Clinical classification of symptomatic heterotopic pancreas of the stomach and duodenum: A case series and systematic literature review

Michael T LeCompte, Brandon Mason, Keenan ] Robbins, Motoyo Yano, Deyali Chatterjee, Ryan C Fields,Steven M Strasberg, William G Hawkins

Abstract

Key Words: Heterotopic pancreas; Ectopic pancreas; Aberrant pancreas; Pancreatic rest; Groove pancreatitis

INTRODUCTION

Heterotopic pancreas (HP) is an uncommon embryologic abnormality, defined as aberrant pancreatic tissue separated anatomically from the main body and blood supply of the pancreas. This tissue can be located throughout the gastrointestinal tract with a reported frequency of 1 /500 in surgical specimens[1 ]. Most of these lesions are asymptomatic and are identified incidentally on pathologic specimens or at autopsy. However, some of these anatomic anomalies can manifest clinical symptoms. When this occurs, the clinical presentation can often be severe, requiring surgical intervention[2 ].

Knowledge of the clinical features of this disease process and the appropriate treatment is limited.While reports of clinically relevant cases are present in the literature dating back to 1727 , the majority of the available literature consists of case reports, with few studies containing more than a handful of patients[3 ]. Thus, little is known about the “typical” clinical manifestations of HP due to small volume studies. Classification of this aberrancy is further limited by the diversity of possible symptoms which are often dictated by the anatomic location, size and functionality of ectopic lesion. While HP is most commonly located in the foregut, it has been identified in tissues including the small bowel, colon,gallbladder, spleen, esophagus and mediastinum[4 ]. This leads to further complexity in appropriate diagnosis and treatment of HP as it is often mimics other disease processes.

To address the deficit in description and classification of symptomatic HP we evaluated our center’s experience with symptomatic HP cases and compared it to a systematic review of the available literature. The scope of this study focuses on describing and characterizing the common clinical manifestations for HP within the stomach and duodenum as these locations represent the majority of cases. Cases identified in this study were compared with the results of a review of the available reported cases to identify the common symptoms, presentation, and treatment options for this disease process.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A review of pathology specimens from 2000 -2018 was conducted at a single academic institution.Approval was obtained from the institutional review board (#210811062 ). Specimens with pathologic confirmation of heterotopic pancreatic tissue were identified. Lesions found in the upper gastrointestinal tract were selected in adult patients over 18 for final review. Electronic medical records were analyzed and factors associated with the clinical presentation, symptoms, diagnosis and treatment were identified in each of the cases. Based upon the clinical history and presentation, patients were classified as symptomatic or asymptomatic. Symptomatic patients were defined as those who presented with upper gastrointestinal complaints which could be attributed to the identified pathology and ultimately resolved with treatment or removal of the ectopic tissue. Asymptomatic patients were classified as patients in whom the presence of heterotopic pancreas was identified in the workup or treatment of symptoms related to other clinically established pathology, or were found incidentally in a surgical pathologic specimen. Symptomatic patients were analyzed and categorized based upon their clinical features, presentation and treatment.

The cohort of patients with symptomatic manifestations from our institution was then compared that of published cases in the literature. A literature review of heterotopic pancreas using Embase and PubMED databases was conducted. The terms “heterotopic pancreas”, “ectopic pancreas”, and“aberrant pancreas” were searched. Publications printed in the English language were selected.Inclusion criteria were limited to publications reporting symptomatic cases of pathologically confirmed heterotopic pancreas located in stomach or duodenum. Publications which reported symptomatic and asymptomatic cases were excluded if they lacked characterization and description of clinical symptoms.Patients from the included publications were combined into a single cohort and categorized based on the presenting clinical symptoms, available demographic information and treatment. This sample was then compared with a series of patients identified at our institution for similarities. Descriptive statistics were employed to tabulate and report the results.

RESULTS

Institutional results

Twenty-nine pathology specimens were identified with pancreatic heterotopia in the upper gastrointestinal tract during the study period of January 2000 to December 2018 . Of these, fourteen patients were female (48 %). Six patients (20 %) were identified as having symptoms related to an HP lesion. The remaining patients were identified as asymptomatic with incidentally noted lesions on pathology or discovered on endoscopy (Table 1 ). Five of the symptomatic patients underwent surgical treatment of their disease process and one declined surgery in favor of medical management.

Of the symptomatic patients, two (7 %) presented with elevated lipase and evidence of pancreatitis within the heterotopic lesion, two patients presented with gastrointestinal bleeding or anemia, one patient (3 .4 %) presented with perforated gastric ulceration related to a heterotopic lesion, and one patient presented with gastric outlet obstruction from a HP lesion located at the pylorus. The six case presentations are briefly summarized below.

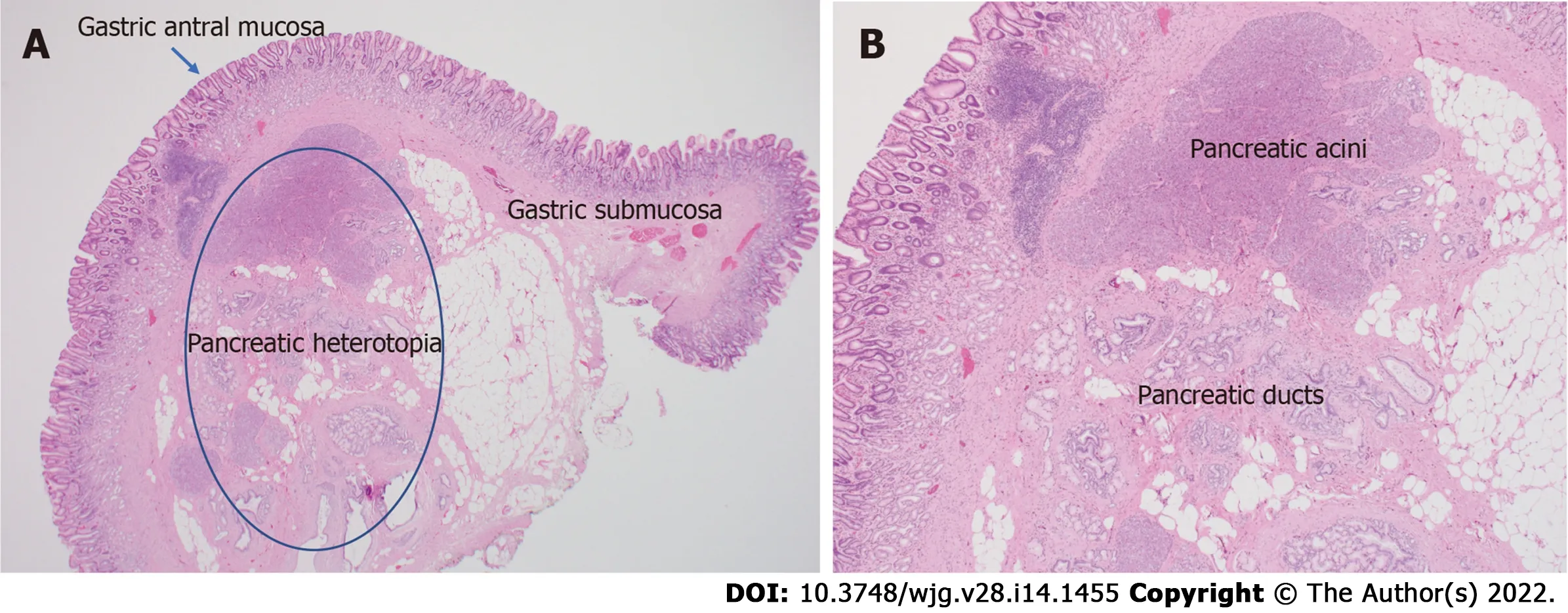

Case 1: 28 -year-old male who presented as an outpatient with a history of mid-epigastric abdominal pain, nausea and daily vomiting for approximately 3 mo. He reported associated anorexia and a weight loss of approximately 40 Lbs. On exam he was noted to be cachectic with a BMI of 17 with moderate abdominal tenderness to palpation in the upper abdomen. Workup demonstrated an elevated lipase of 123 and an amylase of 141 . Computed tomography revealed a 3 .4 cm hyper-enhancing mass near the pylorus on CT imaging. This was associated with a complex fluid collection within the wall of the stomach and evidence of inflammatory stranding, gastric thickening and edema. Endoscopy revealed a mass within the wall of the gastric antrum. Endoscopic ultrasound and biopsy demonstrated pancreatic acini. The patient was subsequently taken to the operating room for antrectomy and billroth IIreconstruction. His pathology demonstrated heterotopic pancreatic tissue, 3 .5 cm in size within the gastric antrum (Figure 1 ). In addition, there was an associated 4 .3 cm pseudocyst within the gastric wall with surrounding inflammation. The patient was seen in follow up clinic one month later and was noted to be eating well with an increase in his weight of 14 Lbs since discharge.

Table 1 Pathologic specimens identified with heterotopic pancreas; specimens are divided into symptomatic classification

Case 2: 37 -year-old male who presented with a chief complaint of melena, epigastric abdominal pain,anorexia and weight loss of approximately 20 Lbs. An esophagogastroduodenoscopy was performed which demonstrated a 2 cm submucosal mass with overlying ulcerated mucosa. An endoscopic ultrasound and FNA were obtained. Results demonstrated atypical cells. Radiographic imaging was obtained, however computed tomography scan was unable to identify or localize the mass. Surgical resection was offered, and the patient underwent a laparoscopic assisted gastric wedge resection.Pathology from the specimen was identified as a 2 .5 cm × 2 .0 cm mass consistent with multilobulated pancreatic tissue located between the gastric mucosa and muscularis propria with evidence of inflammation and ulcerated mucosa. The patient recovered without complication and with resolution of his anemia.

Case 3: 42 -year-old male presented with acute abdominal pain and the presence of free air on upright abdominal film. He was noted to be tachycardic and with evidence of peritonitis on exam. A computed tomography scan confirmed the presence of free air and intraperitoneal fluid in the abdomen. His past medical history was notable only for a history of gastroesophageal reflux and indigestion that was refractory to years of proton pump inhibitor therapy. He was taken to the operating room for exploration where a large ulcer was identified upon opening the lesser sac in the posterior wall of the stomach approximately 6 cm from the pylorus. A distal gastrectomy and reconstruction with a billroth II gastrojejunostomy was performed.

Pathology from the resected specimen demonstrated a transmural gastric perforation with evidence of associated pancreatic tissue within the gastric wall and along the edge of the ulcerated mucosa. The patient tolerated the procedure well and remained symptom free.

Case 4: 43 -year-old male presented to the emergency department with chronic symptoms of nonbloody, non-billious vomiting and intolerance of oral intake. A detailed history revealed that the patient had suffered from intermittent vomiting and progressive oral intolerance over the prior 6 mo. A computed tomography scan was obtained which demonstrated a grossly distended stomach and a hyperenhancing mass as the level of the pylorus and first portion of the duodenum with an associated gastric outlet obstruction.

He was taken to surgery where an abnormal mass was palpated near the level of the pylorus. A distal gastrectomy was performed with a billroth II reconstruction. Final pathology demonstrated heterotopic pancreas at the level of the pylorus.

Case 5: 52 -year-old female presented with anemia underwent upper endoscopy, which showed a submucosal mass along the lesser curve of the stomach near the incisura. EUS was performed, where a submucosal mas was identified with ulceration concerning for a gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Fine needle aspiration was non-diagnostic. She proceeded to surgery where a laparoscopic wedge resection was performed. Her pathology showed a 1 .5 cm × 1 .1 cm × 1 .0 cm mass of pancreatic tissue. On postoperative follow up she was noted to have resolution of her anemia.

Case 6: 29 -year-old male presented with abdominal pain and anorexia over the course of on year with a weight loss of 75 Lbs. Imaging with computed tomography showed 2 .6 cm × 1 .6 cm mass along the lesser curve of stomach and the patient was noted to have mild elevation in his amylase and lipase.Upper endoscopy with endoscopic ultrasound demonstrated a 2 .3 cm subepithelial lesion along the lesser curve with surrounding gastritis. Biopsy demonstrated chronic gastritis and benign pancreatic tissue. The patient was placed on proton pump inhibitors and carafate with improvement in his symptoms. He was referred for surgical evaluation but declined intervention as his symptoms had improved with medical therapy.

Results of literature analysis

A systematic review of the literature was conducted to identify published cases of HP lesions. The initial search resulted in 1220 unique publications. Of these, 232 publications described cases of symptomatic lesions and met the inclusion criteria. The majority of these publications (n= 182 ) were single patient case studies. There were only 20 studies identified which contained more than 10 symptomatic patients in their series. The majority of the larger studies contained cases of both symptomatic and asymptomatic disease with few publications dedicated to describing symptomatic cases. In total, these studies included 1762 patients of which 934 patients were reported to have symptomatic lesions in the stomach or duodenum and comprised the total cohort of this evaluation. Demographic information was provided for 864 patients (94 %) of which the mean age at symptom presentation was 43 years old and 564 were male (61 %). In total, there were 556 patients with gastric lesions (59 %) and 378 with duodenal lesions (41 %).

A summary of the clinical cases of HP was performed by individual publication and were tabulated for review in Table 2 . The majority of patients presented with epigastric abdominal pain (n = 620 , 67 %).In addition to pain, the remaining symptoms were noted to fall within one of 4 predominant diagnostic categories: (1 ) Dyspepsia, which included symptoms of epigastric pain, eructation, nausea or bloating with meals (n= 445 , 48 %); (2 ) Pancreatitis within the ectopic lesion (n = 260 , 28 %); (3 ) Gastrointestinal bleeding (n= 80 , 9 %); and (4 ) Gastric outlet obstruction (n = 80 , 9 %). There were also 37 patients who presented with jaundice and biliary obstruction due to periampullary lesions (4 %), and 3 patients with perforated ulcers. The remaining patients presented with various symptoms which included fever,diarrhea, abscess, carcinoid syndrome and dysphagia but were in single cases or small numbers. The majority of patients who presented with pancreatitis were found to have radiographic evidence of pseudocyst formation or cystic degeneration of an ectopic lesion (n= 251 , 97 %). These lesions were commonly located within the wall of the stomach or duodenum or were characterized as “groove pancreatitis” with ectopic pancreatic tissue located between the medial duodenal wall and the head of the pancreas. Of the patients with clinical and radiographic evidence of pancreatitis, only 50 cases (19 %)reported elevations in biochemical markers such as serum amylase or lipase to correlate with the clinical or radiographic evidence of pancreatitis. One hundred forty-five cases (56 %) were reported to be associated with alcohol consumption as the inciting etiology.

The majority of cases (n= 832 , 90 %) underwent surgical or endoscopic management of their heterotopic pancreatic lesion, while 92 were observed or managed medically. Surgical therapy ranged from radical gastrectomy or pancreaticoduodenectomy to local excision or endoscopic resection.Available data on the therapies provided are listed in Table 3 . Data on the effect of treatment on symptom control was available for 645 patients. Of the cases which reported post-intervention follow up, five hundred forty-nine patients demonstrated symptom resolution with treatment (85 %), 63 were reported to have symptom improvement (9 .7 %) and 33 reported no improvement (5 .1 %). Based on the level of detail reported in the literature, there was no delineation of whether patients who did not improve were treated medically or via surgical or endoscopic intervention. Likewise, there was no study providing a direct comparison of treatment outcomes between medical versus surgical therapies nor was there a study comparing outcomes between different interventional therapies.

321182181122212131112261011121121214765172182573111154623295111271672673117523327352121425943532512411361228112366562343312549 .242 .45540 .53441464347 .540414144506 .8514345 .2607283349 .811123277221061021496136267343293012321272341761023237934964212432920062006200620052003200220022000199919961993198819881986198419811980197719741973197319711966 Ormarsson et al[4 ]Pessaux et al[2 7 ]Ayantunde et al[2 8 ]Chatelain et al[2 9 ]Zinkiewicz et al[3 0 ]Shi et al[31 ]Huang et al[32 ]Otani et al[33 ]Hsia et al[34 ]Fekete et al[35 ]Flejou et al[36 ]Claudon et al[3 7 ]Pang et al[38 ]Lai et al[39 ]Mollitt et al[40 ]Armstrong et al[4 1 ]Thoeni et al[42 ]Yamagiwa et al[4 3 ]Dolan et al[44 ]Eklof et al[45 ]Nebel et al[46 ]McGarity et al[4 7 ]Abrahams et al[4 8 ]

1237571883313518038260122421804219311664453316310966207442375637820215101265564444 .643 .134 .84339 .14343285171829784351541182176119621961195819461947 Tonkin et al[49 ]Dirks et al[50 ]Martinez et al[5 1 ]Waugh et al[52 ]DeCastro Barboso et al[1 ]Singlecase studies(n =182 )[3 ,53 -233 ]Total

DISCUSSION

Heterotopic pancreas is a congenital anomaly, often identified incidentally in asymptomatic patients,yet it has the ability to illicit significant clinical symptoms in some cases. These lesions can arise in tissues throughout the body including stomach, small bowel, gallbladder, esophagus and mediastinum,leading to a wide range of manifestations[234 ]. Characterization of symptomatic lesions is difficult due to the relative infrequency of this diagnosis and the variability in presentation. This often leads to misidentification and suboptimal management in many cases. Large volume studies characterizing the common presentation of HP are lacking and the aim of this study was to provide a conglomerate population to classify the typical clinical presentation within the foregut and aid in classification. With improved understanding and recognition of this disease process, clinicians can render more appropriate treatment decisions that may save patients morbidity from radical resection.

The clinical manifestations of HP are dictated in large part by two factors, the location and the functionality of the lesion. The anatomic location is often predetermined early in life by embryologic development. The exact mechanism by which this abnormality forms is not well understood however, it is believed to be related to a disruption in the normal embryologic migration of the pancreas. Formation of dorsal and ventral pancreatic buds results from endodermal outpouchings of the duodenum[235 ].Aberrant separation of these tissues from the visceral endoderm may be responsible for retained pancreatic tissue within the developing gastrointestinal tract and subsequent migration as the embryo develops[235 ]. However, this theory does not fully account for the development of HP in all cases as this anomaly has also been reported to be found in tissues outside the gastrointestinal tract including the gallbladder, fallopian tube, umbilicus, mediastinum, omentum, mesentery and spleen[9 ,39 ]. An alternative explanation in these cases is the “metaplasia” theory in which totipotent endodermal tissues develop into pancreatic tissue during embryologic development and can present in various tissues throughout the body[235 ].

Table 3 Treatment of heterotopic pancreas; listing of surgical or endoscopic procedures performed for patients with symptomatic heterotopic pancreas by procedure

However, the majority of these lesions are located within the upper gastrointestinal tract with surgical and autopsy data reporting a frequency within the stomach of 25 -52 %, 27 -36 % in the duodenum and 15 %-17 % in the jejunum[9 ,44 ,235 ]. HP symptoms often mimic common upper gastrointestinal pathology and are difficult to identify. The location within the foregut often dictates symptom manifestation with peripyloric lesions more likely to lead to gastric outlet obstruction while periampullary lesions may cause biliary obstruction[17 ,80 ,164 ,236 ,237 ].

In addition to the anatomic location, the histologic location within the layers of the visceral wall may also have an effect on symptom presentation. HP occurs most frequently between the submucosa and lamina propria but can be found within all layers of the visceral wall[238 ]. Submucosal lesions may be more likely to cause ulceration with local gastritis or duodenitis while transmural lesions which involve all layers of the bowel wall can lead to chronic inflammation, and ultimately stricture or perforation[77 ].

While location may often explain symptom presentation it does not fully account for why some lesions are symptomatic while others found in similar locations are not. The remaining factor can be potentially explained by the functionality of the lesion, and the ability to perform the normal exocrine and endocrine functions of the pancreas. Histopathologic evaluation by Heinrich in 1909 demonstrated differences in the composition of these lesions which were later revised by Fuentes in 1973 [239 ,240 ].These classification systems categorized HP lesions based on the presence of all the cellular components of functional pancreas tissue (Type I in both categories) versus presence of ducts, acinar tissue or islet cells alone (Fuentes classification types II, III and IV respectively)[240 ] (Figure 2 ). The presence or absence of histologic elements may affect the functionality of the lesion and contribute to its ability (or inability) to produce symptoms. It has been proposed that lesions with functional exocrine potential can produce local chemical irritation of surrounding tissues while those without appropriate ductal drainage may lead to pancreatitis and pseudocyst formation within the lesion[4 ,60 ].

The clinical nature of HP may therefore have variable patterns of presentation which are highly dependent on both the location and the functional ability of the lesion. Since the majority of identified cases are located within the upper gastrointestinal tract, the scope of this study was restricted to identifying and characterizing symptoms within these locations. The combined experience from our center and the analysis of the published literature demonstrated that the majority of clinically significant cases can be categorized within 4 main groups. These categories are significant as they are common presentations of other pathology within the upper GI tract and can lead to difficulty in diagnosing and treating this pathology.

Figure 2 Histopathologic images. A: Histologic appearance of heterotopic pancreas in the stomach; B: High power view of heterotopic pancreas demonstrating pancreatic acinar and ductal architecture.

Dyspepsia

The majority of cases identified in this series reported symptoms consistent with epigastric abdominal pain, bloating, belching and nausea which are typically associated with eating. This category consisted predominantly of patients with gastric lesions. The manifestation of symptoms has been thought to be related to local chemical irritation of the gastric mucosa by products of the exocrine pancreas[87 ]. This acts as an inciting factor that then may lead to inflammatory mucositis and subsequent gastritis or duodenitis, with or without ulceration. As many of these patients present with identical symptoms to those with peptic ulcer disease (PUD) (and indeed, are often misdiagnosed as such), many authors argue that ulceration is the inciting factor and etiology of the majority of symptoms associated with HP[2 ,44 ]. In the series of 34 patients reported by Armstrong et al[41 ] the extent of mucosal involvement on pathology was correlated with symptoms suggesting a causal relationship. In the series published by Laiet al[39 ] comparing the histology of symptomatic and asymptomatic patients, 49 % of symptomatic patients had mucosal ulcers while asymptomatic patients in their series lacked objective evidence of ulceration or gastritis.

Mucosal ulceration in some cases may progress to visceral perforation. This is thought to be the result of normal evolution of inflammation seen in peptic ulcer disease, with ulceration of the protective mucosal barrier, caused by heterotopic pancreas, acting as the initial catalyst. Perforation may also be related the degree of penetration within the gastric wall of the ectopic lesion. Extension of the HP lesions through the serosa can be seen in up to 4 % of histologically examined specimens[84 ]. Lesions which penetrate deeper through the layers of the gastric wall can lead to transmural inflammation,necrosis and perforation of the stomach wall. This theory is supported by the histologic findings reported by Martinezet al[51 ] demonstrating inflammation and fibrosis extending through multiple layers of the gastric wall on tissue histology depending on the histologic depth of the lesion. Overall,this is a rare complication of HP, with only three identified publications describing visceral perforation related to HP[77 ,121 ,241 ]. We report the fourth known case above in Case 3 where the transmural gastric ulceration was clearly associated with HP. It is possible that additional cases exist but remain undocumented as they may have been treated with omental patching without resection or biopsy. Still,this remains an uncommon symptomatic presentation of HP compared to local mucosal ulceration.

While there are clear associations for mucosal ulceration with the symptomatic presentations of HP it does not account for all cases. Multiple series including that of Dolanet al[44 ] report on patients with symptoms of dyspepsia who did not exhibit evidence of ulceration or gastritis. This is also supported by reports such as that by Ormarssonet al[4 ] and Barbosa et al[242 ] which demonstrate resolution of symptoms in patients undergoing resection of HP with and without the presence of ulceration. In these patients, the etiology of abdominal pain and/or dyspepsia is not fully clear. It has been proposed that exocrine secretions into the stomach may affect the pH composition of the gastric lumen leading to alterations in the digestive process, gas formation and bloating, although confirmation of thisviatesting of gastric pH in the setting of HP has not been conducted to our knowledge[47 ]. In addition, it is hard to conceive that these lesions, unless the reach a large size, are able to secrete enough volume to significantly alter the pH composition of gastric juices.

The majority of patients with HP and dyspeptic symptoms are initially misdiagnosed and managed with medical therapy designed for reduction of acid secretion. It is unclear whether traditional treatments for gastritis and PUD is beneficial in these patients. If the inciting physiology is chemical irritation from pancreatic secretions, then traditionally prescribed therapies to reduce acid secretion would be unlikely to help alleviate symptoms. In patients who develop mucosal ulceration there may be some plausible benefit that acid reduction may prevent ulcer progression once breakdown of the mucosal barrier has already occurred. However, it is not clear whether this can promote adequate ulcer resolution in the setting of HP or prevent future recurrent ulceration since acid secretion is not believed to be the causative factor for inflammation or ulceration in this setting[41 ]. There were few symptomatic patients in the reviewed studies who were managed with observation or medical therapy and long term follow up was lacking. The single patient treated with medical therapy at our institution (Case 6 ),demonstrated symptomatic improvement and to date, has not returned with recurrent symptoms over six years of observation. However, an adequate evaluation of medical management compared to surgical or endoscopic resection is lacking and further study is needed to evaluate the optimal treatment modality.

Heterotopic pancreatitis

Manifestations of acute and chronic pancreatitis in HP tissues were the second most common presentation in our review. Clinical symptoms may include abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, anorexia and weight loss[85 ,163 ]. Similar to orthotopic pancreatitis, the most common causes can be related to alcohol, medications, smoking, autoimmune disease or inadequate ductal drainage[243 ]. According to the histologic classification system proposed by Heinrich and Fuentes, heterotopic pancreas types I-III contain functional pancreatic acini and ductal components. Impaired drainage and outflow obstruction of these ducts may lead to pancreatitis and pseudocyst formation[241 ]. Cystic formation within the visceral wall of the stomach or duodenum was demonstrated radiographically in the majority of patients with pancreatitis in our series. This was often associated with radiographic signs of stranding,edema and inflammation. This pathophysiology is commonly seen in “groove pancreatitis” where ectopic pancreatic tissue between the duodenal wall and pancreas lack appropriate enteric drainage leading to inflamation and cystic degeneration[244 ,245 ].

Diagnosis of heterotopic pancreatitis is made through a combination of clinical presentation,radiographic imaging and biochemical evaluation[243 ,245 ]. Serum labs may yield mild elevations of amylase and lipase however, these levels are usually only modestly elevated, even in the setting of severe inflammation due to the relatively small volume of pancreatic tissue within the heterotopic lesion[235 ]. Leakage of enzyme-rich pancreatic fluid can cause pancreatic pseudocyst formation within the gastric wall producing symptoms of early satiety and gastric outlet obstruction[60 ]. This finding results in the appearance of a cystic structure within the wall of the stomach or bowel and is often mistaken for a duplication cyst or mucinous neoplasm[208 ].

Conservative treatment may be successful in mild cases of this disease process. Investigation of the inciting etiology should be performed with cessation of alcohol or smoking when applicable. However,in patients with repeated episodes of abdominal pain, oral intolerance and vomiting (as in Case 1 above), surgical intervention may be required. When accurately diagnosed, drainage of the pseudocyst and local excision is typically adequate. However, in patients with recurrent groove pancreatitis or cystic degeneration of the duodenal wall, more radical surgical intervention is often required. Groove pancreatitis may require pancreaticoduodenectomy in order to resolve recurrent flairs of pancreatitis and avoid complications such as duodenal stricturing and necrosis of the pancreatic head. The largest series of patients with groove pancreatitis and cystic degeneration of the duodenal wall was published by Rebourset al[25 ] and included 105 patients. In this series, 18 % resolved with observation, 43 %resolved with medical therapy, of which half of these required nutritional support and 39 % required surgical intervention. The majority of patients underwent a pancreaticoduodenectomy (N=`17 ) with the remainder undergoing endoscopic cyst fenestration, biliary bypass or gastric bypass for symptom management[25 ].

Gastrointestinal bleeding

Gastrointestinal bleeding is a rare but potentially serious presentation of HP. Bleeding may manifest as chronic melena as in the two patients in our series (Case 2 and 5 ). However, there are also reports of massive gastrointestinal hemorrhage associated with large volume transfusion and hemodynamic instability[86 ,191 ]. Martinez et al[51 ] reported a rate of bleeding of 7 % in gastric lesions which was supported by the experience of Panget al[38 ] who also reported a bleeding rate of 7 % in symptomatic patients. The largest series of HP published by Dolanet al[44 ] from the Mayo Clinic evaluated 212 cases of HP of which 40 were discovered due to clinical symptoms. Of these, 7 patients (17 .5 %), presented with anemia and or evidence of gastrointestinal bleeding. Overall, the rate of patients presenting with gastrointestinal bleeding in pooled analysis of the literature was 9 %.

The etiology of bleeding in patients with heterotopic pancreas is believed to be related to ulceration of the gastric mucosa overlying the aberrant lesion. As described previously, chemical irritation and inflammation can lead to disruption of the mucosal barrier while pancreatic enzymes, such as elastase,may cause thinning and erosion into the walls of underlying vasculature. Ulceration as the source of gastrointestinal bleeding is supported by the series put forth by Pang and colleagues which reported ulcerated mucosa in pathologic specimens from patients with evidence of bleeding[38 ,86 ]. However,this does not account for all reported cases of bleeding related to HP as there are several cases of documented bleeding and anemia in which the mucosa overlying the resected lesion was found to be intact[246 ]. One proposed explanation for this is through the concept of hemorrhagic “suffusion”. This idea, originally proposed by Madinaveita and Loma, and later described by Hudock and colleagues speculates that chronic inflammation from heterotopic lesions leads to edema and congestion in the gastric submucosa[191 ,247 ]. Congestion of the fragile vasculature in the submucosa may lead to bleeding and diapedesis into the gastric lumen.

Definitive management of major bleeding caused by heterotopic pancreatic lesions is primarily through resection. There is no clear role for medical management in gastric bleeding related to HP. Even among those patients with bleeding related to gastric ulceration, traditional medical management for gastric ulceration is of questionable utility as the presumed etiology of mucosal ulceration is not related to acid secretion. However, there may be an argument that medical therapy may reduce the potential of gastric secretions to propagate ulceration in the setting of an already disrupted mucosal barrier from HP. In the setting of acute gastrointestinal bleeding, endoscopic therapies can be utilized to control hemorrhage but ultimately, resection of the offending lesion should be considered. There have been reports of endoscopic submucosal dissection and resection of HP in patients with melena and chronic anemia[14 ,18 ]. However, surgical resection remains the preferred management of a bleeding mass in most cases. This may be achieved with localized partial gastrectomy or duodenectomy in the setting of small lesions and more extensive resection and reconstructions can often be avoided.

Gastric outlet obstruction

Gastric outlet obstruction is the source of symptomatic presentation in 9 % of patients based on our review. The most common location for lesions arising in the stomach is the distal antrum, accounting for 85 -96 % of cases[94 ]. Given the proximity to the pylorus, growth of these lesions may lead to obstruction of the pyloric channel. While complete gastric outlet obstruction is possible, the more common scenario is partial or intermittent obstruction from a ball-valve occlusion or protrusion of the mass into the pylorus[51 ]. Symptoms associated with this process include abdominal pain, nausea, intermittent vomiting, bloating and anorexia[81 ,162 ]. Gastric outlet obstruction is a common presentation in infants and pediatric patients where smaller lesions can easily occlude the pyloric channel[32 ,247 ].Nevertheless, obstruction is also seen in adults where ectopic lesions grow to a size that can lead to mechanical obstruction as seen in Case 4 [41 ]. Lesions that are small and otherwise asymptomatic for decades, may also become acutely symptomatic in setting of inflammation and edema[60 ,92 ]. Likewise,the development of cysts and fluid collections within the wall of the stomach may grow to a size that can impede gastric emptying[163 ]. Some have also proposed that HP lesions may cause functional obstruction due to pyloric spasm[28 ].

Definitive management involves gastric decompression with a nasogastric tube and surgical correction of the obstruction. Surgical resection in these scenarios will typically require a more extensive resection than local excision or wedge resection as lesions causing obstruction are typically large (> 2 cm) and located at or near the pylorus or duodenum. Distal gastrectomy with a Billroth I, Billroth II or Roux-en-Y reconstruction are the most common operations performed for gastric lesions causing obstruction while partial duodenectomy or pancreaticoduodenectomy may be required in the obstructing lesion in the duodenum. If the lesion is small with a large cystic component causing obstruction and the pathology of the lesion is definitively known prior to surgery, a less extensive resection can be accomplished with preservation of the pylorus[95 ]. In the case series published by Ayantundeet al[28 ], two out of three cases of gastric outlet obstruction underwent distal gastrectomy while one underwent an anterior gastrotomy and local resection of the submucosal lesion. The majority of studies reviewed in the literature however, reported more extensive surgical resection and reconstruction procedures[14 ,58 ,64 ,244 ].

Evaluation and treatment

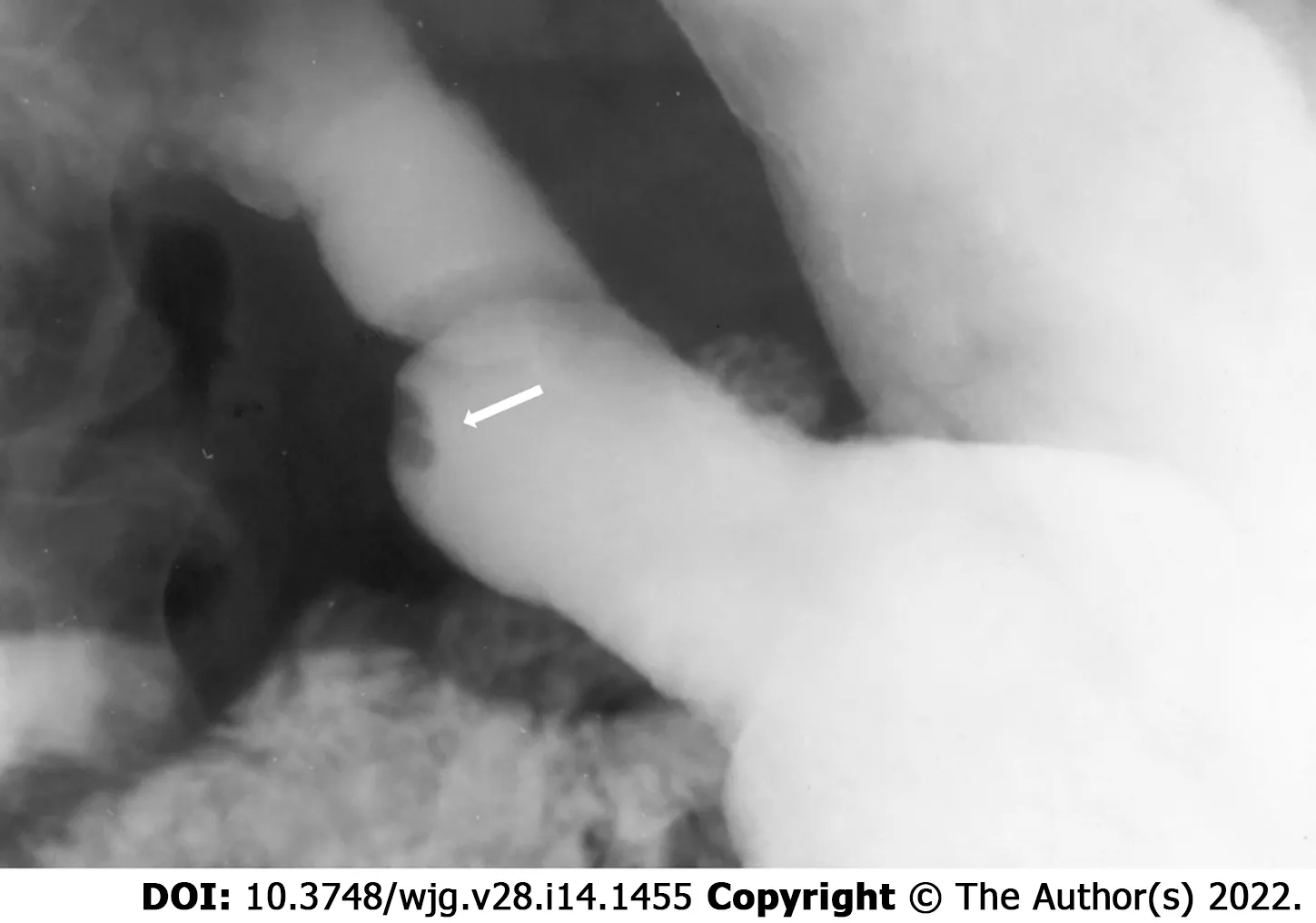

Regardless of the presenting symptoms, accurate diagnosis of HP can alter management and affect surgical decision making. Appropriate imaging and diagnostic studies must be ordered and evaluated carefully if suspicion for HP is high. Lesions of sufficient size can be identified with computed tomography, MRI, and fluoroscopy. When found within the stomach, HP tissue is typically seen along the greater curvature within 6 cm of the pylorus[238 ]. On CT, uncomplicated HP tissue will present as a soft tissue mass within the wall of the stomach, exhibiting similar enhancement and attenuation characteristics to that of normal pancreatic tissue[17 ] (Figure 3 ). However, the attenuation can be variable depending upon the dominant cellular type in the HP tissue, as there are pathologically different structures of heterotopic tissue described and characterized Heinrich's classification system[95 ,248 ]. Due to the variable enhancement of the HP tissue, it can sometimes be difficult to differentiate it from a gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) or other common submucosal lesions[163 ]. In the setting of elevated pancreatic enzymes, sequelae of acute inflammation can be identified surrounding the ectopic tissue (Figure 4 ). On MRI the imaging of HP tissue will follow the signal intensity and enhancement characteristics of the native pancreas on all sequences. The HP tissue will demonstrate high signal intensity similar to that of the native pancreas on non-contrast T1 weighted imaging and demonstrate avid enhancement on post contrast images[234 ] (Figure 5 ). Barium fluoroscopy may also demonstrate a characteristic rounded filling defect with central indentation[241 ] (Figure 6 ).

Figure 3 Coronal (A), axial (B), and (C) sagittal images of the abdomen and pelvis following the administration of IV contrast demonstrates enhancing heterotopic pancreatic tissue within the wall of the stomach along the lesser curvature (white arrows). The heterotopic pancreatic tissue is intramural in location and demonstrates similar attenuation characteristics of the adjacent pancreatic tissue seen on the coronal and sagittal images (white arrowhead).

Figure 4 Computed tomography images. A: Axial image demonstrating heterotopic pancreatic tissue within the stomach (white arrow). B: Axial image demonstrating heterotopic pancreas (white arrow) with associated psudocyst (white arrowhead). C: Coronal reformatted image demonstrating heterotopic pancreas tissue (white arrow) with associated pseudocyst (arrowhead) causing gastric outlet obstruction.

Figure 5 Non-contrast axial T1 weighted (A), coronal T2 weighted (B), and coronal postcontrast T1 weighted (C) images show a lesion within the first portion of the duodenum (white arrow) demonstrating T1 pre-contrast hyperintense signal similar to that of the adjacent pancreas (white arrowhead). This tissue shows similar imaging characteristics of the adjacent pancreatic tissue on the T2 coronal and T1 coronal post contrast images.

Further diagnostic workup may require biochemical evaluation of serum amylase, lipase or, in some cases, tumor markers and/or endoscopic investigation[249 ]. EGD will typically demonstrate the presence of a submucosal mass which may be associated with a central umbilication and or ulceration.At centers with expertise in endoscopic ultrasound, this modality may be helpful in determining the size, location and depth of penetration within the visceral wall. Final determination is achieved by tissue biopsy. This can often be difficult in the setting of ulceration, cystic degeneration and in lesions that are located within the outer wall of the viscera and EUS will may help facilitate accurate targeting and biopsy.

Figure 6 Single spot image of the stomach on a barium fluoroscopic study demonstrates an intraluminal filling defect within the stomach with a central indentation (arrow) consistent with pancreatic heterotopia.

Accurate identification of HP in the diagnostic workup is an important factor in determining appropriate management. Unfortunately, many patients are misdiagnosed or assumed to have alternative pathology at the time of surgery. The range of clinical and radiographic findings makes proper pre-operative identification difficult, especially in the context of a relatively rare anatomic anomaly. Most lesions are mistakenly identified as malignant or premalignant pathology. This often affects the surgical decision making and may lead to a more extensive resection than would otherwise be required. This is evident in studies such as the one performed by Zhanget al[9 ] which reported that over 54 % of patients with HP were misdiagnosed preoperatively. Many of the lesions were presumed to represent malignancy and underwent extensive resections. In our series, 18 patients underwent subtotal gastrectomy, 78 underwent distal gastrectomy and reconstruction and 168 underwent a pancreaticoduodenectomy. As the majority of HP lesions are benign and do not involve the entire visceral wall, many are amenable to local or endoscopic resection. Overall, we identified 158 cases of local endoscopic resection in our series. The largest series was published by Zhouet al[6 ] who reported endoscopic submucosal dissection in 78 symptomatic patients with good results. In this series, the majority of patients had lesions located in the submucosa or lamina propria and were less than 1 cm in size. Likewise, the series published by Zhonget al[14 ] included 30 patients of which 90 % were under 2 cm in size. Thus, an endoscopic approach is a reasonable intervention in pathologically confirmed HP,< 2 cm in size in the submucosa.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, the relatively rare presentation of the disease process makes it difficult to identify a sufficiently large patient population to analyze and draw conclusions from. For this reason, we combined our single institution experience with that of a cohort derived from a literature review in order to evaluate a meaningful number of symptomatic cases. This type of analysis can be subject to inconsistency due to the differences in reporting, and classification of symptomatic cases in the literature. Likewise, a cohort derived from retrospective review of the literature may lead to selection bias as only those cases which are clearly symptomatic or associated with a higher level of severity are reported, potentially neglecting less symptomatic or milder cases. However, given the paucity of data and characterization of this abnormality, the reporting of the known literature and experience of HP in a conglomerate population may be important in the understanding and management of patients and to help guide future analysis and treatment decisions.

CONCLUSION

Heterotopic pancreatic tissue is a relatively rare anatomic anomaly that is found within the stomach and gastrointestinal tract. While numerous case reports of this pathology exist within the literature, there are few large volume studies that describe and characterize the clinical significance of this disease process.Review of a single institutional series and the available literature identified four categories of symptomatic features that occur within the upper gastrointestinal system. Many of these lesions are misdiagnosed and undergo invasive surgical resection. Better understanding of the clinical presentation and diagnosis of these lesions may lead to improved treatment and reduction of unnecessary surgical resection.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:LeCompte M designed the study and performed the research, reviewed the manuscripts and wrote the paper; Mason B and Yano M reviewed the radiographic images and contributed content to the manuscript regarding radiographic identification; Chatterjee D collected and reviewed pathologic specimens; Robbins K assisted in reviewing medical records and collecting data; Hawkins G, Strasberg S, and Fields R participated in designing the study and contributed to the analysis and editing of the manuscript.

Institutional review board statement:This study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of Washington University of St. Louis. IRB number [#210811062 ].

Informed consent statement:Based on the study protocol and design, informed consent was determined to not be required and was therefore not obtained for this study. Patient information was collected and reviewed based on the parameters laid out by the IRB at our institution and was deidentified for analysis and reporting. The remainder of the study population was constructed based on a cohort of patients obtained through systematic review of the literature and was therefore based on patient information which had already been published and presented in the literature. For further questions or concerns please feel free to contact the corresponding author.

Conflict-of-interest statement:The authors of this study have no related conflicts of interest to disclose.

Data sharing statement:Technical data and information were provided by the corresponding author, Michael LeCompte who can be reached at michael_lecompte@med.unc.edu. Data from research subjects was anonymized and excluded any patient identifiers. Given the retrospective nature of this study, informed consent was deemed not necessary by the IRB. Additional data was collected and reviewed from datasets collected and published in the literature.

STROBE statement:The authors have read and revised the manuscript based on the STROBE guidelines.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4 .0 ) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4 .0 /

Country/Territory of origin:United States

ORCID number:Michael T LeCompte 0000 -0001 -8853 -2957 ; Brandon Mason 0000 -0003 -2102 -1233 ; Keenan J Robbins 0000 -0001 -6950 -175 X; Motoyo Yano 0000 -002 -4837 -1906 ; Deyali Chatterjee 0000 -002 -3322 -1163 ; Ryan C Fields 0000 -0001 -6176 -8943 ; Steven M Strasberg 0000 -0003 -0777 -2698 ; William G Hawkins 0000 -0001 -7087 -3585 .

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies:American Hepatopancreatobiliary Association; Society of Ameican Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons; and American College of Surgeons.

S-Editor:Gong ZM

L-Editor:A

P-Editor:Gong ZM

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年14期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年14期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Hepatocellular adenoma: Where are we now?

- Radiomics signature: A potential biomarker for β-arrestin1 phosphorylation prediction in hepatocellular carcinoma

- Comments on “Effect of type 2 diabetes mellitus in the prognosis of acute-on-chronic liver failure patients in China”

- Endoluminal vacuum-assisted therapy to treat rectal anastomotic leakage: A critical analysis

- Osteosarcopenia in autoimmune cholestatic liver diseases: Causes, management, and challenges

- Syngeneic implantation of mouse hepatic progenitor cell-derived three-dimensional liver tissue with dense collagen fibrils