Mechanism of immune attack in the progression of obesity-related type 2 diabetes

Hua-Wei Wang, Jun Tang, Li Sun, Zhen Li, Ming Deng, Zhe Dai

Hua-Wei Wang, Jun Tang, Li Sun, Zhe Dai, Department of Endocrinology, Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University, Wuhan 430071, Hubei Province, China

Zhen Li, Department of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery, Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University, Wuhan 430071, Hubei Province, China

Ming Deng, Department of Radiology, Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University, Wuhan 430071, Hubei Province, China

Abstract Obesity and overweight are widespread issues in adults, children, and adolescents globally, and have caused a noticeable rise in obesity-related complications such as type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Chronic low-grade inflammation is an important promotor of the pathogenesis of obesity-related T2DM. This proinflammatory activation occurs in multiple organs and tissues. Immune cellmediated systemic attack is considered to contribute strongly to impaired insulin secretion, insulin resistance, and other metabolic disorders. This review focused on highlighting recent advances and underlying mechanisms of immune cell infiltration and inflammatory responses in the gut, islet, and insulin-targeting organs (adipose tissue, liver, skeletal muscle) in obesity-related T2DM. There is current evidence that both the innate and adaptive immune systems contribute to the development of obesity and T2DM.

Key Words: Type 2 diabetes mellitus; Obesity; Insulin resistance; Immune cells; Inflammation; Pathological mechanism

INTRODUCTION

Globally, obesity and associated complications are widespread. Over the past 40 years, the impact of this non-contagious disease has spread from high-income countries to low- and middle-income countries, with its prevalence nearly tripling globally. Statistics from the World Health Organization in 2016 showed that 13% of the global adult population is obese, and more than 1.9 billion adults are overweight. The prevalence and degree of overweight and obese children and adolescents have also noticeably risen, generating concern for future years. Up to 2025, it is estimated that about 20% of the global population will be obese[1,2]. Widespread obesity among adults and adolescents will lead to a striking increase in obesity-driven health complications such as type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), as most T2DM patients tend to be overweight or obese[3,4].

The close correlation of obesity with T2DM has generated broad research interests of researchers. Although the pathophysiological mechanisms linking obesity to T2DM remain unclear, many studies have suggested that immune attack induced by overnutrition in multiple organs strongly contributes to insulin resistance (IR), lipotoxicity, and glucotoxicity. In this review, we examine recent advances and underlying mechanisms of local and systemic immune attack and chronic low-grade inflammation in T2DM induced by obesity.

IMMUNE ATTACK IN THE GUT OF OBESITY-RELATED T2DM

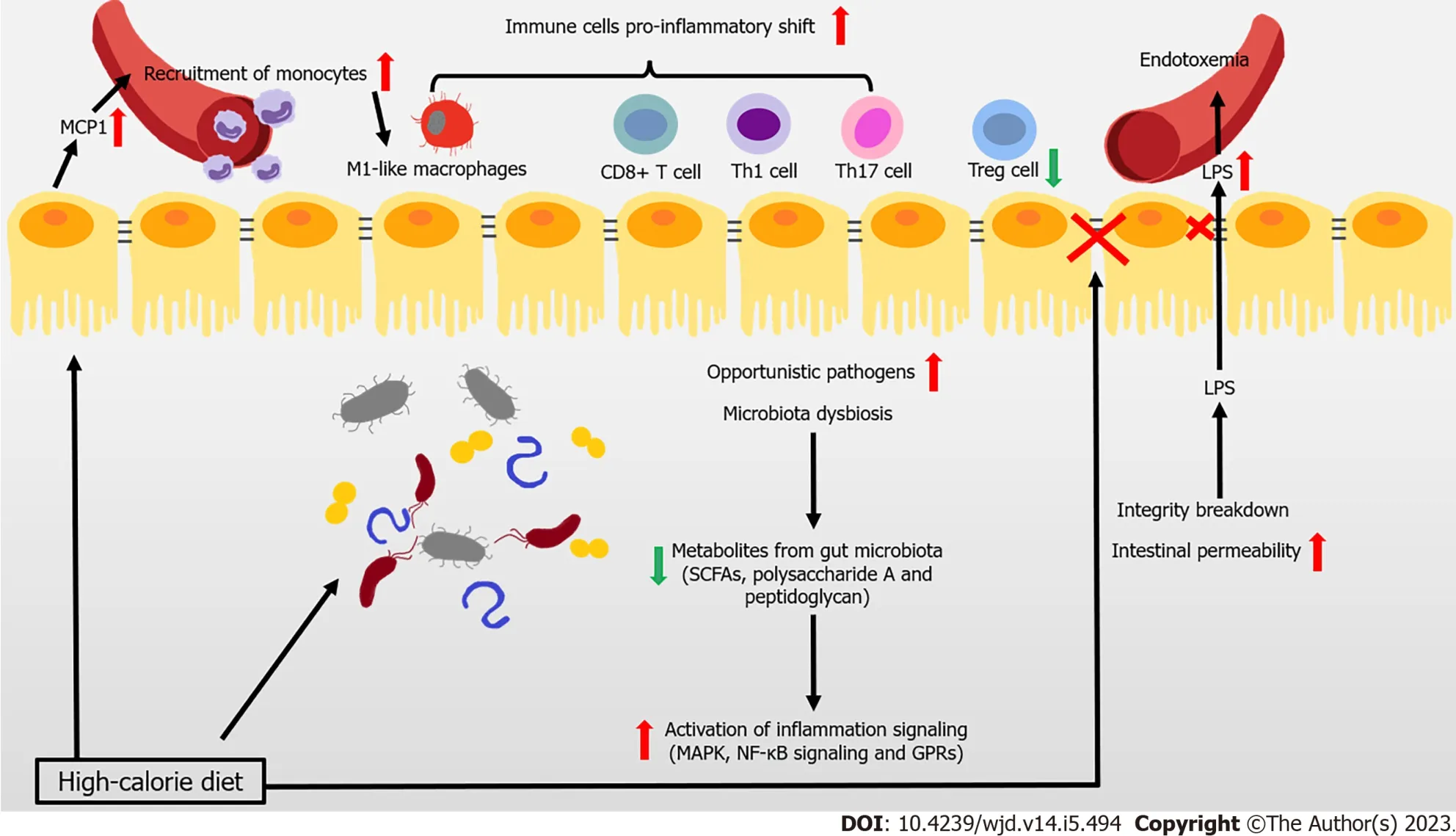

Most patients with T2DM are obese or overweight. These two states represent the disrupted condition of energy homeostasis in the body, due to chronic excessive calorie intake over expenditure. The gut is the first important “station” through which high-calorie food enters the body. There is recent widespread evidence that disturbance to the gut (particularly the dysbiosis of gut microbiota, imbalance of immune cells, and impaired gut barrier function) hinders the immune response and contributes to the development of obesity related IR and T2DM (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Immune attack and inflammation in the gut during obesity-related type 2 diabetes.

The composition of gut microbiota is complex, with high variability across individuals. This composition can be altered by changes to diet, and is closely associated with the development of disease. Reduced gene richness of gut microbiota is a common phenomenon caused by modern dietary structure, and might be associated with dyslipidemia, severe IR, and low-grade local or systemic inflammation[5,6]. Existing studies have shown that after introducing microbiota from obese donors to germfree mice, lipid accumulation and IR arose. This result demonstrated the close association between the gut microbiota and metabolic disorders in obesity-related T2DM[7,8]. Changes to metabolites caused by an altered gut microbiome help mediate the link between the host and gut microbiome. Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) are the products of undigested dietary fibers degraded by gut bacteria, and include acetate, propionate, and butyrate. These SCFAs have anti-inflammatory properties, in particular, butyrate[9,10]. Metagenome-wide studies have shown that the dysbiosis of gut bacteria occurs in patients with T2DM, in which the abundance of butyrate-producing bacteria declines, while that of opportunistic pathogens increases[11,12]. For instance, the administration of commercialBifidobacteriumstrains reduces body weight gain and downregulates inflammation, by reshaping intestinal gene signatures in mice[13]. Many studies have shown that the anti-inflammatory effects of butyrate are mainly achieved by inhibiting mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) in intestinal epithelial cells, which reduce the secretion of proinflammatory mediators and molecules involved in the homing of inflammatory cells[14]. The metabolite-sensitive G protein-coupled receptor (GPR) and its ligands strongly affect anti-inflammatory responses, with SCFA functioning being partially mediated by their receptors GPR41 and GPR43[15-17]. In addition to SCFAs, bacteria from the phylumBacteroidetesproduce glycan from fiber modulating immune function to protect against inflammation, such as polysaccharide A and peptidoglycan[18]. Thus, the anti-inflammatory responses involving SCFAs and other microbial-related metabolites in the intestine are likely weakened in the gut, and are likely closely associated with the development of obesity and T2DM.

The infiltration and proinflammatory shift of immune cells contribute to the inflammation of the intestine under metabolic challenge. In mice and obese humans, high-fat diet (HFD) induces chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2/monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (CCL2/MCP-1) production to rise in epithelial cells, which recruit monocytes to the gut, shifting to the proinflammatory phenotype[19,20]. Macrophage-specific deletion of C-C chemokine receptor type 2 (CCR2) ameliorates insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance, confirming the association between the infiltration of proinflammatory macrophages and obesity-induced metabolic disorders[19]. Moreover, HFD also induces a proinflammatory shift in T cells, with elevated interferon gamma (IFN-γ)-producing CD4+, CD8+ T cells, and interleukin 17 (IL-17)-producing γδ T cells, along with decreased regulatory T cells (Tregs)[21]. Tregs are one lineage of CD4+ T cells. These cells are involved in maintaining immune homeostasis and restricting excessive immune responses. T helper 17 (Th17) cells might secrete IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-21, and IL-22. Several strains ofClostridiahelp with the expansion and differentiation of Tregs, by providing bacterial antigens and an environment rich in transforming growth factor beta, contributing to the immunological homeostasis of the gut[22,23].Lactobacillus reuteri, Bacteroides fragilis,B. hetaiotaomicron,Clostridium, andFaecalibacterium prausnitziipromote the differentiation of Tregs. Segmented filamentous bacteria are required for Th17 cells to develop in the gut. Furthermore, SCFAs improve the Treg/Th17 balance, and induce IL-22 production in CD4+ T cells and innate lymphoid cells (ILCs), maintaining intestinal homeostasis[17,24,25].

Many studies have shown that serum lipopolysaccharide (LPS) levels rise in T2DM patients, with a triggering factor to IR and diabetes being identified that is closely associated with intestinal integrity and permeability[26,27]. One recent study of 128 obese human subjects showed that the abundance ofEscherichia coli, an important producer of LPS, was higher in obese patients with T2DM compared with the lean patients[28]. LPS is recognized by Toll-like receptors (TLRs) of the innate immune system, leading to the aggregation of macrophages and activation of the NF-κB inflammatory signaling pathway. This process triggers systemic immune and inflammatory responses that aggravate IR[14,29]. In general, a healthy intestinal barrier protects the organism from the passage of microbes. However, the intestinal barrier of people with T2DM is disturbed, leading to the uncontrolled passage of LPS and microbiota-derived molecules, and subsequent endotoxemia and chronic inflammation[30]. In particular, obese mice have fewer immunoglobulin A (IgA)-secreting immune cells and lower IgA secretion and glucose metabolism disorders arise in obese IgA-deficient mice. Administering metformin and bariatric surgery augment cellular and stool IgA levels[31]. Obese patients with T2DM exhibit a lower expression of intestinal tight junction genes and interference with the WNT/B-catenin signaling pathway, both of which are linked increased intestinal epithelial and gut vascular permeability[31-33]. Several immune cells (such as mucosal-associated invariant T cells [MAIT]) also impair gut integrity by inducing the dysbiosis of microbiota[34]. IL-1B can increase barrier permeability in intestinal epithelial cells, whereas IL-22 is considered a protector of maintaining intestinal barrier integrity[35-37]. Reduced integrity and higher intestinal permeability of the intestine promote the translocation of microbiotaderived molecules from the intestinal lumen to the bloodstream. This process triggers the activation of lamina propria macrophages in the intestine, causing LPS levels to rise in the blood.

IMMUNE ATTACK IN THE ADIPOSE TISSUES OF OBESITY-RELATED T2DM

Eating more calorie-dense foods combined with less exercise promotes the development of obesity. In both mice and humans, excess energy is stored in white adipose tissues (ATs) (WAT), which serves as the immune and endocrine organ containing mature adipocytes, adipocyte precursor cells (also called adipose stromal cells), and immune cells. Obesity causes a persistent low-grade inflamed condition in these expanding adipose depots, and the simultaneous infiltration of immune cells in the stromal vascular fraction and systematic metabolic disorders. The inflammatory storm driven by dysfunctional WAT disrupts its normal function and that of other insulin-sensitive organs. Consequently, this process contributes to the pathophysiological mechanisms of IR and T2DM (Figure 2). However, in obese subjects with T2DM, this immune attack appears to be stronger. Obese patients with T2DM have a higher degree of inflammation at both the systemic and AT level compared to patients with normal glucose tolerance. This phenomenon is characterized by aggravated macrophage infiltration in WAT, with elevated IL-6 levels and CD4+ T cell numbers in serum[38].

Figure 2 Immune attack and inflammation in the white adipose tissue during obesity-related type 2 diabetes.

Macrophages are representative immune cells of the innate immune system, and were first studied in relation to the process of immune infiltration in WAT. The infiltration and activation of macrophages is beginning to be recognized as a pivotal instigator of meta-inflammation. Normally, M2 anti-inflammatory macrophages are the main type in WAT[39,40]. However, as obesity develops, instead of the M2-phenotype, M1 proinflammatory macrophages in AT gradually increase (up to 40% of cells in AT), leading to a proinflammatory state in WAT[40-42]. The greater increase in M1-like polarized macrophages results in their being responsible for almost all secretions of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) and IL-6 in WAT. In turn, this process impairs the insulin signaling pathway, leading to IR, both locally and systemically[43]. Initially, the proliferation of resident macrophages dominates the accumulation of macrophages in WAT. Then at the later stage of obesity, recruited monocytes con-tribute to the accumulation of macrophages, following the secretion of CCL2/MCP-1 and leukotriene B4 by adipocytes to the microenvironment[44-46]. Free fatty acids (FFAs) derived from the diet and triglyceride lipolysis in hypertrophied adipocytes also promote M1-like polarization through a TLR4-dependent mechanism in WAT. In turn, this process increases FFA levels by aggravating lipolysis, establishing a positive feedback loop between FFAs and TLR4 activation in WAT[47,48]. Moreover, microRNAs (miRNAs) are considered to be important links between adipocytes and macrophages. Adipocyte-derived miRNAs (such as miR-30, miR-34a, miR-21, and miR-10a-5p) regulate the immune balance between M1- and M2-macrophage polarization[49-52]. Besides, proinflammatory macrophages also facilitate neutrophil recruitment to metabolic tissues during obesity, by releasing nucleotides through pannexin-1[53].

Aside from macrophages, adaptive immune cells are involved in the pathogenesis of obesity-related T2DM. In HFD-induced obese mice, CD8+ T cells are recruited into AT, promoting M1-like polarization[40,54,55]. However, different categories of CD4+ T cells have various functions in AT[56]. Proinflammatory CD4+ T cells (Th1, Th17, and Th22) are important promoters of the development of obesityassociated metabolic disorders. These cells produce proinflammatory cytokines (IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-17, and IL-22), and are involved in the recruitment and activation of M1 macrophages[57-60]. MAIT are innate-like T cells that express a semi-invariant T cell receptor, which promote inflammation in AT by inducing M1 macrophage polarization. This process leads to IR and impaired glucose and lipid metabolism[34]. Conversely, Tregs provide an essential accessory function that prevents systemic metabolic disorders, through suppressing the expression of MCP-1 in adipocytes to limit M1 macrophage infiltrationviaIL-10 and other insulin-sensitizing factors. However, the development of Tregs in WAT seems to depend on insulin signaling. Insulin signaling drives the transition of CD73loST2 (IL-33 receptor)hiadipose Treg subsets, which might also suppress inflammation in WATviathe hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha-mediator complex subunit 23-peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma axis[61]. Furthermore, AT B cells also negatively control local inflammation by secreting IL-10 (secreted by Bregs) and other soluble factors. B cells also contribute to systemic inflammation by activating CD8+ and Th1 cells, and releasing pathogenic antibodies[62-65]. B cells from obese mice consistently produce a proinflammatory cytokine profile compared to those from lean controls[66]. B cells transferred from obese mice induce the development of IR in B cell-deficient lean mice. By contrast, B cell depletion in mice restores aberrant immune cell composition and improves metabolic capacity in WAT[67]. T-bet B cells are B cells lacking cluster of differentiation 21 (CD21) and CD23. These cells accumulate in humans that have an elevated body mass index, and in mice with higher body weight. Mice without T-bet B cells have lower weight gain and M1 macrophage infiltration in WAT[68,69]. Thus, regulation of the adaptive immune system is related to the inflammation of AT in obesity. Adaptive immune cells are involved in AT IR in obesity-related T2DM; however, some of these effects may be achieved through promoting the polarization of M1-like macrophages.

Recent studies have shown that other types of cells in AT also participate in regulating immune balance. Mesenchymal cells contribute towards shaping immune responses and maintaining immune homeostasis in WAT. Mesenchymal cells express IL-7, IL-33, and CCL19, which recruit both innate and adaptive lymphocytes. IL-33 is produced by particular mesenchymal stromal cells in visceral AT (VAT), IL-33 improves IR and inflammation in AT, possibly through expanding and sustaining the resident Treg population[70-73]. Administering IL-33 helps combat obesity, by markedly increasing the fraction of group 2 ILCs and eosinophil, and improving WAT browning[74].

However, the distribution of AT appears to be closely related to the occurrence and progression of metabolic diseases. It has been universally accepted that central body fat deposition and injured function of AT are closer associated with obesity-related metabolic diseases than fat mass in the whole body. Generally, AT is divided into abdominal subcutaneous AT, femoral subcutaneous AT (FSAT, main type of lower-body AT), VAT, according to their different location. SAT is the largest AT depot. The expansion of FSAT and adipocyte hyperplasia from precursor cells are considered to be a healthier alterative of AT in meeting elevated storage energy demands. However, any damage to these approaches leads to the accumulation of fat in upper body AT and organs, which causes “lipotoxicity” in other insulin-sensitive organs, as well as systemic IR and a higher risk of T2DM. Several studies have found that SAT may have a more beneficial metabolic phenotypes, notably its accumulation in lowerbody[75,76]. Upper body AT (especially VAT) is usually characterized by more rapid storage of energy and a higher lipolysis rate than lower-body, which contributes to systemic FFA levels[77]. Interestingly, a recent study revealed that expanded adipocytes, lower SAT oxygenation, inflammation infiltration in SAT, and elevated FFA release, these changes in SAT that were considered harmful, seemed to be unrelated to the occurrence of obesity-induced IR[76,78]. Collectively, expansion and inflammation in VAT, rather than SAT, are the culprit involved in obesity-related metabolic diseases. Therefore, the effects of abdominal WAT accumulation are of more concern.

INFLAMMATION AND IMMUNE STATUS IN METABOLICALLY HEALTHY OBESITY

Metabolically healthy obesity (MHO) is a subgroup of obesity, which does not have an universally accepted definition. In most studies, MHO presented without the following features: dyslipidemia, IR, impaired glucose metabolism, and overt T2DM. Compared with metabolically unhealthy obesity (MUO), MHO usually has more expandability of SAT, less ectopic fat accumulation, normal concentration of inflammatory markers, and preserved better B-cell function, and insulin sensitivity[79-81]. Systematically, decreased concentrations of C-reactive protein, TNF-α, IL-6, and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 were found in the MHO subjects than MUO individuals[82]. Changes to the distribution and function of AT might also strongly contribute to the conversion of these two states. Excess caloric storage demand leads to the overload of SAT and ectopic fat accumulation and this ectopic fat deposition will eventually cause the transition from MHO to MUO[79]. Besides, many studies have revealed that less immune cells infiltration (such as proinflammatory macrophages and T lymphocytes) and cytokines production in MHO than in MUO, usually along with the increased VAT mass[83-86]. Improved antioxidant capacity and diminished oxidative stress could be also observed in MHO subjects than in MUO people[87,88].

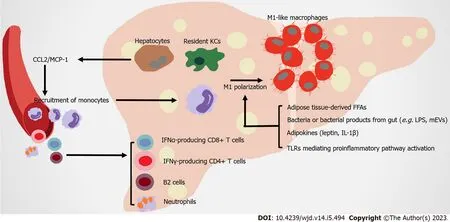

IMMUNE ATTACK IN THE LIVER OF OBESITY-RELATED T2DM

The liver is the metabolic center of nutrients and drugs in the body. It receives material supplied from the gutviathe portal vein, proinflammatory immune cells and cytokines from circulation, which strongly impact its physiological function (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Immune attack and inflammation in the liver in obesity-related type 2 diabetes.

Liver macrophages contribute to obesity-related hepatic IR by producing both inflammatory and noninflammatory factors. Hepatic macrophages include resident macrophages (Kupffer cells [KCs], high expression of F4/80 and C-type lectin domain family 4 member F) and recruited hepatic macrophages (RHMs), high expression of CD11b and CCR2. RHMs are derived from circulating Lyc6+ monocytes, which are recruited by steatosis hepatocytes and KCs secreting CCL2/MCP-1[89-92]. Although the ratio of KC to RHM is different in the liver of healthy mice and humans, as obesity develops, hepatic RHMs noticeably increase. These RHMs serve as a main promoter of inflammation injury in the liver, by producing chemokines and cytokines (in both humans and mice), which are related to obesity induced IR[93-95]. Multiple mechanisms are involved in the proinflammatory activation of hepatic macrophages. In obese individuals, FFAs overflow from obese AT contributes to the activation of resident hepatic macrophages[96]. Leptin and adiponectin from expanded AT have contrasting actions on KCs. The former stimulates proinflammatory and profibrogenic cytokines in KCs, whereas the latter modifies KCs towards anti-inflammatory phenotypes[97,98]. AT-derived proinflammatory cytokines (such as IL-1B) contribute to the chronic activation of hepatic NF-κB, promoting the development of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)[99]. KCs highly express scavenger, complement, and pattern recognition receptors, including TLRs. Intestinal permeability rises during obesity, leading to the translocation of bacteria or their products to the portal circulation. These substances are recognized by TLRs in macrophages, which activate NF-κB, IFN regulatory factors and other downstream transcriptional factors to induce inflammatory responses[100]. Microbe-related products, including extracellular vesicles (mEVs) containing gut microbial DNA, that leak from gut reach the liver, and exacerbate obesity-associated hepatic inflammation and IR. Vsig4+ macrophages and CRIg+ macrophages efficiently clear mEVs through a complementary component C3-dependent mechanism; however, HFD impairs these benefits[101,102]. CD68 serves as a marker for macrophages residing in the liver; however, this indicator is not sufficient for distinguishing them from monocyte-derived cells. The utilization of single-cell sequencing allows their origin, function, and associated inflammatory phenotype to be clearly distinguished. Two distinct populations of intrahepatic CD68 macrophages exist in human livers.CD68MARCO+++-cells are characterized by the enriched expression of LYZ, CSTA, and CD74, which represent their proinflammatory function. TheCD68MARCOmacrophage subset is similar to resident KCs, inducing immune tolerance[103]. Counter to expectation, KCs in diet-induced steatohepatitis probably participate in reparation pathways, not proinflammatory function[104]. However, KCs and RHMs both shift towards a proinflammatory phenotype[105]. Overall, the types and functions of liver macrophages are still under investigation.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), obesity, and T2DM are closely related in terms of pathogenesis. The prevalence of NAFLD is higher in subjects with obesity compared to lean subjects[106,107]. T2DM is also closely associated with NAFLD and its severe form NASH. Most T2DM patients suffer from NAFLD[108-110]. NAFLD, particularly NASH, usually leads to more severe hepatic IR that negatively affects T2DM development[111]. In NASH mice, KC is gradually replaced by RHM. Although RHM could respond to local environmental clues and develops a KC-like transcriptomic profile, this profile is not identical to original healthy KCs[90]. In healthy subjects, KCs inhibit monocyte and macrophage recruitment by secreting IL-10 and promoting immune tolerance through inducing Tregs and programmed death-ligand 1 expression. However, when NASH happens, injured hepatocytes activate KCs and recruit monocytes to the liver, and produce proinflammatory cytokines. Besides, these proinflammatory macrophages trigger the activation of hepatic stellate cells, leading to progression of the extracellular matrix and fibrosis in liver[112,113]. TLRs mediate the greater activation of the proinflammatory pathway as NASH progresses. Excess FFAs drive the endocytosis of a monomeric TLR4 complex, enhancing the generation of reactive oxygen species and causing steatohepatitis and IR[114]. TLR2 and TLR4 signaling activates inflammasomes (e.g.,pyrin domain-containing protein 3, NLRP3) in KCs, aggravating hepatic steatosis and NASH inflammation[115-117]. TLR9 is primarily confined to the endosomes of macrophages, which are activated by higher levels of mitochondrial DNA and oxidized DNA in liver, triggering NASH[118,119]. Conversely, inhibition of TLR2, TLR4, and TLR9 signaling pathways has anti-inflammatory effects, representing a potential treatment target for NASH[118,120].

The histopathology hallmarks of human NASH include the infiltration of neutrophils with MPOpositive immunoreactivity[99]. Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) are extracellular web-like structures of decondensed chromatin with cytosolic and granule proteins. These structures are important in hepatic chronic inflammatory conditions. NET blockade significantly decreases the infiltration of RHMs and neutrophils[121].

Moreover, recent studies have focused on elucidating the role of adaptive immunity cells in liver inflammation under metabolic challenge. The accumulation of B cells (especially B2 cells) and T cells in liver arises in more than half of NASH patients[122-124]. B cell-activating factor levels in the circulation are elevated in NASH patients compared to those with simple steatosis. This phenomenon is associated with more advanced IR, more severe steatohepatitis and fibrosis[123,125,126]. The contribution of B cells to the progression of NASH could be attributed to the production of proinflammatory mediators and their antigen-presenting capabilities[122]. Interfering with B2 cells reduces the Th1 cell activation of liver CD4+ T cells and IFN-γ production[123]. In both humans and mice, IFN-γ-producing CD4+ T cells and IFN-α-producing CD8+ T cells increase in the liver, promoting IR under diet-induced metabolic stress[127,128]. Thus, the infiltration of adaptive immunity cells in liver strongly affect inflammatory mechanisms during the development of NASH.

IMMUNE ATTACK IN THE ISLET OF OBESITY-RELATED T2DM

In the pathophysiologic process of islets of obesity and T2DM, innate immune cells are important, especially macrophages. Increased infiltration of resident macrophages and transformation towards a proinflammatory phenotype contributes to obesity and T2DM islets, the extent of which is generally correlated with B-cell dysfunction[129-131] (Figure 4). Islet macrophages express F4/80, CD11c, major histocompatibility complex class II, CD64, CD11b, CX3C motif chemokine receptor 1, CD68, and lysozyme[132]. At the early stage of obesity, resident macrophages enhance the compensatory proliferation of B cells, mediated by platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-PDGF receptor signaling[129]. As the disease progresses, CD68-positive macrophages are elevated in T2DM islets[130,133,134]. The proliferation of resident macrophages causes them to accumulate in islets with elevated inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (such as IL-1B, TNF-α), impairing the hyperplasia and dysfunction of B cells[131]. Overall, changes to the number and function of islet macrophages affect the pathogenesis of obesity and T2DM.

However, the factors that trigger the infiltration and proinflammation polarization of macrophages in islets remain unclear. B cells are potentially one of the early responders in the altered islet microenvironment. In obesity, B cells recruit Ly6C+ monocytes to the islets by producing chemokines, despite these recruited monocytes remaining at the boundary of the exocrine and endocrine pancreas[129]. Amyloid deposition in islets is a typical pathological feature of T2DM, and is also a strong stimulus for macrophage-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome activation and IL-1B production[135-137]. In amyloidpositive T2DM islets, the number of macrophages greatly increases, with CD68 and inducible nitric oxide synthase-positive[134]. Macrophages that are resident to islets act as heightened sensors of interstitial ATP levels. Consequently, glucose-activated insulin and ATP co-secretion of B cells might trigger cytokine production from macrophages[138]. Macrophages resident to islets are in contact with blood vessels, probably protecting against inflammatory moieties from blood by extending their filopodias; however, high concentrations of glucose in T2DM limit this method of capture[139,140]. In addition, GRP92 activation in islet macrophages promotes conversion to the anti-inflammatory phenotype, and improves B-cell function[141]. The accumulation of intestinal mEVs causes CD11c+ macrophages to increase, with elevated IL-1B in islets impairing insulin secretion. Vsig4+ macrophages in islets block intestine-derived mEVviaa C3-mediated mechanism. By contrast, obesity causes a marked decrease in Vsig4+ macrophages[142].

IL-1B is a key proinflammatory cytokine that clearly increases in T2DM islets. Although macrophages are considered to be the major producers of IL-1B in obesity islets, for which the potential mechanism has been identified, B cells also produce IL-1B[129,137]. Glucose-induced IL-1B auto-stimulation in B cells might contribute to glucotoxicity in T2DM islets[143,144]. However, IL-1B on B cells seem to have varied effects. For instance, low concentrations of IL-1B help to increase B-cell proliferation and improve insulin secretion following glucose stimulation. By contrast, high concentrations of IL-1B promote inflammation in islets, and might be closely related to the development of pre-diabetes and T2DM[145-147]. The IL-1R antagonist (IL-1Ra) also declines in T2DM B cells, pushing the IL-1/IL-1Ra balance towards a proinflammatory state[148-151]. The vaccine and responsive miRNA targeting IL1B are promising approaches for treating T2DM, by restoring B-cell mass, inhibiting B-cell apoptosis, and increasing insulin secretion[152-154]. Thus, antagonizing IL-1B is a potential target for T2DM treatment.

IMMUNE ATTACK IN THE SKELETAL MUSCLE OF OBESITY-RELATED T2DM

As skeletal muscle is the principle organ for glucose disposal, IR in this tissue becomes a crucial determinant of obesity and T2DM-related metabolic disorders[155,156]. Immune attack and inflammatory responses in skeletal muscle also regulate IR formation (Figure 5). CD11c-expressing proinflammatory macrophages, monocytes, and neutrophils are higher in the skeletal muscle of HFD-induced mice compared to the control[157,158]. More macrophages markers are found in the skeletal muscle of healthy subjects after HFD administration, with the development of IR[159,160]. In obese T2DM patients, the number of CD68+ macrophages is elevated in skeletal muscle[158,161]. Total T cells and αB T cells, containing CD8+ T cells and IFN-γ-producing CD4+ cells are higher in the skeletal muscle of obese mice compared to control mice[162]. FFAs induce or synergize with macrophages to aggravate the inflammatory response in muscle cells, resulting in IR[163-165]. These immune cells infiltrate skeletal muscle, and accumulate in muscle AT between myocytes and the surrounding muscle, leading to higher levels of local proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1B, and IFN-γ[158,160,166].

Figure 4 Immune attack and inflammation in the islet in obesity-related type 2 diabetes.

Figure 5 Immune attack and inflammation in the skeletal muscle in obesity-related type 2 diabetes.

Similar to adipocytes, skeletal muscle cells produce MCP-1, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, and other molecules, and part of these molecules lead to the infiltration of macrophages, inducing IR[157,167]. Muscle biopsies show that the gene expression of inflammatory cytokines (such as TNF-α) is upregulated in IR subjects[168]. Compared with non-diabetic subjects, more IL-6, IL-8, IL-15, TNF-α, growth related oncogene α, MCP-1, and follistatin are released by skeletal muscle cells from T2DM patients[169]. Aerobic exercise reduces the infiltration of macrophage in skeletal muscles, and improves insulin sensitivity and elevates the production of anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10[170]. IL-10 attenuates macrophage infiltration and cytokine response in skeletal muscle, mitigating diet-induced IR[160]. Interestingly, while IL-6 usually promotes inflammation, acute IL-6 treatment in skeletal muscle strengthens insulin-stimulated glucose disposal in humans, possibly mediated by AMP-activated protein kinase signaling[171,172]. Therefore, the exact role of myokines in the metabolism of skeletal muscle needs to be further clarified.

TLRs are also present in skeletal muscle. The expression and signaling of TLR4 is elevated in the muscle of IR patients[173]. LPS-induced IR in skeletal muscle entirely depends on TLR4[174]. The inhibition or deletion of TLR4 prevents acute hyperlipidemia-induced skeletal muscle IR[175,176]. Palmitate induces myeloid differentiation primary response 88 and TLR2 receptor to combine in mouse myotube cells, providing the foundation for inflammation and IR[177]. Therefore, TLRs are also involved in activating proinflammatory factors on skeletal muscle cells.

Overall, many studies support the association of obesity and related-T2DM with increased inflammation of skeletal muscle in rodents and humans. The greater infiltration of macrophages and T cells, and their polarization towards proinflammatory phenotypes, means they act as primary promoters in increasing the inflammation of skeletal muscle. Skeletal muscle cell-secreting myokines also exhibit proinflammatory effects during the development of obesity and T2DM.

CONCLUSION

Chronic low-grade inflammation involving the immune system is a typical feature of obesity-associated T2DM. It generates an inflammatory storm affecting multiple organs and tissues throughout the body. Adaptive activation of the immune system usually stems from an energy imbalance in the body induced by excess calorie intake. However, as the imbalance continues to grow, parenchymal cells and immune cells (in particular, macrophages/monocytes), and their cross-talk, promote the inflammatory response and the development of T2DM by exacerbating IR. Targeting immune cells and relative inflammatory responses is an effective treatment of obesity and associated T2DM.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Wang HW, Tang J, and Dai Z took part in the conception and wrote the review; Sun L, Li Z, and Deng M made intellectual contributions to the writing and revision of this review; Wang HW and Dai Z contributed to the design of figures and revised thoroughly the final version; Dai Z was responsible for supervision, manuscript writing and editing, and funding acquisition.

Supported bythe National Science Foundation of China, No. 81500593; and the Science and Technology Innovation Platform Project of Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University, No. PTXM2021016.

Conflict-of-interest statement:The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:China

ORCID number:Hua-Wei Wang 0000-0001-7534-2863; Jun Tang 0000-0002-6908-1027; Li Sun 0000-0001-5921-6664; Zhen Li 0000-0002-0464-1791; Ming Deng 0000-0003-4916-4877; Zhe Dai 0000-0003-0321-0225.

S-Editor:Zhang H

L-Editor:Filipodia

P-Editor:Yu HG

World Journal of Diabetes2023年5期

World Journal of Diabetes2023年5期

- World Journal of Diabetes的其它文章

- Early diabetic kidney disease: Focus on the glycocalyx

- Inter-relationships between gastric emptying and glycaemia:Implications for clinical practice

- Cardiometabolic effects of breastfeeding on infants of diabetic mothers

- Efficacy of multigrain supplementation in type 2 diabetes mellitus: A pilot study protocol for a randomized intervention trial

- Association of bone turnover biomarkers with severe intracranial and extracranial artery stenosis in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients

- Association between metformin and vitamin B12 deficiency in patients with type 2 diabetes