What, why and how to monitor blood glucose in critically ill patients

Deven Juneja, Desh Deepak, Prashant Nasa

Deven Juneja, Institute of Critical Care Medicine, Max Super Speciality Hospital, Saket, New Delhi 110017, India

Desh Deepak, Department of Critical Care, King's College Hospital, Dubai 340901, United Arab Emirates

Prashant Nasa, Department of Critical Care, NMC Speciality Hospital, Dubai 7832, United Arab Emirates

Prashant Nasa, Department of Critical Care, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Al Ain 15551, United Arab Emirates

Abstract Critically ill patients are prone to high glycemic variations irrespective of their diabetes status. This mandates frequent blood glucose (BG) monitoring and regulation of insulin therapy. Even though the most commonly employed capillary BG monitoring is convenient and rapid, it is inaccurate and prone to high bias, overestimating BG levels in critically ill patients. The targets for BG levels have also varied in the past few years ranging from tight glucose control to a more liberal approach. Each of these has its own fallacies, while tight control increases risk of hypoglycemia, liberal BG targets make the patients prone to hyperglycemia. Moreover, the recent evidence suggests that BG indices, such as glycemic variability and time in target range, may also affect patient outcomes. In this review, we highlight the nuances associated with BG monitoring, including the various indices required to be monitored, BG targets and recent advances in BG monitoring in critically ill patients.

Key Words: Blood glucose; Continuous glucose monitoring; Critical care; Glycaemic indices; Hypoglycaemia; Intensive care unit

INTRODUCTION

Blood glucose (BG) monitoring is a vital component of critical care management. Diabetes is an important risk factor for developing severe disease necessitating intensive care unit (ICU) admission. Additionally, any acute illness may increase the risk of derangement of BG levels. These fluctuations may happen irrespective of the diabetes status of the patient and may affect their ICU course and outcomes. Several factors have been identified that increase the risk of developing hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia in ICU patients (Table 1)[1-5]. The use of multiple medications, underlying comorbidities and organ dysfunctions, and rapidly changing patient conditions make BG control challenging in critically ill patients. Even the commonly used capillary blood sampling for BG monitoring may be unreliable in these patients[6].

Furthermore, glycemic indices and targets for optimizing outcomes in critically ill patients need to be clarified. Targeting tight glucose control, which was earlier recommended, has not shown any mortality benefit but may increase the risk of hypoglycemia by five times[7]. It also requires frequent blood sampling and regulation of insulin dose, which may increase the workload of healthcare workers and add to the cost of care. Hence, recent guidelines recommend more liberal BG targets to avoid the risk of hypoglycemia[8,9]. In addition to the commonly employed indices such as hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia, glycemic variability (GV) and time in target range (TITR) are recently recognized components of dysglycemia which may affect patient outcomes[10-12]. However, the exact targets for these indices still need to be well established.

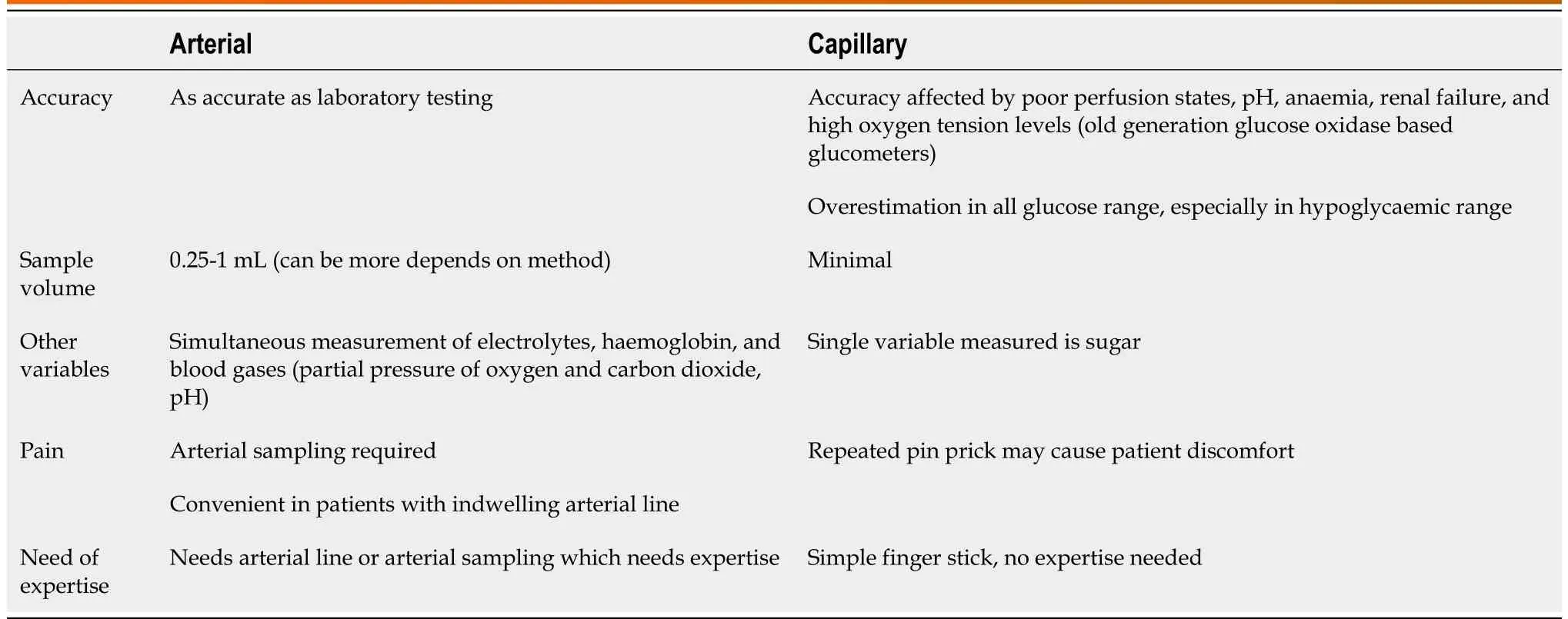

ARTERIAL VS CAPILLARY MONITORING

BG management requires frequent blood sampling and insulin dose adjustment. BG monitoring in critically ill patients by plasma-based central laboratory methods using venous or arterial samples is considered standard. However, due to the long turnaround time and convenience associated with a point of care testing (POCT), currently, glucometers and arterial blood gas (ABG) analyses are being frequently used. Bedside capillary blood glucose monitoring arguably remains the most commonly employed method, even in critically ill patients. However, its accuracy may be affected in patients with subcutaneous oedema, shock, and hypoxemia, which commonly affect ICU patients[4]. This may lead to highly variable results and higher bias (overestimation) for fingerstick sampling than arterial or venous BG monitoring, which can significantly affect clinical decision-making[13]. Hence, arterial blood is preferred but requires repeated arterial punctures or an invasive arterial line (Table 2). The correlation between arterial and capillary glucose levels is also significantly affected in patients with shock requiring vasopressors, with a proportion of disagreement ranging from 1.4% to 27.1%[14,15].

Table 1 Risk factors for developing hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia in intensive care unit patients

Table 2 Comparison between arterial and capillary monitoring of glucose

Over the years, there has been remarkable progress in the technologies used for bedside glucometers. Based on the glucose oxidase method, the initial generation of glucometers was affected by low and high haematocrit, blood pH, and even some medications[16]. The more recent glucose dehydrogenasebased glucometers are largely unaffected by high PaO2and other interferences but had a serious flaw of being highly inaccurate in patients on peritoneal dialysis whose dialysate contains Icodextrin, because of its hydrolysis to maltose, causing pseudo-hyperglycemia[17]. The accuracy and precision of the newer generation of glucometers have improved significantly. They have largely overcome the fallacies of their predecessors to acceptable clinical levels, especially if arterial or venous blood is used for analysis. Recent data suggest that these devices may achieve more than 97% correlation with the reference standard when testing venous and arterial samples. These systems have demonstrated acceptable clinical performance with high specificity, sensitivity, and low risk of potential insulindosing errors[18].

It can be inferred that arterial blood should be preferred over capillary blood for glucose monitoring, irrespective of the method used, provided standards of calibration are being followed. Although capillary glucose serves well in hospitalized patients, caution should be exercised in patients with shock[14], insulin infusion[15], on vasopressors[14,19], coma[20], and other critically ill adult patients[6]. A large meta-analysis with 21 studies showed that BG readings taken from arterial samples were significantly more accurate than those taken from the capillary samples. Again, as compared to glucometer readings, readings taken from ABG analyzers were more accurate, especially in the hypoglycemic range[6]. Despite venous samples tested in the laboratory remain the gold standard, POCT using arterial samples analyzed using ABG analyzers may provide an accurate estimation of the BG levels with the advantage of rapid turnaround time and may provide more clinically relevant and actionable information.

CONTINUOUS GLUCOSE MONITORING

Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) devices have evolved from retrospective analyzers validated in outpatient services and can now be utilized in hospitalized patients to optimize glucose control. These devices have been associated with better control of short-time fluctuations in BG levels, reduced glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) values, reduced risk of severe hypoglycemia, improved glycemic control, increased treatment satisfaction, and may also reduce healthcare costs[21,22]. Numerous CGM devices are commercially available, which are approved for in-hospital use. These devices are classified as noninvasive (transdermal), minimally invasive (subcutaneous) and invasive (intra-vascular).

The real-time analyzers have a subcutaneous cannula with a biosensor to analyze glucose from interstitial fluid, which is then relayed wirelessly by the attached transmitter to the monitors[23]. Even though the initial trials with CGM devices showed a reduction in hypoglycemic events as compared to the intensive insulin protocols measuring glucose samples frequently, these devices failed to reduce the GV[24,25].

The newer systems have shown a fair correlation in direct comparison with each other and capillary measurements in non-critically ill diabetic patients[26]. However, the data from critically ill patients, was lacking so far. Early results from testing in critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) have been encouraging, and these devices have been shown to have good accuracy, increase TITR, and reduce GV[27,28]. The latest generation of continuous subcutaneous flash glucose monitoring system (FreeStyle Libre) has been shown to have high test-retest reliability and acceptable accuracy even in critically ill patients[29,30].

Although evidence is still evolving, some drawbacks exist (Table 3). There is usually a time lag between blood and interstitial fluid to equilibrate, which hinders accurate real-time sampling[31]. Other issues which are worth considering are variable biosensor life, need for frequent calibration, and limited working range (BG levels between 40 and 400 mg/dL). Their efficacy has still not been evaluated in patients with severe oedema due to hypoalbuminemia and hepatic failure, in whom the correlation between blood and interstitial fluid might be altered and inaccurate[23]. Additionally, the presence of hypoxemia and shock may also affect their accuracy.

These shortcomings can be overcome by using intravenous CGM systems, which are more accurate, making frequent monitoring possible in critical patients without putting extra-time load on nursing staff. In addition, these devices can also be integrated with closed-loop systems providing an automated insulin delivery to improve BG management[32]. However, their application is also associated with a high incidence of sensor failure, loss of venous integrity, and logistic issues[33]. In addition, finding a suitable vein may also be an issue in critically ill patients[34].

The evidence supporting the clinical effectiveness and efficiency of these systems in ICU patients is still limited. Their impact on clinically relevant outcomes like ICU mortality, length of stay (LOS) in hospital and ICU remains unknown[35]. Moreover, validation of these systems in various ICU populations may lead to their widespread use, considering the advantages of avoiding hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia, and GV and reducing nursing loads with less need for finger pricks. Even though these devices may not be beneficial to all critically ill patients, they may benefit some specific ICU patients such as those on intravenous insulin or corticosteroids, and patients with end-stage organ dysfunction (renal or liver), post-operative neurosurgery or those with traumatic brain injury and post-organ transplant[36-38]. CGM is effective and safe in critically ill COVID-19 patients and may significantly reduce the need for bedside BG testing; thus, it is recommended to use CGM in these patients to reduce nursing exposure[39].

GLYCAEMIC INDICES

Traditionally glycemic control has been defined as highest and lowest target BG levels with an aim to prevent episodes of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia. In recent years, studies have evaluated other aspects to dysglycemia and their association with clinical outcomes in critically ill patients. Variability of these indices is a predictor of worse patient outcomes, independent of frequency and severity of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia[40,41]. Even though the current glycemic management guidelines do not recommend any specific target for many of these indices, based on the current data some suggestions may be made to optimize glycemic control in critically ill patients (Table 4)[8,41-45].

Table 3 Advantages and disadvantages of continuous glucose monitoring

Table 4 Suggested targets for various glycemic indices in critically ill patients

BG targets

Safe BG levels have been challenging to define in critically ill patients. Till recent years glucose control in ICUs has swayed between tight glycemic control (avoiding hyperglycemia) to liberal glucose control (avoiding hypoglycemia) in different case mix populations[46,47].

The American Diabetes Association recommends that a BG level below 180 mg/dL is acceptable for ICU patients[8]. In patients with sepsis, the recent version of surviving sepsis guidelines recommend targeting BG levels between 140 and 180 mg/dL and initiating intravenous insulin therapy if BG levels are above 180 mg/dL for two consecutive readings[9]. They further recommend measuring BG levels every 1-2 h, especially in the first 24 h after admission.

GV

The GV can be defined as the measurement of fluctuations of BG over a given interval of variable time. Markers of GV like standard deviation, coefficient of variation, mean amplitude of glycemic excursion, and one time-weighted index, the glycemic lability index (GLI), are significantly associated with higher risk of infections and mortality in medical-surgical ICU patients, even though the mean BG failed to show any association. Additionally, the patients in the upper quartile of GLI had the strongest association with infections [odds ratio (OR): 5.044,P= 0.004][41]. Even after correcting for hypoglycemia, GV has been reported to be an independent predictor of worse patient outcomes. In fact, GV has been shown to be a precursor of hypoglycemia, as the risk of hypoglycemia is 3.2 times higher in patients with increased GV[48].

TITR

TITR is the percentage of time where the BG stays in the pre-defined glycemic range, calculated per patient per day and expressed as a percentage of time spent. Glucontrol was one of the earliest randomized control trials (RCT) to show that TITR above 50% was independently associated with improved survival rates in critically ill patients irrespective of whether tight (80-110 mg/dL) or liberal (140-180 mg/dL) glycemic control was applied[49].

In another study, when three thresholds of TITR of 30%, 50%, and 70% were compared in 784 medical surgical patients, it was reported that there was significantly reduced organ failure with TITR of 50%. Additionally, a TITR above 70% further resulted in significantly improved survival rates[42]. Similarly, improved outcomes in terms of reduced sternal wound infection and LOS on invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) and in ICU has been reported in cardiac surgery patients who could achieve TITR above 80%[22]. The exact cut-offs remain to be defined as different studies have suggested TITR from 50%-80% to improve patient outcomes[22,42].

Glycemic gap

Glycemic gap is calculated by subtracting HbA1C-derived average glucose = [(28.7 × HbA1c) - 46.7] from plasma glucose at admission. In a cohort of 200 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus admitted to ICUs, the glycemic gap was found to be a predictor of multi-organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS), acute respiratory distress syndrome, shock, upper gastrointestinal bleeding, and acute renal failure (ARF). A glycemic gap of 25.89 mg/dL was predictive for the combined occurrence of mortality, MODS, and ARF[43]. Similarly, in a retrospective analysis of patients with community-acquired pneumonia, an elevated glycemic gap of 40 mg/dL had an OR of 3.84 for the incidence of a composite of adverse outcomes, which included length of IMV, and LOS in the ICU and hospital[50].

Glycemic lability

A glycemic lability (GL) is a measure of GV which records the change in glucose level over weeks calculated from all recorded glucose values. In a multicentric study, where GL and time-weighted average BG were calculated and analyzed, compared to patients with GLI below median 40 (mmol/L2/h/week), patients with GLI above this median had a significantly longer ICU stay and a higher ICU and hospital mortality. There was no significant association between GLI and mortality when comparing patients with and without diabetes and baseline HbA1c values. It was found that high GV, as determined by the GLI, was associated with increased hospital mortality independent of average BG, age, diabetes status, HbA1c, hypoglycemia, and illness severity[44].

Stress hyperglycemia ratio

Stress hyperglycemia ratio (SHR) is defined as the ratio of plasma glucose to average glucose derived by HbA1C [(1.59 × HbA1c) - 2.59], where HbA1c is used to estimate average glucose concentration over the prior three months. It accounts for acute stress-induced hyperglycemia and long-standing glycemic control. GLI and SHR are indices which account for premorbid glycemic control. Preliminary reports suggest that SHR may be a better marker of patient outcomes than hyperglycemia[51]. In specific patient populations, SHR has been shown to be a predictor of hemorrhagic conversion in acute ischemic stroke and poor outcomes in acute coronary syndrome[52,53]. In diabetic patients with sepsis, a high SHR (≥ 1.14) has been shown to be predictive of mortality[45]. While the exact cut-off value for SHR remains unclear, different SHR definitions have been used in the literature[54].

SHR1 = fasting glucose (mmol/L)/glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) (%)

SHR2 = fasting glucose (mmol/L)/[(1.59 × HbA1c) - 2.59]

SHR3 = admission BG (mmol/L)/[(1.59 × HbA1c) - 2.59]

SHR1 and SHR2 have been shown to be independently associated with worse clinical outcomes in patients with ischemic stroke after intravenous thrombolysis. Furthermore, SHR1 has been shown to have a better predictive performance for outcomes as compared to other SHR definitions[54].

Diabetic status and glycemic targets

The effect of acute and chronic hyperglycemia on modifying glycemic targets to optimize glycemic control in critically ill patients is yet to be studied in detail. The results from a study by Krinsley and Preiser[55] suggested that TITR greater than 80% for a BG target between 70 and 140 mg/dL was strongly associated with increased survival in critically ill patients without diabetes mellitus. However, such a relationship was not found in diabetic patients[55]. Lanspaet al[56] also reported that a TITR greater than 80% was associated with reduced mortality in non-diabetic patients and in those with wellcontrolled premorbid diabetes (judged by admission HbA1c). However, no such association could be shown in patients with poorly controlled diabetes[56].

In another study, a lower hospital mortality rate was observed in patients with higher (> 7%) preadmission levels of HbA1c and higher time-weighted average glucose concentration in critically ill patients. This suggests that patients with chronic hyperglycemia may benefit from more liberal glucose control and may tolerate a higher BG level[57]. However, such claims need to be better evaluated in large-scale trials before they are applied in routine clinical practice.

ROLE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

Artificial intelligence (AI)-based applications and devices have been in clinical use to manage noncritically ill diabetic patients for a long time. These devices have been used in patient-centered care to make an early diagnosis, predict complications, and even engage patients to ensure treatment adherence. There has been a heightened interest in AI applications for critically ill patients in the last few years. Even though there is insufficient evidence for its routine use, AI is increasingly utilized and can potentially change the future of critical care glucose management (Table 5)[58].

Table 5 Possible critical care applications of artificial intelligence in diabetes management

In ICU, frequent blood sampling and insulin dose adjustments are required to maintain glycemic control, increasing nursing workload and chances of error. AI has the potential to improve glycemic control while reducing nursing workload and errors. The LOGIC-1 and LOGIC-2 RCTs showed that software-guided algorithms could achieve better glycemic control than nurse-guided protocols without increasing the risk of hypoglycemia[59,60].

AI-based insulin bolus calculators and advisory systems like MD-Logic controllers are commercially available and have been shown to provide better glycemic control and reduce nocturnal hypoglycemic events[61]. Software-based algorithms have been used to regulate insulin infusion based on the patient’s glucose levels. Model predictive controls use algorithms based on patient parameters like their age and diabetes status, along with the dose of dextrose administered and the insulin sensitivity, which can predict the patient’s response to hyperglycemia and insulin therapy and adjust the insulin dose accordingly. These algorithms can improve the accuracy of predicting hyperglycemia, reduce the need for repeated blood sampling, and provide highly individualized insulin therapy[62,63].

CGM devices (Dexcom G6™) have been integrated with automated insulin suspension using AI algorithms (Basal-IQ™ technology). AI-based algorithms can predict when the BG levels may fall below the predefined levels and can alter the insulin infusion accordingly[64]. These CGM regulated insulin infusion systems have been shown to reduce the episodes of hypoglycemia effectively[65].

AI-based artificial pancreas (AP) has been shown to provide comprehensive glycemic control by effectively controlling BG levels, reducing wide glucose excursions, reducing episodes of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia, and increasing the percentage of TITR. Even in critically ill patients, AP achieved stable glucose control and reduced GV while reducing the episodes of hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia and the need for frequent sampling, thereby reducing the nursing workload[66-68]. Whether the use of AP can improve clinical outcomes and has a favorable cost-benefit ratio, still needs to be evaluated.

In addition to predicting long-term or chronic complications, AI may also be instrumental in predicting acute life-threatening complications like acute myocardial infarction in patients with diabetes[69]. AI using a convolutional neural network has been shown to be highly accurate in predicting mortality in critically ill diabetes patients with an area under the curve of 0.97[70,71]. However, these models need to be compared to more widely used and validated models for mortality prediction in ICU patients.

AI applications may improve patient care and outcomes and improve glycemic control while reducing nursing workload. As AI-based devices may enable us to monitor and institute therapy remotely, they may be particularly useful in managing highly infectious diseases like COVID-19. However, AI is still in the early stages of development and AI-based applications still need to be thoroughly evaluated and validated in critically ill patients. In addition, the need for more regulations, recommendations, and guidelines for using AI limit its applicability. Safety, liability, and reliability issues pertaining to AI application need to be better assessed before it is integrated into the existing healthcare infrastructure and becomes acceptable at a larger scale.

CONCLUSION

ICU patients are a unique population with dynamic clinical conditions and therapeutic needs. High physiological stress, raised inflammatory cytokines, varying nutritional intake, and fluctuating organ functions make glycemic control challenging in these patients. Guidelines may aid us in providing a generalized approach to glycemic control, but there may be a need for a more personalized approach to reducing the harmful effects of dysglycemia. The newer glycemic indices like GV and TITR may allow us to achieve patient-centered care with better glycemic control. However, their exact targets and impact on patient outcomes need to be better evaluated before they are routinely recommended. The use of AIbased applications may provide a more comprehensive solution in the future, but presently close monitoring and early detection and management of complications constitute the mainstay of glucose management.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Juneja D and Deepak D performed the majority of the writing, prepared the tables and performed data accusation; Nasa P provided the input in writing the paper and reviewed the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest statement:All the authors report no relevant conflicts of interest for this article.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:India

ORCID number:Deven Juneja 0000-0002-8841-5678; Desh Deepak 0000-0002-1654-9765; Prashant Nasa 0000-0003-1948-4060.

S-Editor:Fan JR

L-Editor:Ma JY

P-Editor:Fan JR

World Journal of Diabetes2023年5期

World Journal of Diabetes2023年5期

- World Journal of Diabetes的其它文章

- Early diabetic kidney disease: Focus on the glycocalyx

- Inter-relationships between gastric emptying and glycaemia:Implications for clinical practice

- Cardiometabolic effects of breastfeeding on infants of diabetic mothers

- Efficacy of multigrain supplementation in type 2 diabetes mellitus: A pilot study protocol for a randomized intervention trial

- Association of bone turnover biomarkers with severe intracranial and extracranial artery stenosis in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients

- Association between metformin and vitamin B12 deficiency in patients with type 2 diabetes