边缘景观在蓝绿空间系统中的贡献

——以西班牙维多利亚-加斯蒂兹“翡翠与蓝宝石项链”为例

著:(巴西)卡米拉·戈梅斯·圣安娜 译:龙林格格 校:李梦一欣

面对气候变化与流行性疾病日益显著的影响,景观被认为是能够构建可持续城市发展的基础设施,它将土地利用与地区自然发展、生物和非生物特征以及其文化、美学和遗产表现形式联系在一起[1]。

北美风景园林师弗雷德里克·劳·奥姆斯特德(1822—1903)在其先驱性设计方法中指出,可通过阐明景观的基础设施问题来实现规划和设计功能。他用技术性的方法回应了城市需求(城市化和自然资源相协调),同时也提升了城市景观的生态、美学、社会和文化价值[1-2]。因此,对于城市边缘景观而言,蓝绿开放空间作为整体形成了一个景观系统,而不再是一个孤立的要素[1-7]。

2022年是奥姆斯特德200周年诞辰,为了纪念他,许多机构组织了各类讨论、展览和会议,例如“现在的奥姆斯特德”(olmstednow.org/)线上展览讨论了奥姆斯特德对于建设更好城市做出的重要贡献。在当代范式下重新审视奥姆斯特德的实践,是应对气候变化影响的基础[1]。在此背景下,考虑到西班牙最近有关构建城市蓝绿空间网络的建议,“翡翠与蓝宝石项链”是实施多尺度绿色基础设施策略的案例,其将蓝绿系统纳入同一个网络,促进了自然、社会和生产过程,并与区域的建筑基础设施相结合[8],保证了生物多样性和公共健康[9]。

绿色基础设施(GI)已经成为规划和设计复杂景观的综合策略。然而,GI对于整合边缘景观中的废弃地、缺乏基础设施的场地和(或)棕地等区域边缘地区的能力还没有获得过多探索。边缘景观存在于边缘区域及其社区,是评估区域城市发展模式的至关重要的空间。传统意义上,边缘景观的建设往往忽略当地的自然与文化,也忽视居住在此的人群。人们更加关注能够促进城市旅游和遗产的景观,这些景观因其遗产、经济和文化特点而被认可。

事实上,不能简单地以缺失和排斥为特征,从否定主义的角度理解边缘地区,而是应该基于边缘地区对设计公平城市蓝绿空间的作用,结合弹性和教育的特征,将它们理解为异质性、生物多样性和动态的空间[10],将城市内部、边缘和外部的生产性景观结合起来。

笔者以西班牙维多利亚-加斯蒂兹为案例,对如何规划和设计“翡翠与蓝宝石项链”开展研究,以此阐释奥姆斯特德理论中提出的边缘景观的重要性。

1 波士顿奥姆斯特德翡翠项链的边缘景观

在波士顿翡翠项链(1878—1880年)的绿色开放空间方案中,奥姆斯特德与他的合作者查尔斯·艾略特(1859—1957)巩固了绿色开放空间系统的想法,使其在土地利用规划中成为关键基础设施。这些绿色开放空间从区域到地方,在不同尺度上衔接了当地的水生环境、生态空间、娱乐空间和交通系统[1,6,11]。

基于这一想法,他们创造了一个绿色空间系统——由公园大道(也被称为公园路)将波士顿公园和富兰克林公园连接起来[12]。这个系统使公共空间重新恢复活力,并将边缘景观与城市的其他区域连接起来,确保了这些适于漫步和通行的大道的连接性和质量,并重新建立了水与城市绿地系统的关系。

1.1 奥姆斯特德波士顿方案中的蓝宝石项链

奥姆斯特德波士顿方案中的水系统——“蓝宝石项链”,在连接边缘景观上发挥着重要且弹性的作用。例如受潮汐、浑河和查尔斯河洪水影响的后湾沼泽区,其在技术上响应了调节水文循环的需求,种植了能够耐受该地区咸水的植物[3]。在方案中,奥姆斯特德创造了一种来源于绘画和自然主义美学灵感的有机设计方法,尽管深受浪漫主义影响,但他用较少的元素探索了物种的季节性和恢复力[12]。

景观策略在绿色和多功能基础设施解决方案的基础上,创造了一个靠近自然与社区并融入了边缘地区的波士顿河畔。因此,奥姆斯特德对蓝绿开放系统的贡献被认为是绿色基础设施策略的奠基思想,即GI以边缘景观为基础,成为今天重新探讨城市景观规划和设计的一种方式。

1.2 维多利亚-加斯蒂兹的绿色基础设施策略和“翡翠与蓝宝石项链”

维多利亚-加斯蒂兹是西班牙巴斯克自治区的首府,是该地区最大、布局最紧凑的城市,占地276.08 km2,拥有253 093名居民[13]。支撑维多利亚-加斯蒂兹的城市绿色基础设施网络的方法策略确定于2013年。在这里,绿色基础设施作为一个“战略性规划的自然、乡村和城市绿地网络(包括河流及其他形式的水系),提供广泛的社会生态系统服务,推动环境、社会和经济效益,并促进城市居民的健康”[5]。

GI策略是为了促进城市的复兴,与保护生物多样性和气候变化计划形成对话,以强化对维多利亚-加斯蒂兹2012年欧洲绿色之都的认可(图1)。“翡翠与蓝宝石项链”方案旨在将维多利亚-加斯蒂兹1/3的区域转化成公共空间,为居民创造人均45 m2的绿色区域[14]。

1 维多利亚-加斯蒂兹的绿色之都标志Vitoria-Gasteiz green capital symbol

在西班牙,每个自治区都有3年的时间根据欧盟委员会相关导则《绿色基础设施——提升欧洲的自然资本》(2013年)来制定自适性绿色基础设施策略。西班牙第33/2015号法律涉及自然遗产和生物多样性保护,并借鉴欧洲关于GI的法律,帮助实施绿色基础设施与生态连接、修复的国家战略。然而,上述导则侧重于介绍GI的概念、原则及组成要素,并未提供一个针对地方的多尺度和多功能方法。

在Tojo[15]看来,西班牙的GI策略有一个共同点是将基础设施作为生态网络与城市系统间的一个连接要素。这正是维多利亚-加斯蒂兹地区及其绿色基础设施系统的情况,“其被定义的前提是,如果将城市绿地中包含的自然与半自然空间整合到同一个系统中并得到系统的管理时,会带来更大的效益”[13]。

1.3 维多利亚-加斯蒂兹的绿色基础设施的方法性策略:重新考虑边缘景观

维多利亚-加斯蒂兹的绿色基础设施规划和设计所采用的方法性策略回应了奥姆斯特德理论。该策略创造了区域的分层解读方法,以便于理解景观作为基础设施在一个GI区域网络的结构。先从边缘区域开始,试图分析该城市在阿拉瓦中央生物区的融入及生态问题。维多利亚-加斯蒂兹是坎塔布连山-比利牛斯山脉-法国中央高原-西阿尔卑斯山这一宏伟生态走廊中最突出的生物多样性保护区之一;同时,它也在伊比利亚半岛北部地区和泛欧洲生态网络方面发挥着主导作用。

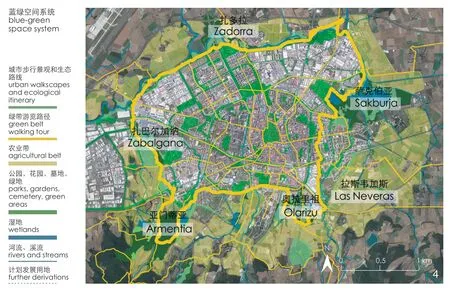

通过叠加各类地图来确定该地区蓝绿空间的特征,并以此在景观设计中整合边缘区域。区域尺度上,景观基础设施规划和设计考虑了具有环境效益的保护空间网络、自然公园、受保护的群落生境、具有重要遗产意义的乔木类型、欧洲自然保护区网络(Natura 2000)、《拉姆萨尔公约》中的湿地保护区网络、阿拉瓦生物区目录中的独特景观单元网络以及领土环境保护区域。地方尺度上,确定了翡翠与蓝宝石项链蓝绿空间的构成元素,包括公园、花园、墓地、绿地、森林、灌木丛、草地、农田、菜地、湿地、河流、溪流及其他计划发展用地(图2)。

2 维多利亚-加斯蒂兹的边缘绿带Marginal green belt in Vitoria-Gasteiz

笔者根据分析的结果,确定了这一紧凑城市在平原边缘景观中的作用。为了遏制城市的扩张,1995年在边缘景观中建设了绿带和农业带,并通过建设GI来恢复生态退化区域(图3),在这里,边缘地区做出了必不可少的贡献。

3 边缘农业带The marginal agriculture belt

接下来,建立城市分层解读体系,解析与水网(包括地下水、河流、溪流、堤坝、湿地和下水管网)有关的城市基础设施、绿带中具有环境效益的公园及城市绿色斑块之间的关系。此外,在绿地和城市地块中还包括主要位于边缘地带的以空置、废弃和(或)棕地为特征的零散区域。然后,将上述各类元素叠加在一起,并添加其他信息,如农业带、公共游览路径(小径、步行道等)和可持续的移动基础设施。通过建设城市步行景观、生态路线以及绿带步行游览路线,使物理层面和生态层面的迁移都变得更加容易,从而促进系统中边缘地带的连接度(图4)。

4 蓝绿空间系统The blue-green space system

2 维多利亚-加斯蒂兹边缘地区的翡翠与蓝宝石项链策略

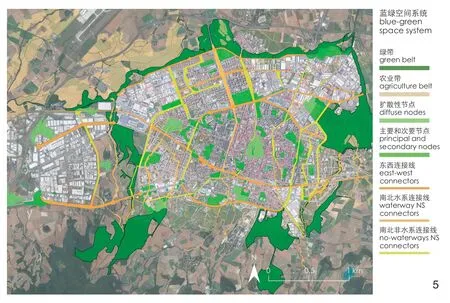

GI策略确定了现有的基础设施网络与区域物理、生态和文化联系的关系,并定义了一个将核心要素、节点元素和连接线集合在一起的蓝绿系统网络。生态观点通过汲取景观生态学理论[16-19]原则被深化。在此基础上,使用以下术语:1)核心要素,是指在毗邻城市的区域,具有高度的自然性和处于充分保护状态的空间;2)节点,位于城市内的绿色空间,由于其规模和位置,可代表城市绿地系统的基本组成部分;3)连接线,具有线性性质的景观元素,主要功能是加强核心要素和节点之间的连接[14]。

维多利亚-加斯蒂兹的边缘绿带、农业带的核心要素为“总面积为1 016 hm2的环境效益区(889 hm2为城郊公园,127 hm2为农业区)”[14]。其中,公园、广场、花园和草地是展现环境特征的节点,占据着城市外围和中心区域,具有边缘地区滨河景观的特征。

大多数节点是被定义和划定出来的空间,一般依据其重要性分为主要节点和次要节点。扩散在各处的场所空间可以作为建筑元素,承载某种使用类型,例如立体绿化和屋顶绿化。连接线是衔接节点和核心元素的线性元素,它包含传统的绿廊和水系,连接边缘地区内部以及边缘与区域中心。主要的连接策略包括组织东西连接线、南北水系连接线和南北非水系连接线(图5)。

5 由核心要素、节点元素和连接线组成的生态系统The definition of an ecological system that articulates core elements, node elements and connectors

今天重新讨论奥姆斯特德理论,形成了一种系统地理解生态过程和其他基础设施的方法。景观作为一种基础设施,被从多维尺度(不同的基础设施、时间性、连接性和功能性)来规划和设计,以适应气候变化和保护生物多样性的城市。在这种情况下,重塑策略定义了一条“蓝绿项链”,不同于传统的规划和设计,它关注边缘区域。由此,边缘地区成为主角,强化了绿带和农业带的当代价值。

2.1 翡翠与蓝宝石项链:公园在边缘区域的作用

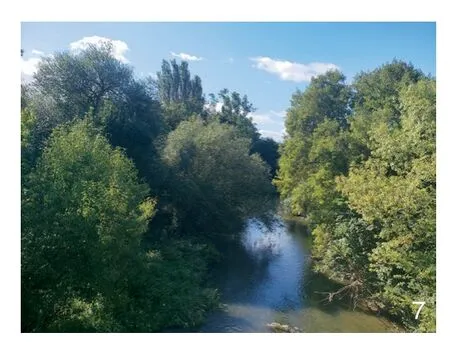

维多利亚-加斯蒂兹的边缘区域存在一些公园,包括扎巴尔加纳公园(图6)、扎多拉公园(图7)、奥拉里祖公园(图8)、萨尔布鲁阿湿地公园(图9)和亚门蒂亚公园(图10)。它们在生态网络和水网中发挥着核心要素的作用,或与绿带和农业带呼应,或与开放空间系统相连,使人们能够参观城市主要的遗产景观。同时,公园中还展示了乡村景观,促使人们重新思考社区与城市边缘及其滨河景观的关系。

6 扎巴尔加纳公园Zabalgana park

7 扎多拉公园Zadorra park

8 奥拉里祖公园Olarizu park

9 萨尔布鲁阿湿地公园Humedales de Salburua park

10 亚门蒂亚公园Armentia park

正如奥姆斯特德的策略中,水系这条“蓝宝石项链”在边缘区域景观设计中扮演了一个主导和弹性的角色,有助于从技术和美学角度建构公园系统。同时,也促进了区域内物理与生态上的联系。

2.2 从民主层面重新思考边缘地区

从民主层面来看,对于维多利亚-加斯蒂兹而言,奥姆斯特德提出的蓝绿空间系统不仅实现于公园中,还应用于步行和骑行的绿色路径中,这些路径让城市居民有更多机会接触这些空间和其承载的项目(如奥拉里祖植物园,阿塔利亚自然湿地中心等);其主要目标之一是“促进与绿色空间兼容的公共使用方式,增加休闲和娱乐的机会,提高可达性以及州与城市的联系,保护文化遗产和传统景观,增强地方认同感和归属感”[14]。

社区通过组织研讨会、讲座和展览等实现奥姆斯特德理论的创新,加强了其从项目开始到结束的参与度。如在区域内开展“认领一棵树”种植活动、建造家庭花园、学校及城市花园等项目,提高人们对边缘景观中绿色基础设施网络及蓝绿空间作用的认识。此外,还有制定生物多样性清单、邀请社区人群采用自行车或步行的方式游览或免费参观边缘区域等方式。

3 边缘地区的翡翠与蓝宝石项链:扎多拉公园项目

重新研究奥姆斯特德理论并结合景观生态学理论,可以看出绿色基础设施是基于蓝绿系统的整体利益来定义的,但其中的每个要素都很重要。扎多拉河是维多利亚-加斯蒂兹市的主要河流,从区域层面看,由于其生物多样性高度集中,它成为欧洲自然保护区网络的组成部分。扎多拉公园位于城市北部地区,沿其13 km的线性公园限制了城市向北扩张,构成了城市的绿带。到目前为止,这个线性公园只有2个区段得到了实施。

3.1 以农业区与滨水区连接城市与乡村不同规模的边缘景观

绿道、自行车道和小径将公园与周围环境连接起来,主要是与该地区的农业区相连。该项目寻求从城市到乡村景观的过渡,以绿带,尤其是以具有较高生态价值和具有历史、艺术意义的农业区来突出绿色开放空间系统的作用。

在边缘景观的生态设计中,可食用植物景观和水景占据了突出地位,并使用具有韧性的本地物种,渗透着自然主义原则。这些最细微的要素帮助使用者识别场地的植被结构,且只需要少量维护。植物类型的选择也受制于当前的水量情况,由于该地区面临严重的水灾问题,因此当地提出建设一个可持续的排水系统,以优化排水性能,效仿奥姆斯特德的实践。

3.2 利用废弃的区域与低价值的植物展现边缘景观的野性

奥姆斯特德在景观中人为地创造了一种野性美学,将这种美学特征融入城市天际线或许可以使整个社区更接近自然,并促使每个空间使用者都可以感知这一天际线下的荒野景观[3-4]。在维多利亚-加斯蒂兹地区,蓝绿空间也成为重新思考区域边缘化、退化以及无人居住地区的一种方式,其通过恢复生态、种植本地物种、创造不同的栖息地、提高复原力和生物多样性,在人类和自然-文化之间的互动中逐步实现了过渡(图11)。

11 位于戈莫拉区的扎多拉公园Zadorra park at the Gomorra Section

这一理念已经被应用在城市的生态和社会文化网络设计上,通过营造更多具有自然植被的地貌,展现场所的动态变化,使场所更易于管理并得到社区认可。这一过程展现了人们因城市的过度建设,正在失去对自然的体验。而在不同的时间和条件下,奥姆斯特德重视并努力恢复这种体验。

边缘地区涉及农业区、滨水地带、废弃地区和利用价值较低的植物。边缘景观作为主角,从物理上、生态上和美学上将边缘区域联系起来。除了从绿带到公园的多尺度GI规划和设计建议,在重新探求奥姆斯特德理论的今天,区域中的不同社区也成为景观的一部分,并成为景观建设的主力军[20]。

4 总结

重新审视奥姆斯特德的翡翠项链理论是研究景观作为城市可持续发展基础设施的根本,尤其是在我们面对解决气候变化和生物多样性匮乏的问题时。在这一背景下,在GI策略与项目中定义了蓝绿开放空间系统,体现了在多种尺度中景观不同层面的特征。

当从第一次解读项目开始并建立方法性战略时,这种多尺度的维度就体现出来了。人们试图基于生态、美学、社会和文化价值等维度来理解区域空间,通过整合各类地图和信息来确定立意,然后转化为项目的形式。

维多利亚-加斯蒂兹的景观基础设施的总体设计以景观生态学理论为前提,特别关注通过加强物理和生态连接促进生物多样性,从而达到降低该地区绿色区域破碎化程度的目的。通过这种方式,发展出了由核心要素、节点元素和连接线组成的生态网络。识别当地的蓝绿空间系统要素,并按照其在生态网络中的重要性,以核心要素、节点元素和连接线的方式组织起来,总体设计加强了对“翡翠”——绿色空间和“蓝宝石”——水系的理解。

在地方尺度,其想法是利用生态环境修复,用本地物种和基于自然的解决方案拉近自然和人类的距离。这为奥姆斯特德将野生环境与城市结合起来的思想提供了一个现代视角。在基于自然的解决方案和现代技术的基础上创造了一个人工系统结构,这很有可能促使社区人群在水的引导下去感知和改造他们的边缘景观。正如奥姆斯特德的实践,维多利亚-加斯蒂兹尤为注意为边缘区域的滨河景观提供技术性和艺术化的解决方案。同波士顿翡翠项链一样,这里的蓝绿空间系统将重点放在边缘空间对区域翡翠和蓝宝石项链的作用上,并重视已有的绿带和农业带。

从城市边缘景观的角度来考虑城市景观规划,还可以增强城市与乡村的连接度,修正区域中生产性景观的下降趋势,并纠正将乡村视作与自然无关的生产区的误解。生产性景观被有效地理解并纳入不同的尺度中,例如给公园提供观赏农业区的绝佳视野,或加入乡间小径、城市花园和家庭花园等元素中。

维多利亚-加斯蒂兹的“翡翠与蓝宝石项链”为反思如今传统的规划设计实践提供了借鉴和参考,让边缘景观成为策略的驱动力,并纳入城市规划设计。边缘景观在构建绿带、农业带、水网和其他绿色轴线方面举足轻重,在物理和生态层面连接了蓝绿空间系统;而在生态与社会文化层面则考虑了对该地区未来的决策,并做了大量的工作来提高社区对景观的认知,如营造步行景观和认养树木活动。社区不仅能感知景观,也成为景观的一部分,保障了其对景观的权利,延续奥姆斯特德提出的公园民主价值。

值得指出的是,目前全球有29%的城市人口住在贫民窟[21],且有大部分人生活在郊区,这与维多利亚-加斯提兹的情况完全不同,他们缺乏城市基础设施和公平权利的保障。同时,郊区是《巴黎协定》和《生物多样性公约》尝试保护的环境利益区。因此,这一经验可以为其他国家提供灵感,以地方性的方法重新研究边缘地区,并更新和再次思索今天的奥姆斯特德理论。

图片来源:

图1、6~11©卡米拉·戈梅斯·圣安娜;图2~5©卡罗琳·费尔南德斯,来源于https://www.vitoria-gasteiz.org/j34-01w/catalogo/portada?idioma=es。

(编辑/李清清)

Contribution of Blue-Green Space System in Marginal Landscape: A Case Study of the “Emerald and Sapphire Necklace” in Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain

Author: (BRA) Camila Gomes Sant’Anna Translator: LONG Lingege Proofreader: LI Mengyixin

Facing the increasingly significant impacts of climate change and the pandemic, the landscape is understood as the infrastructure capable of structuring sustainable urban development that brings together land use in line with the natural processes of the place, its biotic and abiotic characteristics and its cultural, aesthetic and heritage expressions[1].

In the pioneering approach of the North American landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted(1822-1903), planning and design function by articulating the infrastructural issues of the landscape.They bring up technical answers to the demands of the city (urbanization and natural resources),as well as promote ecological, aesthetic, social and cultural values[1-2]. Therefore, green and blue open spaces are understood as a whole, considering the marginal landscape, forming a system that frames the landscape, no longer as an isolated element[1-7].

This year is the celebration of Olmsted’s Bicentennial. Therefore, many institutions are organizing debates, exhibitions and conferences,for example, the initiative “Olmsted Now”(olmstednow.org/), to debate the most significant contribution Olmsted made to building better cities.Rethinking Olmsted’s practice, under contemporary paradigms, emerges as fundamental to facing the impact of climate change[1]. Within this context,considering recent Spain proposals for urban blue-green spaces networks, the “emerald and sapphire necklaces” are examples of multi-scale green infrastructure strategies. They include the green and blue systems in a network that promotes natural, social and productive processes, integrating with the built infrastructures of the territory[8]to guarantee biodiversity and public health[9].

Green infrastructure (GI) has already become consolidated as a strategy to plan and design the landscape in its complexity. However, there has not been much exploration of its ability to integrate the territory’s peripheral areas, embracing its obsolete areas, lacking infrastructure and/or brownfields,which are present in its marginal landscapes. The marginal landscape exists in peripheral territories and their communities, which are essential spaces for reviewing the territory’s urban development paradigm, which has traditionally disregarded nature and culture and, often, the population that inhabits it. There has also been a greater focus on promoting city touristic and heritage landscapes, understood as those recognized for their heritage and economic and cultural characteristics.

The issue involves not simply understanding these margins from a negationist perspective,marked by absence and exclusion, but rather understanding them as heterogeneous, biodiverse and dynamic spaces[10]based on their contribution to the design of equitable urban blue and green spaces, resilient and educational, which bring together the productive landscapes inside, on the margins and outside the cities.

Having carried out the study to understand how to plan and design “sapphire and emerald necklaces”in the case study of Vitoria-Gasteiz in Spain demonstrates the importance of considering marginal landscapes as introduced in Olmsted’s theory.

1 The Marginal Landscape at the Boston Olmsted Emerald Necklace

In Boston, in the proposal for green open spaces, known as the Emerald Necklace (1878-1880), Olmsted and his collaborator Charles Eliot(1859-1957) consolidated the idea of a green open space system that works as key infrastructure in the design of the land use. These green open spaces articulated aquatic, ecological, recreational and transport systems at different scales of the territory, from regional to local[1,6,11].

Based on this idea, a green-space system was created, structured by park avenues—known as parkway, that link Boston Common with Franklin Park[12]. This system renatured spaces and joined the marginal landscape with the city’s other areas,ensuring the connection and quality of these avenues, suitable for strolling and promenading,reestablished a new relationship with the water and green space systems of the city.

1.1 The Sapphire Necklace in Olmsted’s Boston Proposal

The water system, “sapphire necklace”, in Olmsted’s Boston proposal has an important and resilient role in connecting marginal landscapes.In the Back Bay swamp area, for example, it technically responds to the need to regulate the hydrological cycle, associated with the planting of species resistant to the brackishness of the territory, visited by the tides and subject to the floods of the Muddy River and the Charles River[3].In his proposal, Olmsted developed an organic design inspired by painting and naturalist aesthetics;although still very influenced by the Pittoresque vision, he explored the seasonality and resilience of species using few built the elements[12].

This landscape strategy created a Boston riverside incorporated the margins, based on green and multifunctional infrastructure solutions, that approximated nature and community. Therefore,Olmsted’s contributions to the green-blue open system are considered precursors ideas for the proposal of green infrastructure—GI as a way to rethink the landscape planning and design of the city today, having the marginal landscape as a base.

1.2 GI Strategies and the “Sapphire and Emerald Necklaces at City of Vitoria-Gasteiz”

Capital of the Basque Autonomous Community, Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain, is the area’s largest and most compact city. It covers 276.08 km2and has a population of 253,093 habitants[13].The methodological strategies for defining the urban green infrastructure network of Vitoria-Gasteiz emerged in 2013. In this context, GI is a “strategically planned network of natural, rural and urban green spaces (including rivers and other forms of water). These are managed in order to offer a broad range of socio-ecosystem services that provide environmental, social and economic benefits and for the health of the inhabitants of the city”[5].

These strategies were developed to promote the renaturing of the city in dialogue with the conservation biodiversity and climate change plans in order to strengthen the recognition of Vitoria-Gasteiz as the European Green Capital of 2012 (Fig. 1). The Vitoria-Gastiez sapphire and emerald necklaces transformed a third of its areas into public spaces and created 45 m2of green areas per inhabitant[14].

In Spain, each autonomous municipality has three years to develop their own GI strategies based on the European Commission’s guidelines onGreen Infrastructure(GI)—Enhancing Europe’s Natural Capital(2013). The Spanish legislation 33/2015, which refers to natural heritage and biodiversity, incorporates European legislation on GI, implementing the national strategy for green infrastructure and ecological connectivity and restoration. However, as the European Commission’s guidelines focus on presenting the concept, the principles and the elements of GI,instead of proposing also a multi-scale and multifunctional methodological place-based approach.

For Tojo[15], a common aspect of the GI strategies in Spain is the proposal of infrastructure as an articulating element between ecological networks and city systems. This is the case of Vitoria-Gastiez and its green infrastructure system, which “has been defined based on the premise that the natural and semi natural spaces included in urban green areas provide greater benefits when these are integrated in a system and are managed systematically”[13].

1.3 Vitoria-Gasteiz GI Methodological Strategies:Reconsidering the Marginal Landscape

Methodological strategies adopted by Vitoria-Gastiez green infrastructure plan and design bring answers to rethinking Olmsted’s theory. A layered reading of the territory was developed to understand landscape as infrastructure, structured in a GI regional network. First, it tried to understand the insertion of the city in the Álava Central Bioregion and its ecological aspects, starting at the margins of the territory. Vitoria-Gasteiz, stands out as one of the great biodiversity reserves of the great ecological corridor of the Cantabrian Mountains-Pyrenees-Massif Central-West Alps. It also plays a leading role in relation to the Iberian Peninsula’s northern region and the Pan-European Ecological Network.

Cartographies were superimposed, aiming to identify the characteristics of the green-blue spaces of the region, seeking to integrate the margins in this landscape design. In territory scale, this took into account the network of protected spaces of environmental interest, natural parks, protected biotopes, arboreal types of heritage importance,European Network of Protected Natural Areas(Natura 2000), the network of conservation zones of wetlands of theRamsar Convention,the network of singular landscape units present in the catalog of the bioregion, the Alava Plains, and the areas of territorial environmental protection.In local scale, the elements of the sapphire and emerald green-blue spaces were identified: parks,gardens, cemeteries, green spaces, forests, thickets,meadows, crops, vegetable plots, wetlands, rivers,streams and further derivations (Fig. 2).

As a result of this analysis, the role of this compact city from its landscape on the margin of the plain was identified. In the marginal landscape,the green and agricultural belt was implemented in 1995 to contain the urban sprawl and of recovering ecologically degraded areas through the creation of GI, where the margins make a fundamental contribution (Fig. 3).

The next step was to establish a layered reading, which demonstrated the relationship between urban infrastructures related to the water network (aquifer, rivers, streams, dykes,wetlands and sanitation network), the parks of environmental interest in the green belt, and the urban green plot. In addition, fragmented areas characterized by vacant, obsolete and/or brownfields were also identified in the green and urban plot, mainly on the margins. After that, these readings were overlaid and other information was added: agricultural belt, public tours (paths and boardwalks, among others) and sustainable mobility infrastructure. The connectivity of the margins in the system is promoted by making physical and ecological movements easier, with urban walkscapes and ecological itinerary and green belt walking tour(Fig. 4).

2 The Strategy of the Emerald and Sapphire Necklace in the Vitoria-Gasteiz Margins

The relationship between the existing infrastructure network and the territory’s physical,ecological and cultural connections was identified,with the definition of a blue-green system network that brings together core elements, node elements and connectors. The ecological perspective was deepened by incorporating the principles of the Theory of Landscape Ecology[16-19]. In the context,the following terms were used: 1) Core elements,spaces with a high level of naturalness and an adequate state of conservation in areas adjacent to the city; 2) nodes, green spaces located within the city, which, due to their size and/or location,represent basic structural parts of the urban green system; 3) connectors, elements of a linear nature,the main function of which is to facilitate the connection between core elements and nodes[14].

The green and agricultural belt in Vitoria-Gasteiz has core elements that are understood as areas of environmental interest of “a total surface area of 1 016 hm2(of which 889 hm2correspond to periurban parks and 127 hm2to agricultural areas”[14]. Parks, squares, gardens and meadows are among the features considered nodes, occupying the peripheral and downtown area, characterizing the riverside landscape in margins.

Most nodes are defined and delimited spaces,organized into main or secondary, depending on their importance. Diffuse places are elements present in buildings that can receive some type of use, such as green walls and green roofs.Connectors are linear elements that articulate nodes and core elements, which incorporate traditional green corridors and waterways linking parts of the marginal region itself and this with the central area of the territory. The principle connection strategies are organized in the east-west connector, waterways north-south connectors and no-waterways northsouth connectors (Fig. 5).

The result of Olmsted’s theory rethought today produces a methodology for understanding integrated ecological processes and other infrastructures systematically. Landscape is seen as infrastructure, exploring its multiple dimensions(different infrastructures, temporalities, connectivity and functionality) to plan and design climateadapted and biodiverse cities. In this context, the renaturing strategies defined a “green and blue necklace” that differed from traditional planning and design in that it embraced the margins.Therefore, the margins gain protagonism and reinforce the value of the green and agriculture belt in the contemporary context.

2.1 The Emerald and Sapphire Necklace: The Role of the Parks in the Margins

In the case of Vitoria-Gastiez, there are parks in its marginal areas: Zabalgana (Fig. 6),Zadorra (Fig. 7), Olarizu (Fig. 8), Humedales de Salburua(Fig. 9) and Armentia(Fig. 10). They play the role of core elements in the ecological network, embracing the water network. They dialogue either with the green and agricultural belt, or with the system of open spaces that gives access to the heritage sites in the city. They also reveal the countryside landscape and rethink the communities’ relationship with the edges of the city and its riverside landscapes.

As in the Olmsted’s strategies, water, the“sapphire necklace”, assumed a leading and resilient role in the design of this marginal landscape, as it helped structure these parks system technically and aesthetically. It promoted the physical and ecological connections in territory.

2.2 Rethinking Marginal Territories: The Democratic Dimension

At Vitoria-Gastiez, the democratic dimension of the green-blue space system proposed by Olmsted is created not only in these parks but also in the walkable and cyclable green routes that give the city user more opportunity to discover all these spaces and their programs (Botanical Garden-Olarizu, Nature Interpretation Centre-Ataria, among others). One of the main objectives is to “promote public use compatible with green spaces, increase opportunities for leisure and recreation, increase accessibility and country-city connections, preserve the cultural heritage and traditional landscapes and increase a sense of identity and belonging”[14].

Innovating the Olmsted’s theory, the involvement of the community was reinforced from the beginning to the end of the project,through workshops, talks and exhibitions. Practices to raise awareness of the marginal landscape’s green infrastructure network and the role of its blue-green space were carried out, with planting campaigns in project areas, programs such as“Adopt a tree” or the construction of family gardens and urban and school gardens. Other ways of raising awareness are the elaboration of a biodiversity inventory, as well as guided or free tours by bicycle or on foot that invite the community to see the margins.

3 Emeralds and Sapphires from Its Margins: The Local Case of the Zadorra Park Project

Reconsidering the Olmsted’s theory and incorporating the Theory of Landscape Ecology,green infrastructure is defined based on the benefit of the green and blue system as whole, but each element has its own importance. Zadorra is the main river in the Municipality of Vitoria-Gasteiz,and regionally it is part of the European Network of Protected Natural Areas (Natura 2000), due to its high concentration of biodiversity. Located in the northern region of the territory, its 13 km-long of the linear park along the river limits the expansion of the city to the north, composing its green belt. So far, only two sections have been executed.

3.1 Connecting Urban with Rural Marginal Landscapes in Different Scales: Agricultural Areas and Waterside

Greenways, bike paths and trails connect the park with the surroundings, mainly with the agricultural areas in the region. The project seeks to the transition from urban to rural landscapes,highlighting the role of the green open space system, from the green belt, especially the agrarian areas of high ecological value and historical and artistic significance.

The foodscape and the sounds of the water gain prominence in an organic design, steeped in naturalistic principles, with the use of resilient native species. Minimal elements invite the user to see how the vegetation is structured and these markers require little maintenance. The choice of plant typology is also conditioned by the amount of water present. The area suffers from heavy flooding, so a sustainable drainage system was proposed to optimize drainage performance,recovering Olmsted’s practices.

3.2 The Wildness of the Margins: Obsolete Areas and Less Valued Plants

Olmsted artificially created a wild aesthetic in the landscape, sustaining that wildness could be incorporated in the urban skyline to bring the community closer to nature, inviting users to perceive the landscape democratically[3-4]. At Vitoria-Gastiez the system of blue-green spaces also appears as a way of rethinking the marginalized,degraded and unoccupied areas of the territory,through contemporary ecological restoration, with the use of native species, creating different habitats and improving resilience and biodiversity, as well as the gradual transition in the interactions between humans and nature-culture (Fig. 11).

This concept has been applied to the design of the city’s ecological and sociocultural network,with a more organic vegetation physiognomy that is more engaged in the dynamics of the place, easier to manage and recognized by the community. This presents an experience with nature that gray and overbuilt cities are losing, and which Olmsted, in a different time and under different conditions, also fought to recover and value.

Everything on the margins is involved:agricultural areas, the waterside, obsolete areas and less valued plants. The marginal landscape is the protagonist, and it connects physically, ecologically and aesthetically with the place. Beyond this multiscale methodological of GI proposal for planning and design from the green belt to the park that rethink Olmsted theory nowadays, the different communities are invited to be part of and fight for their landscape[20].

4 Conclusion

Reconsidering Olmsted’s theory of the Emerald Necklace is fundamental to rethinking the landscape as the infrastructure of urban sustainable development, especially as we address the impacts of climate change and lack of biodiversity. Within this context, the system of green-blue open spaces are defined in green infrastructure strategies and projects, articulating the different dimensions of landscape on multiple scales.

When establishing methodological strategies that start from the first readings of the project,this multiscale dimension is observed. There is an effort to understand the territory on many scales(ecological, aesthetic, social and cultural values),defined in maps and syntheses, which are then translated into the form of a project.

The holistic design of the infrastructure of the landscape of Vitoria-Gasteiz is generally guided by the premises of the Theory of Landscape Ecology, paying special attention to the promotion of biodiversity, through physical and ecological connectivity, seeking to contribute to the reduction of the fragmentation of green areas in the territory.In this way, it develops the understanding of the ecological network composed of cores, nodes and connectors elements. Here, the elements of the green and blue space system were identified and organized in cores, nodes and connectors, following their ecological contribution in the network, valuing appreciation of its “emeralds”, or green areas, and its “sapphires”, the bodies of water.

At the local scale, the idea was to use ecological restoration, to bring nature and humans closer, with native species and Nature-based Solutions. This brings a contemporary perspective to Olmsted’s idea of joining the wild to the city.Creating an artificial structure based on Naturebased Solutions along with today’s technology, it is possible to invite the community to perceive and transform their marginal landscape, guided by water. Special attention is given, as it was by Olmsted, to providing technical but also artistic solutions for the marginal riverside landscape. As in the Emerald Necklace in Boston, in Vitoria-Gastiez the green-blue space system pays special attention to the contribution of the margin to the sapphire and emerald of the territory, valorizing the already existing green and agriculture belt.

Thinking about the landscape of cities from the standpoint of their marginal landscape also allows for greater contemporary articulation between urban and rural areas, revising the reduction of productive landscapes in the territory and the understanding of rural areas as places of food production and no longer in contact with nature. The productive landscape is understood and incorporated more effectively and at different scales, for example giving parks great views to agricultural areas, and incorporating rural trails,urban gardens and family gardens.

This is an important contribution to rethinking the traditional planning and design practices nowadays, making the marginal landscape a driver of strategies and their translation in terms of urban planning and design. The marginal landscape here is fundamental in the structuring of the green,agricultural belt, the blue network, and the other green axes that physically and ecologically connect the system of green and blue spaces. The ecological and sociocultural dimensions are jointly incorporated in their decision-making about the future of the region, and a lot of work is done to raise the awareness of the communities about their landscape,for example, with walkscapes and a campaign to adopt trees. The community is not only invited to perceive but also to be part of the landscape, to guarantee its right to it, recovering the democratic values of the park propounded by Olmsted.

It should be remembered that 29% of the urban population currently live in slums[21], and the majority live on the outskirts of cities, mostly under very different conditions from Vitoria-Gastiez, lacking urban infrastructure and guarantee of equitable rights. In parallel, the outskirts are generally areas of environmental interest that theParis Agreementand theConvention on Biological Diversityare trying to protect. Therefore, this experience can provide inspiration to other countries in rethinking their margins with a place-based methodology, updating and rethinking Olmsted’s theory today.

Sources of Figures:

Fig. 1, 6~11©Camila Gomes Sant’Anna; Fig. 2~5©Caroline Fernandes, adapted from https://www.vitoriagasteiz.org/j34-01w/catalogo/portada?idioma=es.

(Editor / LI Qingqing)