Does educational intervention change knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding pharmacovigilance among nursing officers in Central lndia? An interventional study

Chaitali Ashish CHINDHALORE, Ganesh Natthuji DAKHALE, Ashish Vijay GUPTA

Department of Pharmacology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Nagpur, Maharashtra, India

ABSTRACT Objectives: To evaluate the impact of educational intervention on knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) regarding pharmacovigilance (PV) and adverse drug reaction (ADR) reporting among nursing officers.Materials and Methods: A pre- and post-single-arm interventional study was conducted at All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), Nagpur from May 2021 to October 2021 among 48 nursing officers. Data related to KAP were obtained through validated questionnaires before and after 3 months of educational intervention.Results: The mean knowledge score among nursing officers significantly improved from 11.05 ± 3.09 to 16.77 ± 2.07 after training session (P < 0.001). The mean score regarding attitude was significantly upgraded from 21.16 ± 5.6 to 23.79 ± 2.97 (P < 0.001). At baseline, the mean practice score was poor (2.41 ± 2.89), which was improved after training session, but the difference is not significant.Conclusion: Educational intervention had a significant impact on knowledge and attitude toward ADR reporting. The practice of detecting and reporting an ADR to the treating consultant is improved, but it is not transformed into reporting an ADR to the PV center to a significant extent. Hence, it is recommended to streamline ADR reporting process by implementing such training modules more frequently.

Keywords: Adverse drug reaction, attitude, knowledge, nursing staff, pharmacovigilance, practice

INTRODUCTION

Monitoring the safety of medication given to a patient is an important part of clinical practice. The word pharmacovigilance (PV) is derived from the Greek word “pharmacon” meaning “drug” and the Latin word “vigilare” meaning “to keep awake or alert.” The World Health Organization (WHO) defines PV as ‘science and activities relating to detecting, assessing, understanding and preventing adverse effects or any other drug-related problems.’ PV encompasses the identification, quantification, and documentation of drug-related problems which are responsible for drug-related injuries.[1]India is the second most populous country in the world with over a million drug users. Currently, India ranks fourth in the world with 6000 licensed manufacturers and more than 6600 branded ingredients on the market.[2]A previous study finding revealed that adverse drug reactions (ADRs) accounted for 0.7% of hospitalization and were responsible for 1.8% of deaths among total hospital admission in addition to imparting a significant economic burden.[3]

In India, the Directorate General of Health Services under the aegis of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, unitedly with the Indian Pharmacopoeia Commission, Ghaziabad, launched a national PV program to protect patients’ health by ensuring drug safety.[4]A well-functioning PV system is vital if medicines are to be used safely. The effectiveness of a PV program depends on the knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) of health-care professionals (HCPs) who play a key role in patient care. Numerous studies explored PV-related KAP among medical practitioners across the globe. These studies suggested that there is a great need to create more awareness and training sessions to improve ADR reporting practices among the HCPs.[5,6]Various studies revealed that education and training programs can improve the KAP of HCPs regarding PV and ADR reporting.[7,8]However, most studies have examined the effect of interventions on the knowledge and attitude domain.[9]Very few studies have examined the effect on ADR reporting practices.[10]

In any health system, nursing officers are involved in direct patient care. Although PV is a part of undergraduate nursing curriculum at many universities, previous studies on PV revealed underreporting of ADR by nursing officers. Lack of awareness and negligence of nursing staff is one of the reasons for underreporting of ADR.[11-13]Findings from previous researches[9,11,12]strongly recommend educational training to improve PV-related KAP. The current study is designed to assess the impact of formal PV-related education interventions on KAP related to PV that will be useful in designing a PV training modules as a part of in-service training program for nursing officers to strengthen PV program of India (PvPI). Hence, the present study was planned to assess the impact of structured educational intervention on KAP of nursing officers regarding PV and ADR reporting using a validated questionnaire.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and setting

A pre-post single-arm intervention study is adopted. The study was conducted at a newly established tertiary institute of National Importance. Currently, it is a 350-bed institute with 28 departments including super-specialty which provide comprehensive health care to patients.

Participants

The study was conducted among nursing officers employed in the institute. All nursing officers working in the institute were eligible. The study was conducted from May 2021 to October 2021.

Sample size was calculated based on changes in participants’ perception score as the main variance with a significance level (α) of 5% and power 90%. In a previous study,[11]the mean perception score significantly improved from 33.6 (standard deviation [SD] = 5.4) to 37.0 (SD = 3.1). Based on these statistics, sample size was calculated using Open Epi: Open Source Epidemiologic Statistics for Public Health, version 3.01 Atlanta, GA, USA. The calculated sample size was 52 considering 20% dropout rate.

Educational intervention

Training session regarding PV was scheduled for all on-duty nursing officers. From those present for training sessions, we enrolled 52 participants using a simple randomization method after explaining study’s purpose. Before the beginning of each session, participants were requested to fill out the study questionnaire and handed it over to investigators. Time allotted for filling questionnaire was 15 min. It represents baseline preintervention data. The educational intervention was conducted by a coordinator and a deputy coordinator for PvPI as a 2-h session which consisted of PowerPoint presentations. This session covered definition of PV, types of ADR, how to identify ADR, how to report ADR, where to report ADR, causality analysis of ADR, and role of nursing officers in PV. Didactic lecture was followed by an interactive discussion and Q/A session. It was followed by hands-on training for filling ADR form. The demonstration of VigiFlow will be given to all the participants, which is a web-based individual case safety report management system, used for recording, processing, and sharing reports of adverse effects. It is accessible for practice by national PV centers of the WHO program.

Following an intervention session, the same questionnaire was given to participants after 3 months to assess long-term effect on knowledge and attitude regarding PV among them and also to evaluate the effect on practice of ADR reporting. ADRs reported by nursing officers after session were verified from ADR form submitted to PV committee which included reporter’s detail.

Outcome measures

1. Change in individual question score regarding KAP after 3 months of educational intervention

2. Change in the mean KAP score after 3 months of educational intervention.

Study instrument

A predesigned structured questionnaire adapted from previous studies[9-11]was slightly modified to suit our hospital setting and was subjected to a review and validation process. Face validity of the questionnaire was evaluated in terms of readability, feasibility, layout, style, and clarity of wording. Face validity was done by five subject experts who are not part of the study. Changes advised by experts related to readability and clarity of wording were incorporated into the questionnaire. For content validity, the questionnaire was sent to an expert in PV. Content validity was assessed by calculating content validity index (CVI). CVI for scale (S-CVI/Ave) was calculated by taking an average of the I-CVIs for all items on the scale. S-CVI/Ave was 0.84. Reliability was tested by sharing questionnaires at different periods with the same subset of responders. The score was calculated and compared using Pearson’s correlation coefficient formula. Pearson’s correlation coefficient value was 0.72. Cronbach’s alpha value was calculated to measure internal consistency, which was found to be 0.78 signifying good internal consistency.

The final version of questionnaire had four sections. Section A included demographic parameters. Section B comprised 10 questions designated to evaluate nursing officers’ knowledge about PV. Section C contained 5 questions linked to attitude and section D comprised 5 questions about practice of PV among nursing officers.

For section B, one point was given for each correct answer and “0” for each wrong answer except questions no. 1, 3, and 7. For these three questions, one point was allotted for each correct option. Hence, for section B, the maximum score was 19.

Regarding participants’ attitude, the scoring system used was as follows: strongly agree = 5, agree = 4, neutral = 3, disagree = 2, and strongly disagree = 1. The maximum score allotted was 25. For practice section, “No” reply carried “0” mark, and frequency of practice indicated score. For example, If a nursing officer reported 5 ADRs then his/her score was calculated as 5.

Statistical analysis

The data were expressed as mean ± SD or percentage wherever applicable. The data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 9.0., manufactured by GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA, 92108. Pairedt-test was used to evaluate differences in scores for KAP. Categorical data were analyzed by theChi-square test.P< 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical consideration

The study was conducted after seeking approval from the research cell and institutional ethics committee (IEC/Pharmac/2021/195 Date 22/02/2021). The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki by the department of pharmacology, accredited ADR (AMC) monitoring center under PvPI. Written informed consent was obtained from those who were willing to participate and was assured that their participation in this study was voluntary and they have a right to quit the study at any time. Furthermore, they were informed that their identity and responses had been kept confidential and analyzed only as a part of cohort.

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics of participants

Out of 52 participants, 48 submitted postintervention questionnaires. Hence, the data were analyzed depending on responses from 48 participants. Among them, 12 (25%) were male and 36 (75%) were female. The mean age of participants was 25.6 ± 2.2 years. The majority of participants had professional experience of fewer than 5 years (93.75%).

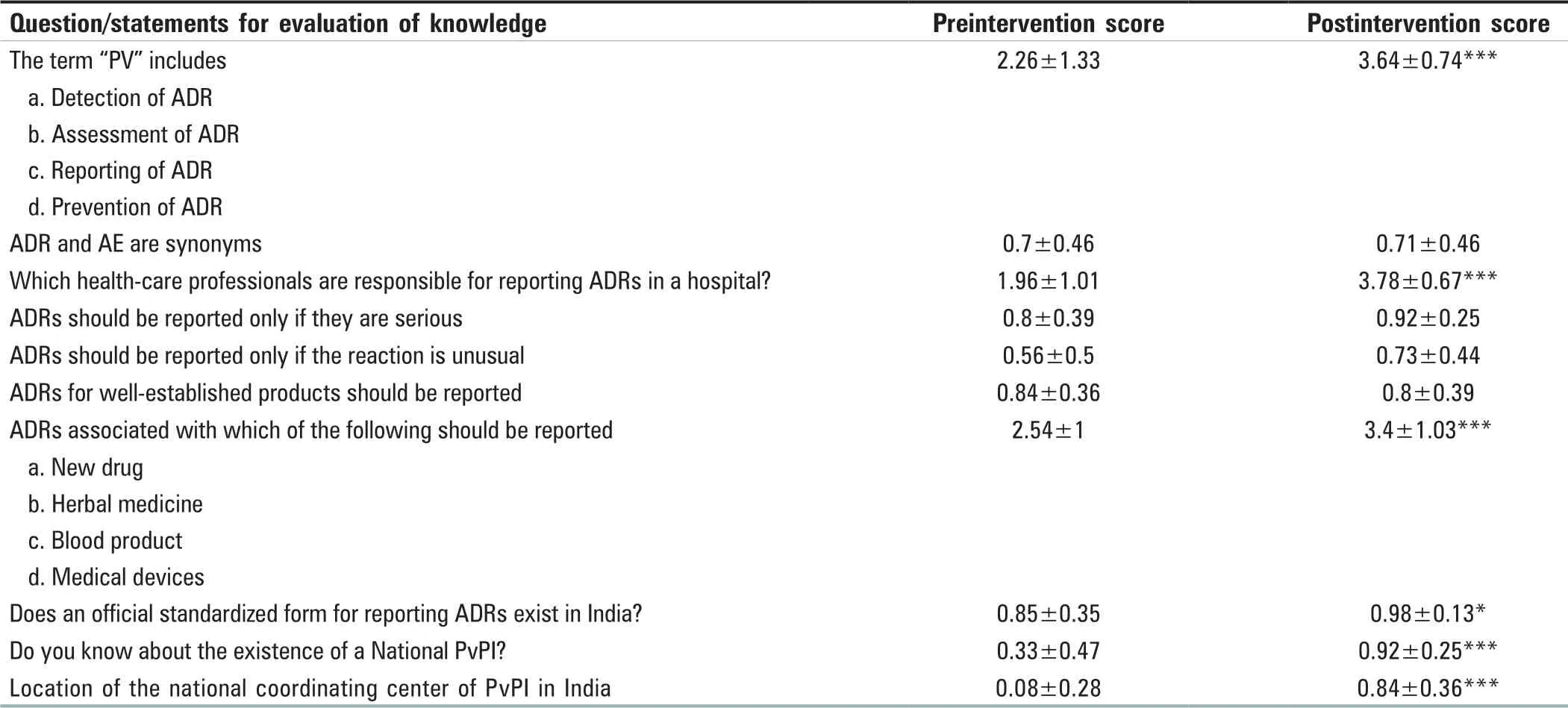

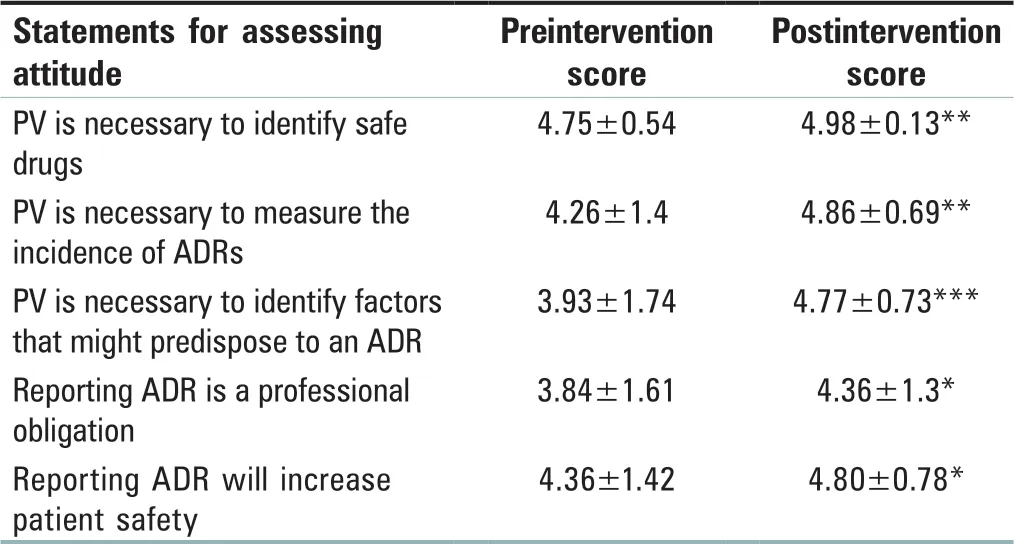

Knowledge of PV was assessed through 10 questions related to PV. There was a significant improvement in knowledge score after intervention, especially knowledge regarding definition, who can report, and the existence of PvPI and NCC for PvPI [Table 1]. Participants’ attitude toward ADR reporting was good, which improved further postintervention [Table 2]. Observation or detection of an ADR in patients was significantly improved after the intervention. Before the session, 50% nursing officers observed ADR in patients, which improved after the session to 93.75%. Reporting of observed ADR to treating consultants also improved significantly after intervention from 47.91% to 60.41%. However, reporting of an ADR to the PV center was not significantly improved. Although comparatively more nursing officers filled ADR forms after training sessions, change was not significant [Table 3].

Table 1: Comparison of knowledge score regarding pharmacovigilance and adverse drug reaction reporting among nursing officers (n=48)

Table 2: Nursing officer’s attitude toward pharmacovigilance and adverse drug reactions reporting (n=48)

Table 3: Practice regarding pharmacovigilance and adverse drug reaction reporting among nursing officers (n=48)

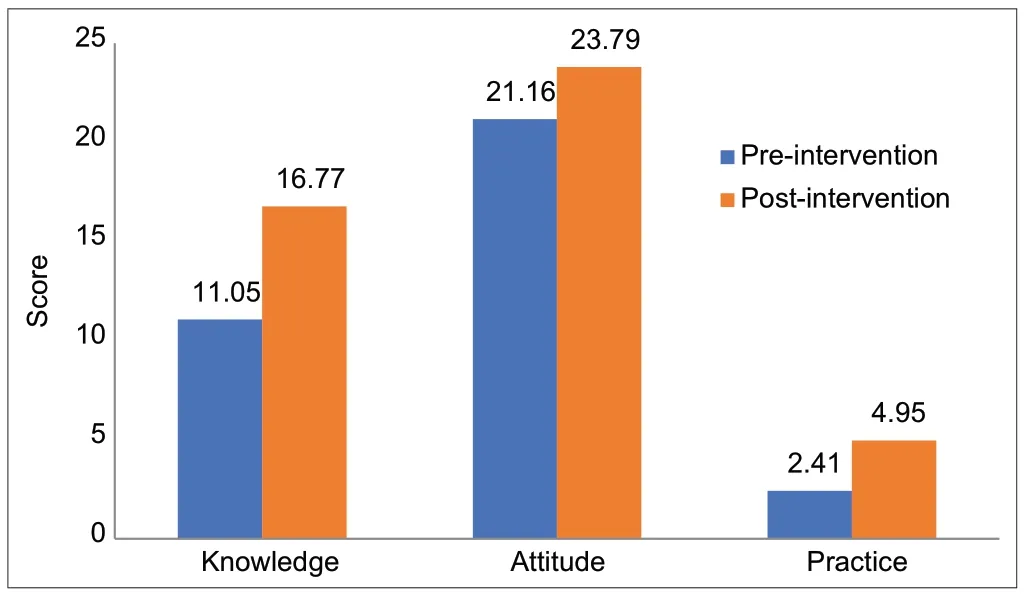

The difference in the mean score for knowledge, attitude, and practice

The overall knowledge score among nursing officers significantly improved from 11.05 ± 3.09 to 16.77 ± 2.07 after a training session. The mean score regarding attitude was significantly changed from 21.16 ± 5.6 and 23.79 ± 2.97. At baseline, the mean practice score was poor (2.41 ± 2.89), which was improved after the training session, but the difference was not statistically significant [Figure 1].

Figure 1: Pre- and postintervention comparison of mean score of knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding PV among nursing officers (n = 48). PV: Pharmacovigilance

DISCUSSION

Spontaneous ADR reporting is an imperative tool in detecting and reporting ADRs to improve patient safety.[14]For that, it is essential to conduct comprehensive studies to explore and evaluate health-care providers’ roles and contributions in activities related to PV. Various studies evaluated KAP regarding PV among HCPs, but very few studies gaged the impact of training sessions on these parameters, especially practice related to PV and ADR reporting.[9,10,15]Nursing officers plays a key role in patient care. Most of the time, they are the first to be informed by the patient or caretaker regarding ADR. Hence, the present study assessed baseline KAP regarding PV and ADR reporting, especially among nursing officers using a validated questionnaire and assessed the impact of training sessions on these parameters.

Female preponderance was observed in the present study. In our institute, majority of nursing officers are female. More inclination of womens towards nursing as a profession might be the probable reason for these findings as previously reported.[16]Most of the participants were found to be in the age group of 21-30 years with a mean age of 25.6 years, which is similar to the previous study[9]with work experience between 1 and 5 years. A previous research has proven that the mean knowledge and attitude score depends on years of experience.[17]

In the current study, participants had sufficient basic knowledge that was significantly improved after the educational intervention. Knowledge about who can report and what should be reported was significantly improved after a training session. Initially, only 8.33% of participants were able to answer the correct location of the national coordinating center of PvPI in India. After a training session, 81% of participants responded positively. Previous studies also revealed that educational intervention improved knowledge scores among health professionals.[8,10,14,18,19]Studies have proven that participants who have sufficient knowledge of PV have a positive attitude toward ADR reporting and will contribute to a better ADR reporting practice.[17]On contrary, a study from Northeast Ethiopia stated poor knowledge regarding PV among health professionals.[20]

Existing study findings showed that the majority of nursing officers had a positive attitude toward PV, which was improved further after a training session. Various studies confirmed favorable attitude of HCPs toward PV.[13,21,22]Attitude toward ADR reporting as a professional obligation was significantly improved after the session. It has significance since it is more related to moral bindings and ethical issues. Shresthaet al.[9]also stated that educational intervention is a key component to improve attitude scores among health professionals.

The current study observed poor practice of reporting ADR. Prior to training, 50% of participants had seen ADR in patients and 47.91% of nursing officers had reported ADR to treating consultants. However, only 5 nursing officers reported ADR to PV center. Probable reasons as stated by participants are more workload, internet issues, lack of confidence, and lack of time. In a study by Hanafiet al.[13]from Tehran, 91% of nursing staff never reported an ADR. Previous studies’ findings stated that although knowledge and attitude of health professionals toward PV were satisfactory, in reality, very few HCPs reported ADR to treating consultants or PV centers.[12,13]

A study by AlShammari and Almoslem[23]from Saudi Arabia stated that HCP’s perception that the report might be incorrect (46%) and lack of time to report ADRs (44%) was the reason for underreporting. In a study by Jnaneswaret al. from India,[17]main barriers to reporting ADR were lack of knowledge, confidence, and fear of adverse remarks on performance report. Whereas, in a study by Al Rabayahet al. from Jordan,[24]lack of training regarding reporting of ADR and lack of time were the most common barriers.

In the present study, significantly more ADR was observed and reported to treating consultants by nursing officers after educational intervention, which is a welcoming sign.

However, reporting it to the PV center has not changed much. On contrary, educational intervention resulted in improved ADR reporting in previous studies by Ganesanet al.[10]and Aguet al.[25]This issue needs to be addressed. It is necessary to find loopholes in the existing ADR reporting process and need to resolve them.

We assessed the impact of educational intervention after 3-month periods, which is quite a short span to bring about significant change in practice. The study was a single-center study conducted on nursing officers only. Similar kinds of studies should be conducted in other HCPs to explore these parameters. Measures such as regular sensitization sessions, reminders in the form of SMS or flyers, interprofessional communication and collaborations, an online reporting facility, or inclusion of ADR form along with case sheet may improve the spontaneous reporting of ADRs at the institute level.

CONCLUSION

Finally, to conclude, structured educational training module significantly improved knowledge and attitude toward PV among nursing officers. The practice of detecting and reporting an ADR to the treating consultant is improved, but it is not transformed into reporting an ADR to the PV center on a significant scale. Hence, to improve ADR reporting practices further, there is a need to conduct such structured training sessions more frequently and to streamline the ADR reporting process at each step to make it more approachable.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Journal of Integrative Nursing2022年3期

Journal of Integrative Nursing2022年3期

- Journal of Integrative Nursing的其它文章

- Nursing perspective of Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Gout with lntegrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine

- Role of community health nurse in the prevention of elderly dehydration: A mini-review

- Technology-based psychosocial support for adolescent survivors of leukemia: An example intervention for nurse specialists

- Faculty of health sciences students’ knowledge and attitudes toward coronavirus disease 2019 during the first wave of the pandemic: A cross-sectional survey

- Practice and patronage of traditional bonesetting in Ondo State, Nigeria

- Nurses and nursing students’ knowledge regarding blood transfusion: A comparative cross-sectional study