Sudden unexpected infant death rates and risk factors for unsafe sleep practices

Balkissa S.Ouattara ·Melissa K.Tibbits·Drissa M.Toure·Lorena Baccaglini

Sudden unexpected infant death (SUID),the leading cause of death in the post-neonatal period in developed countries,represents the death of an infant less than 1 year of age that is sudden and unexpected [1–3].SUID is a general term that encompasses the following:sudden infant death syndrome(SIDS),accidental suffocation and strangulation in bed,and unknown causes of death in infants less than 1 year of age[4,5].Infant unsafe sleep practices,including co-sleeping,non-bed sleep,soft bedding use,and non-back sleep,are reported as risk factors for SUID [4,6,7].

This study’s objectives were to calculate SUID rates from 2008 to 2017 and assess the determinants of unsafe sleep practices in Douglas County,Nebraska.Douglas County is the most populated of the 93 counties in Nebraska.According to the 2020 United States Census,the County counts 584,526 people [8],and the racial distribution of the County was:White (68.8%),Black or African American (11.5%),Native American (1.2%),Asian (4.3%),Pacific Islander (0.1 %),two or more races(2.8%).Hispanic or Latino of any race represented 12.9%of the population [8].Furthermore,the Douglas County Health Department (DCHD) hosts the FIMR program,an interprofessional community-based program that identifies infant mortality risk and protective factors through the review of fetal and infant death cases.The FIMR program uses the following procedures to improve infant health in Douglas County [9].

(1) Data collection:all infant deaths in Douglas County are reported to the Vital Statistics Department,which conducts a complete investigation of all SUID cases,including an autopsy and a death scene investigation.The investigated cases are then sent to the DCHD FIMR program.The FIMR program public health nurse gathers additional information from hospital records and interviewing the mothers of loss;(2) case review:a team of medical,public health,and community experts meets monthly to review case information summaries to identify risk and protective factors and make recommendations for system changes;(3) community action:the recommendations made by the case review team are used to implement interventions through the community action plan.

A retrospective longitudinal study was conducted.The study population was represented by all live births in Douglas County,Nebraska,from 2008 to 2017.All 62 infants (paired with their mothers) who died of SUID from 2008 to 2017 were included in the study.

Secondary de-identified SUID data were obtained from the DCHD FIMR database and live births data retrieved from the Vital statistics website [10].Because all data in this research were aggregated and de-identified,the Institutional Review Board of the University of Nebraska Medical Center classified the study as exempt.

Outcome variables:co-sleeping,non-bed sleep,soft bedding,and non-back sleep were the binary (yes/no) outcome variables used in this study.

Independent variables:the independent variables included the infant’s age at death in months (0–6 vs.>6 months) and his gender,the mother’s age (<25 vs.25 years or older),the mother’s race (White vs.non-White),breastfeeding,and marital status.The other independent variables were Medicaid (if the mother was a beneficiary or not),high school diploma (whether the mother had a high school diploma or not),and secondhand smoke (whether the mother or other household member smoked during or after the pregnancy).

SUID rates were obtained by dividing the number of cases in each period by the number of live births during the same period per 100,000 live births.SAS software version 9.4 was used to performed descriptive statistics and logistic regression analysis.A logistic regression analysis of each independent variable was conducted for each of the four outcome variables.

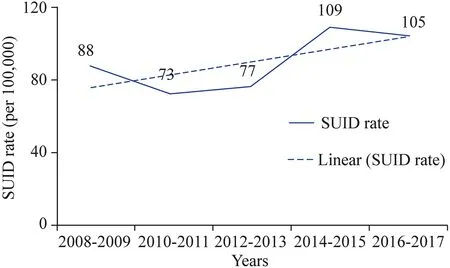

The average SUID rate during the study period was 90 per 100,000 live births.The rate’s trendline showed an increase(Fig.1).

Fig.1 Biannual sudden unexpected infant death (SUID) rate per 100,000 live births and trendline in Douglas County,Nebraska from 2008 to 2017

The mean age (months;± standard deviation) for infants was 3 ± 2,with most SUID death occurring before the age of 6 (92%) months.More than half of the mothers were White (55%),and Medicaid recipient mothers represented approximately ¾ of the sample.African American mothers represented 35% (22/62) of all mothers and about 80%of non-White mothers.More than 90% of the study participants practiced at least one unsafe sleep behavior.The most adopted unsafe sleep practice was the soft bedding use followed by the non-bed sleep and co-sleeping.The practice of co-sleeping was about 40% more common among non-White versus White mothers,and 40% more common among Medicaid beneficiaries compared to mothers with private health insurance.Similarly,non-bed sleep practice was about 40% more common among non-White compared to White mothers,and 45% more common among Medicaid recipients (Table 1).

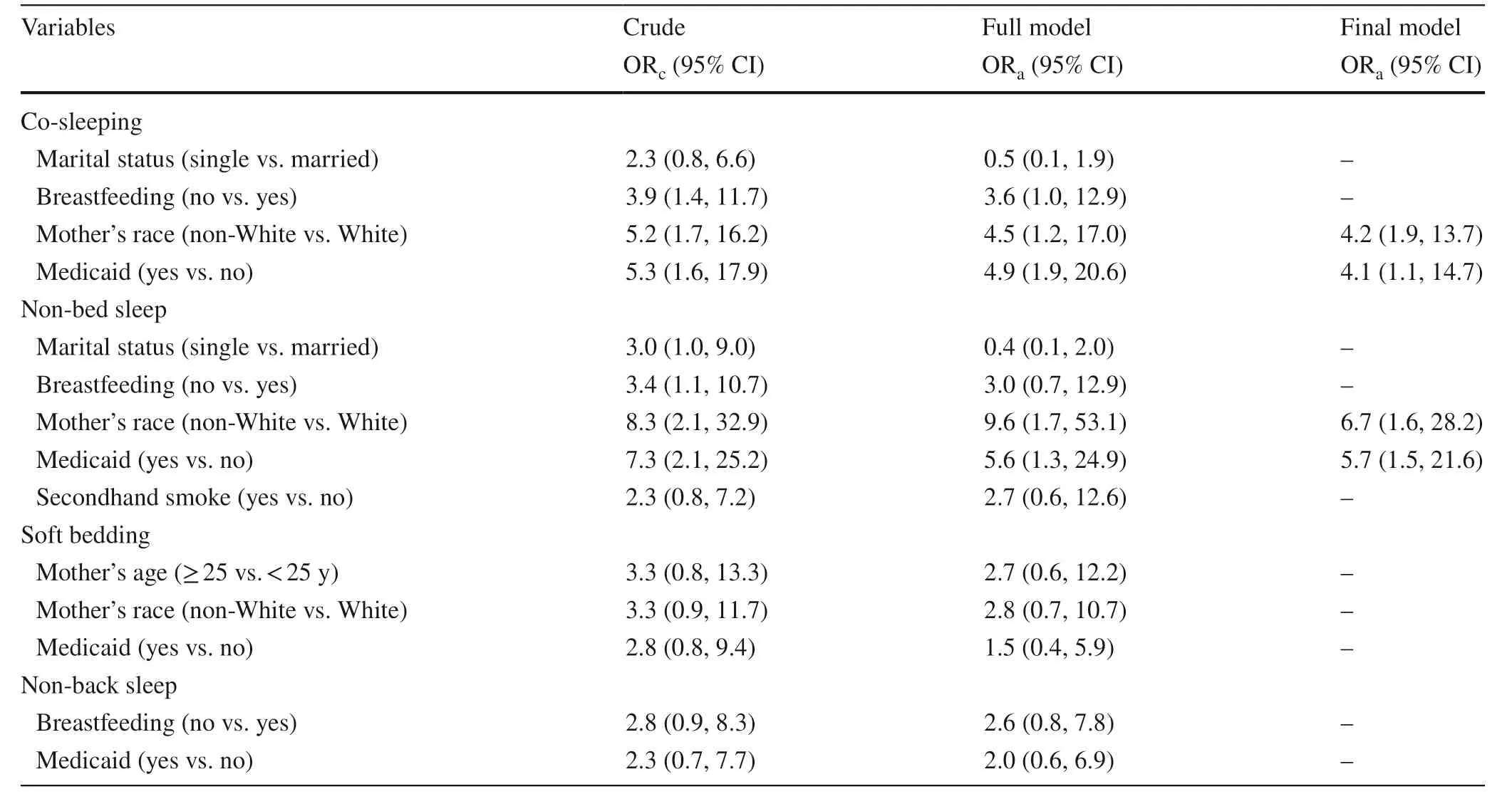

After adjusting for all covariates in the model,the odds of After adjusting for all covariates in the model,the odds of co-sleeping were 4.2 times higher [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.9–13.7] for non-White vs.White mothers.Also,Medicaid beneficiary mothers had 4.1 times higher adjusted odds (95% CI 1.1–4.7) of practicing co-sleeping.After controlling for all four covariates (marital status,breastfeeding,Medicaid,and secondhand smoke),the odds of infant non-bed sleep were 6.7 times higher (95% CI 1.6–28.2) for non-White vs.White mothers (Table 2).

Table 1 Determinants of unsafe sleep practices among sudden unexpected infant death cases

Table 2 Association between socio-demographic characteristics and unsafe sleep practices among sudden unexpected infant death cases

Overall,SUID rates in Douglas County,Nebraska had increased from 2008 to 2017.These rates are higher than the Healthy People 2020 goal of 84 per 100,000 live births[11].The mean age of infant death in this study was 3 months,and about 92% of deaths occurred before the age of 6 months.The age range of zero to 6 months is highlighted in the literature as a critical period for SUID occurrence[6,12] and should be used as a window of opportunity to reinforce the American Academy of Pediatrics safe sleep recommendations.

Mother’s race was associated with co-sleeping.Indeed,non-White mothers in our study,consisting of 80% of Black mothers,had four times higher odds of sharing a bed with their infants than White mothers,which corroborates previous findings that the black race was associated with bed-sharing behavior [13–16].Critical reasons for noncompliance to the safe-sleeping recommendations by non-Whites mothers (mostly Blacks) may include convenience,perceived safety,and familial and cultural influences [13,17].

Being a Medicaid recipient was also strongly associated with co-sleeping.Medicaid was used as a proxy for socio-economic status since only low-income mothers(more than 150% below the Federal Poverty Level) qualified for state insurance [18].The association between co-sleeping and low-socioeconomic status (SES) has also been reported by Norton and Grellner [19].Black race and SES are described as risk factors for SUID by Adams et al.[6].

In conclusion,prevention efforts should target those at highest risk and focus on educating parents and caregivers to provide a safer sleep environment.Public health leaders and policymakers may consider developing culturallyadapted social marketing messages on infant safe sleep targeting new parents,grandparents,and other caregivers.Venues such as Women Infant and Child (WIC) clinics for low-income mothers may be used to disseminate and promote infant safe sleep messages,since most mothers receiving Medicaid insurance are also eligible for WIC benefits.

AcknowledgementsThe research team acknowledges the Douglas County Health Department for allowing access to the data,and particularly Carol Isaac,the FIMR program coordinator,for helping understand and better exploit the data.The team is grateful to the FIMR case review team for their determination in finding preventable gaps in infant death and suggesting action plans to address such deaths.

Author contributionsAll authors contributed to the study conception and design.OBS contributed to data collection,data analysis,and wrote the first draft of the manuscript.All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript.All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

FundingNo financial or non-financial benefits have been received or will be received from any party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Data availabilityThe data that support the findings of this study are available from the Douglas County Health Department,Nebraska but restrictions apply to the availability of these data,which were used under agreements for the current study,and so are not publicly available.

Ethical approvalBecause all data in this research were aggregated and de-identified,the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of Nebraska Medical Center classified the study as exempt.

Conflict of interestAll authors report no conflict of interest concerning the content of the present manuscript.

World Journal of Pediatrics2022年3期

World Journal of Pediatrics2022年3期

- World Journal of Pediatrics的其它文章

- Information for Readers

- Editors

- Instructions for Authors

- Limited value of procalcitonin,C-reactive protein,white bloodcell,and neutrophil in detecting bacterial coinfection and guiding antibiotic use among children with enterovirus infection

- Towards creation of national cerebral palsy registries in Arab countries:what is missing?

- Occurrence of early epilepsy in children with traumatic brain injury:a retrospective study