column indicate significant differences at 0.05 level by Tukey test.

2.2 桑寄生植物与寄主植物叶片功能性状的关系

桑寄生植物叶片的功能性状多数受到寄主植物的影响。除叶片厚度、比叶面积外,桑寄生植物与寄主植物的叶片含水量(2=0.20)、C含量(2=0.39)、N含量(2=0.49)、C/N (2=0.45)和缩合单宁含量(2=0.23)均呈显著正相关关系(图1)。

图1 桑寄生植物与寄主植物叶片功能性状的相关性

3 结论和讨论

以往对桑寄生植物与寄主植物功能性状的研究,主要是从生理学角度探讨桑寄生植物与寄主植物间的碳、氮、水分关系[28,37–39]。有研究用稳定性同位素C13和N14探讨了桑寄生植物与寄主植物间的碳、氮关系,表明两者的C13和N14呈显著的正相关关系[39–41];此外,对桑寄生植物和寄主植物的叶片C、N含量和C/N的研究也有相似结果[39–42]。本研究结果表明,桑寄生植物所需的碳、氮元素主要来自寄主植物。“氮寄生假说”认为氮元素是桑寄生植物的限制性资源,寄主植物氮含量对桑寄生植物的寄生和生存极为重要;而“拟态假说”认为富含氮的桑寄生植物为避免被植食性动物取食,模拟寄主植物叶片[41]。寄主植物的营养质量是影响桑寄生植物生命活动和空间分布格局的重要因素[29]。本研究结果支持Watson[29]的寄主质量假说,同时也部分支持拟态假说[41]。不同寄主植物所含的氮含量不同,提供给寄生植物的碳、氮也不同,豆科固氮植物红花羊蹄甲叶片的N含量最高、C/N最小,寄生的五蕊寄生和澜沧江寄生叶片的N含量也是最高、C/N最小;对叶榕的叶片C含量较低,寄生的澜沧江寄生的叶片C含量也最小。

许多研究表明,桑寄生植物的叶片蒸腾速率比寄主植物高,气孔调节能力差,叶片水势低于寄主植物,因此能够从寄主植物上不断获取水分和养分[43]。本研究结果表明,桑寄生植物的叶片含水量主要来自寄主植物,但是对寄主水分的吸取能力受桑寄生植物种类和寄主植物种类的影响。此外,植物叶片中的缩合单宁对抵抗各种生物胁迫,提高植物适合度极为重要,不同寄主植物上的五蕊寄生和澜沧江寄生叶片的缩合单宁含量均表现出显著的差异, 且当寄主植物缩合单宁含量很少时,桑寄生植物的也比寄主高。当寄主植物的缩合单宁含量较高时,五蕊寄生的也较高。由此推测,桑寄生植物缩合单宁的合成能力较强,即使在寄主植物的缩合单宁含量很少的情况下也能合成一定的缩合单宁,但当寄主植物的缩合单宁合成能力比寄生植物强时,主要从寄主植物上获取缩合单宁。目前,关于桑寄生植物和寄主植物次生代谢物的研究中,桑寄生植物的次生代谢物多大程度来自寄主植物或自身合成还没有进行系统的研究,本研究也无法充分证实多大程度桑寄生植物靠自身合成缩合单宁,多大程度从寄主中获取,这有待深入探究。

综上,寄主植物作为桑寄生植物的重要营养物质来源和生长环境,不同寄主植物所能提供寄生植物的营养质量和生境不同,导致桑寄生植物功能性状在不同寄主植物存在明显的差异,尤其是桑寄生植物的化学性状受到寄主植物影响较大。寄主植物对桑寄生植物的影响是否介导桑寄生植物与其他生物间的相互作用亟待探究。

[1] VIOLLE C, NAVAS M L, VILE D, et al. Let the concept of trait be functional! [J]. Oikos, 2007, 116(5): 882–892. doi: 10.1111/j.0030- 1299.2007.15559.x.

[2] GEBER M A, GRIFFEN L R. Inheritance and natural selection on functional traits [J]. Int J Plant Sci, 2003, 164(S3): S21–S42. doi: 10. 1086/368233.

[3] FRANCO A C, BUSTAMANTE M, CALDAS L S, et al. Leaf functional traits of Neotropical savanna trees in relation to seasonal water deficit [J]. Trees, 2005, 19(3): 326–335. doi: 10.1007/s00468- 004-0394-z.

[4] OSBORNE C P, CHARLES-DOMINIQUE T, STEVENS N, et al. Human impacts in African savannas are mediated by plant functional traits [J]. New Phytol, 2018, 220(1): 10–24. doi: 10.1111/nph.15236.

[5] ZAMBRANO J, GARZON-LOPEZ C X, YEAGER L, et al. The effects of habitat loss and fragmentation on plant functional traits and func- tional diversity: What do we know so far? [J]. Oecologia, 2019, 191(3): 505–518. doi: 10.1007/s00442-019-04505-x.

[6] ZHANG S H, ZHANG Y, XIONG K N, et al. Changes of leaf functional traits in karst rocky desertification ecological environment and the driving factors [J]. Glob Ecol Conserv, 2020, 24: e01381. doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e01381.

[7] MENEZES J, GARCIA S, GRANDIS A, et al. Changes in leaf functional traits with leaf age: When do leaves decrease their photosynthetic capacity in Amazonian trees? [J]. Tree Physiol, 2022, 42(5): 922–938. doi: 10.1093/TREEPHYS/TPAB042.

[8] SCHWARTZ G, HANAZAKI N, SILVA M B, et al. Evidence for a stress hypothesis: Hemiparasitism effect on the colonization ofA. Juss. (Uphorbiaceae) by galling insects [J]. Acta Amazon, 2003, 33(2): 275–280. doi: 10.1590/1809-4392200332280.

[9] BURGHARDT K T. Nutrient supply alters goldenrod’s induced response to herbivory [J]. Funct Ecol, 2016, 30(11): 1769–1778. doi: 10.1111/ 1365-2435.12681.

[10] DAVIDSON-LOWE E, SZENDREI Z, ALI J G. Asymmetric effects of a leaf-chewing herbivore on aphid population growth [J]. Ecol Entomol, 2019, 44(1): 81–92. doi: 10.1111/een.12681.

[11] CASTAGNEYROL B, KOZLOV M V, POEYDEBAT C, et al. Asso- ciational resistance to a pest insect fades with time [J]. J Pest Sci, 2020, 93(1): 427–437. doi: 10.1007/s10340-019-01148-y.

[12] KLAIBER J, NAJAR-RODRIGUEZ A J, PISKORSKI R, et al. Plant acclimation to elevated CO2affects important plant functional traits, and concomitantly reduces plant colonization rates by an herbivorous insect [J]. Planta, 2013, 237(1): 29–42. doi: 10.1007/s00425-012-1750-7.

[13] ZHENG S X, LI W H, LAN Z C, et al. Functional trait responses to grazing are mediated by soil moisture and plant functional group identity [J]. Sci Rep, 2015, 5: 18163. doi: 10.1038/srep18163.

[14] DESCOMBES P, KERGUNTEUIL A, GLAUSER G, et al. Plant physical and chemical traits associated with herbivory in situ and under a warming treatment [J]. J Ecol, 2020, 108(2): 733–749. doi: 10.1111/ 1365-2745.13286.

[15] RUIZ-GUERRA B, GARCÍA A, VELÁZQUEZ-ROSAS N, et al. Plant-functional traits drive insect herbivory in a tropical rainforest tree community [J]. Perspect Plant Ecol Evol Syst, 2021, 48: 125587. doi: 10.1016/j.ppees.2020.125587.

[16]EKHOLM A, FATICOV M, TACK A J M, et al. Herbivory in a changing climate: Effects of plant genotype and experimentally induced variation in plant phenology on two summer-active lepidopteran herbivores and one fungal pathogen [J]. Ecol Evol, 2022, 12(1): e8495. doi: 10.1002/ ECE3.8495.

[17] AGRAWAL A A. Macroevolution of plant defense strategies [J]. Trends Ecol Evol, 2007, 22(2): 103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2006.10.012.

[18] HANLEY M E, LAMONT B B, FAIRBANKS M M, et al. Plant structural traits and their role in anti-herbivore defence [J]. Perspect Plant Ecol Evol Syst, 2007, 8(4): 157–178. doi: 10.1016/j.ppees.2007. 01.001.

[19] CARMONA D, LAJEUNESSE M J, JOHNSON M T J. Plant traits that predict resistance to herbivores [J]. Funct Ecol, 2011, 25(2): 358–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2010.01794.x.

[20] ESKELINEN A, HARRISON S, TUOMI M. Plant traits mediate consumer and nutrient control on plant community productivity and diversity [J]. Ecology, 2012, 93(12): 2705–2718. doi: 10.1890/12-0393.1.

[21] LORANGER J, MEYER S T, SHIPLEY B, et al. Predicting inverte- brate herbivory from plant traits: Evidence from 51 grassland species in experimental monocultures [J]. Ecology, 2012, 93(12): 2674–2682. doi: 10.1890/12-0328.1.

[22] IBANEZ S, MANNEVILLE O, MIQUEL C, et al. Plant functional traits reveal the relative contribution of habitat and food preferences to the diet of grasshoppers [J]. Oecologia, 2013, 173(4): 1459–1470. doi: 10.1007/s00442-013-2738-0.

[23] AUKEMA J E. Vectors, viscin, and Viscaceae: Mistletoes as parasites, mutualists, and resources [J]. Front Ecol Environ, 2003, 1(4): 212–219. doi: 10.1890/1540-9295(2003)001[0212:VVAVMA]2.0.CO;2.

[24] MATHIASEN R L, NICKRENT D L, SHAW D C, et al. Mistletoes: Pathology, systematics, ecology, and management [J]. Plant Dis, 2008, 92(7): 988–1006. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-92-7-0988.

[25] MAUL K, KRUG M, NICKRENT D L, et al. Morphology, geographic distribution, and host preferences are poor predictors of phylogenetic relatedness in the mistletoe genusL. [J]. Mol Phylogenet Evol, 2019, 131: 106–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2018.10.041.

[26] WATSON D M. Mistletoe: A keystone resource in forests and wood- lands worldwide [J]. Annu Rev Ecol Syst, 2001, 32(1): 219–249. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.32.081501.114024.

[27]MARCH W A, WATSON D M. The contribution of mistletoes to nutrient returns: Evidence for a critical role in nutrient cycling [J]. Aust Ecol, 2010, 35(7): 713–721. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9993.2009.02056.x.

[28] GLATZEL G, GEILS B W. Mistletoe ecophysiology: Host-parasite interactions [J]. Botany, 2009, 87(1): 10–15. doi: 10.1139/B08-096.

[29] WATSON D M. Determinants of parasitic plant distribution: The role of host quality [J]. Botany, 2009, 87(1): 16–21. doi: 10.1139/B08-105.

[30] GRIEBEL A, WATSON D, PENDALL E. Mistletoe, friend and foe: Synthesizing ecosystem implications of mistletoe infection [J]. Environ Res Lett, 2017, 12(11): 115012. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/aa8fff.

[31] CAO M, ZOU X M, WARREN M, et al. Tropical forests of Xishuang- banna, China [J]. Biotropica, 2006, 38(3): 306–309. doi: 10.1111/j. 1744-429.2006.00146.x.

[32] XIAO L Y, PU Z H. An investigation on the harm of Loranthaceae in Xishuangbanna, Yunnan [J]. Acta Bot Yunnan, 1988, 10(4): 423–432. [肖来云, 普正和. 西双版纳桑寄生植物的危害调查 [J]. 云南植物研究, 1988, 10(4): 423–432.]

[33] WANG X N, ZHANG L. Species diversity and distribution of mist- letoes and hosts in four different habitats in Xishuangbanna, southwest China [J]. J Yunnan Univ (Nat Sci), 2017, 39(4): 701–711. [王煊妮, 张玲. 西双版纳4种生境下的桑寄生与寄主植物多样性及分布特点[J]. 云南大学(自然科学版), 2017, 39(4): 701–711. doi: 10.7540/j.ynu. 20160542.]

[34] AGRAWAL A A, FISHBEIN M. Plant defense syndromes [J]. Ecology, 2006, 87(Suppl 7): S132–S149. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2006)87[132: PDS] 2.0.CO;2.

[35] SALMINEN J P, KARONEN M. Chemical ecology of tannins and other phenolics: We need a change in approach [J]. Funct Ecol, 2011, 25(2): 325–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2010.01826.x

[36] RICHARDS L A, GLASSMIRE A E, OCHSENRIDER K M, et al. Phytochemical diversity and synergistic effects on herbivores [J]. Phyto- chem Rev, 2016, 15(6): 1153–1166. doi: 10.1007/s11101-016-9479-8.

[37] DALAL R C, STRONG W M, COOPER J E, et al. Relationship between water use and nitrogen use efficiency discerned by13C discrimination and15N isotope ratio in bread wheat grown under no-till [J]. Soil Till Res, 2013, 128: 110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.still.2012.07.019.

[38] TENNAKOON K U, CHAK W H, BOLIN J F. Nutritional and isotopic relationships of selected Bornean tropical mistletoe-host associations in Brunei Darussalam [J]. Funct Plant Biol, 2011, 38(6): 505–513. doi: 10. 1071/FP10211.

[39] WANG L X, KGOPE B, D’ODORICO P, et al. Carbon and nitrogen parasitism by a xylem-tapping mistletoe () along the Kalahari Transect: A stable isotope study [J]. Afr J Ecol, 2008, 46 (4): 540–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2028.2007.00895.x.

[40] CERNUSAK L A, PATE J S, FARQUHAR G D. Oxygen and carbon isotope composition of parasitic plants and their hosts in southwestern Australia [J]. Oecologia, 2004, 139(2): 199–213. doi: 10.1007/s00442- 004-1506-6.

[41] SCALON M C, WRIGHT I J. A global analysis of water and nitrogen relationships between mistletoes and their hosts: Broad-scale tests of old and enduring hypotheses [J]. Funct Ecol, 2015, 29(9): 1114–1124. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.12418.

[42] BANNISTER P, STRONG G L. Carbon and nitrogen isotope ratios, nitrogen content and heterotrophy in New Zealand mistletoes [J]. Oecologia, 2001, 126(1): 10–20. doi: 10.1007/s004420000495.

[43] HE X F, WANG S W, KÖRNER C, et al. Water and nutrient relations of mistletoes at the drought limit of their hosting evergreen oaks in the semiarid upper Yangtze region, SW China [J]. Trees, 2021, 35(2): 387– 394. doi: 10.1007/s00468-020-02039-x.

[44] MATTHIES D. Closely related parasitic plants have similar host requirements and related effects on hosts [J]. Ecol Evol, 2021, 11(17): 12011–12024. doi: 10.1002/ece3.7967.

Effects of Host Plants on Leaf Functional Traits of Mistletoes

SU Guofa1,2, ZHANG Ling2*

(1. School of Ecology and Environmental Science, Yunnan University, Kunming 650000, China; 2. Key Laboratory of Tropical Forest Ecology, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanic Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences,Mengla 666303, Yunnan, China)

In order to understand the differences of leaf functional traits of parasitic plants and their influencing factors, the effects of host plants on leaf functional traits of three mistletoes in Xishuangbanna were studied, and the correlation between leaf functional traits of mistletoes and host plants was analyzed. The results showed that there were significant differences in leaf functional traits of the same mistletoes from different host plants. The leaf water content (61.2%-70.1%), nitrogen concentration (9.6-16.0 g/kg), C/N (30.8-48.5), and condense tannin content (3.3%-11.0%) ofdisplayed significant differences among its seven host species. Besides, the leaf water content (60.0%-71.7%), carbon concentration (431.3-502.3 g/kg), and condense tannin content (3.8%-9.9%) ofvar.also showed significant difference among its four host species, but there was no significant difference in functional traits offrom its two host species. In general, leaf water content, carbon concentration, nitrogen concentration, C/N, and condense tannin content had positive significant correlation between mistletoes and their host plants. Therefore, it was concluded that host plants as nutrient resource could influence leaf functional traits of mistletoe. Mistletoe obtains water, carbon, nitrogen, and condense tannin from the host plant; but the ability to obtain different elements varies with host species.

Mistletoe; Parasitic plant; Leaf functional trait; Host-parasitic plant relation; Chemical traits

10.11926/jtsb.4627

2022–02–24

2022–04–27

国家自然科学基金项目(31670393)资助

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31670393).

苏国发(1996年生),男,硕士研究生,主要从事植物生态学和动植物关系的研究。

. E-mail: zhangl@xtbg.org.cn

——“单宁”