Exercise interventions for patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus: A narrative review with practical recommendations

Fernando Martin-Rivera, Sergio Maroto-Izquierdo, David García-López, Jesús Alarcón-Gómez

Fernando Martin-Rivera, Jesús Alarcón-Gómez, Department of Physical Education and Sports, University of Valencia, Valencia 46010, Spain

Sergio Maroto-Izquierdo, David García-López, Department of Health Sciences, Miguel de Cervantes European University, Valladolid 47012, Spain

Abstract Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) is a chronic endocrine disease that results from autoimmune destruction of pancreatic insulin-producing B cells, which can lead to microvascular (e.g., retinopathy, neuropathy, and nephropathy) and macrovascular complications (e.g., coronary arterial disease, peripheral artery disease, stroke, and heart failure) as a consequence of chronic hyperglycemia. Despite the widely available and compelling evidence that regular exercise is an efficient strategy to prevent cardiovascular disease and to improve functional capacity and psychological well-being in people with T1DM, over 60% of individuals with T1DM do not exercise regularly. It is, therefore, crucial to devise approaches to motivate patients with T1DM to exercise, to adhere to a training program, and to inform them of its specific characteristics (e.g., exercise mode, intensity, volume, and frequency). Moreover, given the metabolic alterations that occur during acute bouts of exercise in T1DM patients, exercise prescription in this population should be carefully analyzed to maximize its benefits and to reduce its potential risks.

Key Words: Type 1 diabetes mellitus; Exercise; Resistance training; High-intensity interval training; Aerobic training; Quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) is a chronic autoimmune disease that results from the immunological destruction of pancreatic insulin-producing B cells, which can lead to microvascular (e.g., retinopathy, neuropathy, and nephropathy) and macrovascular complications (e.g., coronary arterial disease, peripheral artery disease, stroke, and heart failure) as a consequence of chronic hyperglycemia[1]. According to the International Diabetes Federation and World Health Organization, 25-45 million adults (> 20-years-old) suffer from T1DM worldwide[2]. In addition, it is estimated that the number of people with T1DM in the world will increase 25% by 2030[3].

Despite the widely available and compelling evidence that regular exercise is an efficient strategy to prevent cardiovascular disease and to improve functional capacity and psychological well-being in people with T1DM, over 60% of individuals with T1DM do not exercise regularly[4,5]. Lack of time, fear of a hypoglycemic event, and loss of glycemic control due to inadequate knowledge of exercise variable management are the main barriers to increasing physical activity in patients with T1DM[6]. It is, therefore, crucial to devise approaches to motivate patients with T1DM to exercise, to adhere to a training program, and to inform them of the specific characteristics of the training program (e.g., exercise mode, intensity, volume, frequency). Moreover, given the metabolic alterations that occur during acute bouts of exercise in T1DM patients, exercise prescription in this population should be carefully analyzed to maximize benefits and to reduce potential risks.

AEROBIC EXERCISE AND T1DM

Aerobic exercise guidelines and benefits

Aerobic exercise is defined as continuous physical exercise of moderate intensity (50%-70% of maximum heart rate) and of high volume (> 20-30 min), which involves large muscles and requires the presence of oxygen to obtain energy[7]. Examples of this exercise mode are cycling, swimming, walking, or running performed at a moderate intensity[7]. This type of exercise has traditionally been recommended for specific populations, such as T1DM. In fact, the American Diabetes Society recommends at least 150 min per week of aerobic exercise for better glycemic regulation and improvement of the disease[8].

Aerobic exercise has positive effects on T1DM patient health, improving insulin sensitivity, body composition, endothelial, pulmonary, and cardiac function, as well as cardiorespiratory fitness[7] (Figure 1). It is obvious that aerobic exercise training may robustly protect people with T1DM from several complications associated with cardiovascular disease, the main cause of mortality and morbidity in this population[9].

Figure 1 Main benefits of aerobic training, high-intensity interval training, and resistance exercise in type 1 diabetes mellitus patients.

Aerobic exercise in T1DM population: General considerations

T1DM patients must consider various factors before performing continuous moderate-intensity exercise safely. Before starting the training program, certain factors must be considered. The patient’s physical condition level/capacity, previous exercise experience, the duration and intensity of the current exercise, blood glucose at that given moment, the dose of pre-exercise administered insulin, and finally the general diet in the preceding period[4,10]. Exogenously administered insulin allows glucose to enter into muscle cells, consequently generating the energy to maintain movement since the entire metabolism during and after any given exercise will be altered.

During aerobic exercise, blood glucose enters the muscles to meet the needs for increased energy generation in the presence of oxygen initiating aerobic glycolysis. Physical exercise can increase muscle glucose demand and consumption up to 50-fold through an increase in insulin sensitivity and an increase in insulin-independent muscle glucose transport[11]. Thus, insulin secretion in people without a T1DM pathology is reduced. This happens precisely to compensate for the increase in insulin sensitivity and glucose transport caused by physical exercise itself, so the reduction in blood insulin does not restrict the supply of glucose to the muscles[4].

Nevertheless, to maintain metabolic homeostasis and to avoid hypoglycemia, different mechanisms are activated that regulate blood glucose concentration. Four metabolic pathways are triggered to ensure energy production: (1) Glucose mobilization (from glycogen stores) from the liver; (2) fatty acid mobilization from adipose tissue; (3) gluconeogenesis (production of new glucose molecules) from noncarbohydrate (CHO) precursors (amino acids, lactate, and glycerol); and (4) blocking glucose entry into cells and promoting fatty acids (an alternative is oxidation for energy generation) to be used in energy generation[12]. These mechanisms are orchestrated by glucagon, cortisol, growth hormone (GH), epinephrine, and norepinephrine. When the blood glucose concentration decreases, these hormones respond by activating mechanisms to restore the imminent hypoglycemia. Glucagon increases liver glucose production and stimulates gluconeogenesis, while cortisol-GH balance stimulates gluconeogenesis and fatty acid mobilization. Epinephrine and norepinephrine (catecholamines) are responsible for the catabolism of glycogen (glycogenolysis) and lipids (lipolysis) and for reducing muscle glucose consumption. On the other hand, norepinephrine reduces insulin secretion so that it does not interfere with the increase in blood glucose caused by the aforementioned hormones[13].

Important differences in the metabolic behavior of T1DM patients during aerobic exercise must be considered. Furthermore, physical exercise response depends on exercise intensity and volume, CHO intake, as well as type and amount of exogenous insulin[4]. Unlike in the healthy population, during aerobic exercise in T1DM patients exogenous insulin cannot decrease similarly to the pattern of non-T1DM individuals due to non-insulin-dependent muscle glucose transport and insulin sensitivity increase[11]. Moreover, given the pharmacokinetics and peak action of exogenous insulin and considering that exercise intervention is usually performed between 0-4 h after insulin injection, insulin levels are unpredictable. In addition, especially when injected near currently active musculature, insulin can be rapidly absorbed by subcutaneous tissue, rapidly transferring it into the bloodstream when exercise activity is initiated with unforeseeable results[12].

The abnormally high blood insulin levels during physical exercise in T1DM result in an exaggerated entry of glucose into the musculature and the inhibition of endogenous glucose production and fatty acid mobilization mediated by cortisol, GH, glucagon, and catecholamines. Under normal conditions, these hormones act by increasing the blood glucose concentration in the face of low insulin levels, but in T1DM these hormonal mechanisms are impaired[4,12]. Consequently, an excessive drop in blood glucose concentration or even hypoglycemia (< 70 mg/dL) may occur during physical exercise, which depending on its severity can cause dizziness, fainting, and coma. Such hypoglycemic events can still occur hours after the end of physical exercise if appropriate measures are not taken.

After physical exercise, muscle glucose consumption is reduced, but insulin sensitivity remains high. This fact, together with the need to replenish muscle glycogen stores that have been consumed during physical exercise, can lead to post-exercise hypoglycemia and even occur while asleep at night as insulin sensitivity tends to be biphasic (occurring immediately after physical exercise and 7-11 h later). People with T1DM may potentially experience 42-91 hypoglycemic episodes annually. Moreover, approximately 12% of T1DM patients have at least one severe hypoglycemia episode per year[14]. The fear of these episodes makes people with T1DM unwilling to participate in this type of exercise[15].

In summary, the appropriate course of action for people with T1DM in order to be able to safely engage in aerobic physical exercise is based on ensuring an adequate CHO intake prior to physical exercise that elevates blood glucose levels to above 126 mg/dL but not over 270 mg/dL, in tandem with a reduction of insulin dosage before training to counteract the increase in insulin sensitivity and the intensification of non-insulin dependent glucose transport mechanisms occurring during physical exercise[4]. To this end, it is important to take at least two blood glucose measurements, one half an hour before and a second 10 min later. If the physical exercise is long-lasting, an extra supply of glucose and fructose will be essential during the exercise. After the end of physical exercise, insulin reduction and CHO intake is again essential to prevent post-exercise hypoglycemia[16].

When the adjustment in insulin dose and CHO intake becomes imbalanced, diabetic ketoacidosis may occur. In the presence of reduced insulin levels and a high concentration of counter-regulatory hormones such as epinephrine or glucagon, glucose is unable to enter the muscles, among other tissues, and as a result non-esterified fatty acids and glycerol are produced from the catabolism of triglycerides. Glycerol is used as a substrate in gluconeogenesis, but fatty acids catalyzed by carnitine are oxidized to ketone bodies in the liver as an alternative means of obtaining energy. Hyperketonemia may lead to serious health sequalae[17] such as dizziness, vomiting, and nausea, and when severe cerebral edema or myocardial injury may result. It is therefore imperative to adjust insulin dosages suitably to ensure safe exercise activity and avoid complications due to either excess or deficiency of the hormone[18].

High-intensity interval training and T1DM

High-intensity interval training (HIIT) is a type of physical exercise with a recent increase in popularity among fitness enthusiasts (ranked in the top 3 of world fitness trends)[19] and sport science academics alike, with almost 700 publications in PubMed. Despite this recent surge in acclaim, HIIT modalities have been employed in sports performance training since the 1920s[20]. The physiological impact of HIIT has recently been informed in both clinical and sport contexts[21]. HIIT presents a unique opportunity to obtain cardiorespiratory and metabolic benefits comparable to those obtained by classic moderate-intensity continuous training[22] through lower training volumes, addressing the main barrier (lack of time) cited by most people for not doing physical exercise. HIIT consists of performing short-to-moderate (between 8 s and 4 min) bouts of any given physical exercise (mainly endurance exercises) at high intensity (i.e., above the anaerobic threshold) interspersed by brief resting intervals performing low intensity activities such as walking or passive rest periods (ranging from 4 s to 60 s)[23].

Several different HIIT protocols have been proposed throughout the scientific literature based on exercise type, exercise intensity, volume (time duration) and number of exercise intervals, intensity and duration of rest periods, number of sets, length of each set, rest between sets, and exercise intensity during active rest periods[24]. Despite the high variability observed, the considerable majority of HIIT protocols use high-intensity exercise intervals performed between 10 s and 4 min with 30-60-s rest periods between sets. These training programs pursue the accumulation of short bouts of high-intensity exercise (> 90% of VO2max) otherwise not sustainable for long time periods, interspersing short resting periods that allow the high-exertion intervals to be completed at the desired intensity. A complete standard HIIT session usually takes/requires between 20-40 min, including rest periods, of which at least 4 min must be at high intensity (considering the sum of all intervals)[20,25,26].

The anaerobic energy production of HIIT, as high intensity intervals are usually performed above 90% of VO2max, where the initial substrates used are free ATP in the muscle fiber and phosphocreatine determine the acute responses in relation to the metabolism and endocrine system. An aerobic component is also necessary as recovery intervals depend on it[20]. Hence, HIIT has been proposed as a potentially effective tool to improve blood pressure, weight control, glucose regulation, cardiorespiratory fitness, and psychological well-being in chronic pathologies such as hypertension[27], obesity[28], metabolic syndrome[29], T2DM[30], heart failure[31], chronic obstructive pulmonary disease[32], and mental illness[33]. However, despite the benefits HIIT has demonstrated in other chronic diseases. The effect that this type of training has on people with T1DM has not yet been extensively studied[4].

High-intensity stimuli lead to an increase in catecholamine secretion, inhibiting insulin-mediated glucose consumption and accelerating gluconeogenesis. As a result, obtaining energy from glucose without the intervention of oxygen (anaerobic glycolysis), muscle fibers and blood lactate concentrations increase. This process also inhibits insulin-mediated glucose consumption and promotes glucose production by the liver. Taken together, these mechanisms contribute to a much safer glycemic regulation during and after physical exercise in people with T1DM compared with moderate-intensity aerobic exercise, preventing the occurrence of hypoglycemia[1]. In addition, oxygen consumption remains elevated and helps the subject to revert to a regular basal metabolic state after training through lactate clearance, increased cardiopulmonary function, increased body temperature, enhanced catecholamine effect, and glycogen re-synthesis, using lipids as an energy substrate[34].

Despite being an exercise mode that has been little studied in the T1DM population, HIIT seems to have positive cardiovascular and metabolic effects in people with this condition. Reported benefits include increases in VO2max, improvements in vascular function, psychological well-being, body composition, cardiac function, and antioxidant and anti-inflammatory markers, along with a reduction in the amount of insulin administered[35-40] (Figure 1). All the above, along with the prevention of hypoglycemia and the short time required can overcome the major barriers that people with T1DM present against physical exercise[6,15], positioning HIIT interventions as a useful therapy for this population, it may be a better alternative compared to aerobic or resistance exercise training, which pose a higher risk of hypoglycemia and require more time, although they are not mutually exclusive.

RESISTANCE TRAINING AND T1DM

Resistance exercise guidelines and benefits

Resistance exercise refers to the exercise mode in which muscles produce tension to accelerate, decelerate, or maintain immobility for any given resistance. This resistance could be weights, bands, or even the subject’s own bodyweight working against gravity[41]. Depending on training variable manipulation (exercise volume, intensity, mode of contraction, movement velocity, and rest intervals between sets), a specific resistance training program might result in muscle hypertrophy, strength, mechanical power, and endurance enhancements[42]. Resistance training is currently being recommended for patients with T1DM by the American Diabetes Association and the American College of Sports Medicine. The recommendation is performing on 2-3 non-consecutive training days prioritizing large muscle groups, with at least 8-10 exercises in 1-3 sets of 10-15 repetitions at an intensity ranging from 50% to 75% of one-repetition maximum[12,43].

There is a known relationship between skeletal muscle mass and higher-level functional capacity[44]. People with T1DM are susceptible to muscle mass loss and sarcopenia faster than people without this disease, even without having developed disease-specific complications[45]. Resistance training might therefore address those fundamental deficits in this population[46]. Apart from muscle mass increase, one of the main benefits of resistance training in T1DM patients is the improvement of bone density, essential in this population because hyperglycemia in T1DM patients causes bone mineral mass loss earlier than people of the same age, physical condition, and body composition[47,48]. It is also wellknown that resistance training improves body composition (i.e., reduced fat mass and increased muscle mass)[49] thus preventing the development of overweightness, lately noted as a prevalent issue in this population[50] (Figure 1). In addition to the significant improvements observed in a functional capacity after accomplishing a resistance training program, another fundamental benefit of resistance training is its impact on cardiovascular health through the improvement in the lipid profile and vascular function[49]. This is relevant for T1DM patients since cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of mortality in this population[51,52]. Moreover, an adequate resistance training program enhances functional capacity by improving daily activity functionality, preventing falls, injuries and cardiovascular diseases, and increasing independence[12,49].

Despite the lack of studies analyzing the acute response to resistance training in people with T1DM[49], it should be noted that the hormonal response and the overwhelmingly anaerobic metabolism cause a much slower reduction in glucose levels during resistance training than that occurring during aerobic exercise in people with T1DM. Similarly, resistance training is associated with a much more stable post-exercise glucose concentration in comparison to aerobic exercise (hypoglycemia during and after exercise), which would be reduced with this exercise mode[53]. The increases in catecholamine concentration during resistance training and consequently the increase in endogenous glucose production allows T1DM patients to more easily adjust exogenous insulin dosage and CHO intake than with aerobic exercise.

However, certain types of resistance training with high volume and low intensity might induce a decreased hormonal response, but resistance training with sufficiently high intensity and low volume is associated with an enhanced hormonal response, leading to higher hepatic glucose production. Moreover, an initial reduction in exogenous insulin or CHO intake before the resistance training program to prevent the drop in blood glucose is not necessary as opposed to what typically occurs with aerobic exercise. Despite this, it may still be necessary to control the hyperglycemic tendency after resistance exercise by increasing the insulin dose and postponing the intake of CHO[4]. However, the acute effect of resistance training in people with T1DM has not been elucidated yet, and more research is warranted to understand the specific underpinning mechanisms of the insulin/CHO ratio in association with different types of resistance training completed[14,49] (Figure 1).

PRACTICAL APPLICATIONS

Conditional and psychological assessment

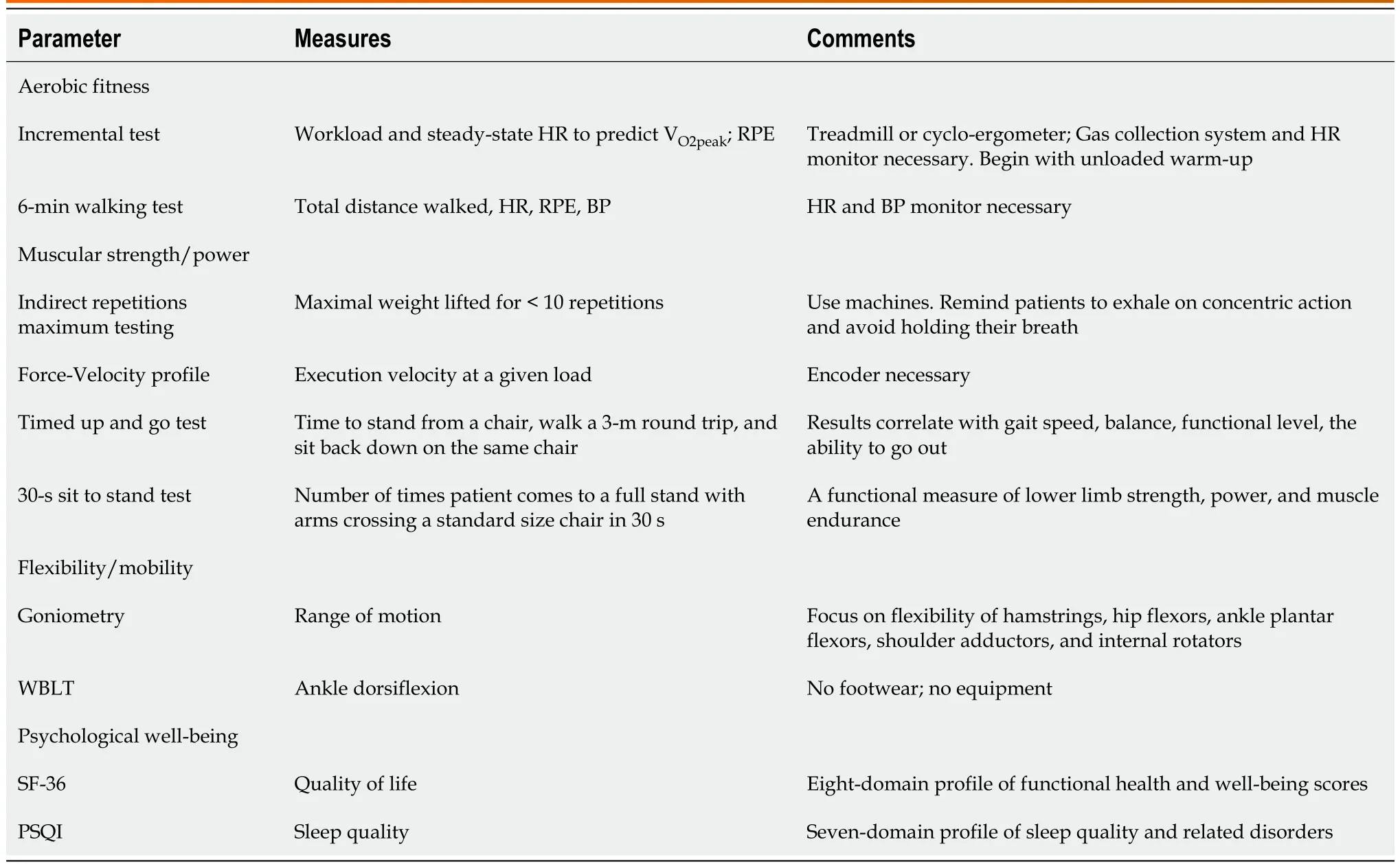

A comprehensive pre-exercise screening should be performed before designing an individualized training program for each T1DM patient. This should be preferably performed by sports science professionals with proper expertise in T1DM. Prior evaluation should include an anamnesis assessment and physical examination as well as a cardiopulmonary function test. Patients should also be screened for risk factors or presence of cardiovascular, respiratory, or metabolic disorders apart from T1DM. When the medical approval for the implementation of an individualized training program has been obtained, the patient’s cardiorespiratory, neuromuscular and functional performance should be tested (Table 1). Similarly, it is important to use tools to assess important psychological aspects such as quality of life and sleep quality, since these are issues that can affect people with T1DM (Table 1).

Table 1 Evaluation protocols in type 1 diabetes mellitus exercise programming

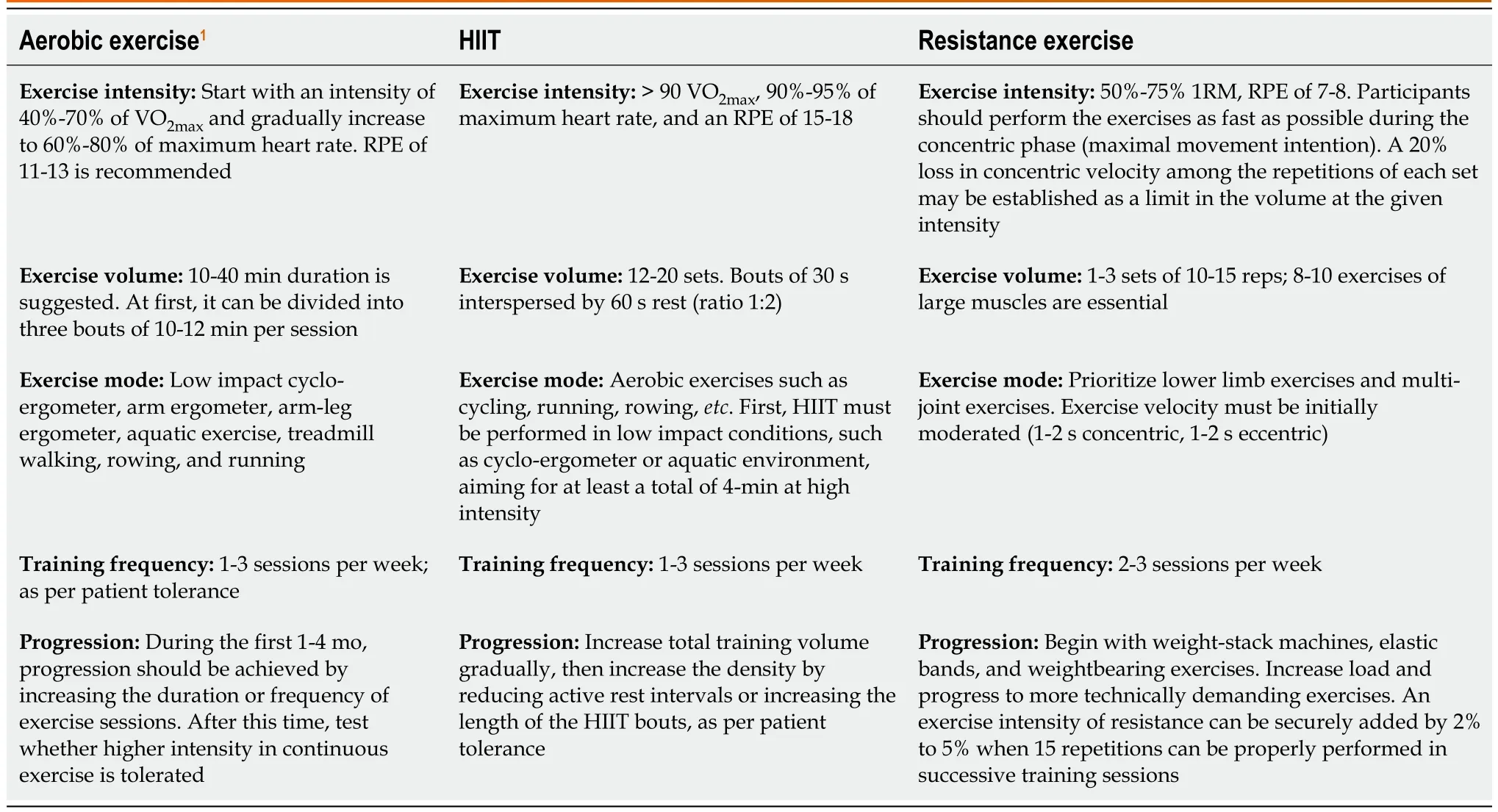

Practical recommendations for exercise prescription in T1DM patients

An individualized exercise program should be designed to address the patient’s goals (e.g., improve strength, endurance, balance, coordination,etc.) considering the patient’s baseline impairments and capabilities. The exercise program should include all the necessary training variables, such as frequency, volume, intensity, exercise mode, and precautions to be considered, prior to and after the program. It is important to bear in mind that in practice blood glucose levels may show a variable response for the same CHO-insulin adjustments. A multitude of factors, such as the food previously eaten, hours of sleep, and stress, exert varying influences. Consequently, it is necessary that, blood glucose should be analyzed in each training session, and necessary actions should be taken.

At times, it will be necessary to adapt the training to the expected behavior of blood glucose. For example, if a patient with T1DM has forgotten to lower the pre-training insulin dose and aerobic exercise was planned, it will be necessary to modify the training to high-intensity interval work to compensate for the drop in blood glucose that would have occurred with aerobic exercise. On the other hand, if insulin adjustment has not occurred or the patient is at high blood glucose values without circulating insulin, intense resistance training or HIIT should be substituted by aerobic tasks. General recommendations for practical application are shown in Table 2.

Table 2 Practical recommendations for exercise prescription in type 1diabetes mellitus patients

A patient’s previous experience and training status must be considered when designing any training program. In the first training weeks, the program should focus on basic general conditioning to improve technique in basic resistance exercises, such as squats, lunges, deadlift, and other press and pull movements. The first adaptations to resistance training are acquired with simple exercises (e.g., weightstack machines or exercises performed with simple materials such as elastic bands). Simultaneously, HIIT performed with low-impact exercises, such as cycling or rowing, is an excellent option since this does not require significant insulin-CHO adjustments and is safe for the lower limb joints. It is essential that the person increases daily activities (e.g., taking the stairs, walking as much as possible, reducing sitting time). Moreover, before each training session, a warm-up consisting of unloaded pedaling or cranking, general joint mobility, and dynamic stretching should be performed. Controlling daily load by quantifying the total training session rating of perceived exertion as well as glycemia levels before each session is recommended.

The ideal scenario would involve the use of continuous glucose monitoring, a relatively new technology that provides real-time knowledge of intra-session and inter-session glucose regulation[54]. Since glucose does not have a mathematical behavior, this technology is of great importance to prevent adverse events during exercise training and in the subsequent hours. In the same way, insulin pumps help to automatically regulate the exogenous administration of this hormone and maintain stable glucose levels, depending on exercise and diet. However, accessibility to continuous glucose monitoring is limited in real scenarios. Hence, it is important to analyze hormonal and metabolic responses to each type of exercise in patients with T1DM to control pre- and post-exercise insulin administration as well as CHO intake.

CONCLUSION

Aerobic and resistance exercise are safe and effective training methods in T1DM patients. Current evidence has shown that a supervised and individualized exercise program with aerobic exercise performed 1-3 times/week, including low-volume high-intensity exercise training along with 1-3 sessions per week of resistance training, is sufficient to improve physical fitness, functional capacity, quality of life, and mental health in this population. These guidelines should be adapted according to the patient’s needs, abilities, and preferences.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Professor Kazunori “Ken” Nosaka and Dr. James Nuzzo for their assistance in reviewing the manuscript during our stay in Edith Cowan University (July to October 2022).

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Martin-Rivera F, Maroto-Izquierdo S, García-López D, and Alarcón-Gómez J wrote and reviewed the paper.

Conflict-of-interest statement:The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:Spain

ORCID number:Fernando Martin-Rivera 0000-0003-1996-8276; Sergio Maroto-Izquierdo 0000-0002-6696-5636; David García-López 0000-0002-0079-3085; Jesús Alarcón-Gómez 0000-0003-0903-1295.

S-Editor:Chen YL

L-Editor:Filipodia

P-Editor:Chen YX

World Journal of Diabetes2023年5期

World Journal of Diabetes2023年5期

- World Journal of Diabetes的其它文章

- Early diabetic kidney disease: Focus on the glycocalyx

- Inter-relationships between gastric emptying and glycaemia:Implications for clinical practice

- Cardiometabolic effects of breastfeeding on infants of diabetic mothers

- Efficacy of multigrain supplementation in type 2 diabetes mellitus: A pilot study protocol for a randomized intervention trial

- Association of bone turnover biomarkers with severe intracranial and extracranial artery stenosis in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients

- Association between metformin and vitamin B12 deficiency in patients with type 2 diabetes