Fatal progressive ascending encephalomyelitis caused by herpes B virus infection: first case from China

Tian-peng Zhang , Zhen Zhao, Xue-lian Sun, Miao-rong Xie, Feng-kui Liu, Yong-bo Zhang, Lu-xi Shen, Guo-xing Wang

1 Department of Emergency, Beijing Friendship Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing 100050, China

2 Department of Neurology, Beijing Friendship Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing 100050, China

Corresponding Author: Guo-xing Wang, Email: wangguoxing1@ccmu.edu.cn

Dear editor,

Herpes B virus (BV), also known as Macacine herpesvirus 1 (family:, subfamily:, genus:), officially designated by the International Committee on the Taxonomy of Viruses, exhibits serologic cross-reactivity with other members of the genus, namely HSV type 1 (HSV-1), the causative agent of oral herpetic ulcers (cold sores) in humans and HSV type 2 (HSV-2), the agent of human genital herpes.BV infection in macaques is life-long, with periodic reactions, sometimes causing HSV-like symptoms; however, it may cause fatal encephalomyelitis in humans.Primates (predominately rhesus monkeys and longtailed macaques) have been extensively used in research as translational models for human diseases since the 1930s. Exposures are routine in veterinarians, laboratory researchers, and animal care personnel working with macaques. Humans typically acquire BV infection by direct bites or scratches from macaques or contaminated materials (e.g., needle stick wounds, dirty cages, primary cells preparations, mucus splashing).Although there were many exposures from macaques in research, documented zoonotic BV infection cases are rare. However, the mortality rate could be 70%-80% if exposure is not promptly evaluated and treated. For those who survive, neurological impairment and further deterioration of neurological function are common.

CASE

A 53-year-old man was admitted after resuscitation from a cardiac arrest on April 13, 2021. He was a veterinarian occupied primarily with the inoculation of(rhesus) in a local experimental animal care facility. Six days before his admission to hospital (on April 7), he developed a fever (peak temperature 40 ℃) accompanied by chills, dizziness, fatigue, anorexia, and myalgia. On April 10, he complained of headache, gradually-worsening unsteady gait, and vague intermittent pain behind the sternum. He consulted a physician at a local hospital. However, routine laboratory investigations (complete blood cell count, urinalysis, and serum biochemistry) revealed no abnormality. He was prescribed lysine acetylsalicylate as antipyretic and piperacillin/tazobactam sodium as antimicrobials. However, there was no respite in fever.

On April 12, the patient’s symptoms worsened, and he developed limb weakness and persistent retrosternal pain. He went to another hospital for further treatment. Laboratory examination at admission revealed no obvious abnormalities except for elevated troponin I (TnI) 0.044 ng/mL (reference range: 0-0.03 ng/mL), myoglobin 138 ng/mg (reference range: 0-46.6 ng/mg), and negative epidemic hemorrhagic fever antibody. His brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) were normal. No medication was prescribed.

At 17:35 on April 13, the patient suddenly developed respiratory and cardiac arrest during the consultation in the outpatient department of tropical disease, Beijing Friendship Hospital, Capital Medical University. The electrocardiogram showed a ventricular escape beat. He was immediately resuscitated, intubated, and placed on mechanical ventilation. At 17:50, he was administered asynchronous electrical defibrillation three times (200 J) because of ventricular fibrillation. After 20 min, the cardiac rhythm was restored; however, large doses of norepinephrine were required to maintain the blood pressure. Echocardiography showed an enlarged left ventricle, with a reduced motion of the left ventricle’s anterior, lateral, and inferior walls; the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was 33%. Neurologic examination showed a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 3, bilaterally symmetrical circular pupils, and absent light reflex. There were no signs of meningeal irritation or pathological reflexes. The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) on April 14 for advanced life support.

Empirical antibiotic therapy with meropenem was started on the first day after admission. All microbiologic test results for blood and bronchoalveolar lavage were negative. During the early days in ICU, he developed multiple organ dysfunction syndromes (MODS) involving the brain, kidney, liver, and coagulation system. Some of these functions were ameliorated by advanced organ support treatment. However, repeated head CT showed severe cerebral edema, suggestive of ischemic-hypoxic encephalopathy. Moreover, the electrocardiogram (ECG) showed depressed ST segments in leads II, III, and aVF, with no pathological Q wave. TnI and myoglobin dropped to normal within three days.

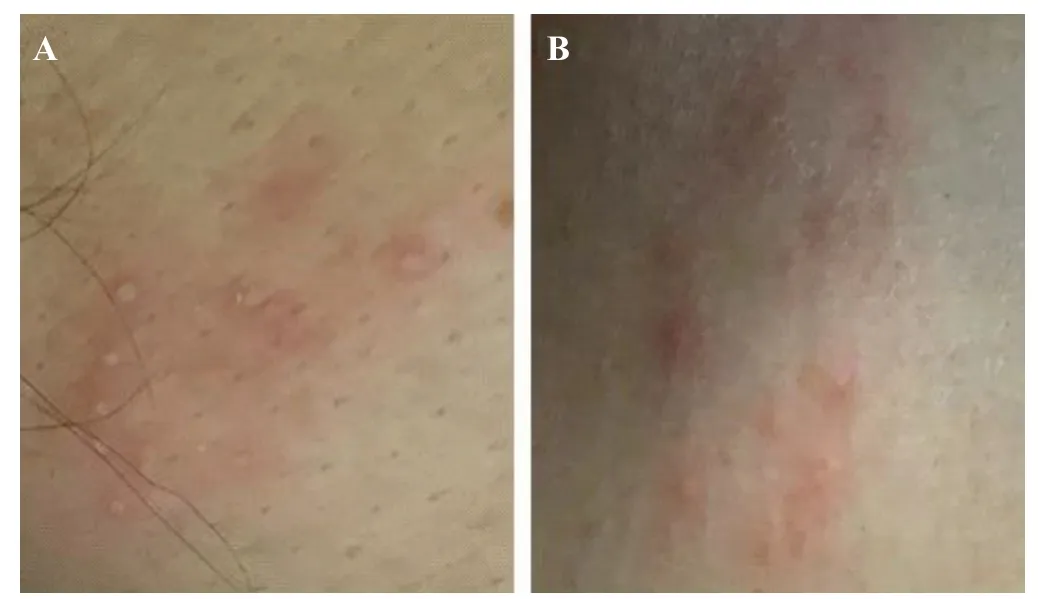

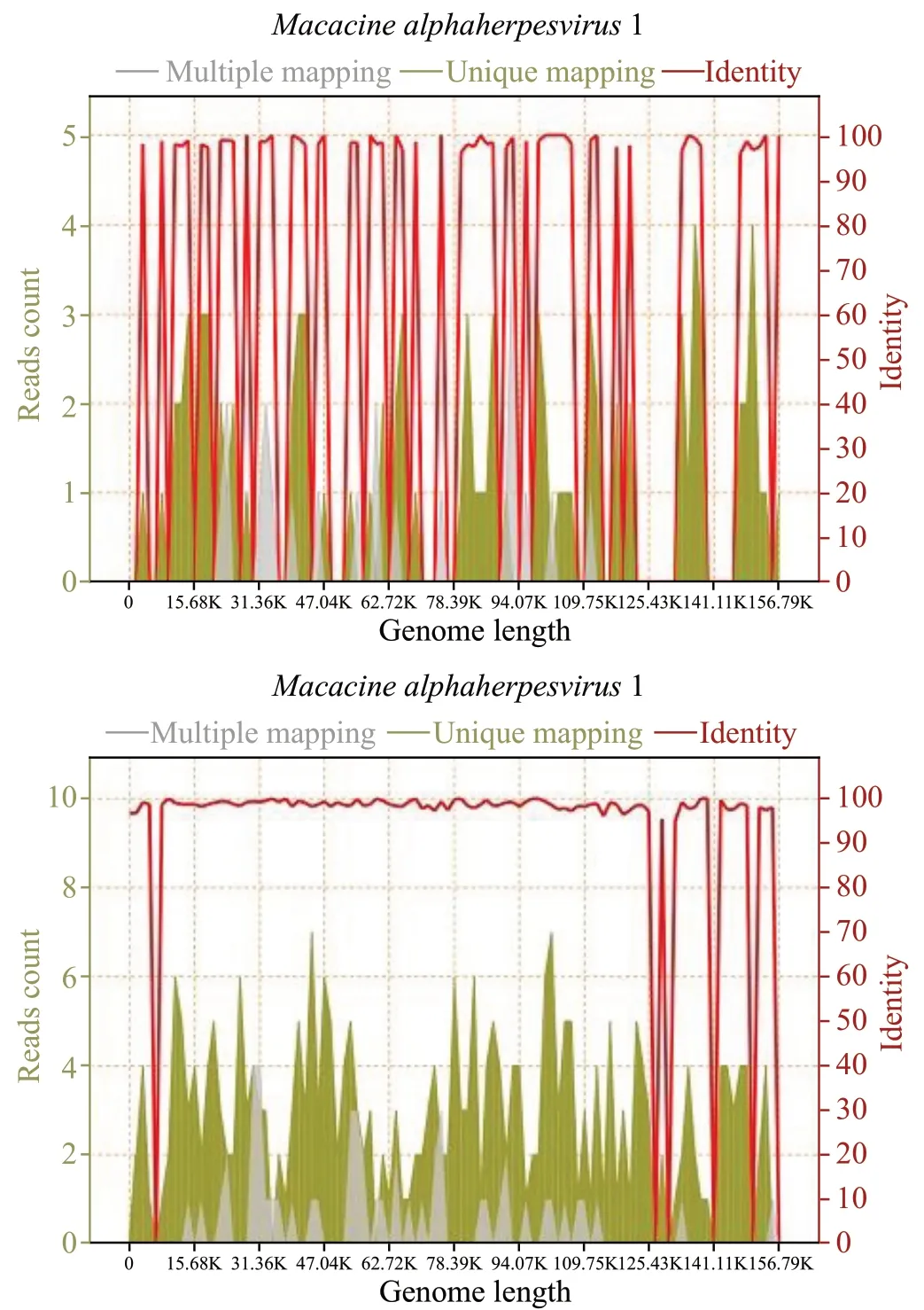

On April 15, two separate clusters of small vesicular lesions emerged on the left and right sides of his anterior chest wall (Figure 1). On April 16, medical history obtained from family members revealed that the patient had necropsied two M. mulatta (rhesus) who had died suddenly with no apparent cause at his workplace on March 4 and 6, 2021. The patient had worn just a surgical mask and nitrile gloves while handling the necropsy. Given the epidemiological context, zoonotic BV infection was highly suspected. On April 17, a lumbar puncture was performed. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was clear and light yellow in color; the CSF pressure was 290 mmHO (1 mmHO=9.8 Pa). Based on the high suspicion index for BV infection, routine and biochemical examination of CSF was not applied. Metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) of his CSF identified a Macacine alphaherpesvirus. RNA and DNA sequencing libraries from CSF yielded 90 and 285 sequence reads, respectively (Figure 2). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays performed at the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed the diagnosis of BV infection. The patient was transferred to the hospital of infectious disease for further treatment on April 19. Although spontaneous respiration eventually recovered, his neurologic status failed to improve, and he died after discontinuation of life support on May 27.

DISCUSSION

Figure 1. Dermatologic feature of B virus in a 53-year-old man. A: a cluster of small vesicular lesions on the left anterior chest wall; B: a cluster of small vesicular lesions on the right anterior chest wall.

Figure 2. A total of 90 RNA readings (above) and 285 DNA readings (below) of B virus in cerebrospinal fluid, with coverage of 4.3275% and 13.6910%, respectively.

Zoonotic BV infection was first reported in 1933.A young physician was bitten on the finger by a rhesus macaque engaged in laboratory research. He developed herpetic lesions on the finger, which then involved the central nervous system; he eventually died of acute ascending encephalomyelitis. Herpesvirus was isolated from several tissues. Although herpesvirus was initially identified as HSV, it was subsequently shown to be distinct from HSV and designated as ‘the B virus’. As with HSV in humans, most primary BV infections in its natural macaque host present a benign course, usually occurring in the oral or genital mucosal epithelium and rarely producing overt clinical signs.Most human BV infections are associated with direct contact with non-human primates (NHP); the infection mode is through exposure to oral, reproductive tract or eye secretions, or central nervous system tissues in the macaque. After the reporting of the first case in humans, a small number of sporadic cases have been reported in successive years. Most human BV infections have been related to bites or scratches from macaques.However, additional modes of exposure have been implicated, including the splashing of macaque urine into the eye,needle stick injury,contamination of cuts with material from primary macaque cells in the laboratory,and during cleaning the skull of rhesus monkey.The patient in this case report had dissected corpses of two rhesus and may have been infected through contact with visceral tissues, splashing of body fluids into the eyes, or through contamination of wound; however, the specific mode of transmission could not be clarified.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first documented case of human BV infection in China. To date, only 28 documented cases of human BV infection have been reported from the US, Canada, or European countries.However, there have been many unconfirmed reports of BV infection in Asia.Several factors may explain why most zoonotic infections with BV have occurred in North America and Europe rather than Asia. Firstly, people often live and work closer to macaques in Asian countries, the natural habitat of M. mulatta (rhesus), which may have led to an adaptation to the BV during the evolutionary process,resulting in lower incidence of BV infection. In addition, arriving at a definitive diagnosis of BV infection in humans is very challenging.Therefore, BV infections in Asia may be missed due to a lack of diagnostic facilities, particularly in rural areas with limited access to healthcare. Furthermore, workers have contact with macaques and medical personnel may overlook the possibility of BV infection. Lastly, in recent decades, many patients with suspected BV infection are likely to have been treated prophylactically with antiviral drugs immediately after a BV exposure incident, leading to a lower detection rate of BV infection.

Due to the advances in biomedical technology in Asia, NHP is widely used for experimental research; however, the modalities for health monitoring and reproduction of pathogen-free macaques groups are far from perfect.The occurrence and development of zoonotic BV infection depend on the intensity of exposure, viral load, and the immune status of the patient. In this case, the patient performed monkey necropsy under basic protection with surgical masks and nitrile gloves, which is perhaps insufficient to prevent BV infection. Every facility in Asia using macaques should comply with a BV infection prevention policy that requires rigorous adherence to institutional standards for the safe handling of macaques. Personnel directly involved in necropsy or handling of samples should wear personal protective equipment (PPE), including coveralls or surgical gown made of Tyvek or similar water (and blood) impermeable material, mask or respirator, face shield, hair covering, double gloves, boot or shoe covers.Immediate first aid during the initial minutes after injury or exposure is crucial to decrease the risk of infection. Wounds must be thoroughly washed and sterilized. Finally, the injured worker must immediately notify the supervisor and seek healthcare. The medical staff needs to be trained in assessing and treating BV-exposed persons tracking NHP-related injuries, exposures, and potential infections. This would enable early preventive measures and treatment and help avoid serious consequences.

In the previous reports, the main cause of sudden death in BV cases was respiratory arrest due to BV infection of the CNS, which can cause severe encephalomyelitis and even brain stem encephalitis.However, our patient developed retrosternal pain during the early stage of the disease. Echocardiography suggested extensive left ventricular wall dyskinesia with transient elevation of myocardial enzymes; electrocardiogram showed a ST-segment depression. All these ECG changes were completely resolved. Since the patient fulfilled the clinical diagnostic criteria for fulminant myocarditis, we highly suspect that the cardiac arrest was attributable to BV infection. To date, there is no documented case of myocarditis caused by BV. Even HSV-induced myocarditis is an uncommon entity.However, physicians need to pay heed to the possibility of myocarditis in cases of BV infection.

CONCLUSIONS

We present the clinical features of the first documented case of fatal BV infection in China. This case report illustrates that human BV infection is no longer a distant threat in China. Therefore, PPE should be strongly recommended in all NHP areas to prevent BV infection as far as possible. mNGS testing for infectious diseases of unknown origin, especially for specimens from sterile body cavities, might facilitate early diagnosis and evaluation of diseases. However, further study is required to determine the reasons for the susceptibility of the patient to BV and the pathogenesis of fulminant myocarditis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention staff members for their work to confirm the diagnosis of BV infection. We also thank Professor Ai-dong Shen, Fei Wang, and Chao Wang for providing precious comments in the grand rounds.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81773931 and 81374004), as well as the Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals Clinical Medicine Development of Special Funding Support “YangFan” Project (ZYLX201802).

Ethic approval: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Friendship Hospital, Capital Medical University. Written consent for publication was obtained from the patient's family.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributors: TPZ and ZZ are co-first authors. TPZ and ZZ have equal contributions to the article. They are all involved in conceptualizing and wring original draft.