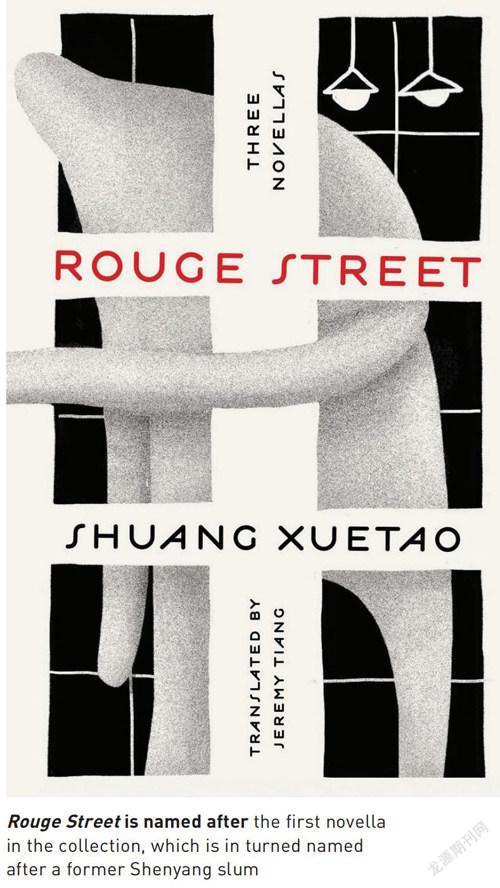

The Rouge Street Blues

A new translation from one of China’s brightest millennial writers breathes life into Dongbei, China’s post-industrial rust belt

《艳粉街》英文版面世,看青年代表作家双雪涛和后工业时代的东北

It sometimes feels as if literary fiction in translation from Chinese lags behind its source material by several decades. Among novels translated from Chinese last year, few writers under the age of 60 were represented. The writers that grew up in the 1960s and 1970s, like Yan Geling, Yan Lianke, Jia Pingwa, and Can Xue, are still producing excellent work—but the vitality of modern mainland literature comes from the writers inspired by them.

That is why Jeremy Tiang’s rendering of Shuang Xuetao’s is one of the most important translations of modern Chinese literature to come out in the past several years. It’s a rare chance for those overseas to read a younger author, still ascendant.

Born in 1983, Shuang is part of a generation of young writers that rarely makes it into English translation, at least at book-length. Despite beginning his writing career in 2011, Shuang has only had two short stories translated into English prior to this project, in online journals Pathlight and Asymptote. But he has been well celebrated among Chinese literary circles for years, most recently winning the Blancpain-Imaginist prize in 2020, a prestigious award for China’s finest young writers.

Shuang has emerged as one of the voices of a new wave of northeastern Chinese writers, a group that also includes Ban Yu and Zheng Zhi, whom Tiang is also currently working with. Neither of the other two has found his way into translation offline yet. Apart from the fact that they are criminally under-translated, these writers share an ability to combine bone-hard realism, dark humor, and narrative playfulness.

As a debut collection of short fiction by a single young writer, is something rare in Chinese literature in translation, which tends to focus on novels. Blame the internet, blame online publishing platforms like Douban, blame the continued vitality of Chinese literary journals—but the best young Chinese writers, unlike their older peers, are less likely to produce novels, rarely stretching beyond what could be called a (中篇小說, “mid-length novel” or novella). In this collection, Tiang has picked three novellas from different collections of Shuang’s short stories, each of them united by a shared setting. Accompanying them is a foreword by Madeleine Thien, providing context for the stories and their setting.

A talented writer being creatively curated is no guarantee, however, that it won’t turn into sludge in translation. Modern literary fiction from China tends to be rendered by academics for an academic audience. It is good to see that Shuang’s book has been assigned to Tiang, a legitimately gifted writer who approaches translation as creative work rather than a mechanical process. Tiang shows in the same creativity and mastery that he brought to his renderings of other mainland literary fiction, including Yan Ge’s and Li Er’s .

The three stories in the collection revolve around a shared setting, the titular , or Yanfen Jie (艷粉街), a residential district in Shenyang, Liaoning province, formerly populated by workers in the manufacturing sector. Thien’s foreword gives specific context for this part of Shenyang and its factories, namely that it was settled by “alleged class enemies and their equally despised children, former felons, hooligans, peasants, migrant workers, and the poor.”

It’s a setting not typically found in modern Chinese works that make it into translation, but within China, the Northeast—or Dongbei, the provinces of Liaoning, Jilin, and Heilongjiang—occupies an interesting place in the cultural landscape in the post-reform era. It’s a cold and sparsely populated region only settled by Han Chinese in significant numbers starting from the last century of the Qing dynasty (1616 – 1911), and later became the industrial heartland of the PRC, with millions of workers resettled in the region and employed in its factories, forges, and mines.

When the planned economy receded, factories and mills began to be sold off by the state, and laid-off workers either stayed in the post-industrial slums to watch their state benefits run dry, or ran to find work in the manufacturing centers along the southern coast. One of the narrators of “Bright Hall,”, the second story in this collection, remembers it as a time when the world seemed to fall apart: “The factory seemed to collapse all at once, but actually there’d been warning signs for some time...My father continued showing up for work at the usual time, but sometimes he didn’t change into a clean uniform at the end of the day, because there’d been nothing for him to do, and he hadn’t sweated.”

Shuang grew up in the aftermath of that time, when the Northeast came to represent backwardness, poverty, and the vices that came with it: violent crime, boozing, and drug abuse. Young people got out, if they could, while the elderly were left behind. The Northeast became known for cultural exports such as comedians with funny accents, doomed folk singers, dreary documentaries, and gritty crime thrillers. It’s worthwhile to connect to the global canon of de-industrialization art and literature, records of what happens when industries that sustain communities are shut down—to compare the forces that shaped Dongbei’s cities to the same forces that shaped Flint, Magnitogorsk, Youngstown, Scunthorpe, Detroit, Dunaújváros, and Hamilton.

These are places upon which a great deal of unhappiness has been visited. It’s no mystery why the novellas collected in are shot through with a persistent hopelessness. We can understand why failure, death, and hunger are omnipresent.

T

he most hopeful and straightforward of the novellas—“The Aeronaut”—begins the collection. It provides rapid immersion into a world of factory workshops and housing developments, bitter cold, and hard drinking.

“The Aeronaut” contains one of many sketches of life in the wake of de-industrialization. The narrator’s mother stands in for the community itself: “Ma used to be a very warmhearted person. According to my father, she had been a ray of sunshine in her youth...After the factory went bankrupt and the two of them had to fend for themselves, her spirits grew a little heavier. When their home was demolished in the government’s urban clearances, and they had to move to a shanty town on the outskirts of the city, her spirits grew heavier still.”

Shuang loves his narrative games and hyper-realistic trickery, but he can still write prose that reeks of charcoal, piss-soaked corridors, and onion breath: “They were given a new apartment in compensation, but it never got any sunlight, no one ever cleaned the shared corridors, and the young renters upstairs were professional thugs.” In “The Aeronaut,” we get a taste of the generational disconnection that haunts all de-industrialization literature. The grandparents’ generation grew up with absolute hope, having seen their lives transformed in the Maoist glory days. Their children have either found their own form of freedom or sunk into ruin in the aftermath of factory closures, while their grandchildren are left to sort out what little has been left as an inheritance.

At the center of the collection is “Bright Hall.” Shuang’s stories often resist easy summaries, but in a nutshell, it’s a story of how two motherless sons collide. Zhang Mo is sent by his alcoholic father to stay with his aunt at a rundown church that hosts a charismatic ex-convict preacher; in a parallel narrative, Liu Ding is a tough kid being raised by his grandmother, who makes friends with the school janitor (also an ex-convict, formerly locked up with the preacher) and begs the latter to carry out a hit for him. The realist plotline takes a knee-jerk turn toward fantasy in its final pages, the two boys ending up under a frozen lake in a horrific interrogation.

“Moses on the Plain” closes the collection. This is the novella that helped launch Shuang to literary stardom when it appeared in the preeminent literary journal Harvest in 2015. The story starts out as a romance in 1990s Shenyang between two youths working at a cigarette factory, then shifts abruptly to a cop turning up a grisly spree of murders in the midst of a nationwide crime wave, and cascades into a polyphonic account of multigenerational urban decay and social disorder from the Cultural Revolution to the millennium. The narrative games feel novel, even though Shuang shows his work by dropping references throughout the novella to the authors he’s cribbing from (Turgenev, Murakami, and Faulkner, among others).

is an experiment for its publisher. It is a rare treat to be able to read a young Chinese author at length in translation, especially one that eschews the novel form. The decision to group novellas from multiple sources by loose theme and setting for the English translation was inspired. Tiang’s writing is perfectly calibrated to Shuang’s shades of gray.

It’s an experiment worth repeating.

Dylan Levi King is currently translating Ban Yu’s short story collection Winter Swim for publication into English.

When it comes to gender-based expectations, Chinese TV audiences are increasingly flexible: quasi-homoerotic “Danmei” TV shows and foreign series with sympathetic female rebel characters are watched by billions. But at the same time, producers and screenwriters rely on conservative templates: TV stations have been discouraged from platforming “sissy” men, while the ideal Chinese heroine seems to be one who becomes a good mother or wife. Here, Professor Geng Song of the University of Hong Kong tries to plug an important research gap: Drawing on extensive interviews with Chinese audiences from a wide variety of backgrounds, examines how nationality and gender roles in mainstream Chinese TV have been constructed—and how they in turn construct Chinese people.

It begins with a fatal alarm call. After telling his lover to wake him early during a bout of evening drinking, illiterate village gangster Hongyang is found dead the next morning. The rest of the novel is a rural whodunnit, a masterclass in suspense that pieces together how Hongyang connived and punched his way through the criminal underworld to the top of his small town in Jiangxi province. This was A Yi’s debut novel back in 2017, before he went on to have a star-studded literary career. It drew heavily from his own experiences as a policeman in a similar town as the novel’s setting.

Today Zou Jingzhi is a celebrated screenwriter, but once upon a time he was just another dust-caked farmer on the North China Plain. Originally published 12 years ago, Zou’s memoir of growing up in Beijing during the Cultural Revolution and then being sent down to the countryside is a tender look back and a pensive reflection on a time that many others remember for its violence and tragedy, but which for Zou was dominated by the banal and the boring. It’s an ordinary coming of age—the toys played with, the friends made, the lessons learned. History makes only the occasional grim cameo, reminding the reader that dramatic events are usually just the sideshow on life’s main stage. – Alex Colville