Opportunities for Foreign Investors in Vietnam’s Coffee Industry

Timothy Standen

Vietnam is the second-largest exporter of coffee after Brazil, accounting for 8.3% of the global coffee share and 16% of the market share in the EU. However, the majority of exports remain in the form of unprocessed beans and little added valuation.

Despite the pandemic, Vietnam’s coffee industry saw over US$ 3 billion worth in coffee export revenue in 2021, which accounted for 3% of the country’s GDP and 10% of its agricultural exports. As the country looks to step up its coffee processing industry, total exports are expected to reach US$ 6 billion by 2030.

The coffee bean was first brought to Vietnam in 1857 by French colonialists who discovered that the environmental conditions in the country’s central highlands were suitable for the cultivation of many foreign crops. The French originally brought the Arabica variety; in 1908, the high-yield Robusta variety was introduced and cultivated alongside Arabica.

In 1986, after the reunification of Vietnam, the Doi Moi (renewal/new age) reforms to the economy saw increased privatization of land and commodities. The government saw potential in coffee as a cash crop for exports as well as domestic use thus introducing state-funded farms while also encouraging families with land to cultivate coffee within the Central Highlands.

As a result of these accumulated practices, the Vietnamese coffee industry is now facing several challenges — aging coffee trees, small-scale and fragmented production, and effects of climate change. This presents opportunities for investments into the sector — in areas that could see Vietnam climb up the global coffee value chain.

Vietnam’s high-yield coffee Robusta bean production

Some 95% of the coffee produced in Vietnam is from Robusta beans compared to just 5% from Arabica.

When introduced in 1908, Robusta was found to thrive in lowlands, providing a higher yield of bean per hectare. It could grow at altitudes of 200-700m above sea level and be found to be less susceptible to diseases.

Between 1989 and 1995, the Vietnamese government-controlled coffee exports by purchasing coffee beans from all farmers at set prices. The low prices for coffee beans pushed farmers into growing Robusta as their main cash crop, thereby making Vietnam the world’s largest producer of Robusta beans. Robusta currently is estimated to provide 2.8 tons of coffee bean yield per hectare.

What are the challenges facing Vietnam’s coffee industry?

Although Vietnam’s coffee industry has fared well over the past decades, the industry faces a multitude of challenges that are hindering its progress up the value chain.

Highly fragmented industry

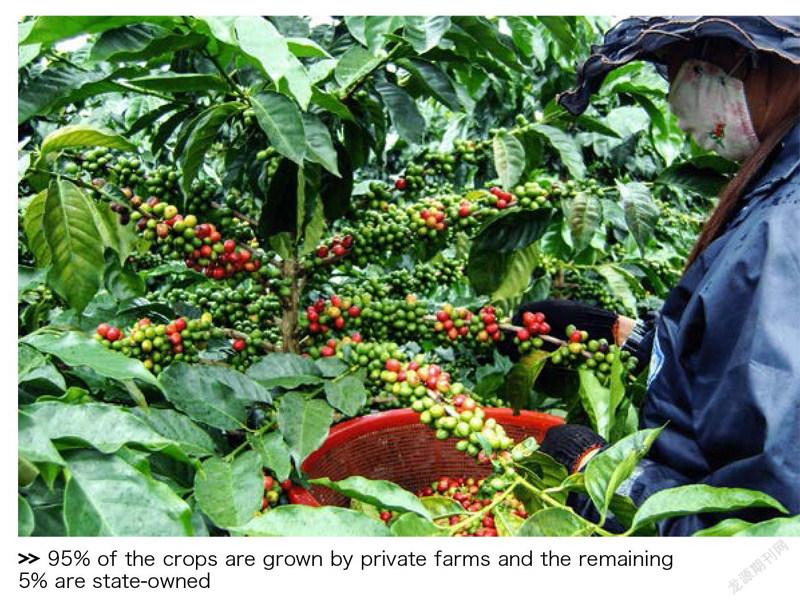

Vietnam’s coffee industry is highly fragmented — today, 95% of crops are grown by private farms and the remaining 5% are state-owned. The majority of the current private farms are owned by smallholder farmers, equating to approximately 650,000 families cultivating coffee with approximately one hectare of land.

Such small-scale production, fragmentation, and the dependence of farming households have produced differences in investments, harvesting, and processing methods between farmers, resulting in unreliable output and uneven quality of products.

Lack of modern infrastructure and equipment

Though Vietnam has invested heavily into its coffee industry — now comprising of 160 coffee roasting facilities, 11 coffee blending facilities, and 8 instant-coffee processing facilities with a total processing potential of 1.5 million tons — the industry lacks updated modern infrastructure and equipment.

The majority of coffee roasting facilities consist of using tarps to sundry the coffee beans. This basic way of roasting/drying the coffee beans can lead to a drop in quality, especially during Vietnam’s rainy season. To move up the coffee value chain, Vietnam needs to improve its coffee processing infrastructure.

Unsustainable farming techniques and climate change

Irrigation is essential for coffee farms to achieve high yields and make cultivation profitable. This is particularly important during Vietnam’s dry season between January and April and therefore farmers resort to using groundwater.

However, this threatens the long-term sustainability of Vietnam’s coffee industry as groundwater becomes depleted. Wealthier farmers tend to build basalt aquifers made through borehole drilling, which has contributed to the depletion of groundwater and soil degradation.

Moreover, the threat of climate change can exacerbate this problem. For instance, Vietnam’s dry months could last longer, requiring farmers to use more groundwater resources. It could also lead farmers to migrate to higher altitudes to access the suitable conditions to grow coffee; however, such migration could also increase deforestation in areas where forests provide vital watershed protection.

Aging coffee trees

More than 30% of Vietnam’s coffee trees are between 20 and 30 years old and are beyond their peak productive age, which is usually between eight to 15 years old. Research suggests that after 22 years, the coffee tree becomes economically unviable.

Farmers would need to cut and replant new trees, often a significant investment for smallholders, especially since they would need to wait four to five years for the tree to bear fruit.

Moving up the coffee supply chain

Vietnam must invest in its coffee value-added industries to move up the global coffee supply chain and make the industry more sustainable; processed coffee currently makes up less than 10% of the country’s total coffee production. This presents ample opportunities for foreign businesses, especially those with expertise in the production of processed coffee products. The Vietnamese coffee industry wants to meet its target of reaching US$ 6 billion in exports by 2030. The industry would also need to increase its yield of coffee beans without further deforestation by improving the efficiency and consistency of current plantations.

Government incentives and support

Vietnam’s coffee industry requires a linkage for raw material areas with processing facilities, creating a stable supply of goods that can meet market requirements. Further, the government is eager for Vietnam’s agriculture industry to apply automation, biotechnology, and information technology to boost sustainability. For instance, enterprises that invest in scientific research and technologies to serve production and business in agriculture will receive state support in the form of low-interest loans. Research in coffee bean varieties could result in coffee that is more resilient to adverse conditions such as droughts.

By investing in Vietnam’s coffee processing sector, foreign businesses can benefit from the plentiful availability of raw materials, a large domestic market, and tax breaks through Vietnam’s large number of free trade agreements and government support.

A growing domestic coffee market

The signing of the EU-Vietnam Free Trade Agreement offers great opportunities for Vietnamese brands to export their processed coffee products to the EU. Building local brand names will raise quality standards and enable Vietnamese coffee brands to better compete in the international market.

Further, despite the COVID-19 pandemic, Vietnam saw an increase in the number of new coffee shop chains, a testament to a growing middle-class population with increasing purchasing power. According to Euromonitor International, the country’s specialty coffee and tea shops are worth more than US$ 1 billion, with local chains expanding faster and performing better than their international rivals. Local coffee chain The Coffee House already has 125 stores in the country, with ambitious plans to expand to 1,000 by 2025. Starbucks, which has been in Vietnam since 2013, only has 77 outlets throughout the country.

While foreign brands dominate the high-end segments, local brands dominate the mid-range and low-price segments. Local brands are also able to adapt to new trends faster and have a larger footprint in the country.

Source: ASEAN Briefing

The article only represents the author’s views, not the stand of the magazine