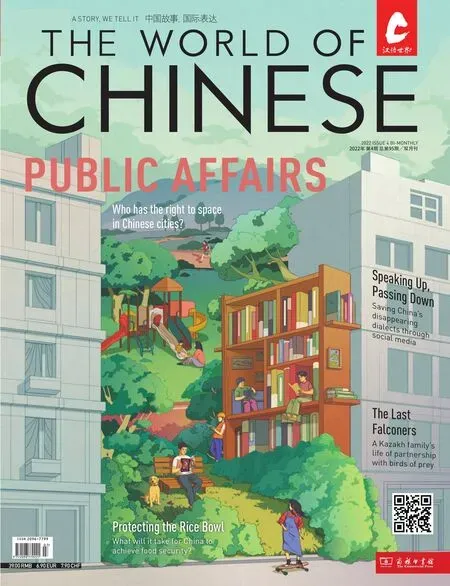

PUBLIC AFFAIRS

ILLUSTRATION AND DESIGN BY CAI TAO AND FENGZHENG YISHENG,PHOTOGRAPHS FROM VCG

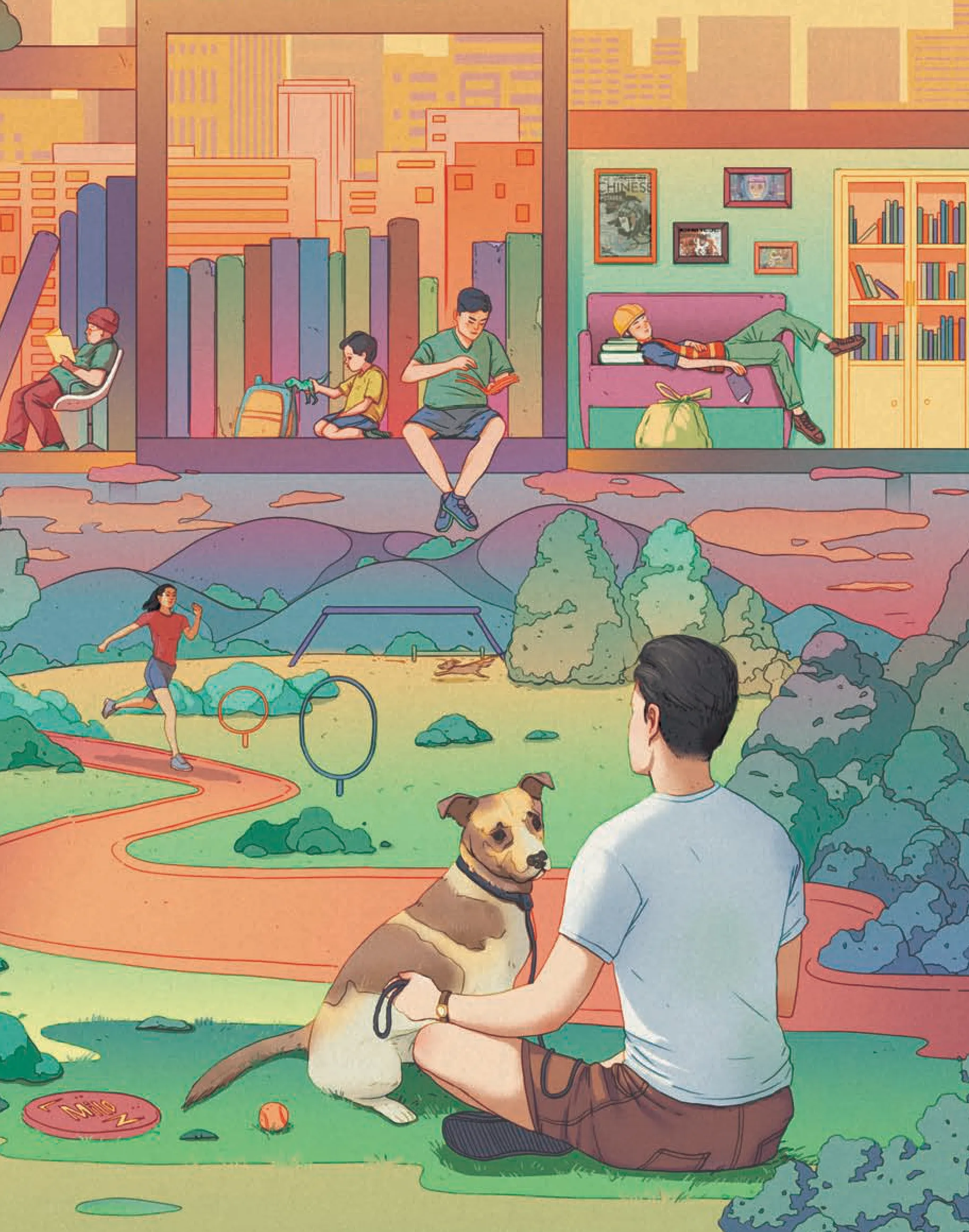

Despite having some of the largest public squares in the world,urban China suffers from a conspicuous lack of spaces for people to gather,relax,and interact.China’s city planners are belatedly awakening to the need for more parks,riversides,and shared spaces to improve residents’ health and quality of life.Meanwhile,local governments are investing in libraries to provide comfortable areas for anyone to spend their time in safety,and are turning some of them into one-stop community service centers.Yet in both these cases,what appears open to all may be “confined,” while the pandemic has created barriers to creating more open spaces.

Pets,too,struggle to find welcoming spots to hang out,with urban authorities increasingly restricting where owners can take their animal friends,and regulating pet behavior with fines and even bans.China’s urban residents,animals and humans alike,continue to navigate ways to enjoy public space together.

疫情让人们更深地认识了公共空间的可贵。

人们走向街头、公园、图书馆等公共场所,

寻求物理或精神的“庇护”。

然而,诸多因素将一些人和宠物拦在了门外。

公园的设计师、图书馆的管理者也在探索如何

更好地服务大众,尤其是弱势群体。

真正免费开放的公共空间离我们还有多远?

PARKS,NO RECREATION

China is trying to build more public spaces,but who has the right to use them—and how—remains contested

Lin Qiuming couldn’t tell if she was out for a stroll,or starring in a spy movie.Throughout May,the young journalist had gotten used to dodging roving guards and blockedoff paths whenever she came to the Liangma River—one of the only outdoor hangouts still available in Beijing during a Covid outbreak that month—in search of the bench or tree where she’d agreed to meet a friend or an interviewee.“It was like we were using code;it felt very surreal,” she tells TWOC.

Nicknamed the “Seine of Beijing”by residents of the capital,the 9.3-kilometer river,which runs through the affluent Chaoyang district,saw unprecedented traffic after the city shut down indoor dining and most other public venues,including outdoor parks,to contain the spread of the virus on May 1,which was also the start of a threeday public holiday.In the subsequent weeks,the riverbanks became a makeshift restaurant,cafe,gym,sports field,and even a public dance floor,hosting all the social activities that middle-class urbanites no longer had a space for.

But the good times didn’t last.Barely a week later,security guards put tape and iron sheets around some of the grassy areas.By the end of the second week,there were checkpoints by parts of the river where one had to scan a QR “health code” to enter,and gatherings of people were frequently broken up by patrolling security guards.Lin and her friends brought a picnic to the river one day and“played hide-and-seek” with guards for several hours before they finally gave up,she says.

“The fundamental function of the public space is to provide space for the public to have interactive activities,” says Lai Wenbo,the head designer of Guangzhou’s LAI studio,which has designed over 20 such spaces,including parks and campsites,across China.In Beijing,such places are rare.The Liangma River was one of the few that “had no requirements,no time limits,” where one could “sit on the ground to experience closeness with nature,” as Chinese magazine Portrait put it.

The Liangma River has been a popular hangout spot for Beijing residents,especially during the Covid-19 pandemic

Covid-19 has heightened the precarious existence of such spaces around the country.Spaces like the Liangma River,or Shanghai’s West Bund and Xi’an’s Qujiang Lake,were non-commercial,had no opening hours,and were relatively hard to close off or patrol due to their length.At various points during this year,they were the only substitutes in their respective cities for KTVs that closed during the pandemic,the restaurants and cafes that had suspended dinein services,the malls that required negative nucleic acid test results to enter,and the parks that were either closed completely or limited access.

“It would give me this feeling that you need to be healthy,or normal to be qualified to enter the parks that you used to be able to enter randomly,” says Lin of these restrictions.Even the remaining open spaces,like the Liangma River,gave her a sense of panic:“You feel like they could be closed anytime…we need to take the opportunity and use it as soon as possible,or it will close again.”

Shen Maohua,a prolific columnist and critic who often writes about urban spaces under the pen name Wei Zhou,believes China does not yet have true public spaces—rather,it has “confined spaces.” “It’s the idea that the existence of public spaces,the scale of their openness,the degree of their vitality,all need to be confined,” Shen explained to TWOC,mentioning that the gates,the tickets and the memberships that are required to enter supposedly public spaces,including even parks,are tools of control over who can use them,how,and how much.

Landscape design in China has traditionally focused on gated and enclosed spaces—as typified by the imperial gardens and courtyard homes of the ancient elite.Even gathering spaces in rural areas were not exempt:Village squares tended to be surrounded by homes of related families,and ancestral temples hosted gatherings only for people of a common lineage.

Many parks in cities have been barred to prevent gathering during the pandemic

With the founding of the PRC in 1949,the public space began functioning as the representation of socialist ideology.The government built outdoor spaces like public squares and monuments,which often served as places for the public to study socialism or criticize those suspected of not adhering to socialist beliefs.Recreational spaces,on the other hand,tended to be found within schools,factories,military compounds,and other “work units,”which organized group exercises and dancing,and offered communal facilities for those working within their sprawling campuses.

The demand for truly “public”spaces,not reserved for any special activity or specialized group of people,rose sharply after the reform period.During the period of relative openness of the 1980s,young people and workers,including students who finally returned to universities after the Cultural Revolution,gathered in public squares or college parks to discuss their concerns over the country’s future and demand reform.When China entered the 90s,under the impact of globalization,urban design adopted international standards with commercialized urban plazas and Western-style pedestrianized streets.

As the prevalence of public space has risen,so too have conflicts between different groups over who has the right to a public space,and how it ought to be used.Retirees who gather in public squares to exercise,often by dancing to loud music,in the early mornings and late evenings,have attracted noise complaints from their neighbors.Infamously,fed-up residents of one neighborhood in Changsha,Hunan province,pelted their local square dancers with feces on three separate occasions between 2012 and 2013.Police in the city of Luoyang in Henan province have broken up at least two brawls in recent years between retirees dancing on public basketball courts,and young men trying to play a pick-up game.

In the last decade,China has begun emphasizing public space in urban planning.“Urban construction changed from the previous big move on demolition and reconstruction to upgrading and optimizing present urban public spaces,” says Lai.In 2015,President Xi Jinping advised the government to focus on the “livability”of cities,rather than just GDP,and“assure balance between spaces of production,living spaces,and ecological spaces.” In 2021,the State Council announced that there were about 18,000 city parks in China,an increase of 50 percent compared to 10 years ago.

Along with building more public spaces,some cities have stopped charging people for using them.Of the 406 parks in Shanghai,392 stopped charging entrance fees as of 2021,according to the city’s environmental sanitation bureau,and Beijing’s Chaoyang Park went free in February of the same year.Some parks,like People’s Park in Shanghai,have also removed walls and fences from their landscaping.

Yet just because such spaces are being built or opened up,doesn’t mean the public can always use them as they wish.Chinese officials continue to be sensitive to public gatherings,especially those that could turn political.“Stability” has been a leading principle in Chinese governance since Deng Xiaoping articulated it to the CPC Central Committee.Under this rule,public activities that might lead to disorder or even instability have been carefully controlled.

In 2020,when Premier Li Keqiang called on cities to develop the “street stall economy (地摊经济)” to boost the post-pandemic economy,the project was quickly shut down in Beijing amid complaints about hygiene and disorder,with Beijing Youth Daily claiming street stalls didn’t suit the capital city and it should “maintain the orderliness that a city should have.”

Shen believes the lack of physical public spaces in China also leads to the lack of a “public,” as defined by German philosopher Jurgen Habermas as a “realm of social life” where public opinions can be shared.Lin has observed that,since the pandemic started,she’s felt an increased desire to meet people in person rather than online,as she thinks online discussions are irrational,lack real continuation or connection,and can lead to extremism.“I feel the lack of public spaces could lead to this type of aggression becoming more severe,”she says.

“China is in the transitional period during modernization,which means the rules for public communication are still being established,” Shen says.He believes that ordinary people still have a deep-seated fear of chaos,leading them to value order rather than “vitality.”

This is especially true during the pandemic.“The Chinese public has the highest acceptance levels in the world when it comes to prevention policies such as lockdowns,which means,to them,public life is not as important as their safety,” says Shen.

He believes the situation will only change when Chinese society becomes more accepting of diversity.“The public,who feel discomfort and unease about the inclusiveness of public spaces,demand ‘confined spaces,’ and these confined spaces in turn have also shaped [the character of] the public.”

The iron sheets beside the Liangma River have now been removed.But with the pandemic still raging,they may not be gone forever.In some ways it took their closure for Lin and others to truly appreciate the value of such areas,even if the circumstances were far from ideal.“It’s awkward that we rediscovered public spaces this way,” says Lin.——ANITA HE (贺文文)

Retirees playing music or dancing to loud music is a common scene in public parks

READING SPACES

How did public libraries become safe havens for China’s vulnerable?

An hour’s subway ride separates 28-year-old Su Ying from her home in Beijing’s southwestern Fengtai district and what she calls her “hiding”place:the Chaoyang District Library.Her parents don’t know that she was laid off from her job at an education company last December and that she now spends nearly every day at public libraries working on job applications and studying for the national postgraduate exam.

At 10:30 a.m.,Su’s usual spot is occupied,forcing her to walk around the library for some time before finding a seat.Surrounding her today,as usual,are people from all walks of life:a middle-aged man in a black suit staring at stock prices on his computer screen;another reading a book about Buddhism and the news on his phone at the same time,a soda in hand.A woman in her 20s is taking notes while watching an online class,and getting annoyed at music filtering through the headphones of a nearby young woman who is watching a TV show on her phone.

For Su,and millions of other ordinary people in China,the country’s 3,212 public libraries (as of the end of 2020,according to statistics of the Ministry of Culture and Tourism) are ideal places for passing time with free wifi,as is now often the case.For the down-ontheir-luck or vulnerable,the library can be an escape from overcrowded living conditions,or even a shelter from domestic violence and natural disasters in a nation where such facilities are still in short supply.

But while growing in number and becoming more comprehensive in their services,China’s libraries have yet to meet all the needs of its population.There is just one library for every 438,000 people in China,and most libraries are concentrated in urbanized,economically developed areas (for comparison,the ratio in the US is 1 to 36,000 people).Pandemic restrictions,funding shortages,and concerns for public order have also prevented many libraries from serving as wide a community as they might wish.

Before she discovered libraries,Su’s go-to hangout was a Starbucks near her former office in Chaoyang district.She would buy a coffee and spend a whole day there applying for jobs,reading the news,and watching TV shows.This cost her at least 50 yuan per day,and after 20 consecutive days,she looked for cheaper alternatives in parks,KFC restaurants,and milk tea shops.

A friend finally told her about the National Library in Beijing,which attracted her because it was “free,air-conditioned,and quiet,” Su tells TWOC.

The modern public library is widely believed to have originated with the Boston Public Library,which was founded in 1854 with the aim that every citizen had the right to access free community services and to educate themselves.China’s first library under this model,different from the imperial archives and private stacks that existed for much of the country’s history,was either the Boone (or Wenhua) Library started in Wuhan by American educator Mary Elizabeth Wood in 1910,or the Hunan Public Library in Changsha,built by entrepreneur Liang Huankui (梁焕奎)and government official Zhao Erxun(赵尔巽) in 1904.

During the Republic of China,besides missionary-founded libraries in major eastern cities,it was fashionable for renowned intellectuals to sponsor libraries in their hometowns.The Communists also operated libraries in their base areas in the Northwest in the 1940s for grassroots ideological,cultural,and scientific education.Some of these libraries hosted lectures,exhibitions,and other activities aimed at eradicating illiteracy.

Libraries are becoming popular choices for people to kill time with free internet access and air conditioning

Many of the country’s current public libraries were built after 1978,when scientific research was high on the agenda amid China’s market reforms.Until 2011,when the Ministry of Culture stipulated that museums and public libraries at the national or provincial level ought to be free to enter,many charged fees for services like looking up reference material or computer use.In 2017,the new National Public Library Law stipulated that several types of service should be provided free of charge for all:inquiries and borrowing,public reading rooms,and access to public lectures,training,and literacy promotion.

By this time,the role of libraries in serving socially vulnerable people was already well-understood by the public.In 2016,the Hangzhou Public Library in Zhejiang province announced that homeless people were welcome to use its services.When some locals complained that these patrons smelled and looked “too ragged,”the library’s director Chu Shuqing famously responded,“I don’t have the right to keep away beggars and scrap collectors,but if you disagree,you have the right to leave.”

Other libraries followed suit and since then,a number of high-profile incidents have entrenched libraries in the public imagination as the standardbearers for inclusivity and equality in China.Last July,the Zhengzhou Library in Henan province stayed open 24 hours a day for several days to provide shelter for people hit by the devastating floods in the province.In 2020,an article in Portrait magazine recounted the story of a woman with a young daughter who lived in the Dongguan Public Library in Guangdong province for a week,possibly as an escape from domestic violence.

Wu Jun (pseudonym),a 30-year-old scrap collector from Anhui,reads books in the Hangzhou Public Library until closing every day

Earlier that same year,the Dongguan Library had gone viral when a migrant worker named Wu Guichun wrote a touching farewell message in its guestbook.Wu had been a voracious reader at the library for 12 of his 17 years in Dongguan,but was reluctantly returning to his hometown as factory work dried up during the pandemic.“Books teach you wisdom.They are the only things in the world that are totally good,” Wu wrote in his message,later telling journalists he chose to spend all his spare time in the library because it was free and airconditioned,and that the staff didn’t ask for ID or bother him even when he ate amid the stacks.“I will never forget this place as long as I live.”

Besides the use of their space,public libraries are also increasingly taking on bigger roles in the community by offering free public lectures,training courses,and of course,access to books themselves.Since 2011,the Library of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region in Nanning has invited experts to give lectures for unemployed people and migrant workers.In 2019,Shiyan Library in Hubei province hosted a free summer camp where the children of migrant workers could take computer classes and watch movies.From January to February of this year,migrant workers could go to Chongqing’s public libraries for help buying train tickets ahead of the Lunar New Year holidays.

Xu Pan,who works in the publicity department of Yuexi County Library in Anhui province,tells TWOC that there are several tables in her library reserved for seniors and since 2013 they have offered free classes on calligraphy,chess,and other subjects for primary school students.In the Sanming City Library,Fujian province,there are health care lectures for elders and reading classes for children with visual impairments.

Xu tells TWOC that the library has worked hard to minimize disruption while keeping the space open for all visitors.There are readers with intellectual disabilities,who will sometimes drink out of other people’s bottles or shout,but “librarians will pay special attention to these readers and stop them when warning signs occur,and no one has yet complained about them.”

However,not all libraries and patrons have been equally open about who can enter or borrow.In 2013,a library in Zhengzhou introduced a controversial rule that stipulated children under 14 were not allowed to enter as they made too much noise.The National Library in Beijing has also courted criticism since 2008 by only allowing readers above a certain professional level or who hold a postgraduate degree to borrow foreign language books and certain Chinese language books.

A free computer class for senior citizens at a public library in Mianyang,Sichuan province

There is also disagreement among experts on whether libraries ought to become all-purpose community centers,or focus more on public education.A 2019 op-ed from media outlet East Day called sleeping in libraries “uncivilized behavior.” “From the perspective of promoting public literacy,as soon as people walk into the library,they ought to be intoxicated by the atmosphere of reading and develop the habit of reading,” wrote the author,who suggested librarians should wake and warn sleepers.

Shangguan Xiaomin,a librarian from Fujian’s Sanming City Library,is critical of these attitudes.“Our directors tell us that anytime a person enters the library,they are our reader and can do whatever they want[without disrupting others],” she claims.Wang Yanjun,the Dongguan librarian who publicized Wu Guichun’s story,told Portrait magazine that the library attracted a lot of criticism for putting “Relaxation” first in its motto,“Relaxation,Interaction,Knowledge.” But Wang felt it was well-suited to Dongguan,which has a large population of migrant workers with little education,and felt that some visitors may be encouraged to pick up a book after they’ve enjoyed the airconditioning and seats for a while.

However,there are still psychological barriers preventing less-educated people from making full use of libraries’ services,or even being aware of them.In another library in Dongguan,26-year-old librarian Liang Nüsheng remembers several migrant workers in their 40s who came to read,but never borrowed any books,which she attributes to shyness and feeling intimidated by the lending process.“The most important thing is to build an equitable atmosphere and let these disadvantaged people know they have rights to get services,” she tells TWOC.Xu had similar experiences in Yuexi:“A lot of people think libraries are for intellectuals and charge fees for reading,so they are ashamed to come in,just like when[middle-class people] see luxury shops.”

Growing demands from readers have led to libraries trying to expand their services.Each July and August since 2018,Xu’s library has extended its opening hours from 5 p.m.to 9 p.m.to cater to students who come to study during their summer vacation.The library had previously wanted to offer 24-hour services,but this plan foundered due to a lack of staff,facilities,and funding.“It’s not that simple,” Xu explains.“We need to hire people to take the night shift.We need desks,chairs,beds,and more space.Who will give us the funding?”

At the start of the pandemic,libraries nationwide shut their doors.Since then,many have limited their visitor capacity and moved parts of their services online.Xu’s library removed half of its chairs for social distancing and asked visitors to make appointments.Su,in Beijing,tells TWOC that she sets several alarm clocks to remind her to reserve an entry slot as soon as the system opens,but sometimes the spaces are booked out in just five minutes.In addition,mandatory health code and occasional ID checks since the pandemic began have eroded some of the openness of many libraries.

Libraries in suburban and rural areas also fall short.Though the government made constructing rural libraries a priority in 2021,many towns and villages still only have mobile libraries at best.Residents of Yanjiao,a satellite town of Beijing in neighboring Hebei province,have demanded a public library for years,but were finally told by the local culture bureau in 2020 that Yanjiao’s urban classification does not meet the“requirements” to qualify for a library at this time.

For Xu,libraries are indispensable public spaces,and her goal is to make them truly public.“For some,there is still an invisible wall that holds them back from libraries,” she says.“[My question is],how can we help poor and illiterate people become confident enough to enter libraries?”

Perhaps the best attribute of public libraries is that you don’t need to be seeking any higher purpose to use them—or to be seeking anything in particular at all.“[At first] I was always curious why there were so many young people here every day.Don’t they have to work?” says Su.“Now I know everyone is just like me,taking a brief break from their troubles in the corner of the library.”

——YANG TINGTING(杨婷婷)

FOR THE DOWN-ON-THEIR-LUCK OR VULNERABLE,THE LIBRARY CAN BE AN ESCAPE FROM OVERCROWDED LIVING CONDITIONS,OR EVEN A SHELTER FROM DOMESTIC VIOLENCE AND NATURAL DISASTERS IN A NATION WHERE SUCH FACILITIES ARE STILL IN SHORT SUPPLY.

ILLUSTRATION AND DESIGN BY CAI TAO AND XI DAHE

OFF THE LEASH

Dog ownership in China is booming,but finding inclusive spaces for animals remains a tall order in most cities

Ever since Su Shan adopted Tangdou,a miniature poodle puppy weighing around 4 kilograms,just over a year ago,she feels she has “said goodbye to most forms of public transportation.”

That’s because in Qingdao,the picturesque seaside city in eastern China’s Shandong province where Su lives,dogs are banned from public transport (and taxis without the consent of the driver);as well as libraries,museums,memorial halls,sports venues,beaches,government offices,hospitals,and schools.

Even where there are no specific regulations,Su has been turned away from restaurants and farmers’ markets for bringing her dog,and has gotten used to calling up various venues to ask if Tangdou is allowed before she visits—and getting rejected.“Even when I put a leash and a diaper on her,a lot of people object,” Su tells TWOC.“They think the dog will attack,no matter its size.”

Dog ownership in China has boomed in the last two decades:There were 36.2 million people with dogs in 2021,according to a study by research firm Pethadoop,an increase of 260,000 from 2020.Businesses designed for doggy friends have flourished in tandem:Today,China’s pet food industry alone is worth a whopping 200 billion yuan.

But pet-friendly infrastructure in busy cities have failed to keep up.Chengdu,the capital of Sichuan province,has long limited each family to owning just one dog.Lawmakers in Zhengzhou,capital of Henan province,announced their intention to follow suit in 2021.In Beijing,dogs have never been formally given access to the city’s parks,only allowed into designated pet parks (although this was loosely enforced until 2018).Guangzhou,Guangdong province,has a string of regulations:from the places in the city where dogs can’t go,to what lengths of leash are required depending on the dog’s weight.

Many pet-owners and experts TWOC spoke to attribute this gap to the relatively short history of petownership in China,compared to centuries of history where most of the population saw animals either as resources to be used on farms or pests to be eliminated.Before the Cultural Revolution,dogs “were more known as guard dogs and working dogs…instead of the companions we see today,”Mary Peng,CEO of the International Center for Veterinary Services,a private animal hospital in Beijing,tells TWOC.“They were meant to bebig and aggressive,and that image stayed with the common psyche in China,” Peng says,explaining why some urban residents remain wary of dogs roaming their cities,and will even give pet dogs a wide berth if they encounter them in the streets.

Pet-owners often have to drive hours out of the city to find spaces where their pets can roam

Chinese laws and regulations on dogs and pets first emerged in the 1980s,when pet ownership began to increase.But an outbreak of rabies in 1981,attributed mainly to dog bites,led to the implementation of stricter measures to regulate stray dogs and push vaccinations to curb the disease.Up to 1993,dogs were simply banned from cities.These rules were updated that year,allowing urbanites to keep dogs if they registered them for 5,000 yuan.

As pet ownership increased,the price of registration fell to 1,000 yuan in 2003.Beijing’s rules on pet dogs have remained the same since that period:A dog should always be on a leash,even if it’s in a designated dog park.Only one dog can be registered for each household.Owners cannot walk their dogs during business hours(7 a.m.to 7 p.m.),and no dogs over 35 centimeters at shoulder height are allowed inside the Fifth Ring Road.Large dogs and breeds considered by some people as aggressive,such as Rottweilers and German Shepherds,are banned in Beijing and Shanghai.

In early 2019,Beijing started tightening up the rules due to growing complaints from its residents about dogs roaming freely and littering in parks,and enforcing previously lax registration requirements for pet dogs,in part due to rabies outbreaks in 2020.“If your dog is not registered,it’s automatically considered a stray.So,it has no protection if anyone decides to lodge a complaint and you will lose your dog to the authorities,”Peng tells TWOC.

Other cities have even stricter rules.Hangzhou,a large city in eastern China,introduced a daytime dogwalking ban in 2018.In November 2020,after receiving complaints of dogs biting children in Weixin county in Yunnan province,officials said they would ban dog walking in urban areas completely,and put in place a harsh three-strike penalty system:a warning for those caught walking their dogs the first time,a fine on the second strike,and the third time,the public security bureau would be sent to capture and kill the dog.The rule was later rescinded amid national and international furore.

For Su,these rules are not huge inconveniences.“I always put my dog on a leash,and I think [most people]are rule-abiding,” she says.However,she thinks her city is “not at the level yet” where everyone will abide by the rules on leashing dogs and picking up after them.

Fu Lin,a dog-owner in Linfen,a relatively small city of under 1 million people in northern China’s Shanxi province,agrees,but adds that she feels there are also people who use the rules to simply vent their prejudices about animals.“We always put our dogs on a leash,because we feel like that’s the right thing to do,but there are still people who will curse at us and say we’re breaking the law,” she complains,adding that she usually walks Eva,her 21-kilogram giant poodle,at midnight to avoid such conflicts.

“It is socially acceptable for people in Shanghai to dislike dogs,”says Nicoco Chan,an American photographer and videographer(and frequent TWOC collaborator)in Shanghai who owns two dogs,both under 7 kilograms.“This is a complete contrast to the US,where disliking dogs is a social sin that’s even been incorporated into pop culture,”she says,citing the sitcomFriends,where the character Chandler’s dislike of dogs is treated as a joke.Chan has had many experiences of being asked to move out of people’s way on sidewalks when out with her dogs,and mentions a particularly memorable episode when a woman began screaming as soon as she saw Chan’s dog in a cafe,and had to be escorted out by staff.

“Though the older generation may have had a traumatic or frightful experience with a dog,for younger generations I suspect it is a learned behavior,” Chan believes.“It is very common for a parent to pull a child away from my dog while warning the child ‘careful,it will bite you.’”

Pet-friendly group outings organized by pet-owners are a stress-free (though costly) method for finding recreation for pets

For pet-owners,these cultural attitudes limit where they can go with their dogs.Chan says there are some dog-friendly cafes in Shanghai,but not many outdoor spaces where dogs are not banned—just a small enclosed section in the West Bund where dogs can be let off their leashes.A 37-yearold Beijing dog-owner,who preferred to be called Shan,tells TWOC that she and her three-legged rescue dog,Lucky,have been rejected by drivers on ride-hailing app DiDi on multiple occasions,with drivers worried about cleanliness and smells that might put off future passengers (thus influencing their ratings in the app),and wary the dog might become aggressive.

Some cities are taking measures to cater to their growing population of dog owners.As early as 2011,Panyu district of Guangzhou announced it would invest 280,000 yuan into building dog-walking spaces,and set up pilot areas in several parks and neighborhoods with dog toilets and exercise spaces cordoned off from the rest of the area.Parks in Zhuhai,Liwan,and other districts also set up designated dog areas,though TWOC couldn’t find any follow-up on several such projects in the pipeline.Across the bay in Hong Kong,authorities announced this year they will add 60 dog parks to the Special Administrative Region,bringing its total number to over 100.

DiDi also piloted “specialized pet taxis” in Beijing in March and April of this year,with drivers hailed through this service providing special accommodations to passengers with pets.Traveling longer distances remains a challenge,with many owners resorting to hiring a taxi or specialized pet transport company—as pets must ride in the cargo area on trains,planes,and the high-speed rail.“I’ve read lots of negative news about pets being hurt while being transported in cargo areas,so I’m very anxious about traveling [with my dog],” says Fu.“Because of this,I might choose not to go on a trip.”

In most cities,pet owners have to make do with what little slack authorities give them.Some owners of large dogs form group chats informing each other of the best times and areas to walk their dogs without running into law enforcement officers,and other dog-owners gather in designated open areas that the neighbors tacitly acknowledge to be unofficial dog parks—and that they and local authorities are mostly willing to tolerate,as long as the dogs don’t create any disturbance.

Shan mentions a “secret spot” she goes to next to Beijing’s Liangma River,a rare open park and river area in the city,to socialize with other dogowners,but says it has recently been shut down by the pandemic.Across China,pandemic measures have highlighted the lack of inclusion for pets in urban policies as well as societal attitudes:There were reports of pets being culled allegedly for disease-prevention,and Chan reports that Shanghai’s lockdown in the spring was “crazy stressful”for pet-owners like her,some of whom spent up to 2,000 yuan to move their dogs to a shelter if they got taken to quarantine.There were some cities like Shenzhen that set up pet quarantine hotels,but they remained the exception rather than the norm.

Urban management officers sometimes also patrol parks and streets to curb “uncivilized” dograising behavior

Chan says that people’s concerns about strays and irresponsible owners who do not vaccinate,train,or pick up after their dogs are“absolutely valid issues,” though she hopes more people can separate their criticism of owners from a rejection of dogs overall.

She feels that regulating pet shops to make sure they vaccinate their animals (as many sell puppies before they are old enough for their shots,for maximum cuteness),and pushing owners to vaccinate and register their dogs,could be a step toward removing the issues underlying some people’s fears.Similarly,Fu suggests creating more designated dog parks,and Su believes that outlining rules for how dogs ought to ride public transportation and long-distance trains—such as having a leash or muzzle—would be more humane than a one-size-fits-all ban.

“Overall,the issue is with a lack of experience and knowledge,” Chan says.“Kids are naturally fearless,so it’s too bad many of them end up being scared of dogs.”