A Common Thread

An embroider’s commitment to reviving ethnic minority culture By Li Xiaoyang

With the needle moving carefully in her hand, images in Chen Yunzhen’s mind’s eye take shape across a piece of fabric, in colors across the spectrum. As if by magic, the two-meter long plain cloth is transformed into a thing of beauty, embellished with azalea and pomegranate patterns. Fifty-something Chen, from Beichuan Qiang Autonomous County in Sichuan Province, is a master of the embroidery of the Qiang ethnic group and has been working on this piece of art for months.

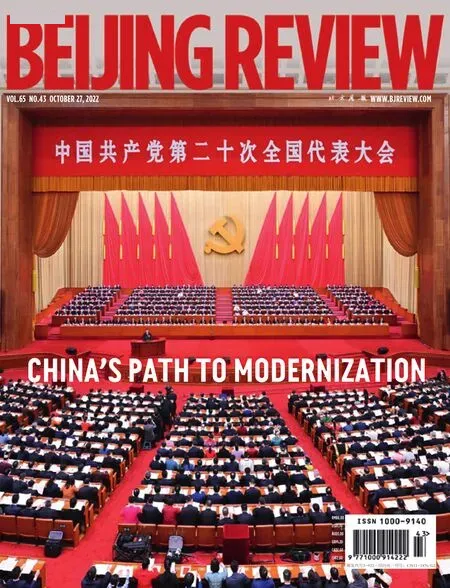

Chen, who joined the Communist Party of China(CPC) in 2000, has been taking the lead in carrying forward the technique, which has been recognized as a form of intangible cultural heritage at the local and national levels. Her efforts have been recognized, and she was elected as a delegate to represent Sichuan at the 20th CPC National Congress, held in Beijing from October 16 to 22. She brought the piece to Beijing to showcase it. “For Chinese people, azaleas and pomegranates are auspicious symbols, which respectively suggest prosperity and ethnic unity,” Chen told.

Qiang embroidery boasts a long and rich history,dating back to the Han Dynasty (202 B.C.-A.D. 220)when it was adopted for use on clothing. It makes use of many kinds of stitches, including crossed, flat and chain ones. The densely stitched embroidery protects the clothes from wearing out. The Qiang people adore nature and believe that all things have a soul, so they embroider plants and animals on clothing. Flowers,grasses, fruits, vegetables, animals and human figures are used as inspiration for the craft’s most common patterns. This type of embroidery features a bold use of brilliant colors. In 2008, Qiang embroidery was included on the national list of intangible cultural heritage.

Qiang embroidery is usually practiced by women.According to Chen, a pair of embroidered shoes can take as long as 10 days to produce, making the practice a test of both skill and patience.

Chen is working to preserve and revitalize Qiang embroidery, and is sharing the technique with others in her local area.

Reviving the skills

When Chen was a girl, she often saw her mother and grandmother embroidering clothes. They began teaching her the technique when she was 9.

As the local tourism industry began to develop, Chen discovered many tourists were interested in Qiang embroidery products. She decided to promote the embroidery of Beichuan as a brand to attract more tourists. Many local women, encouraged by Chen, began to earn their living through Qiang embroidery.

When the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake struck the region, many Qiang embroidery facilities were destroyed and some embroiderers lost their lives. As part of her efforts to stop the endangered technique from disappearing altogether, Chen began visiting the surrounding regions, where the Qiang people gathered following the earthquake,to teach embroidery. “As a member of the Qiang ethnic group, I feel obligated to carry it forward; otherwise, it will wither away and exist only in our memories,” Chen said.

Just as the once devastated region has today regained its vitality, the technique,too, has been revived. In 2012, Chen was designated as a provincial-level inheritor of Qiang embroidery. In 2014, she established a Qiang embroidery workshop that has since provided free training to over 20,000 people. Over 500 local embroiderers,including full-timers and part-timers, make a living through the workshop, including many who were left disabled following the earthquake. Skillful part-timers can earn up to 20,000 yuan ($2,780) every year from embroidery, while full-time employees can earn over 40,000 yuan ($5,536).

Chen Yunzhen (center) works with her partners in Beichuan Qiang Autonomous County, Sichuan Province, in July

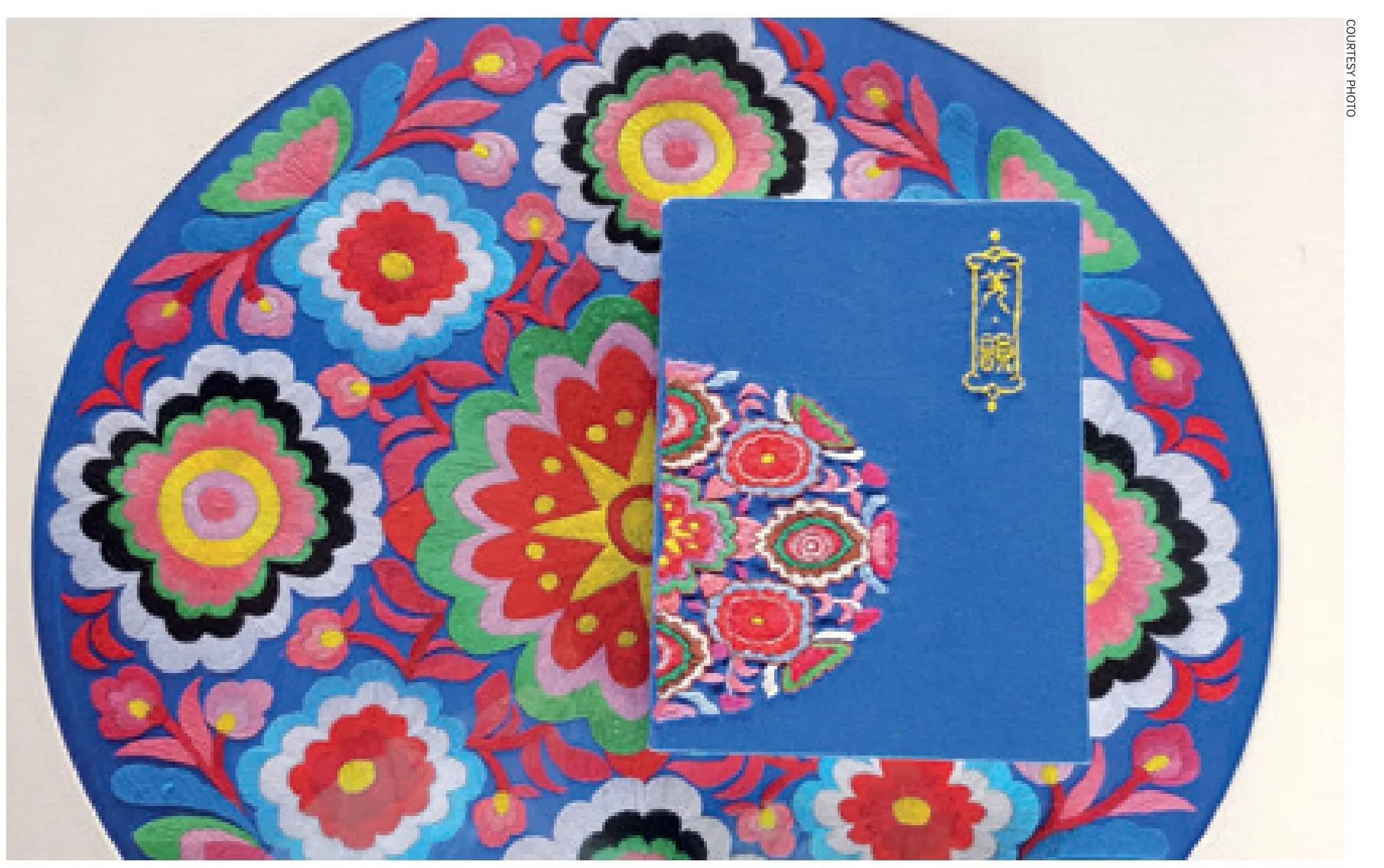

A notebook decorated with Qiang embroidery patterns designed by Chen Yunzhen’s workshop

Chen also established an exhibition hall to showcase Qiang embroidery works,promote sales and invite tourists to try the technique. According to Chen, products like belts are sold for approximately 200 yuan ($27.8) each. Embroiderers can make smaller accessories at a rate of around a dozen a day and these can be sold for around 10 yuan ($1.39) each.

Zhao Yiqiong, a villager in Beichuan’s Leigu Township, lost her legs in the 2008 earthquake. Zhao, who used to be a businesswoman, was unable to continue her career. After her husband passed away due to illness, she lived a hard life until she began learning Qiang embroidery from Chen in 2015. Now she makes embroidery at home for Chen’s workshop, starting a new career.

In recent years, the government of Beichuan has been focusing on encouraging local women to learn Qiang embroidery as a way of earning a living and improving their lives. It has provided preferential policies for embroiderers, supported them in starting their own businesses and promoted the development of industrial chains for Qiang embroidery.

According to the Beichuan Bureau of Culture, Broadcast, Television and Tourism,the government has provided training for local people, through which many have become professional Qiang embroiderers. The county now has 20 Qiang embroidery enterprises, with more than 500 full-time and over 11,000 part-time employees. Since 2012, the net revenue of the companies has totaled around 7 million yuan ($983,500)per year, improving the annual income of the people involved by an average of 6,000 yuan ($843).

New impetus

In 2015, Chen’s workshop faced a bottleneck caused by a glut of similar products. To breathe new life into Qiang embroidery, Chen has continued to keep an open mind, introducing new products like personal accessories, notebooks and bags in addition to the traditional clothes, belts and hats. The works have been sold at offline exhibitions and online stores,and have also reached several European countries and the United States.

In August, Chen signed an agreement with Chinese sportswear company Li-Ning to add handmade Qiang embroidery to its products. Under the agreement, Chen received an initial order for 2,000 items of clothing, with more cooperation already in the pipeline, which is expected to further boost the incomes of the embroiderers.

After graduating from university, Chen’s two daughters returned to their hometown to help support her efforts. With a youthful sense of innovation, the two have combined metalwork and Qiang embroidery to create earrings, rings and necklaces that are popular among young consumers. They are also considering live-streaming to promote their handmade products.

According to Chen, the Qiang people do not have a written language, so Qiang embroidery must be well preserved and developed as part of efforts to sustain its culture. In recent years, Chen has also been introducing the technique in local colleges through lectures.

For Chen, Qiang embroidery is much more than a piece of art to appreciate. “If you allow it to impart its real value, it will improve more people’s lives and drive rural revitalization,” she said. BR