Craftinga Saga

Zhang Yan

Fts long history and traditional culture haveendowed China’s capital of Beijing with anabundance of intangible cultural heritage and anensuing vast number of traditional techniques.According to Li Linlin, deputy director of BeijingCultural Heritage Protection Center, the capital’sinheritance boasts three gleaming assets: a longhistory, huge diversity and wide popularityamong the society’s highflyers and grassrootsalike.

In recent years, the center has adopted variousmethods to preserve many different forms ofcultural heritage, one such example being thatfor time-honored brands, it helps organizeinheritor training. Academic and teachingresources in Beijing-based universities make itpossible for these inheritors to take classes there, expanding their minds on brand marketingand upgrading their design philosophy. It alsostrengthens the recording of intangible culturalheritage through various publications starringnational-level heritage representatives.

According to Li, the storage and recordingof these cultural resources is a key part ofprotection efforts. They make full use of digitaltechnology and other modern ways to document inheritors’ knowledge and practices, such as bycollecting existing documents as well as logging oral accounts and shooting instructional videos.

For centuries, craftsmen have been workinghard to preserve these cultural fortunes denoting typical symbols of Chinese civilization and culture, and passing them down to the next generations.

Insistence and Inheritance

The center hosted an event to promote its undertakings on February 3. For the occasion, Han Haijuan from a Beijing-based jewelry studio presented a real-size gold-wire diadem modeled on the one excavated from the Ding Mausoleum of Emperor Wanli (1563-1620) of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), wowing those in attendance. According to Han, its filigree inlaying consists of eight major processing procedures, each bearing its own unique features—all extremely difficult to create.

To Han, welding proves the trickiest among the eight processes: If the degree of heating is not meticulously managed, the whole thing will have to be discarded. “The key to carry on with this job is the spirit of persistence and the passion for this art. Throughout each and every procedure, craftsmen pour their own emotions into the creation, and thus every work bears an inimitable soul,” said Han.

The art of filigree inlay, also called “fine gold art,” combines two craft skills. One is filigree, which includes techniques like nipping, plaiting, jointing, piling, filling, and knitting, and uses gold or silver threads of different weights. The inlaying craft, complicated, graceful and majestic, was limited only to the imperial palace in ancient times. In recent years, as filigree inlaying works often appear in costume dramas, many young people have developed an interest in this art. Today, the Beijing Institute of Fashion Technology and Central Academy of Fine Arts even offer courses in the fine art. The center, too, has dispatched teams to communities and businesses to give lectures on filigree inlaying.

Tangibly Tricky

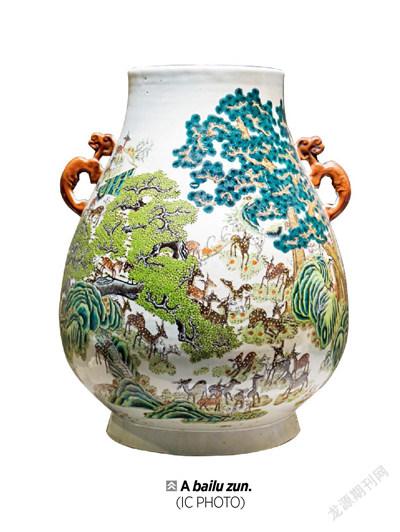

Beijing decorative porcelain, another intangible cultural element, was originally a technique confined within imperial walls, but later made its way to the common people during the late Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). Take the bailuzun, a decorative vessel with 100 deer painted on the porcelain, as an example. Born in the 18th century during the reign of Emperor Qianlong (1736-1796), it was created by no less than 2,000craftsmen, its visuals adjusted and refined more than 300 times overa period of 10 years. Every strandof deer hair on the wine vesselwas painted on by craftsmen, onedetailed stroke after another.

“Decorative porcelain is atypical project of intangiblecultural heritage protection. It requires craftsmen to not onlyinherit the techniques, but spendtime learning about the relevant ancient culture. We are trying our best to present this art tothe public by introducing it on campuses, incommunities and online,” said Yang Xue, a fifth- generation inheritor of the craft. “Sometimes,we invite laymen to come enamel the vessels inperson. This type of Beijing ceramics has alsomade an appearance at international eventslike the Conference on the Dialogue of AsianCivilizations and the Belt and Road Forum forInternational Cooperation. Guests are thus ableto experience what the art of decorative porcelainholds,” Yang continued.

“These knots may look cute, but theyare hard to make,” said Li Wei, a heir of theintangible cultural heritage of knot-making. “Usually, people try to make solid ones, but my target is to make neat, symmetrical and flowing knots. They come in a wide variety, made of cotton, hemp, silk, nylon, and even gold and silver threads. They can be appliedto ornaments, apparels, handbags, furniture, and so on, to make these things appear more attractive.”

Li first developed a strong interest in the art ofknot-making when he was very young, but it wasn’t until he turned his hobby into a profession thatLi began to fully grasp the meaning of the word“craftsmanship.” “It not only requires patiencein the process of making knots, but moreimportantly, perseverance; the handworktakes up a lot of time and you often feel you don’t have enough (time). We must takethe traditional techniques and hand them over to the next generation, all the whileadding some of our own innovations.”

Like many other inheritors, Li Weihopes that more people, particularly the younger generations, will join the effortto protect and pass on intangible culturalheritage. “I hope more people will connect with the big family of knot-crafting, andtheir interest will thrust them into furtherprofessional studies. And we hope that theseartistic knots can become sewn into people’s dailylives.”