血清全氟化合物与代谢相关脂肪性肝病患病风险的关系

张露露,刘 婧,贺颖倩,赵亚楠,郑 山,王敏珍

血清全氟化合物与代谢相关脂肪性肝病患病风险的关系

张露露,刘 婧,贺颖倩,赵亚楠,郑 山,王敏珍*

(兰州大学公共卫生学院,流行病与卫生统计学研究所,甘肃 兰州 730000)

基于2017~2018年美国国家营养调查与健康调查数据集(NHANES),探究血清全氟化合物(PFAS)对代谢相关脂肪性肝病(MAFLD)的影响以及在不同人群中的效应差异.采用Logistic回归模型和限制性立方样条评估各污染物的效应和剂量反应关系.结果表明:单污染物模型发现血清全氟辛烷磺酸(PFOS)、全氟己烷磺酸(PFHxS)、全氟癸酸(PFDA)与MAFLD患病风险呈负向关联,OR值分别为0.64(95%CI:0.45~0.91)、0.65(95%CI:0.46~0.93)、0.45(95%CI:0.30~0.67);多污染物模型中,与最低四分位数浓度(Q1)相比,血清全氟壬酸(PFNA)浓度处于Q2、Q3、Q4水平时,患MAFLD风险分别增加62%(OR=1.62,95%CI:1.10~2.39)、62%(OR=1.62,95%CI:1.01~2.60)、172%(OR=2.72,95%CI: 1.53~4.84),且呈正向线性剂量-反应关系(overall=0.002).血清PFDA处于Q2、Q3、Q4水平时,可导致MAFLD风险分别减少39%(OR=0.61,95%CI: 0.44~0.85)、46%(OR=0.54,95%CI:0.34~0.84)、74%(OR=0.26,95%CI:0.15~0.45),呈负向线性剂量-反应关系(overall<0.001).亚组分析显示血清PFDA对51~65岁人群罹患MAFLD的影响更为显著,而血清PFNA对女性的影响较大.综上所述,血清PFNA及PFDA与MAFLD患病风险关联,血清PFNA暴露是MAFLD发生的重要危险因素,而血清PFDA是保护因素, 女性、中老年人群是潜在的易感人群.

全氟化合物;代谢相关脂肪性肝病;剂量反应关系

全氟化合物(PFAS)最初在1940年代和1950年代生产[1],常用于一次性食品包装、工业洗涤剂、消防泡沫或防水防油材料[2],具有热稳定性、疏水性、疏油性和极低表面张力等特点,因此在环境中分布广泛且难以降解.此外,长链PFAS在人体内半衰期极长[3],且在肝脏和其他器官内积累[4],因而被美国疾病控制和预防中心归类为持久性有机污染物.虽然近年来由于各国的监管干预措施,人类对常见 PFAS的接触逐渐减少,但其在环境中存在的普遍性和持久性仍对人类健康造成不利影响[5].研究表明, PFAS暴露与癌症[6]、甲状腺疾病[7]、免疫功能[8]、代谢紊乱[9]和肝脏损伤[10]等多种不良健康结局有关.

代谢相关脂肪性肝病(MAFLD)是2020年6月提出的一个非酒精性脂肪性肝病(NAFLD)新概念[11],其诊断不需排除其他慢性肝病,而是基于肝脂肪变性将肥胖症、代谢综合征和系统生物学的理解集中在一个焦点上[12-13].研究表明MAFLD全球患病率为38.77%[14],已成为重要的公共卫生问题.

研究表明PFAS暴露可能会增加人体代谢紊乱(如血糖、胰岛素抵抗和血脂异常)和相关代谢性疾病(如2型糖尿病和代谢综合征)发生风险[9,15-19].然而,关于PFAS与代谢紊乱的关联存在异质性,有研究提示两者并无关联甚至是相反的结果[20-23].此外,PFAS可能对肝脏造成损伤,流行病学研究表明,PFAS水平与肥胖人群肝脂肪变性相关的肝功能指数呈正相关[24],并且会引起肝酶升高[25].

代谢紊乱和肝损伤是MAFLD发生的关键因素[26].实验研究进一步表明,PFAS暴露会破坏正常的肝脏脂质代谢,导致肝脏脂肪变性[3,27].PFAS能够与脂肪酸结合蛋白[28]和过氧化物酶体增殖物激活受体a(PPAR-a)[29]结合,进而破坏肝脂肪代谢及葡萄糖动态平衡、促进炎症和MAFLD的发展.虽然关于PFAS破坏动物肝脂代谢诱发NAFLD的研究已被广泛报道,但是关于PFAS与NAFLD之间的流行病学结果很少,与新定义MAFLD的关联流行病学研究更是有限.

尽管以上大部分研究均支持PFAS的肝毒性和促进代谢紊乱,但也有不一致的流行病学结果.此外,目前也没有关于PFAS与MAFLD关联的直接流行病学证据.因此,本研究基于2017- 2018NHANES数据库,探究常见血清PFAS与MAFLD患病风险的潜在关联,旨在为PFAS与MAFLD患病风险研究提供最新流行病学证据,为重点人群筛查提供依据.

1 材料与方法

1.1 数据来源

美国国家营养调查与健康调查数据库(National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey,NHANES)是一项评估美国居民健康和营养状况的横断面调查,采用分层多阶段抽样设计每两年进行一次调查,调查数据包括人口统计、膳食、生物监测、体检和访谈等.该研究方案经美国国家卫生统计中心研究伦理审查委员会批准、参与者同意.考虑到数据库包含PFAS和肝脏超声弹性瞬时成像的年份,因此我们选取NHANES 2017~2018年的研究对象进行分析.

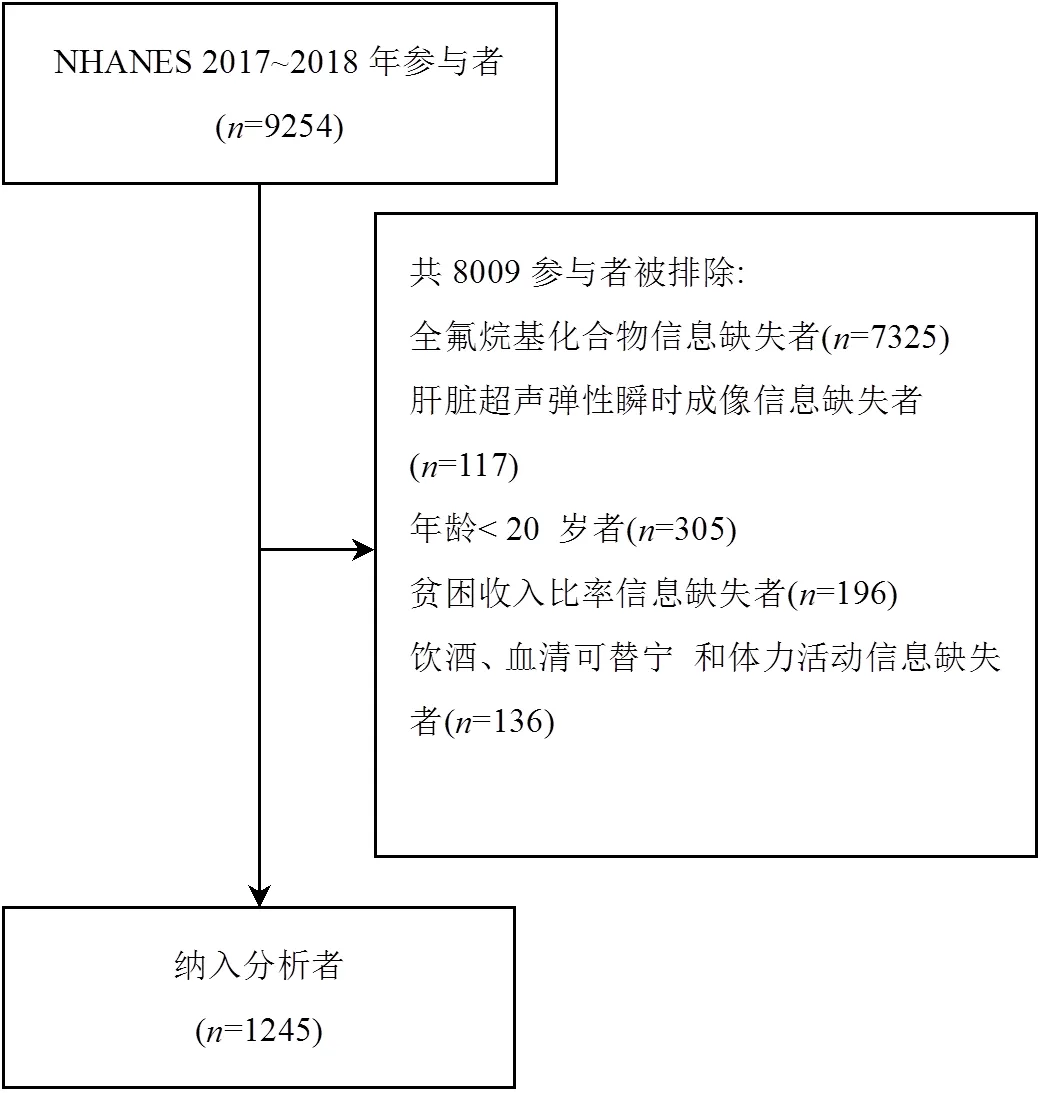

NHANES 2017~2018年数据库中共有9254个对象,研究排除缺乏PFAS血清检测(=7325)、肝脏瞬时弹性成像(=117)、年龄<20岁(=305)以及缺失多变量模型中重要协变量者(=332),最终纳入1245名研究对象,详细筛选流程见图1.

图1 研究人群筛选过程

1.2 MAFLD的定义

采用瞬时弹性成像(FibroScan®)受控衰减参数(Controlled attenuation parameter,CAP)和肝脏硬度测量(Liver stiffness measurements,LSM)分别定义肝脂肪变性和肝纤维化.本研究参照Eddowes等人的研究[30],将CAP³274dB/m定为肝脂肪变性(该临界值识别肝脂肪变性的敏感度为90%).排除禁食时间<3h、LSM完整读数少于10次或LSM四分位间距范围/LSM中位数超过30%的FibroScan®测量失败者.

根据国际专家共识声明[11],MAFLD诊断标准是基于肝脂肪变性证据有以下三个标准之一:超重/肥胖、2型糖尿病或代谢失调证据.代谢失调定义为满足以下至少两种代谢风险异常:1)男性腰围³102cm,女性腰围³88cm;2)血压³130/85mmHg或特定药物治疗;3)血浆甘油三酯异常(即血浆甘油三酯³150mg/dl或特定药物治疗);4)男性血浆高密度脂蛋白胆固醇<40mg/dl,女性血浆高密度脂蛋白胆固醇<50mg/dl或特定药物治疗;5)糖尿病前期(即空腹血糖水平100至125mg/d,或负荷后2h血糖水平140至199mg/dl或HbA1c 5.7%至6.4%);6)胰岛素抵抗评分的稳态模型评估³2.5;7)血浆高敏C反应蛋白水平>2mg/L.

1.3 血清PFAS的测定

1.4 其他变量定义

糖尿病定义根据美国糖尿病协会相关标准[31],即符合以下任何条件之一:1)自我报告诊断糖尿病.2)使用降糖药物.3)血红蛋白³6.5% (48mmol/mol).4)空腹血糖³126mg/dl.2型糖尿病的诊断是基于糖尿病诊断,排除可能的1型糖尿病患者(诊断年龄<30岁,胰岛素为唯一抗高血糖药物).

贫困收入比(Poverty income ratio, PIR): <1.3为低、1.3~3.5为中、³3.5为高.身体活动:0MET- minutes/week为不活动,1~499MET-minutes/week为低等体力活动水平,³500MET-minutes/week为中等及以上体力活动水平.

1.5 统计分析

连续变量以平均值±标准差或中位数(四分位数间距)表示,组间比较采用Student检验或Mann- Whitney检验;分类变量采用频数(百分比)表示,组间比较采用卡方检验.

首先,使用Spearman相关性评估不同血清PFAS浓度之间的相关性.其次,采用logistic回归模型以PFAS连续变量(血清PFAS值经对数变换,以10为底纠正偏态分布)和分类变量(第一分位数Q1作为参考)分别作为自变量,探究其与MAFLD发生的暴露反应关系.其中,单污染模型自变量包括单个PFAS和调整变量,多污染物模型自变量包括PFOA、PFOS、PFHxS、PFDA、PFNA以及调整变量.根据既往文献[9,32],纳入的模型调整变量包括年龄、性别、种族、贫困收入比、教育水平、身体活动、血清可替宁、饮酒.根据赤池信息准则,选取最优节点数量的限制性立方样条进一步分析PFAS暴露与 MAFLD之间的剂量反应关系.最后采用分层多元回归分析按年龄、性别、种族、贫困收入比、教育水平、饮酒状况和身体活动分层进行亚组分析,交互作用分析阐明亚组之间效应的异质性,探讨不同特征人群中MAFLD患病风险和血清PFAS浓度之间的关系.

数据分析采用R 4.1.3和SPSS25.0软件完成.所有检验均为双侧检验,检验水准=0.05.

2 结果

2.1 一般人口学特征

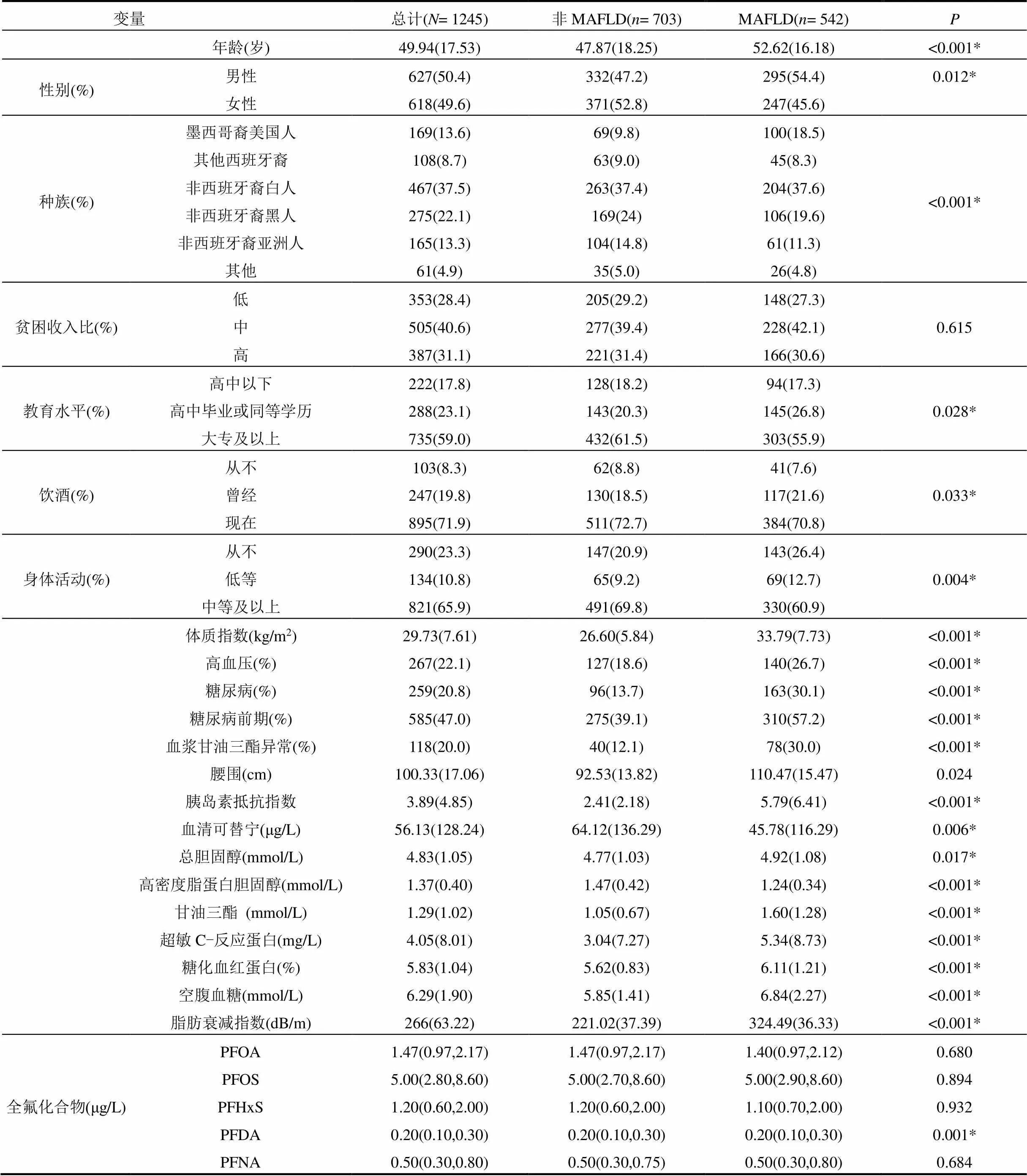

本研究共纳入研究对象1245名,其中MAFLD 542名(43.5%),男性占50.4%,平均年龄49.94±17.53岁.大多数参与者为非西班牙裔白人(37.5%),其次是非西班牙裔黑人(22.1%)和墨西哥裔美国人(13.6%).除贫困收入比外,MAFLD组与非MAFLD组年龄、性别、种族以及教育水平均存在统计学差异(<0.05).与非MAFLD患者相比,MAFLD患者平均年龄较高,高血压、糖尿病、糖尿病前期、高甘油三酯血症发生比例较高.此外血清PFDA水平在两组差异有统计学意义,见表1.

表1 一般人口学特征

注:数据描述为均值(标准差)或中位数(四分位数间距)或频数(百分比),*表示组间差异显著.

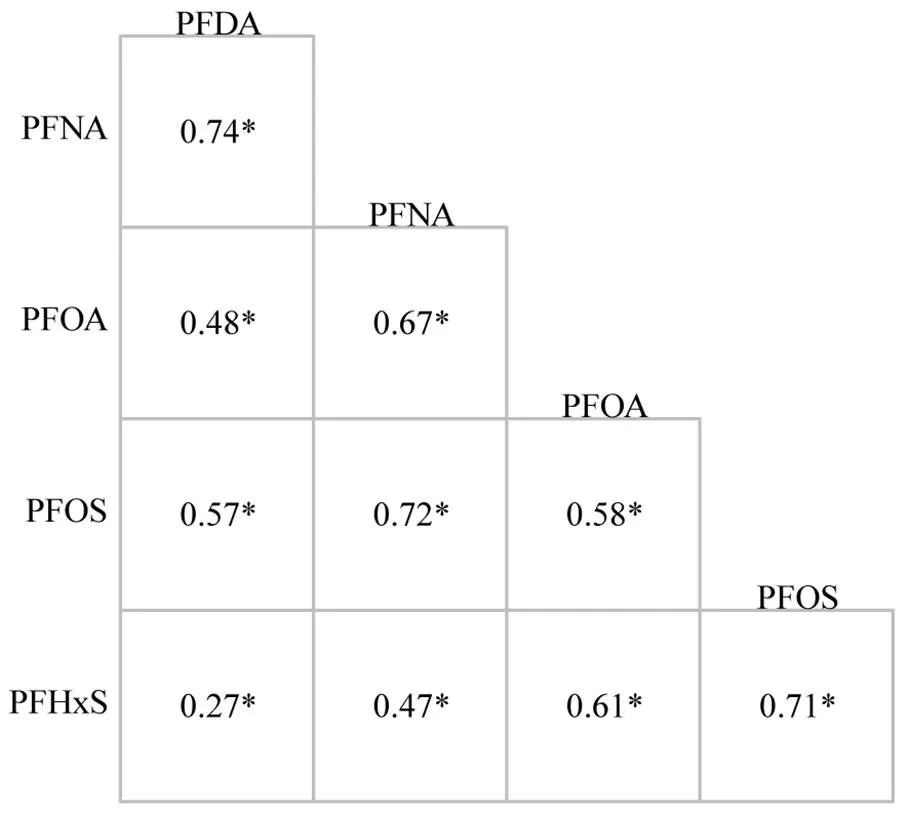

2.2 血清PFAS之间的相关性

由图2所示,5种PFAS间存在不同程度的显著相关性(<0.001),s0.27~0.74,均呈正相关.

2.3 血清PFAS浓度与MAFLD患病风险的关联

表2显示,在单污染物模型中,PFOS、PFHxS和PFDA与MAFLD风险降低相关,PFOS每增加一个单位,患MAFLD风险下降36%(OR=0.64,95%CI: 0.45~0.91),PFHxS每增加一个单位,患MAFLD风险下降35%(OR=0.65,95%CI: 0.46~0.93),PFDA每增加一个单位,患MAFLD风险下降55%(OR=0.45, 95%CI:0.30~0.67),趋势性检验均具有统计学意义(trend<0.05).

在多污染物模型中, PFDA与MAFLD发生风险降低相关(OR=0.24,95%CI:0.13~0.43),PFNA与MAFLD发生风险增加相关(OR=2.94, 95%CI: 1.58~ 5.47).以Q1组为参照,血清PFDA 的Q2组、Q3组、Q4组的OR值分别为0.61(95%CI: 0.44~0.85) 、0.54 (95%CI:0.34~0.84)、0.26(95%CI:0.15~0.45),血清PFNA的Q2组、Q3组、Q4组的OR值分别为1.62 (95%CI:1.10~2.39)、1.62(95%CI:1.01~2.60)、2.72 (95%CI:1.53~4.84),均存在剂量反应关系(trend< 0.05).

图2 血清PFAS浓度之间的相关性

*表示显著相关

表2 血清PFAS浓度与MAFLD患病风险之间的关联性

注:表中数字为OR(95%CI);OR,比值比;CI,置信区间;Q,四分位数;*为显著相关. .a:单污染物模型在调整协变量基础上一次纳入一种PFAS进入模型;b:多污染物模型在调整协变量基础上同时纳入以上5种PFAS进入模型;c:血清PFAS浓度经lg10转换.模型调整了年龄、性别、种族、贫困收入比率、教育水平、身体活动、饮酒状况、血清可替宁.

2.4 血清PFAS与患MAFLD风险的剂量反应关系

如图3所示,PFDA浓度与MAFLD患病风险呈负向线性剂量反应关系(overall<0.001,nonlinear= 0.484),随着PFDA水平增加,MAFLD患病风险降低;PFNA浓度与MAFLD患病风险呈正向线性剂量反应关系(overall=0.002,nonlinear=0.452),随着PFNA水平增加,患MAFLD风险增加.

调整因素同表2

2.5 亚组分析

图4所示为不同亚组之间血清PFDA、PFNA浓度对MAFLD患病风险的影响.血清PFDA浓度与年龄亚组之间存在显著交互作用(inter=0.023),且在51~65岁年龄组血清PFDA与MAFLD患病风险相关性更强烈.此外,血清PFNA与性别亚组也存在显著交互作用(inter=0.001),且在女性人群中血清PFNA与MAFLD患病风险相关性更强烈.

图1 不同亚组人群血清PFDA、PFNA与MAFLD患病风险的关联

*表示交互作用有显著相关性

3 讨论

本研究首次评估了美国成年人中多种血清PFAS与MAFLD患病风险的关系.单污染模型显示,血清PFOS、PFHxS、PFDA与MAFLD患病风险降低相关.多污染模型中血清PFAS没有显示一致的关联性,血清PFNA与MAFLD患病风险呈正向线性剂量反应关系,而血清PFDA与MAFLD患病风险呈负向线性剂量反应关系.

3.1 PFAS对MAFLD患病风险的影响

目前没有研究直接表明PFAS与MAFLD发生的潜在关联,只有少数流行病学研究报道PFAS有肝脏损伤以及增加代谢紊乱的风险.同样基于NHANES数据库,Gleason等探讨了四种PFAS (PFHxS、PFOS、PFOA和 PFNA)与肝功能标志物的关系,发现谷丙转氨酶随着血清PFNA水平增加而增加[33],说明PFNA对肝脏有损伤作用.此外在美国俄亥俄州200名成年人的报告中,同样观察到PFNA与细胞角蛋白-18(一种脂肪肝生物标志物)存在正相关[34].研究显示,PFAS 暴露与血液中脂质谱的改变有关,如甘油三酯、胆固醇、低密度脂蛋白升高和高密度脂蛋白降低[35-38].由于PFAS更容易引起肥胖人群血脂异常,并且 MAFLD 与肥胖密切相关,这在一定程度上说明PFAS暴露可能与MAFLD患病风险存在潜在关联.此外,MAFLD是代谢综合征的肝脏表现[39],Christense等[9]的研究发现PFNA始终与代谢综合征及其组分的风险增加相关,而PFDA呈现出与代谢综合征风险降低有关,这暗示了PFNA可能与MAFLD的风险增加有关系,而PFDA的保护性作用也与本研究结果一致.

动物实验中,有研究报道PFAS会导致大鼠和非人灵长类动物的肝脏脂质代谢异常、肝脏肿大[40],从而诱发非酒精性脂肪性肝病,可能机制是通过激活PPAR-a诱导脂肪酸b氧化导致肝脂肪积累[41]和氧化应激[42],激活的PPAR-a上调参与调节脂肪酸和胆固醇的运输与代谢以及炎症反应的PPAR-a靶基因,并与其上游的过氧化物酶体增殖物反应原件结合[43].此外,PPAR-a在PFDA诱导的肝毒性中有破坏和保护双重作用[44].PPAR-a功能在人与动物之间存在差异,因此需进一步研究来阐明人血清PFAS在MAFLD发展中的具体机制.

3.2 女性和中老年人的易感性较高

不同性别人群中PFNA相关的MAFLD风险存在差异.女性对PFAS的敏感性较高,与其他结果相似[45],这可能与男性和女性PFAS的不同毒代动力学有关[46].此外,中老年人群中血清PFDA与MAFLD患病风险相关相关效应更为强烈,考虑与中老年人生理功能衰退,对污染物的敏感性升高有关.

3.3 局限性

本研究的局限性:第一,基于横断面研究,因果关系的证据并不充分;第二,数据来自NHANES数据库,外推性受限,需在其他人群中进行验证;第三,由于 NHANES 2017~2018数据集的限制,缺乏涉及代谢风险异常的部分MAFLD诊断参数,例如负荷后2小时血糖水平和糖尿病类型,这可能会低估MAFLD患病率;第四,因研究条件的局限性,未排除职业、高脂肪饮食以及低水果和蔬菜摄入量等因素,可能导致效应估计有偏差.

4 结论

4.1 与最低四分位数浓度(Q1)相比,血清 PFNA浓度处于Q2、Q3、Q4水平时,患MAFLD风险分别增加62%、62%、172%,且限制性立方样条分析呈正向线性剂量-反应关系(overall=0.002),表明PFNA暴露是MAFLD发生的重要危险因素.

4.2 与最低四分位数浓度(Q1)相比,血清PFDA处于Q2、Q3、Q4水平时,可导致MAFLD风险分别减少39%、46%、74%,限制性立方样条分析呈负向线性剂量-反应关系(overall<0.001),表明PFDA暴露是MAFLD发生的重要保护因素.

4.3 亚组分析提示PFDA与年龄亚组存在显著交互作用(inter=0.023),PFNA与性别亚组存在显著交互作用(inter=0.001).其中,女性、中老年人群分别是PFNA效应与PFDA效应的易感人群.

[1] Lindstrom A B, Strynar M J, Libelo E L. Polyfluorinated compounds: Past, present, and future [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2011,45(19):7954-61.

[2] Kotthoff M, Müller J, Jürling H, et al. Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances in consumer products [J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2015,22(19):14546-59.

[3] Worley R R, Moore S M, Tierney B C, et al. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in human serum and urine samples from a residentially exposed community [J]. Environ. Int., 2017,106:135-43.

[4] Pérez F, Nadal M, Navarro-Ortega A, et al. Accumulation of perfluoroalkyl substances in human tissues [J]. Environ. Int., 2013,59: 354-62.

[5] Sunderland E M, Hu X C, Dassuncao C, et al. A review of the pathways of human exposure to poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) and present understanding of health effects [J]. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol., 2019,29(2):131-47.

[6] Barry V, Winquist A, Steenland K. Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) exposures and incident cancers among adults living near a chemical plant [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2013,121(11/12): 1313-1318.

[7] Dzierlenga M W, Allen B C, Clewell H J, III, et al. Pharmacokinetic bias analysis of an association between clinical thyroid disease and two perfluoroalkyl substances [J]. Environ. Int., 2020,141:105784.

[8] DeWitt J C, Peden-Adams M M, Keller J M, et al. Immunotoxicity of perfluorinated compounds: recent developments [J]. Toxicol. Pathol., 2012,40(2):300-311.

[9] Christensen K Y, Raymond M, Meiman J. Perfluoroalkyl substances and metabolic syndrome [J]. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 2019,222(1):147-153.

[10] Attanasio R. Association between perfluoroalkyl acids and liver function: Data on sex differences in adolescents [J]. Data in Brief, 2019,27:104618.

[11] Eslam M, Newsome P N, Sarin S K, et al. A new definition for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: An international expert consensus statement [J]. Journal of Hepatology, 2020,73(1): 202-209.

[12] Zheng K I, Fan J G, Shi J P, et al. From NAFLD to MAFLD: a "redefining" moment for fatty liver disease [J]. Chin. Med. J. (Engl), 2020,133(19):2271-2283.

[13] Zheng K I, Sun D Q, Jin Y, et al. Clinical utility of the MAFLD definition [J]. J Hepatol, 2021,74(4):989-991.

[14] Chan K E, Koh T J L, Tang A S P, et al. Global prevalence and clinical characteristics of metabolic-associated fatty liver disease: A meta- analysis and systematic review of 10 739 607individuals [J]. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 2022,107(9):2691- 2700.

[15] Zhang Y-T, Zeeshan M, Su F, et al. Associations between both legacy and alternative per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances and glucose-homeostasis: The Isomers of C8health project in China [J]. Environment International, 2022,158:106913.

[16] Zeeshan M, Zhang Y-T, Yu S, et al. Exposure to isomers of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances increases the risk of diabetes and impairs glucose-homeostasis in Chinese adults: Isomers of C8 health project [J]. Chemosphere, 2021,278:130486.

[17] Han X, Meng L, Zhang G, et al. Exposure to novel and legacy per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) and associations with type 2diabetes: A case-control study in East China [J]. Environment International, 2021,156:106637.

[18] Duan Y, Sun H, Yao Y, et al. Serum concentrations of per-/ polyfluoroalkyl substances and risk of type 2diabetes: A case-control study [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2021,787:147476.

[19] Yang Q, Guo X, Sun P, et al. Association of serum levels of perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) with the metabolic syndrome (MetS) in Chinese male adults: A cross-sectional study [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2018,621:1542-1549.

[20] Jeddi M Z, Dalla Zuanna T, Barbieri G, et al. Associations of perfluoroalkyl substances with prevalence of metabolic syndrome in highly exposed young adult community residents-A cross- sectional study in Veneto Region, Italy [J]. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2021,18(3):1194.

[21] Liu H-S, Wen L-L, Chu P-L, et al. Association among total serum isomers of perfluorinated chemicals, glucose homeostasis, lipid profiles, serum protein and metabolic syndrome in adults: NHANES, 2013~2014 [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2018,232:73-79.

[22] Su T-C, Kuo C-C, Hwang J-J, et al. Serum perfluorinated chemicals, glucose homeostasis and the risk of diabetes in working-aged Taiwanese adults [J]. Environment International, 2016,88:15-22.

[23] Conway B, Innes K E, Long D. Perfluoroalkyl substances and beta cell deficient diabetes [J]. Journal of Diabetes and Its Complications, 2016,30(6):993-998.

[24] Jain R B, Ducatman A. Selective associations of recent low concentrations of perfluoroalkyl substances with liver function biomarkers: NHANES 2011to 2014 data on US adults aged³20years [J]. J Occup Environ Med, 2019,61(4):293-302.

[25] Attanasio R. Sex differences in the association between perfluoroalkyl acids and liver function in US adolescents: Analyses of NHANES 2013~2016 [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2019,254(PtB):113061.

[26] Chen Y-l, Li H, Li S, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for metabolic associated fatty liver disease in an urban population in China: a cross-sectional comparative study [J]. BMC Gastroenterology, 2021,21(1):212.

[27] Das K P, Wood C R, Lin M T, et al. Perfluoroalkyl acids-induced liver steatosis: Effects on genes controlling lipid homeostasis [J]. Toxicology, 2017,378:37-52.

[28] Zhang L, Ren X M, Guo L H. Structure-based investigation on the interaction of perfluorinated compounds with human liver fatty acid binding protein [J]. Environ Sci Technol, 2013,47(19):11293-11301.

[29] Foreman J E, Chang S-C, Ehresman D J, et al. Differential hepatic effects of perfluorobutyrate mediated by mouse and human PPAR-alpha [J]. Toxicological Sciences, 2009,110(1):204-211.

[30] Eddowes P J, Sasso M, Allison M, et al. Accuracy of FibroScan controlled attenuation parameter and liver stiffness measurement in assessing steatosis and fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease [J]. Gastroenterology, 2019,156(6):1717-1730.

[31] Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: Standards of medical care in diabetes-2021 [J]. Diabetes Care, 2021,44(Suppl 1):S15-S33.

[32] Guo B, Guo Y, Nima Q, et al. Exposure to air pollution is associated with an increased risk of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease [J]. Journal of Hepatology, 2022,76(3):518-525.

[33] Gleason J A, Post G B, Fagliano J A. Associations of perfluorinated chemical serum concentrations and biomarkers of liver function and uric acid in the US population (NHANES), 2007~2010 [J]. Environmental Research, 2015,136:8-14.

[34] John, Bassler, Alan, et al. Environmental perfluoroalkyl acid exposures are associated with liver disease characterized by apoptosis and altered serum adipocytokines [J]. Environmental pollution (Barking, Essex: 1987), 2019:247:1055-1063.

[35] Lin T-W, Chen M-K, Lin C-C, et al. Association between exposure to perfluoroalkyl substances and metabolic syndrome and related outcomes among older residents living near a Science Park in Taiwan [J]. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 2020,230:113607.

[36] Spratlen M J, Perera F P, Lederman S A, et al. The association between perfluoroalkyl substances and lipids in cord blood [J]. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 2020,105(1):43-54.

[37] Jain R B, Ducatman A. Roles of gender and obesity in defining correlations between perfluoroalkyl substances and lipid/lipoproteins [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2019,653:74-81.

[38] Christensen K Y, Raymond M, Meiman J. Perfluoroalkyl substances and metabolic syndrome [J]. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health, 2019,222(1): 147-153.

[39] Kim C H, Younossi Z M. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a manifestation of the metabolic syndrome [J]. Cleve Clin J Med, 2008, 75(10):721-728.

[40] Lau C, Anitole K, Hodes C, et al. Perfluoroalkyl acids: a review of monitoring and toxicological findings [J]. Toxicol. Sci., 2007,99(2): 366-394.

[41] Wan H T, Zhao Y G, Wei X, et al. PFOS-induced hepatic steatosis, the mechanistic actions on β-oxidation and lipid transport [J]. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 2012,1820(7):1092-101.

[42] Khansari M R, Yousefsani B S, Kobarfard F, et al. In vitro toxicity of perfluorooctane sulfonate on rat liver hepatocytes: probability of distructive binding to CYP 2E1and involvement of cellular proteolysis [J]. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int., 2017,24(29):23382-8.

[43] Feige J N, Gelman L, Michalik L, et al. From molecular action to physiological outputs: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors are nuclear receptors at the crossroads of key cellular functions [J]. Progress in Lipid Research, 2006,45(2):120-59.

[44] Luo M, Tan Z, Dai M, et al. Dual action of peroxisome proliferator- activated receptor alpha in perfluorodecanoic acid-induced hepatotoxicity [J]. Archive für Toxikologie, 2016,91(2):1-11.

[45] Sen P, Qadri S, Luukkonen P K, et al. Exposure to environmental contaminants is associated with altered hepatic lipid metabolism in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease [J]. Journal of Hepatology, 2022, 76(2):283-293.

[46] Harada K, Inoue K, Morikawa A, et al. Renal clearance of perfluorooctane sulfonate and perfluorooctanoate in humans and their species-specific excretion [J]. Environ. Res., 2005,99(2):253-261.

Relationship of serum perfluoroalkyl substances with the risk of metabolic associated fatty liver disease.

ZHANG Lu-lu, LIU Jing, HE Ying-qian, ZHAO Ya-nan, ZHENG Shan, WANG Min-zhen*

(Institute of Epidemiology and Statistics, School of Public Health, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou 73000, China)., 2023,43(2):964~972

To explore the effect of serum perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) on the metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) on the basis of the 2017~2018 US National Health and Nutrition Survey (NHANES) database. The logistic regression model and restricted cubic spline (RCS) were used to evaluate the association and dose-response relationship between PFAS and MAFLD. The main results showed that in a single pollutant model, perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS), perfluorohexane sulfonic acid (PFHxS) and perfluorodecanoic acid (PFDA) were negatively associated with the risk of MAFLD, with the ORs of 0.64 (95%CI:0.45~0.91), 0.65 (95%CI:0.46~0.93) and 0.45 (95%CI:0.30~0.67), respectively. In the multi-pollutant model, compared with the lowest quantile (Q1), the risk of MAFLD increased with the increase of perfluoronanoic acid (PFNA) by 62% (OR=1.62, 95%CI:1.10~2.39), 62% (OR=1.62, 95%CI:1.01~2.60) and 172% (OR=2.72, 95%CI: 1.53~4.84) at Q2, Q3, and Q4, respectively. Conversely, there was negative linear dose-response relationship (overall<0.001) between PFDA and the risk of MAFLD. The risk of MAFLD were 0.61(95%CI: 0.44~0.85), 0.54(95%CI: 0.34~0.84) and 0.26(95%CI: 0.15~0.45) when the concentration of PFDA reached to Q2, Q3, and Q4 levels. Subgroup analysis showed that serum PFDA had a more significant effect on the risk of MAFLD in 51~65 years old population. Females exposed to serum PFNA were more likely to develop MAFLD. In conclusion, serum PFNA and PFDA were significantly related to the risk of MAFLD, and PFNA exposure played a risky role in the occurrence of MAFLD while PFDA had protective effect. Women, middle-aged and elderly people might be potential susceptible groups.

perfluoroalkyl substances;metabolic associated fatty liver disease;dose-response relationship

X503.1;X18

A

1000-6923(2023)02-0964-09

张露露(1998-),女,江西南昌人,兰州大学硕士研究生,主要从事环境流行病学研究.

2022-07-06

国家自然科学基金资助项目(41705122)

* 责任作者, 副教授, wangmzh@lzu.edu.cn