Understanding the Importance and Challenges of the “Blue Pacific” to Pacific Islanders

Sue Farran

Abstract:The importance of the oceans is a topic of increasing significance to a wide range of sectoral actors from environmentalists,marine scientists,security analysts,climate change activists,public and private fisheries organisations and legal scholars.The oceans are also areas in which competing powers seek to achieve dominance.The Pacific is one of those oceans.Pacific islanders reached these islands by navigating the vast ocean;most live within a few kilometres of the coast;the ocean is associated with their stories of origin,their ancestors and is essential to their survival.But it also poses a number of ecological risks,either directly,or through the interventions of others.Rising seas as a result of climate change are one example.Depleting stocks of fish due to over-fishing and illegal,unreported and unregulated fishing are another.Marine pollution from a number of sources poses further risks,as do the potential environmental impacts of deepsea mining.Within the context of the long-standing relationship of Pacific islanders with the oceans that surround them this paper examines some of the threats they face,the strategies that are being adopted to secure sustainable futures for the next generations of islanders and the challenges that are presented by patchy and often imperfect legal frameworks.

Key Words:Pacific island countries;Marine pollution;Rising seas;Illegal,unreported and unregulated fishing;Deep-sea mining;Legal challenges

I.Introduction

To understand the importance of the “Blue Pacific” to the people of the Pacific it is useful to have some contextual understanding.The people of the Pacific navigated across the ocean in canoes to reach the islands they now inhabit.Pacific island Countries (PICs) have a great deal more sea than land -with the exception of Papua New Guinea,which has a much larger land mass and greater population.The exclusive economic zones (EEZs) of PICs representing 74% of the Western and Central Pacific Ocean.The ratio of land to sea is indicated in Table 1.Most people live at or near the coast which means that Pacific islands are dependent on the ocean and vulnerable to its weather conditions.Marine resources are important as a source of food,for employment at different levels,for generating government revenue (for example through fisheries),while coastal areas are significant for supporting economic development (such as tourism).To sustain these sectors requires healthy oceans and marine ecosystems.Many Pacific islanders are connected by local and inter-island sea-transport.More recently Pacific island governments have become aware that the sources of the sea-bed may also offer a tempting economic solution to struggling economies,because of the demand that the developed world has for minerals that can be mined.

The many languages,cultures and traditions and histories of the Pacific island people create huge diversity across the region,but there are also shared concerns and challenges.As the former Secretary General of the Pacific Islands Forum has said:

Ninety-eight per cent of the area occupied by Pacific Island countries and territories is ocean ...The Pacific Ocean is at the heart of our cultures and we depend on it for food,income,employment,transport and economic development ...The ocean unites and divides us.It connects and separates us,it sustains us and,at the same time,can be a threat to our very existence.2Dame Meg Taylor,A Sea of Islands:How a Regional Group of Pacific States Is Working to Achieve SDG 14,UN website (May 2017),https://www.un.org/en/chronicle/article/seaislands-how-regional-group-pacific-states-working-achieve-sdg-14.

This paper picks up this last point:the threat of the ocean to the continued existence of Pacific island people.It focuses on four ecological risks:marine pollution,rising seas,illegal,unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing,and deep-sea mining.These risks are closely linked to climate change because the activities involved contribute to,rather than mitigate carbon emissions;destroy natural resources that might be used to address climate change;and increase the vulnerabilities of those already most vulnerable to climate change.These risks also pose threats to achievingSustainable Development Goalsparticularly those relating to the right to health,to food security,to fresh water,to life below the sea and climate action.Highlighting these issues raises the question whether the international community’s determination to “leave no one behind” can realistically be achieved in the face of climate change.In particular,this paper asks whether the regional and international legal framework is fit for purpose for securing the “Blue Pacific” for present and future generations of Pacific islanders?

II.Marine Pollution

Ocean pollution in the Pacific includes man-made pollution especially plastic pollution but also pollution from ships,from disintegrating ship and air wrecks -a legacy of World War II,in particular,and the potential pollution risks posed by the trans-shipment of hazardous and nuclear waste.This pollution threatens the bio-diversity of the ocean and its resources,including fish and therefore the health and sustainable development of Pacific islanders.While pollution,especially to estuaries and coastal areas,is also caused by terrestrial activities,notably mining,logging and coastal tourism development,the focus here is on plastic pollution,pollution from wrecks and the potential threat of pollution from the transhipment and/or dumping of hazardous waste.

A.Plastic Pollution

It is estimated that 50-80% of marine pollution is plastic.Marine debris,largely comprised of plastics,poses a serious threat to marine life in the Pacific.3Ana Markic &Mark J.Costello,Plastic Ingestion by Fish in the South Pacific,SPREP website,https://www.sprep.org/attachments/2016SM27/official/WP_9.3.2.Att.1_-__Plastic_ingestion_by_fish_in_the_South_Pacific_-_Samoa_results.pdfFish ingest microscopic plastics either directly or indirectly,which then pass into the food chain.As fish is a mainstay of food security and protein provision in the Pacific this raises real health risks to Pacific people and threatens the health of fish populations.This is turn jeopardises the sustainability of fish stocks which are not only needed for food but are an important income stream at local and national levels.Plastic breaks down to release methane and other carbon contributing gases thereby contributing to global warming.By 2050 it is estimated that plastic will contribute 13% of total carbon emissions.4Ketan Joshi,Plastics:A Carbon Copy of the Climate Crisis,ClientEarth (16 Feb 2021),https://www.clientearth.org/latest/latest-updates/stories/plastics-a-carbon-copy-of-theclimate-crisis/.

While much of the plastic pollution of the Pacific Ocean comes from elsewhere,carried on currents,Pacific islands themselves struggle to cope with plastic waste.This is due to a combination of factors,notably lack of resources and high costs leading to poor waste management and very little recycling which is aggravated by a marked shift away from subsistence economies to greater disposable income and associated increased demand for consumer goods,many of which contain plastics.Most waste goes into landfill,and with very limited land masses on many islands unless that waste is quickly bio-degradable there is the risk that it finds its way into watercourses,is blown away from landfills sites or if,left in situ,takes a long period to break down.While there has been a Chinese initiative to collect and ship plastic waste back to China for re-processing,this does not encompass all plastic waste.If the Pacific is to become plastic-free then consideration has to be given to the types of packaging used for products which are imported into these countries -including water in those areas where fresh-water is at a premium.This places an onus on manufacturers of consumer goods and those commercial organizations which benefit from trade exports to the Pacific region.

Pacific island governments,civil society,churches and schools are taking steps to counter plastic pollution.Legislation prohibiting single use plastic is now widespread,while the shift to more traditional and reusable containers is providing opportunities to the handicraft sector,particularly women.Meanwhile,there are several volunteer organisations promoting beach and street clean-ups.The challenges however are complex.Urban migration -often into peri-urban areas where there is little scope to cultivate traditional food crops,increases in population density,and an increase in consumer spending,all contribute to more waste,including plastic waste.Relying on corporate social and environmental responsibility -which is often voluntary and not mandatory -is not sufficient.There also needs to be greater effort to develop technological solutions appropriate to island economies for dealing with plastic waste.This requires knowledge transfer and resource development at scale.

Slowly the international community is realising the need to reach international consensus around reducing the plastic footprint of the manufacturing sector.There is increasing momentum to agree an international and legally binding treaty mandating targets to reduce plastic pollution.In February 2022,the World Economic Forum held a meeting on “Building Momentum Towards A Global Treaty on Plastic Pollution” and the United Nations Environment Assembly,held shortly afterwards,agreed to launch negotiations on a global agreement.The aim is to conclude negotiations by 2024.Hailed as a “Paris Agreement on Plastics” it remains to be seen whether consensus can be reached and whether countries -especially in the developed world -will take adequate steps to meet targets.

B.Wreck Pollution

A second marine pollution risk is that of disintegrating wrecks.Many small States with maritime boundaries experience the problem of marine vessels colliding,being wrecked or causing pollution due to human or natural causes.While these incidents are not numerous,they can cause considerable local harm and concern.There are estimated to be over two hundred shipwrecks in the Pacific Ocean,5The combined number of wrecks in the region is hard to calculate.Michael Field writing in 2002 refers to a figure of ‘more than 1,000,but this includes those around Philippines and off the Australian coast.See Michael Field,World War II shipwrecks turning into Pacific environmental threat,ThingsAsian (15 Nov 2002),http://thingsasian.com/story/world-warii-shipwrecks-turning-pacific-environmental-threat.And more continue to be found.See for example the recent discovery of the wreck of USS Juneau off the Solomon Islands in March 2018.many of which were casualties of war in the Pacific,but some reflect a much earlier period of colonial encounter such as theSMS Eber,a German ship sent in 1887 to assist the German colonial enterprise in the Pacific.Damaged by a cyclone she sank at the edge of the harbour in Apia,Samoa with the loss of seventy-three crew.6The same cyclone sank three United States warships and one further German warship.Even earlier voyages are reflected in wrecks such as that of the Argo in the early 1800s,7The exact date is disputed.One of the survivors is reputed to have instigated the Sandalwood trade between Fiji and China after spending two years on Vanua Levu.off the south east coast of Fiji,and the Pandora -the ship sent to search for the Bounty mutineers,8Some of whom eventually settled on Pitcairn in the Pitcairn Islands.which was wrecked on the Great Barrier Reef off the east coast of Australia in 1791. A greater problem,however,is the legacy of the Pacific as a theatre of war in World War II.Some 13 million tonnes of shipping were destroyed in the four-year war.912 Pacific governments have mapped 3,852 Japanese and US ships sunk in the Pacific during world War II.See John Vidal,Causing A Stink:Second World War Wrecks Surface as A Threat to Pacific Environment,The Guardian,7 Feb 2004,at 3.3,700 war wrecks are registered globally.The Pacific is also home to one of the largest marine dumps of military vehicles and equipment.10It is estimated,for example,that in the seas off Million Dollar Point in Vanuatu,the American military dumped tons of equipment worth millions of dollars,rather than go to the expense of taking it back home after the end of the second world war and Pacific operations.American Aircraft were dumped off Kwajalein Atoll in Marshall Islands,and Truk (Chuuk) Lagoon in the Federated States of Micronesia is the site of wrecks of over 40 Japanese ships and 250 Japanese aircraft.

While early wrecks of ships built largely of wood broke up easily,later vessels constructed of iron and steel have taken longer to disintegrate and it is increasingly being recognised that as these vessels deteriorate the risk of pollution from fuels and sunken cargoes rises.Indeed,the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe published a paper in 2012 which stated that:“Shipwrecks,ocean acidification and the dumping of waste into oceans are among the biggest sources of marine pollution.”11Parliamentary Assembly,The Environmental Impact of Sunken Shipwrecks,PACE website (9 Nov 2018),http://assembly.coe.int/nw/xml/XRef/Xref-XML2HTML-en.asp?fileid=18077&lang=en.It went on to state that “without maps charting these risks,no accurate assessment of the threat can be made.An inventory of potentially polluting wrecks was compiled by Environmental Research Consulting in 2004.This international marine shipwreck database has identified some 8,569 potentially polluting wrecks around the world.In the Pacific it is estimated for example,that there are 150 shipwrecks in Solomon Island waters as a result of the battle of Guadalcanal,270 in Papua New Guinea waters,200 in Marshall Islands and the Federated States of Micronesia.12Richard Lloyd Parry,Pacific Wrecks Are Ecological Timebombs,The Times,4 March 2004There are also dumps of military vehicles and equipment in the ocean (Vanuatu and Marshall Islands) and in Truk Lagoons (Truk Lagoon in Federated States of Micronesia is estimated to be the graveyard of 40 Japanese ships and 250 Japanese aircraft).

According to theSouth Pacific Regional Environment Program(SPREP),while the danger of damage from these wrecks is well known,only Fiji,Papua New Guinea,and Niue have the equipment to deal with marine spills.There are a number of international laws,13International law include the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea,the 1954 International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution of the Sea by Oil,the 1973 International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution From Ships and its 1978 Protocol.the most significant of which here is theNairobi International Convention of the Removal of Wrecks(namely “Nairobi Convention”)2007,which came into force on 14 April 2015.14Jhonnie Kern,Wreck Removal and the Nairobi convention -A Movement toward a Unified Framework?,Frontiers in Marine Science (25 Feb 2016),https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2016.00011/full.Not all PICs,however are parties to the NairobiConvention,notably those most affected by the Pacific theatre of war,such as Solomon Islands,Papua New Guinea and Federated States of Micronesia.15Only Marshall Islands and Niue has extended the Convention to their seas,although the convention is in force in Cook Islands (through extension by New Zealand),Nauru,Palau,Tonga and Tuvalu.Regional initiatives include:the 1981Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment and Coastal Area of the South East Pacific(namely “Lima Convention”),and the 1986Convention for the Protection of Natural Resources and Environment of the South Pacific Region and related Protocols(namely “Nouméa Convention”) 1986.16This was adopted in 1986 and entered into force in 1990.Parties to the Nouméa Convention are:American Samoa,Northern Mariana Islands,Australia,Cook Islands,Palau,Federated States of Micronesia,Papua New Guinea,Fiji,Pitcairn Islands,French Polynesia,Guam,Tokelau,Kiribati,Tonga,Marshall Islands,Tuvalu,Nauru,Vanuatu,New Caledonia,Wallis and Futuna,New Zealand,Western Samoa and Niue.The SPREP is the Secretariat for the Convention and convenes the biennial conference of the parties.The Convention is supported by two additional 1986 protocols:The Prevention of Pollution of the South Pacific Region by Dumping,and Concerning Cooperation in Combating Pollution Emergencies in the South Pacific Region.However,while parties to theNouméa Conventionhave focussed on the “protection,management and development of the marine and coastal environment”,17Virginia Wiseman,Contracting Parties to Noumea Convention Convene for Thirteenth Meeting,IISD website (21 Sept 2015),http://sdg.iisd.org/news/contracting-parties-tonoumea-convention-convene-for-thirteenth-meeting/.there appears to have been little attention given to wrecks or pollution arising from collisions at sea -although pollution from ships is specifically covered by the convention.A major obstacle is resource constraints which present significant challenges to pursuing targeted initiatives.18Aruna Lolani,Convention Exists to Protect Pacific,Samoa Observer (15 Sept 2017),http://www.samoaobserver.ws/en/15_09_2017/local/24345/Convention-exists-to-protect-Pacific.htm.Two additional protocols that could be relevant were agreed in 2006:TheProtocol on Oil Pollution Preparedness,Response and Cooperation in the Pacific Region,and theProtocol on Hazardous and Noxious Substances Pollution,Preparedness,Response and Cooperation in the Pacific Region.Neither has yet been brought into force.The SPREP has also produced various model laws,including aPacific Model Marine Pollution Prevention Actdrafted in 2000.19See Peter Heathcote,Marine Pollution Prevention Legislation in the Pacific Region -The Next Five Years,Maritime Studies,Vol.129,p.1-6 (2003).This does not,however,seem to have been adopted.As with other international laws,even if regional models are adopted,their implementation and enforcement requires resources which are simply beyond the capacity of most PICs.

Similarly,while an alternative approach might be to use existing environmental impact assessment mechanisms which are found in a range of statutes,20For example,the 2003 Environmental Impact Assessment Act (Tonga);the 2008 Environment Protection Act (Tuvalu);the 2000 Environment Act (Papua New Guinea) and the 2003 Environmental Management and Conservation Act (Vanuatu).for these to be effective,especially in assessing issues of compensation,there needs to be a “before” and “after” assessment.This type of data,especially when it comes to marine flora and fauna,may be missing or partial especially in countries where the resources and expertise to carry out such studies are limited.It is also recognised that any impact assessment has to be timely,in terms of establishing an initial framework for assessment,who is to carry it out and where,and over what period of time.There also needs to be a degree of flexibility in any framework because of differences in type of pollution,extent,geographical area,and social-economic impact.21See Ivan Calvez &Loïc Kerambrun,Post-spill Environmental Impact Assessment:Approaches and Needs,Uvigo (13 Nov 2018),https://tv.uvigo.es/video/5b5b45638f42085e 2c6f658b?track_id=5b5b45658f42085e2c6f6596.This requires human,technical and financial resources.

Clearly,in small States the resources and expertise may be limited and marine pollution events may take place in a relative vacuum of scientific evidence.Much of the national legislation imposes criminal sanctions for a range of noncompliance offences but any civil claims may have to be pursued separately.It then becomes incumbent on the courts to attribute liability and arrive at damages.With no specialist environmental courts,pursuing environmental damage claims is costly and complex.

C.Trans-shipment of Hazardous Pollution

Separately to the pollution of the ocean from wrecks and/or oil and other spills,pollution of the marine environment through the transhipment and dumping of nuclear and other hazardous waste has long been a concern to PICs,with the matter raised repeatedly at the Pacific Islands Forum. Early concern was raised by nuclear testing in the Pacific -the United State (1946-1958),the United Kingdom(1952-1957),and France (1966-1996).Pacific concern about nuclear dumping culminated in the 1985South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone Treaty(namely “Rarotonga Treaty”).22The South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone Treaty entered into force in 1986.Parties are Australia,Cook Islands,Fiji,Kiribati,Nauru,New Zealand,Niue,Papua New Guinea,Solomon Islands,Tonga,Tuvalu,Vanuatu and Samoa.All of these countries are within the South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone.Marshall Islands,Federated States of Micronesia and Palau lie outside this zone and are not parties.If they become parties,the Treaty will be geographical expanded to encompass them.The United Kingdom is a dialogue partner to the Treaty.The Treaty is supported by three Protocols.The continuing threat of pollution caused by the transhipment of nuclear waste remains a fear (although the actual risk is minimal) aggravated in 2021 by rumours that Japan was proposing to release contaminated water from the Fukushimo plant into the Pacific Ocean.There is also concern that nuclear waste stored in a land coffin on Runit Island in Marshall Islands could leak into the ocean as the storage unit ages,aggravated by rising seas and tropical weather patterns.Recent multilateral agreements between Australia,the United States and the United Kingdom,on the exchange of technology regarding nuclear powered vessels (not nuclear weapons) have reinvigorated concerns in this regard,possibly aggravated by misinformation and alarmism.While there is a regional instrument that can be called on the international dimension of this issue required compliance beyond the signatory parties.

III.Rising Seas

An area in which international law has been found to be wanting is that of rising sea levels.While coastal erosion and changes in the coastal areas of islands is not unusual (or the converse,the emergence of new islands as a result of volcanic activity,accretion and new coral masses) climate change has had a clearly noticeable effect on warming the temperature of the ocean and aggravating sealevel rise as well as triggering extreme weather conditions.For Pacific islands,used as they are to natural hazards such as cyclones,earthquakes,tsunamis and tropical storms,climate change is aggravating the risks of living on low lying atolls and islands.Coastal villages are losing land,freshwater lenses are being polluted by salt-water,while soil is increasingly salinized,leading to poor fertility and threatening food security.Pacific islands,therefore,face specific threats from climate change.

A.Forced Relocation due to Rising Seas

People are being displaced from their villages and having to relocate either on to higher ground if there is any or to other islands.In countries where almost all land is held under customary forms of land tenure,this is no easy task.The State does not own enough land to resettle all its climate refugees.If they move onto land owned by other customary owners,their tenure is insecure and any rights they acquire are secondary to the original owners’ rights. In some cases,Pacific island governments have sought to acquire land elsewhere,for example Kiribati has acquired land in Fiji,but such measures offer short-term relief only,because as populations grow there will be further pressure on land and incomers may not be welcome or conflicts may arise between the indigenous owners of the land and those that have resettled there.Elsewhere rather than resettle or abandon their island homes,governments have sought to erect barriers against the sea,for example sea-walls,as in Tuvalu.Clearly this requires financial support from the donor community and it is questionable as to how long such measure will succeed in keeping out the ocean.

There is also the question of identity and legal status.If Pacific islanders from one country are forced to seek sanctuary elsewhere because of rising seas,then they will lose their identity,becoming a minority in another’s land.In recent years,there has been a growing body of work on whether environmental refugees can or should be able to claim refugee status.23See Laura Westra,Environmental Justice and the Rights of Ecological Refugees,Human Rights Law Review,Vol.11:1,p.195-210 (2011);Benoit Mayer,The Concept of Climate Migration:Advocacy and its Prospects,Edward Elgar Publishing,2016;Jane McAdam,Climate Change,Forced Migration,and International Law,Oxford University Press,2012.Most recently this has been supported by a ruling by the United Nations Human Rights Committee acknowledged a legal basis for refugee protection for those whose lives are imminently threatened by climate change.24Yvonne Su,UN Ruling on Climate Refugees could be Gamechanger for Climate Action,Climate Home News (29 Jan 2020),https://www.climatechangenews.com/2020/01/29/unruling-climate-refugees-gamechanger-climate-action/,commenting on the ruling in CCPR/C/D/2728/2016,commenting on the ruling in CCPR/C/D/2728/2016.The claim is premised on the compulsion to leave a homeland because of environmental threat.However,the key legal criteria for refugee status remains fear of persecution in the country of origin on one of the five conventional grounds(race,religion,nationality,membership of a particular group or political opinion).To date litigation to claim the status of “climate change refugee” has not been successful,25See Ione Teitiota v. The Chief Executive of Ministry of Business,Innovation and Employment,[2013] NZHC 3125,[2014] NZCA 173,[2015] NZSC 107;Kelly Buchanan,New Zealand:“Climate Change Refugee” Case Overview,The Law Library of Congress,Global Legal Research Center,2015,which also includes reference to a number of other unsuccessful claims.Teitota’s case was considered by the UN Human Rights Committee -see note 24 -which ruled against him on the grounds that his like was not at imminent risk.although the Supreme Court in New Zealand did suggest (obiter) that there might in future be the possibility “that environmental degradation resulting from climate change or other natural disasters could … create a pathway into theUnited Nations Convention on Refugeesor protected person jurisdictions”.26Ione Teitiota v.The Chief Executive of the Ministry of Business,Innovation and Employment,[2015] NZSC 107,para 13;The current New Zealand government is also looking at a special class of refugee visa:Pearlman,The Straits Times,9 December 2017Even if this were to be the case,there is currently no agreed definition of the term “environmental or ecological refugees”. Essam El-Hinnawi,a UN Environment Programme expert,defined environmental refugees in 1985 as:“People who have been forced to leave their traditional habitat,temporarily or permanently,because of marked environmental disruption (natural and/or triggered by people) that jeopardized their existence and/or seriously affected the quality of their life”.27Essam E.Hinnawi,Environmental Refugees,UNEP website,https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/121267.The International Organisation for Migration issued a working definition in 2008:“Environmental migrants are persons or groups of persons who,predominantly for reasons of sudden or progressive change in the environment that adversely affects their lives or living conditions,are obliged to leave their habitual homes,or choose to do so,either temporarily or permanently and who move either within their country or abroad”.28International Organization for Migration,IOM Migration Research Series No.31:Migration and Climate Change,IOM website (15 Feb 2008),https://www.iom.int/news/iom-migration-research-series-no-31-migration-and-climate-change;Bonnie Docherty &Tyler Giannini,Confronting A Rising Tide:A Proposal for A Convention on Climate Change Refugees,Harvard Environmental Law Review,Vol.33:2,p.349-403 (2009).Arriving at an internationally agreed definition is difficult not only because of the many ways in which environmental change can impact on people’s livelihoods but also because creating a new class of migrants could exacerbate the challenges already faced by other classes of migrants and the countries to which they migrate.29In 2017 it was estimated there were 258 international million migrants.See European Parliament Research Service,The Concept of “Climate Refugee”:Towards A Possible Definition,EuroParl (Feb 2019),https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2018/621893/EPRS_BRI(2018)621893_EN.pdf.

Whatever descriptors are used,there are concerns about negative connotations which run counter to the plea by ex-President Anote Tong of Kiribati that what is required is migration with dignity before people are forced off their land due to sea-level rise.30Anote Tong,Migration is the “Brutal Reality” of Climate Change,Climate Home News(21 Jun 2016),https://www.climatechangenews.com/2016/06/21/anote-tong-migration-isthe-brutal-reality-of-climate-change/.Besides the fact that the label “refugee” is legally inaccurate,it is also resisted by Pacific islanders themselves,who reject the negative connotations associated with these terms.31Jane McAdam &Maryanne Loughry,We aren’t Refugees,Inside Story (30 Jun 2019),http://insidestory.org.au/we-arent-refugees/.More recent focus on resilience and adaptation in climate change discourse also shifts the narrative away from the idea of leaving these islands.This has raised a further legal question:Notably whether a State can continue to exists as a sovereign State if it has no land? To date international law has not addressed the question of sovereignty where a State’s lands are under water.32Daniela Maartines,Does the “Defined Territory” Include Submerged Land?,Cambridge International Law Journal (10 May 2021),http://cilj.co.uk/2021/05/10/does-the-definedterritory-include-submerged-land-some-notes-on-the-notion-of-territory-regarding-thelegal-concerns-presented-by-sea-level-rise/.It is a question Tuvalu would like an answer to.33Willian Booth &Karla Adam,Sinking Tuvalu Prompts the Question:Are You Still A Country if You’re Underwater?,The Washington Post,9 November 2021.

International law is also unclear as to whether PICs at risk of shrinking land masses -bearing in mind that these are small to begin with,can continue to claim their original territorial seas and EEZs.This is because these are usually measured from identified points on the land.As the wealth of most Pacific islands lies in the seas that surround them,any shrinking of their territorial seas or EEZs clearly has the potential to have a significant economic impact.Indeed,such is the concern of PICs that in August 2021 Pacific island leaders agreed aDeclaration on Preserving Maritime Zones in the Face of Climate Change-Related Sea-Level Rise.The Declaration affirms that “once Pacific islands have established and notified maritime zones to the secretary-general of the United Nations,they will be fixed irrespective of changes to the shape and size of islands.”34Lagipoiva Cherelle Jackson,Pacific Forum Leaders Set Permanent Maritime Borders,as Rising Seas Shrink Islands,The Guardian (12 Aug 2021),https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/aug/12.Whether the international community agrees remains to be seen as currently maritime zones are fixed from land-based points,although the Pacific islands have been long-time advocates of using global positioning system coordinates to determine maritime zones rather than land-based features.

IV.Illegal,Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) Fishing

As has been indicated most Pacific islanders are coastal dwellers.Consequently,they rely on the sea to provide the bulk of their protein,to provide natural resources to sell at local markets and to meet social and cultural communal obligations.The tourist trade,which is an essential component of many Pacific island economies,also relies on small-scale commercial fishing to meet tourism demand.For many PICs revenue generated through commercial fishing,either directly or more often through the licensing of foreign ships,is a significant source of national income.In Kiribati for example,fishing licence revenue accounted for 85% of total revenue growth between 2011 and 2018 (75% of all government revenue in 2016).35James Webb,Kiribati Economic Survey:Oceans of Opportunity,Asia and the Pacific Policy Studies,Vol.7,p.5-26 (2020).Similarly,in Solomon Islands fisheries is a significant revenue stream with tuna resources earning 51 million USD in 2017.36Ronald Toito’una,Solomons Makes $399M from Tuna Alone,in 2017,TunaPacific (2 Mar 2018),https://www.tunapacific.org/2018/03/02/solomons-makes-399m-from-tuna-alonein-2017/.This is primarily from licencing fees from foreign owned vessels.Unlike Kiribati however,there is some fish processing in Solomon Islands.

Illegal fishing and weaknesses within enforcement and regulatory agencies are a problem throughout the Pacific.37Widjaja,et al.,Weak Governance and Barriers to Enforcement Are Key Drivers of IUU,OceanPanel,https://oceanpanel.org/sites/default/files/2020-02/HLP%20Blue%20Paper%20 on%20IUU%20Fishing%20and%20Associated%20Drivers.pdf.The Pacific Islands Forum Fisheries Agency has identified four areas of concern:(i) IUU fishing;(ii) misreporting of catches;(iii) non-compliance with licensing conditions;(iv) post-harvest risks such as transshipment of catches.Using data from 2010-2015,it estimated in 2016 that IUU activity in Pacific tuna fisheries amounted to 306,440 tonnes,with an ex-vessel value of 616.11 million USD (the average regulated annual tuna catch 2014-2018 was 2.7 million tonnes).The bulk of IUU activity was purse seine fishing (70%)composed of skipjack tuna (33%),yellowfin tuna (31%),and bigeye (19%).38Forum Fisheries Agency Quantifying IUU Report 2016,FFA website,https://www.ffa.int/files/FFA%20Quantifying%20IUU%Report%20-%20Final.pdfMost IUU fishing is done by licenced vessels either fishing in areas for which they are not licenced or outside of their licenced limits/catch quotas.

PICs make concerted efforts to regulated fishing to ensure sustainability and to try and prevent illegal fishing.There are several regional fisheries management organisations.These include:

•The Pacific Islands Forum Fisheries Agency (FFA) which promotes regional co-operation and support to develop fisheries policies to build capacity and regional solidarity for the sustainable management of tuna in the Pacific.FFA nations control the Western and Central Pacific Fishery Commission (WCPFC),39Members are:Australia,Cook Islands,Federated States of Micronesia,Fiji,Kiribati,Marshall Islands,Nauru,New Zealand,Niue,Palau,PNG,Samoa,Solomon Islands,Tokelau,Tonga,Tuvalu and Vanuatuwhich accounts for around 52% of the world’s catch of tuna and 49.8% of the total value.40Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resource Development and Ministry of Finance and Economic Development of Republic of Kiribati, Fishing Licences Revenues in Kiribati 2017 Report,MFEDKI,https://www.mfed.gov.ki/sites/default/files/Fishing%20License%20 Revenues%20in%20Kiribati%20Report%202017.pdfTuna is worth 2.6 million USD to FFA countries.

•The Secretariat of the Pacific Community (SPC) which is the regional centre for tuna fisheries research,monitoring,stock assessment and data management

•The Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC) which is responsible for the management and conservation of tuna in the Western Central Pacific Ocean and was established by theConvention on the Conservation and Management of Highly Migratory Fish Stocks in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean

•The Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission (IATTC) which is responsible for the conservation and management of tuna and other marine resources in the Eastern Pacific Ocean

•The South Pacific Regional Fisheries Management Organisation(SPRFMO) which was established by theConvention on the Conservation and Management of the High Seas Fisheries Resources in the South Pacific Oceanto manage non-migratory species through an eco-system and precautionary approach to fisheries management.

These agencies and their work are indicative of the significance of the Pacific Ocean to Pacific economies and the extent of the existing engagement in efforts to manage its resources effectively and sustainably.A sub-organisation is the PNA (Parties to theNauru Agreement Concerning Cooperation in the Management of Fisheries of Common Interest) which established the Vessel Day Scheme (VDS,which replaces thePalau Agreement).This agreement limits fishing efforts in the combined EEZs of the eight member States (Federated States of Micronesia,Kiribati,Marshall Islands,Nauru,Palau,Papua New Guinea,Solomon Islands and Tuvalu).Parties to theNauru Agreementprovide about 50% of the global supply of skipjack tuna.The VDS applies to purse seine fishing vessels and is a fisheries management tool independent of prices and volume,based on a charge per day for fishing effort.The aim -which has been largely successful,is to prevent over-fishing.41World Economic Forum,These Pacific Islands Have An Innovative Scheme to Prevent over Fishing in Their Waters,weforum website (26 Jun 2021),https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/06/subsidized-fishing-man-made-tragedy/.These frameworks,however,are undermined by IUU fishing which is difficult to patrol and even more difficult to successfully prosecute due to the movement of ships and their catches,the size of EEZs and the scarcity of patrol vessels in this vast expanse of ocean.

V.Deep Sea Mining

While climate change poses a number of risks to Pacific islands,so do the solutions proffered to tackle it.In particular,the advocacy of electric vehicles in developed countries to replace those driven by fossil fuels,places a premium on the metals needed to make batteries for these vehicles.Similarly,the storage solutions for energy harvested from renewable sources (such as wind and solar) demand rare metals.With developed countries vying for pre-eminence in achieving carbon reduction targets,it is inevitable that demand for such metals will outstrip current supplies.Indeed,it is estimated that the green transition touted by climate change advocates will require hundreds of millions of tonnes of these metals.New sources will need to be found.One of the identified potential sources is the deep seabed,including the deep seabed off the coasts of PICs,either within the EEZ of States,or the area under international waters belonging to the global commons -the common heritage of humankind.

While exploratory mining has suggested that such metals can be found in nodules lying on the seabed,seamounts rising from it,and near vents of superheated water occurring along volcanic ridges,the very nature of the deepsea bed means that little is known about its bio-diversity or the micro-organisms within it which may be essential to human futures.Scientific exploration and analysis is only just beginning.Some estimates are that only 0.01% of the total area of Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) alone has been sampled by scientists and that 85% of the global seabed remains unmapped.42Wil S.Hylton,20,000 Feet under the Sea,The Atlantic (Jan/Feb 2020),https://www.exploreiowageology.org/assets/text/MayCapstone/MiningOurOceans_AtlanticJan2020.pdf.What is clear is that vertical and horizontal eco-systems are mutually interdependent and that threats to any threaten all.

Of particular interest in the Pacific,is the CCZ,and area of seabed 4000 metres below the ocean surface and over 4.5 million square kilometers in size.The CCZ holds polymetallic nodules holding nickel,copper,manganese and other precious ores.One estimate is that the CCZ mineral wealth far outstrips land-based sources of copper,nickel,and cobalt.While 1.44 million square kilometers have been set aside as areas of Particular Environmental Interest Zone (APEI),protected from resource extraction,current exploration contracts cover 1.2 million square kilometers.To date,PICs,Nauru,Kiribati,Cook Islands and Tonga have engaged with explorations initiatives in the CCZ and their own neighbouring EEZs linking withThe Metals Company(Canada).Tuvalu has applied to be considered during 2022.

As is evident (see Figure 1) there is international competition in the area with exploration activities being carried out by China,Russian Federation,France,Germany,Belgium,Japan,Norway,Singapore,the Republic of Korea,United Kingdom,Cuba,Bulgaria,Poland and the Czech Republic and a conglomerate of the Russian Federation.It is also evident from the map that despite the demarcation of APEI on the margins of the CCZ,and the protected areas within it,there is nothing to prevent the consequences of exploration activities,and ultimately mining,spreading to these areas because there are no solid boundaries.

Figure 1 Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone Exploration Areas for Polymetallic Nodules43Data source:ISA website,https://www.isa.org.jm/,2018.

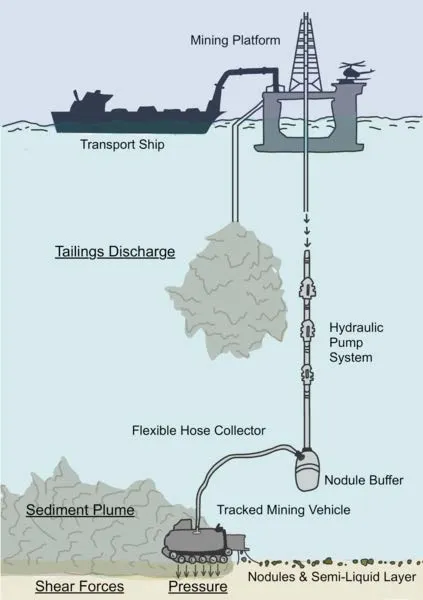

Figure 2 Deep-sea Mining Process48Figure source:https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mining_implications_figure.png.

A.Environmental concerns

About 90% of the species discovered in the deep seabed is new to science.This is significant not only because eco-systems are interdependent but also because mining contractors are required to assess what lives in their claim area in order to understand how mining equipment will impact on these systems.Baseline data however may be inaccurate or insufficiently robust.Scientists assert that the large-scale implications for deep-sea species can only be properly assessed with better knowledge of how the relevant ecosystems function.44Sabine Christiansen,Harald Ginzky,Katherine Houghton &Annemiek Vink, Environmental Governance of Deep Seabed Mining -Scientific Insights and Food for Thought,Marine Policy,Vol.114,103827 (2020).

While Pacific Islands such as Cook Islands recognise the need for baseline studies,mitigation strategies and monitoring,they may lack the resources to carry these out themselves.They are therefore dependent on the mining companies to provide these,and there are question marks around the transparency,objectivity and rigor of these and also problems in sharing data to acquire a better understanding of the marine species.

Exploration studies tend to use small scale remotely-controlled machines not the large robotic machines,about the size of combine harvesters,which will be used if,following exploration licences,full mining licences are granted.These large machines will suck up the top 10 centimetres of the ocean floor,disturbing sediment which could disperse across a large area of the sea,and remove all nodules (including young ones),effectively destroying the seabed and the habitat it provides.Mined nodules and sediment will be pumped up a long tube to a surface support-vessel where nodules will be sorted and waste (undersize nodules,sediment etc.) returned to the sea either at surface level or down a tube to deeper water.

A study by the Royal Swedish Academy of Science predicted that each mining ship would release about 2 million cubic feet of discharge every day,some of it containing toxic substances such as lead and mercury.45Ibid.Greenpeace has estimated that sediment could travel “hundreds or even thousands of kilometres”.46Greenpeace,Protect the Oceans,GoogleApis (Jun 2019),https://storage.googleapis.com/planet4-international-stateless/2019/06/f223a588-in-deep-water-greenpeace-deep-seamining-2019.pdf.There is also the issue of noise created by mining vehicles and activities negatively impacting on cetaceans (whales).In the Pacific this is a concern not only because in 2017 eleven PICs signed up to thePacific Islands Year of the Whale Declarationto strengthen whale conservation across the region,47These are Australia,New Zealand,Cook Islands,Fiji,New Caledonia,Palau,Papua New Guinea,Samoa,Tokelau,Tonga and Tuvalu.For the full text see 11 SPREP Members Sign On To Pacific Whale Declaration,SPREP website (6 Apr 2017),https://www.sprep.org/news/11-sprep-members-sign-pacific-whale-declaration.The United Kingdom supported the Pacific Islands Year of the Whale Declaration on behalf of Pitcairn at a side event to CMS COP12.France also supported this.but also because for States like Tonga,whale watching is a vital contributor to tourism.

The riches offered by deep-sea mining,or at least by companies engaged in deep-sea mining,are tempting to PICs,especially at the present time,when many have seen tourism revenue decimated due to the COVID-19 pandemic and border closures.Many PICs,however,and even sectors within those countries which support deep-sea mining -such as Cook Islands and Tonga,have called for a moratorium of such mining until the scientific knowledge is much greater.These calls have been supported by a range of regional,local and international organisations.49Luke Hunt, NGOs and Scientists Urge Moratorium on Deep Sea Mining in the Pacific-Mining for Battery Metals Seen as A Threat to Pacific Island Nations,The Diplomat (20 May 2020),https://thediplomat.com/2020/05/ngos-and-scientists-urge-moratorium-on-deepsea-mining-in-the-pacific/.The Pacific Network on Globalisation,for example,has urged caution,stressing the importance of the need for full and informed prior consent from Pacific communities,the adoption of the precautionary principle when considering possible environmental impact,and the importance of potential trans-boundary impacts.It has also warned of accepting legislation and policies influenced by bodies outside the region which may not sufficiently consider indigenous rights.TheDeep Sea Mining CampaignandMiningWatch Canadahave highlighted that this is not simply a national issue for individual States to decide,stating that “the interconnected nature of the ocean means that impacts would be felt region wide”.50Ibid.Similarly,the view has been expressed that “given the Pacific community’s relationship with the ocean,regional governments had no social licence to pursue deep sea mining”.51Johnny Blades,Warning for Pacific Governments Gambling on Deepsea Mining,RNZ website (14 Aug 2020),https://www.rnz.co.nz/international/pacific-news/423537/warningfor-pacific-governments-gambling-on-deepsea-mining.

B.Legal Frameworks

Unfortunately,the current international legal framework to govern the deep seabed is inadequate.Authority vests in the International Seabed Authority (ISA),an autonomous United Nations body which was established in 1994 under the 1982United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea(UNCLOS).It has 68 members,which meet once a year in Jamaica.The ISA has the task of promoting and regulating sea-bed mining outside EEZs.It is this Authority that has responsibility for issuing exploration licences.Applicants must either be State signatories to UNCLOS or sponsored by such a State.That State has responsibility to ensure

that a contractor observes UNCLOS and ISA rules.The International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea has published an advisory opinion on the responsibilities and obligations of States in this regard,which sets high standards of due diligence.52Responsibilities and Obligations of States Sponsoring Persons and Entities with Respect to Activities in the Area (Request for Advisory Opinion submitted to the Seabed Disputes Chamber),Case No 17,1 February 2011,Seabed Disputes Chamber of the International Tribunal of the Law of the Sea.To date,the ISA has granted thirty-one 15-year exploration contracts for deep-sea areas in the Atlantic,Pacific and Indian Ocean.Of these at least 17 are for about 20% of the CCZ,and five are for cobalt-rich crusts in the Western Pacific Ocean.

The ISA’s mandate is not however to prevent deep-sea mining.Rather it must protect the international seabed from serious harm.To this end it makes recommendations to contractors in respect of possible environmental impacts arising from exploration.It currently does not have in place any detailed standards or rules for the conduct of environmental impact assessments.Similarly,although work has been in progress since 2014,ISA is still drafting exploitation regulations for potentially high-impact,full-scale mining.These regulations are intended to address environmental impact assessment,monitoring and habitat protection.To date the draft has not been approved by members.Although ISA planned to complete these regulations in 2021 this has not been achieved.

Greenpeace claim that ISA is increasingly subject to lobbying by mining companies some of whom speak on behalf of government delegations at the ISA meetings.These companies also prepare and fund government applications for exploration contracts.This is particularly likely to happen in countries where there is a lack of autonomous technical skill.Similarly,the High-Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy has expressed concerns about the governance of ISA,the lack of transparency and apparent mining-approval bias.

There is also concern that while exploration licences are meant to be limited to research,when carried out by mining companies this research may be far more focussed on the mineral wealth of the sea-bed than on the marine species and bio-organisms that may be affected by that research.There are also concerns that the ISA lacks an environmental or scientific assessment group.Applications for contracts are considered by a legal and technical commission dominated (it is claimed) by lawyers and geologists.54Jonathan Watts,Deep-sea “Gold Rush”:Secretive Plans to Carve Up the Seabed Decried-Greenpeace Report Warns Against Granting Licences to “Deeply Destructive” Industry with Opaque Oversight,and Calls for Global Ocean Treaty,The Guardian (9 Dec 2020),https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/dec/09/secretive-gold-rush-for-deep-seamining-dominated-by-handful-of-firms.If members of ISA cannot agree a Code of Practice,there is the danger that explorations permits will expire before rigorous regulation is in place.Given the resources expended there may then well be pressure on ISA to grant mining permits.There is also a loophole,exploited most recently by Nauru.Once an exploration permits expires,ISA is compelled to grant an interim two-year exploratory contract,during which time it must put in place the necessary regulatory regime,which should -among other things -include environmental protections.

While ISA only has governance over the international seabed (the Area),UNCLOS (Part XII,Art.208) requires national jurisdictions to provide environmental protections for seabed mining within areas covered by their own EEZs that are “no less effective” than those of ISA.55James Sloan,Seabed Mining in the Pacific Ocean:To mine or not to mine? Exploring the legal rights and implications for Pacific Island Countries,Siwatibau and Sloan (4 Oct 2018),http://www.sas.com.fj/ocean-law-bulletins/seabed-mining-to-mine-or-not-tomine-a-trending-topic-for-the-pacific-island-countries-but-what-are-the-legal-rights-andimplications-for-goo-15385323.In 2016 the Secretariat of the Pacific Community,with support from the European Union,launched a project to support and inform the “careful governance of any deep-sea mining activities in accordance with international law,with particular attention to the protection of the marine environment and securing equitable financial arrangements for PICs and their people”.It released framework documents to provide guidance to PICs in setting up effective financial and environmental systems.56Allen L.Clark,A “Golden Era” for Mining in the Pacific Ocean? Perhaps Not Just Yet,EWC (6 Apr 2018),https://www.eastwestcenter.org/news-center/east-west-wire/“goldenera”-mining-in-the-pacific-ocean-perhaps-not-just-yet.

Having national legislation in place is therefore one of the obligations under UNCLOS and ISA,but it has to be accompanied by effective regulations and enforcement.There have been proposals to draft a regional Pacific seabed treaty,57Hannah Lily,A Regional Deep-sea Minerals Treaty for the Pacific Islands?,Marine Policy,Vol.70,p.220-226 (2016).but this does not seem to have advanced.

Unfortunately,there is significant power-asymmetry between large international mining companies and PICs,58Michael G.Petterson and Akuila Tawake,The Cook Islands (South Pacific) Experience in Governance of Seabed Manganese Nodule Mining,Ocean and Coastal Management,Vol.167,p.271-287 (2019).and even if such mining yielded economic rewards,the Pacific experience of the establishment and management of trusts such as Sovereign Wealth Funds,has not always been a positive one.Promises of tax revenues and royalties from deep-sea mining may repeat the types of issues that have affected promised income streams from logging and land mining.Promises of employment may similarly be ephemeral:The actual mining will be carried out by robotic machines,the selecting and separation processes take place at sea on foreign owned vessels and the resulting metal processing will occur elsewhere -raising separate but related environmental concerns.

Damage to the ocean will have long term consequences for Pacific islanders,affecting the marine resources they depend on,their coastal areas and the safety and security of the seas that surround their islands.Short term gains -largely for the developed world,may lead to long-term losses,the brunt of which will be borne by future generations of Pacific islanders.

VI.Conclusion

Pacific islanders see themselves as guardians of the Pacific Ocean.They also see themselves as large ocean States not small island States and working together through regional organizations they have developed a contemporary narrative of the “Blue Pacific” to headline policy and positioning in this geo-strategically significant ocean.

The “Blue Pacific” first emerged as a rallying call for PICs in September 2017 at the 48th Pacific Islands Forum meeting held in Apia,Samoa,providing a trope for Pacific collective identity and action.The aim behind the theme is to “strengthen the existing policy frameworks that harness the ocean as a driver of a transformative socio-cultural,political and economic development of the Pacific”.59Opening Address by Prime Minister Tuilaepa Sailele Mailelegaoi of Samoa to open the 48th Pacific Islands Forum 2017,Pacific Islands Forum (5 Sept 2017),https://www.forumsec.org/2017/09/05/opening-address-prime-minister-tuilaepa-sailele-mailelegaoi-samoa-open-48th-pacific-islands-forum-2017/.Emphasis is placed on the shared stewardship of the Pacific and the value of collective action.The theme of the “Blue Pacific” was further endorsed at the 49th Pacific Islands Forum,in Nauru in September 2018,as a means of prioritising collective action along the theme ofBuilding a Strong Pacific:Our People,Our Islands,Our Will.60Building A Strong Pacific:Our People,Our Islands,Our Will,Pacific Islands Forum (3 Sept 2017),https://www.forumsec.org/2018/07/31/building-a-strong-pacific-our-people-ourislands-our-will/.A number of priorities were articulated including environmental security and regional cooperation in “building resilience to disasters and climate change”.61Ibid.2050 Strategy for the Blue Pacific Continentby the Pacific Islands Forum is the articulation of steps that need to be taken to achieve the vision of a “Blue Pacific” through collective effort.It focusses on drivers of change (events,actions and decisions) which will have significant impact and therefore need to be addressed as a priority.The strategy was expected to be finalised in late 2021 but was delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic.Pacific leaders met in July 2022 to agree the framework and add detail to the strategy.

The “Blue Pacific” provides a focus for PICs to advance not only a shared agenda regarding the resources and security of the ocean that surrounds them but also a collective diplomatic platform for engaging in international discussions regarding environmental threats,climate change and the exercise of control over marine resources.62The Blue Pacific:Pacific Countries Demonstrate Innovation in Sustainably Developing,Managing,and Conserving Their Part of the Pacific Ocean,Pacific Islands Forum (7 Jun 2017),https://www.forumsec.org/2017/06/07/the-blue-pacific-pacific-countriesdemonstrate-innovation-in-sustainably-developing-managing-and-conserving-their-part-ofthe-pacific-ocean/.Introducing the “Blue Pacific” concept at the United Nations Oceans Conference in New York in 2017,the Samoan Prime Minister drew attention to how the Pacific Ocean has created an “inseparable link between our ocean,seas and Pacific Island peoples:their values,traditional practices and spiritual connections”.63Remarks by Hon.Tuilaepa Lupesoliai Sailele Malielegaoi Prime Minister of the Independent State of Samoa at the High-Level Pacific Regional Side event by PIFS on Our Values and identity as stewards of the world’s largest oceanic continent,The Blue Pacific,Pacific Islands Forum (5 Jun 2017),https://www.forumsec.org/2017/06/05/remarks-byhon-tuilaepa-lupesoliai-sailele-malielegaoi-prime-minister-of-the-independent-state-ofsamoa-at-the-high-level-pacific-regional-side-event-by-pifs-on-our-values-and-identity-asstewards/#:~:text=Pacific%20leaders%20urge%20the%20world%20to%20recognize%20 the,key%20to%20a%20sustainable%20future%20for%20our%20ocean..While Dame Meg Taylor,former Secretary General of the Pacific Islands Forum,has stated that:

...[T]he Blue Pacific narrative helps us to understand,in and on our own terms,based on our unique customary values and principles,the strategicvalue of our region.It guides our political conversations towards ensuring we have a strong and collective voice,a regional position and action,on issues vital to our development as a region ...64Blue Economy about Pacific determining own agenda:Dame Meg,Pasifika Arising (4 Oct 2018),https://www.pasifikarising.org/blue-economy-pacific-determining-own-agendadame-meg/.

To date the2050 Strategy for the Blue Pacific Continenthas focused on the development of a shared vision,the identification of factors impacting the future of the region -a number of which are indicated in this paper,priorities for national and sub-regional bodies and selection of major focus themes.What has not yet been considered is how strategies will be developed to achieve the ambitions of each thematic area.It is at this stage that some consideration will need to be given to the role of law in providing the frameworks for the achievement of goals if policy and ambitions are to be translated into real effect.Where there is consensus on the goals then it is likely that legal frameworks will need at the very least to be regional and to tie in with the international legal order.As the above discussion has indicated there are some successful regional legal frameworks but there are also many missed opportunities where work has been done on model laws to address a perceived need,but these have not been adopted or implemented.Moreover,given some of the weaknesses of international law in specific areas of environmental threat and ecological risk in the region,highlighted in this paper,there will certainly be challenges,especially in ensuring that within the “Blue Pacific” no one is left behind.