NIGHT MOVES

–TRANSLATED BY DYLAN LEVI KING

HU YUESHENG 胡月生

Born in Shaoxing, Zhejiang province, in 1992, Hu Yuesheng works as an urban and rural planner by day. She describes herself as in love with the city, the countryside, and the people who live on this land. Hu writes short stories and draws comics, and has published two short story collections,Goodbye, Jianghu(《再见江湖》) andA Flash Back of How We Got Married(《关于结婚的一场倒叙》), on the digital publishing platform Douban.

“C heck!”The crisp sound of the chess pieces on the board echoed up into the leaves of the poplar tree. There was a tap and a slide, and another soldier fell. The player whose General was in danger straightened his back. He had broken out in a cold sweat. He stared at the pieces on the board, noting their position, studying the peeling lacquer.

He knew that he had lost but he wasn’t willing to resign the game. He was a veteran of these games in the park. In this world, he was a venerable General. When men get up in years, their worlds shrink, as if they are returning to childhood. Children compete for modest prizes like a bouquet of plastic flowers; old men compete for dignity and honor. That’s why he wasn’t willing to resign the game. He held his breath and continued silently studying the board. His ears were turning red from frustration.

“Forget it,” the man across from him said. “It’s just a game.” The man stood up. “We all made promises when we were young. How many fell by the wayside?”

“My word is my bond,” the veteran said. “I never break a promise.”

“Is that right? So you still remember what you promised way back then?”

At those words, the veteran seemed to be waking up from a dream. But by the time he lifted his head, his opponent was gone, and the flock of people that had gathered to watch their game were fluttering away.

He decided to take a stroll through the supermarket. There was one beside the park. He went in and bought a bottle ofshaojiuwine and two packs of salted peanuts. Auntie Liu was working the register. She recognized him. As she scanned the items, she asked him, “Are you expecting company today?” When he shook his head, Auntie Liu glanced up at his face. “Are you drinking alone?”

“That’s right,” he said. “Drinking alone.”Auntie Liu clucked her tongue. “I thought you’d quit,” she said. “What happened? Is your liver alright now?”

“Same as before,” he said. “I don’t think it’s going to get much better.” He pointed at the selection of cigarettes behind her and said, “Get me a pack of the Hongtashan, too.”

She rolled her eyes. “If you’re going to drink, might as well smoke, too, huh?”As he walked out, he gently swung the plastic bag in his hand. He was feeling something that he hadn’t felt in a long time. He couldn’t remember how long ago it had been, whether he was in his late teens or early 20s when he started, but he often used to make the same walk, carrying the same cargo of cigarettes and liquor. His father had been an officer in the military and his family had done alright for themselves, but he went in another direction. He hung out with the young punks in the neighborhood, using whatever cash or ration tickets he could scrounge up to buy cigarettes and liquor. They would smoke themselves stupid and drink themselves blind. After that, there wasn’t much left to do but beat each other bloody. He had grown up in a military compound, so he was used to getting slapped around. When it came to fighting the neighborhood goons, there weren’t many that could best him.

One of his challengers turned out to be a bit unusual. He had come ready to fight, for no apparent reason. The veteran had beaten him up. The challenger had run off. And a few days later, he was back again. The veteran beat him up and the same cycle repeated itself. The challenger was getting better and better. Finally, it happened: The challenger came and fought him to a stalemate. They were both evenly matched. Neither would back down. They kept fighting for more than an hour. In the end, both of them were bleeding. They fell to the ground, too exhausted to move.

The veteran was lying flat on his back. He reached into his jacket pocket and pulled out a cigarette. It’d been crushed to a pulp. He threw it over and it landed on the challenger’s face. He told the challenger that he amused him: Even though he’d been beaten up, he kept coming back, never giving up. He asked him what the point was.

The challenger laughed. He put the cigarette in his lips. That’s where he kept it, never even bothering to light it. He told the veteran that he wanted to find a worthy adversary. He wanted to do more than just trade blows. He wanted to trade his life. The challenger said that most people go through life without much purpose. The only way to live authentically was to take your life into your own hands and stake everything on it.

The veteran felt the same way.

The challenger told him that was why he had kept coming back.

The veteran laughed. “You must be out of your mind,” he said. But he admitted that it was a rare thing—a person who thought this way. There can only be one sun in the sky and one tiger on the mountain. A person like that, the world would only permit one of their kind. The day would come when the winner of their contest was decided. The veteran had laughed, as if he found the whole thing funny, yet he was serious. He reached into his pocket and pulled out the battered, bloody pack of cigarettes. He ripped off a shred and wrote: “Fifteenth. Night. Same place.”

“You wrote it down,” the challenger said, “so don’t forget it.”

The veteran held up the scrap of paper. “My word is my bond,” he said. “I never break a promise.”He wrote it down and he did not forget it, but he was unable to make the appointment. On the night of the 15th, with a full moon rising above them, the Red Guards showed up at his door and dragged away his father. He stood in the doorway for a long time. He felt as if he were standing on a beach as the tide swept in. He looked out into the darkness. The water was rising. By the time he came to his senses, the water was already at his chest. He tried to swim back through the door but it was too late. The red waves crashed down on his head. The sky above was blotted out. There was no way to outrun the waves. That night, he was caught in the flood of history. He tumbled in the waves, cut off from everyone around him.

He put the bottle of liquor down on his old writing desk with a thump. He heard his wife frying something in the kitchen. The hot vegetable oil skittering around the edge of the pan made a sizzling sound. The old familiar smell filled his nostrils.

He went out into the courtyard and watered his flowers. He fell into a trance, waving his hose back and forth over the oleander and azaleas. The flower pot was soon full. The water ran over the rim. He went to feed his canary. He called her name, “Sister Qiao!” She hopped around in her cage as he poured more food into her dish. “Wife,” he called inside, “don’t forget: The flowers have to be watered twice a day, once in the morning and once at night. You need to feed Sister Qiao when her bowl is empty, and wash her cage. She needs her water changed at least once a day.”

The sound of rattling crockery and pans came from the kitchen. “Those are your flowers,” said the old woman, “and that’s your bird. What are you telling me for?”

“Don’t forget,” he said. “And don’t worry about anything else.”

He went back into his house. From the drawer in the writing desk, he took out a tin box. He opened it up and took out a crumpled shred of paper. Time had yellowed it. He looked at what was written on it. He took a slug of theshaojiuand felt it burn in his chest. Tears came to his eyes. He fixed his hair in his reflection in the window. “Where did my coat go?” he called to his wife.

“It’s in the closet. Way in the back. Are you going out?”

“I’ve got something to do tonight,” he said.

“Don’t you want dinner?” his wife asked.

“I’m fine. I’ve got something to do tonight.”

He heard the sound of the pan being dropped into the sink. It echoed like the crash of thunder. “Huh,” his wife grunted, “you could have told me before I went through the trouble of making it. You never change. I should have realized it a long time ago. I must have been blind to have chosen you.”

He took his jacket out of the closet and tucked the pack of Hongtashan into the pocket. “You weren’t blind,” he told his wife. “I always loved you.”

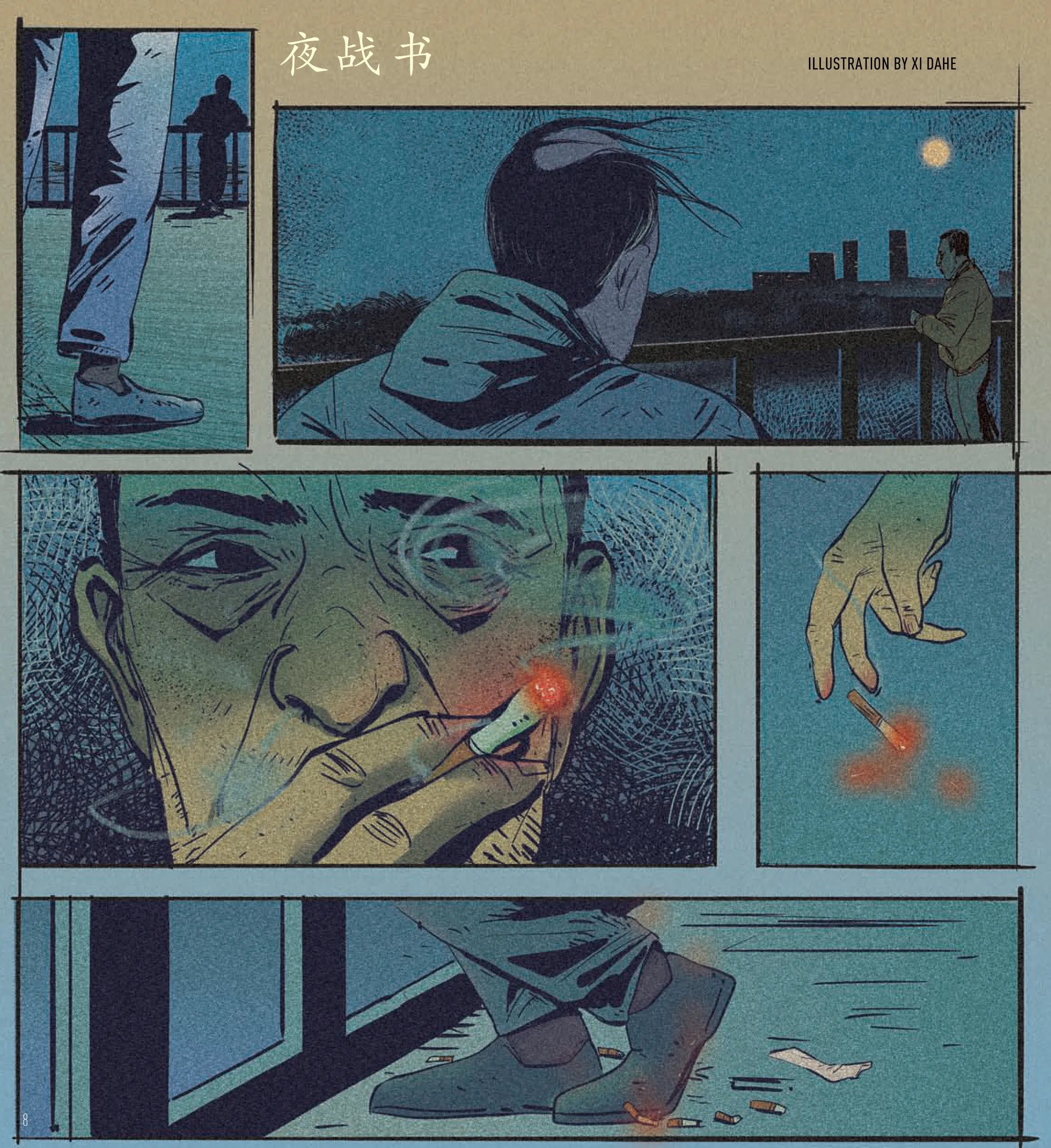

He stood at the edge of the river, feeling the autumn breeze. He lit a cigarette and looked up at the moon. Images flicked across his eyes, as if he were flipping through a photo album. Some of the photographs were familiar and some not. They were yellowed, curling at the edges...

He remembered that there had once been a factory on the other side of the river. It was gone. A park had replaced it. There was a shopping mall beside it. When he was young, there had been a sorghum field there. On the side of the river where the veteran stood, there was no reinforcing bank, no parkland, and no concrete. The ground was covered in gravel. It wasn’t a beautiful place. Back in the day, he remembered, there were not many cars. Having a bike meant that you came from a wealthy family. He used to ride a Phoenix. He remembered riding along this river, a Hongtashan in his lips, feeling the envious gaze of everyone he passed.

Of course, not everyone liked him. He knew there were people that wrote him off as a spoiled brat, the rotten son of a good family. If his father hadn’t been an officer in the military, they said, there’s no way a kid like him would get away with pushing his luck like that. Without a good family behind him, a kid like him could’ve ended up with a bullet in the head. He knew what they said. It pissed him off. He couldn’t prove them wrong but he didn’t want to admit it. He couldn’t ignore it, either. Those words had haunted the veteran—until he met the challenger. The challenger knew what was in his heart. They had lain together beside the river, all bruised and cut, stained red by the setting sun. They had cursed each other. Not a part of their bodies was spared from injury.

The veteran dropped his cigarette and stamped it out. The butt joined many others that had collected there.

He reached into his jacket for the pack. He weighed it in his hand. It was the last cigarette. He pulled his hand back out of the pocket. There were footsteps approaching. They were slow. They were familiar. They didn’t sound like the footsteps of a young man.

“My word is my bond. I never break a promise.”

He brushed off his sleeves and lifted his head. The moon above was full.

MARTIAL TEA

The young man’s eyes bounced back and forth between the placard by the teahouse door and the address scrawled on the scrap of paper he held tightly in his hand. When he was sure they matched, he knocked. When nobody came, he let himself in. His gaze found the red-tasseled spear mounted on the wall.

A voice called from behind the young man: “Who are you looking for?”

He straightened and turned abruptly. “Master Yang!” he said.

An old man with a wispy gray beard stood among the tables. The old man’s eyes were sharp and full of life. His yellow silk robe hung over a wiry frame. There was something profound and dignified in his manner, which could not be concealed.

“Master Yang,” the young man said. “That’s who you are, right?”

The old man confirmed the surname but not the title.

The young man could not contain his excitement. “I spent months looking for you,” he said. “I went up and down these streets, searching every little alley.” Even after someone had told him the teahouse might be the place, it hadn’t been easy to find. In thejianghu—the shadow world of fighters and thieves—Master Yang was called the “Spear King of Changjie.”

When the young man asked if he had the right person, the old man simply said, “You had a rough time of it. Have a cup of tea.”

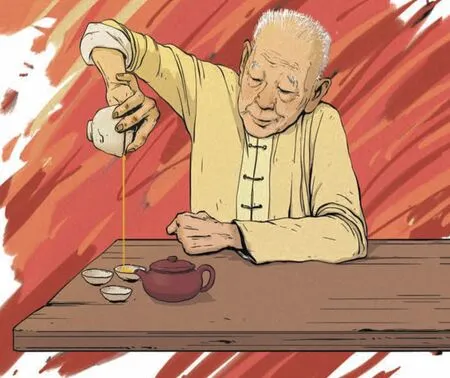

They sat down together. The table was not particularly ornate or extravagant, but the camphor wood’s patina revealed its age. The setting was simple, and in the classical style. On the wooden plank were a row of small glazed white cups, larger porcelain cups, and a clay teapot. A copper kettle was heating on the charcoal brazier in the corner of the table. Droplets of water spat out of the rim of its lid and trickled down the design cast in the side of the kettle, so it looked like it was sweating in the heat.

Master Yang lifted the kettle from the stove, cradling the handle in a rag. He set it on a cushion beside the service.

“The water has to cool down a bit,” Master Yang said. “It should not be boiling. Just eighty to ninety percent of the way there is enough. If it’s too hot, the leaves will not bloom. They won’t give up their flavor.”

The young man had never considered making tea a task that required much skill. It was far more complicated than he had ever imagined.

Master Yang poured water over the tea leaves he had added to one of the larger porcelain cups. He paused when he heard the young man make an almost imperceptible grunt.

“What’s on your mind?” Master Yang asked.

“Master Yang,” the young man said, “I mean...I wanted to know, in thejianghu, fighting your way up against all these masters, each with their own special skill—I mean, that must be really cool, huh?”

Master Yang ignored him. He put a lid over the porcelain cup and strained the water through it, dumping it on the floor.

The young man thought he had offended Master Yang. “What are you doing?” he asked.

“I’m washing the tea,” Master Yang said.

“Why would you need to wash tea?” the young man asked.

“As they grow, the tea leaves are buffeted by the wind and rain,” Master Yang said. “They gather the dust of the world around them. It has to be washed away.”

The young man nodded, silently cursing himself for revealing his ignorance.

Master Yang poured more water into the cup, put the lid on again and let it steep. After a while, the old man picked up the larger cup, tilted it slightly, and sent tea gently cascading through the strainer and into the small vessel. It caught the sunlight as it fell, glowing like a ribbon of gold. The motions of the old man’s wrinkled hands and thin wrists were steady and sure. The cup was held absolutely still in his hand, without the slightest tremor.

“Your wrists must be so strong,” the young man said with a sigh. “How long do you have to practice to be able to do that?”

“All you have to do is drink tea,” Master Yang said, “three times a day, for about fifty years. After that, anyone could master it.”

“Right, right, right,” the young man said.

The young man leaned forward with his elbows balanced on his knees. His shoulders dropped. After a moment, he caught himself and sat upright. He still struggled to contain his excitement. He felt sweat trickling down his back. He was surer than ever that the Master had otherworldly abilities. But it all kept coming back to tea. The young man tried to put it together. He decided that must be how people of this level of cultivation talked. Master Yang was concealing his power. He appeared to be making idle conversation, but there was deep meaning. There were mysteries concealed in these simple remarks. The young man had heard that true masters knew how to restrain themselves, never revealing their abilities until absolutely necessary. Even once the fight begins, a true master holds back. They retreat. They fall back and let you advance, analyzing your movements. They size up the situation with complete clarity. The true master might appear to be shaken, but, when they finally strike, they will put you to shame.

The young man tried to calm his racing thoughts and focus. If Master Yang chose tea as the metaphor for his teachings, then the young man knew he must concentrate on the process.

While the young man tried to figure out all of these things, Master Yang had finished preparing the tea. He pushed a small cup toward the young man. “Please,” Master Yang said, gesturing at the cup.

The young man did not want to risk hesitation. He picked up the cup. He held it up to inspect it. The liquid in the cup was a faint crimson and gave off a delicate aroma. He took a sip. The flavor was subtle but impressive.

“How is it?” Master Yang asked.

“It’s pretty good,” the young man said. “To be honest, I don’t know much about tea. This is black tea, right?”

He took another sip of the tea and lowered his head, ashamed of having exposed his ignorance again.

Master Yang poured water over the tea again. He poured a second cup for the young man. “Try it again,” he said.

The second brew was golden red. The young man took a sip. The flavor had mellowed, the young man thought, but he worried that he couldn’t taste much of a difference beyond that. He raised the cup again and stole a glance at Master Yang over the rim. The old man was absorbed in his tea. He tilted his head back and slurped noisily. The tea squirted into his mouth, like a bubbling spring.

The young man came to a realization: The reason that he couldn’t detect any difference in the second brew was because he was trying too hard to find the difference. There was a lesson being taught in the tea tasting, the young man thought to himself. The immature mind loves to make comparisons where none should be made. But that causes you to lose your focus and become incapable of achieving anything.

“Amazing,” the young man said. “I finally get it.”

Master Yang cast a skeptical look at him. He was not sure what the young man was getting at. He picked up the porcelain cup and prepared the third brew.

The young man gathered his thoughts and raised the cup to examine the color. This brew was darker. It gave off almost no aroma. He took a sip. The taste of the tea leaves overwhelmed all other flavors in the cup. He put down the cup with a sigh of satisfaction. He looked up at Master Yang. “It’s much more bitter,” he said.

On the third brew, the flavor of the tea leaves themselves was more pronounced, but it was accompanied by much more bitterness. It is like the experience of human life, the young man thought to himself. The process symbolizes a man who has accomplished a few things entering middle age. The first two brews represented the younger years. The young man couldn’t help but think of himself, wandering in ignorance, asking after this master and that school, worried about finding the correct path. But drinking the tea, he had realized that he was still young enough that he had no need to worry. Youth was a time of infinite possibilities.

By the time he picked up the cup filled with tea from the fourth brew, the young man felt as if he had mastered the tasting process. He examined the color of the tea, tasted it on his tongue, swallowed, then savored the aftertaste.

The bitterness was gone. The delicate aroma of the first brew returned. The flavor of the tea leaves was just right. The young man drank two cups. It was like a spring breeze. Returning to his metaphor of the course of a lifetime, he imagined an old man walking out of the mountains after a decade in seclusion. The unassuming old man was dressed in rough clothes, but striding confidently back into the world, a spear held in front of him. Back among the hustle and bustle of human society, the man slowly raised his eyes to take it all in. His pupils were crystal beads that converge beams of light. His gaze penetrated through the heat of battle and through all emotion, staring directly at the banner of the most powerful fighter under heaven.

The fifth brew of tea was rust red. The flavor had faded. The man that had walked out of the mountain was standing in the ring; the battle ended, the onlookers stunned, his skills proved. With one hand, the man held up his banner, and with the other, he held a young maiden. His spear was strapped across his back. From that moment forward, he descended into the underworld and became a notorious wanderer, accompanied only by his weapon. His suit of armor and his skin seemed to be fused together. He traveled on clear nights on a path lit by the moon. He had bested all of his competition. He was in a state of martial perfection. If anybody saw his long shadow as dusk approached, they might mistake him for a god. Word would spread. One story would become ten, multiplying over time, until he became another legend of thejianghu.

The name would echo down through the years—the Spear King of Changjie!

But on the sixth brew, the Spear King of Changjie put down his weapon. He took shelter in his dim quarters, keeping to himself. He had the air of someone retreating from pain. People came and went from his door, but he never rose to greet them. It was hard to say whether he was mourning the departure of someone close to him—or perhaps waiting for someone’s arrival. But as long as he waited, nobody came. He remained in the shadows. He made sure that his face stayed hidden, just like the flavor of the tea, like the bud clipped from the branch, like the frost spreading across the ground, like the soul slipping from the body.

The young man was overcome with a wave of nausea. He had to put down his cup. Master Yang looked up. “What’s wrong?” he asked.

The young man shook his head. “I’ve had enough,” he said.

Master Yang studied him, then raised the kettle again. Without speaking, he began pouring water into the cup.

“Master Yang,” the young man said, “how many times can you brew this tea?”

“First gradeyancha? Seven times.”

“The last brew just tastes like water, right?” the young man asked.

Master Yang took the young man’s cup. He poured in the tea and pushed it back toward him. “Try it,” he said.

The young man looked down at the cup. The tea was a pale yellow, as if it had been colored by a single drop of blood. His mind cleared. He leaned in close to the cup, trying to smell the faint aroma. The young man wasn’t sure whether what was in his cup should be called tea or teaflavored water. He put the cup to his lips and felt the heat of the porcelain rim. He took a gentle slurp.

The warm liquid slipped into the young man’s stomach. Warmth spread throughout his body. He felt as if he had swallowed a seed that was germinating inside of him. A flower bloomed. Branches grew. The delicate fragrance of green leaves clung to the inside of his nostrils. A tea tree grew inside of him. The young man opened his eyes. He saw the spear, set against the blank white of the wall. The tassel seemed alive with flame. The iron tip gleamed like silver.

The Spear King of Changjie stood in front of his weapon, his back turned to the table. In his yellow silk robe, he looked every inch the legend that the young man imagined.

The Spear King asked the young man why he had come in search of him. The young man answered that he was looking for a master. He said that he wanted to learn martial arts. The Spear King asked him why. The young man said that it was because he liked hearing about the legends of thejianghu.

The young man said that he wanted to go into thejianghu. He wanted to earn a living by his blade, fighting his way through the underworld. He wanted to learn to fight, to destroy evil and promote good, to save the dying and help the sick. He wanted to roam free with the woman he loved. He wanted to understand the mysteries of the human realm. He wanted to achieve enlightenment. He said all of this. He couldn’t hold back any longer. The young man collapsed to the ground, bowing to the Spear King, and knocking his forehead against the floor. He begged the Spear King to accept him as a disciple and teach him what he knew.

Master Yang studied him for a moment and then told him to get off the ground.

“So you promise?” the young man asked.

“Promise what?” Master Yang asked.

“Promise to take me as a disciple,” the young man said.

“When did I say that?”

The young man crawled to the feet of Master Yang. “If you don’t want me as a disciple,” he said, “why did you drink tea with me? Why did you teach me that stuff?”

Master Yang went to the window, pulled up the bamboo blind, and looked outside. The sky was clear. The streets of the small town were unchanged. Not too far away, two girls were leaning against a bus stop, looking down at their phones. One was playing a game and the other watching a TV show. Further down the street, two boys were harassing a blind beggar. One of the boys picked up the beggar’s stainless-steel bowl and slapped it down over his head.

Out in the world, everyone was busy with their own affairs. A man rushed by, talking on the phone about his wedding reception: how many tables they needed, how many guests to invite...After that, the topic turned to condo prices and school districts. It devolved into an argument. The man turned red in the face. He went into a restaurant. In the doorway, a man and a woman were saying goodbye to each other. The woman was his boss. As they talked, the man seemed to subconsciously bow his head to her. What were they talking about? Work, probably, or promotions. A bus rumbled past them, full of people just getting off work. They stood, pressed in together. A few of them were looking around, glancing at the world passing by outside, but most were absorbed in their phones. The wheels on the bus kept rolling, rolling, from one station to the next.

Master Yang lowered the blind. He shook his hand, dismissing the young man.

“What is all this aboutjianghuand Spear King? What era are you living in? Do you see anything like that out there? I asked you to drink tea because I wanted someone to drink tea with. I just want to pass the time.”

He laughed.

Author’s Note:These stories are inspired by a conversation I had with my friend, a devoted lover ofwuxiastories. He was very disappointed at the decline of contemporarywuxialiterature, and claimed that the romance of the martial underworld is forever gone. But I believe that the spirit of the swordsmen never dies. I think such a sentiment is built-in among people with a Chinese cultural background. Even when it is shrouded in the mist of history, hidden in the concrete jungle, or submerged in everyday life, there will always be people missing the swordsmen who were free to love and hate; and there will always be people who continue the legend of thejianghuin their own ways.