Clinical outcomes of endoscopic papillectomy of ampullary adenoma: A multi-center study

Seong Ji Choi, Hong Sik Lee, Jiyeong Kim, Jung Wan Choe, Jae Min Lee, Jong Jin Hyun, Jai Hoon Yoon, HyoJung Kim, Jae Seon Kim, Ho Soon Choi

Abstract

Key Words: Endoscopic papillectomy; Ampullary adenoma; Clinical outcome; Recurrence; Adverse event

INTRODUCTION

Ampullary adenomas (AAs) are rare lesions, with a prevalence of 0 .04 %-0 .12 % in autopsy, and account for 0 .2 %-5 % of newly diagnosed intestinal neoplasms[1 -3 ]. As the number of endoscopic surveillance or computed tomography (CT) scans has increased, the number of AAs detected has also increased.Patients with AA are often asymptomatic, and other complaints are related to biliary or pancreatic obstruction, such as jaundice, biliary colic, or pancreatitis. Even in asymptomatic patients, an AA needs to be removed because of its malignant potential[4 ]. Furthermore, complete excision of AAs is necessary because of poor diagnostic accuracy with false-negative rates of up to 30 % and diagnostic discrepancy of pathologic results, reported as 25 %-60 %, with forceps biopsy[5 ,6 ].

Endoscopic papillectomy (EP) was first introduced for the treatment of AA by Suzukiet al[7 ] in 1983 ,and both endoscopic and surgical approaches have been considered for the treatment of AA. EP is now considered as the first treatment of choice for benign AA due to the high recurrence, mortality, and morbidity of surgery[8 -11 ]. Nevertheless, there remain concerns regarding EP. The reported EP adverse event rate is over 20 % and while most cases are not severe, this cannot be neglected[12 ]. The recurrence rate after EP is high at 58 .3 %, and re-recurrence or persistence of AA has often been reported, requiring patients to undergo additional procedures or surgery[13 ,14 ]. Despite recent guidelines, there is no consensus on outcome parameters, and there are no established indication for EP or guidelines for EP technique, and no guidelines for the management of recurrence and re-recurrence[12 ,15 ,16 ].

Here, we aimed to evaluate the clinical outcomes of patients who underwent EP and investigate the factors that affect recurrence and adverse events to assist in improving the outcomes of EP and establishing the guidelines for EP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

We retrospectively reviewed the medical charts of patients who underwent EP for AA between January 2013 and December 2019 and their follow-up data until December 2020 at five tertiary hospitals: Korea University Anam Hospital, Korea University Guro Hospital, Korea University Ansan Hospital,Hanyang University Seoul Hospital, and Hanyang University Guri Hospital. We excluded patients who underwent EP or surgical ampullectomy prior to enrollment and those who were followed up for less than a year after EP. Patients with non-adenomatous lesions were also excluded.

Patient baseline characteristics including age, sex, body mass index, clinical presentations, and initial pathologic reports of the lesion were recorded. Patients were screened for familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), and mean follow-up periods were calculated. Parameters for EP techniques were recorded using written reports of EP, endoscopic images, and fluoroscopic images. These parameters included endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), cholangiogram, pancreatogram, submucosal lifting, type of resection(en-bloc/piecemeal), thermal ablation after resection, complete endoscopic resection, bile duct stent insertion (BDS), and pancreatic duct stent insertion (PDS).

EP procedure

EP was performed at five tertiary hospitals with over 500 endoscopic retrograde cholangiography(ERCP) annual cases by seven experts with over five years of ERCP experience. Before EP, EUS was performed at the endoscopist’s discretion. After adequate sedation, the ampulla of Vater was carefully inspected for its size, extent, and signs of malignancy (Figure 1 A). Following the inspection, a cholangiogram and pancreatogram were obtained in cases requiring evaluation of a possible intraductal invasion. Then, snare polypectomy was performed (Figure 1 B). Mucosal lifting using saline was performed if needed. With a standard polypectomy snare, the adenoma was tightly grasped, and the electrical current was applied until complete resection of the lesion was achieved.

En-blocresection of AA was first attempted, and a piecemeal resection was performed ifen-blocresection was not possible. The resected specimen was removed and sent for pathologic evaluation(Figure 1 C). The specimen was reviewed by a gastrointestinal pathologist and one or more residents in each hospital.

The EP site was observed for possible remnant lesions and immediate adverse events. Where remnant tissue was suspected, removal was performed with repeated biopsy, snaring, or thermal ablation with argon plasma coagulation (APC). In the event of immediate bleeding, epinephrine was sprayed with additional APC if bleeding persisted. In the event of duodenal perforation, endoscopic hemoclips were applied for the primary closure and surgery was subsequently performed. Sphinterotomies, BDS, and PDS were performed if needed (Figure 1 D). The procedure was terminated if there was no more residual tissue or in the absence of immediate adverse events. Subsequently, the patient was observed on the ward with physical examination, monitoring of vital signs, laboratory tests, and X-rays for early adverse events. The details of each endoscopic procedure were determined by the endoscopist.

All patients underwent routine follow-up after EP. Within 3 mo of the procedure, patients underwent endoscopic surveillance for assessment of remnant tissue and recurrence, and stent removal (Figure 1 E).Biopsy was performed if any remnant lesion was suspected. If the biopsy result showed remnants or early recurrence, additional therapeutic plans were decided by the endoscopist with the patient(Figure 1 F). If no abnormal lesion was identified, the patient underwent further surveillance at sixmonthly intervals for the first two years and annually thereafter.

Outcome measures

EP results included the resection specimen size, pathologic findings, accuracy of endoscopic biopsy,resection margin, curative resection, early and late recurrence, re-recurrence, endoscopic success, mean hospital stay, and mean adenoma-free period. EP outcomes were obtained from pathologic reports and medical charts.

Curative resection was defined as complete endoscopic resection without recurrence during followup. Early recurrence was defined as reconfirmed adenoma following biopsy at the first surveillance endoscopy. Late recurrence was defined as reconfirmed adenoma following biopsy after the first surveillance endoscopy. Re-recurrence was defined as recurrence of adenoma at the follow-up biopsy after the treatment of early or late recurrence. Endoscopic success was defined as treatment of AA with endoscopy, including cases with residual tissue, recurrence or complications, without surgical intervention. Resection margins were categorized into 3 groups, negative, positive, and uncertain, and they were analyzed as positive/uncertain group and negative group[17 ,18 ].

Adverse events of EP were categorized into early events (pancreatitis, delayed bleeding, cholangitis,and perforation) occurring within 30 d of the procedure and late events (papillary stenosis and death)occurring after 30 d following the procedure. Endoscopic adverse events and their severity were graded according to the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy criteria[19 ]. We set the minimum follow-up duration to one year to avoid underestimation of recurrence and adverse events. Univariate analysis and multivariate analysis were performed to evaluate the risk factors of early and late recurrence, non-curative resection, and adverse events.

Figure 1 Endoscopic papillectomy of ampullary adenoma. A: Careful inspection of the ampulla was required before the procedure; B: Endoscopic papillectomy was performed using a conventional polypectomy snare; C: The resected specimen was retrieved and pinned on a cork with nails for pathological evaluation; D: The resected area was carefully inspected, and an additional procedure including common bile duct stenting (blue stent) or pancreatic duct stenting(green stent) was performed; E: Endoscopic surveillance was mandatory; F: If recurrence was suspected, additional treatment was considered.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean and standard deviation, and Categorical variables were expressed as a number and percentage. Univariate logistic regression analysis was performed to analyze the risk factors for early and late recurrences, non-curative resection, and adverse events. Variables that were significant in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate logistic regression analysis.APvalue < 0 .05 was considered significant. The probability of adenoma-free after EP was analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method. The statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS version 22 .0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA).

RESULTS

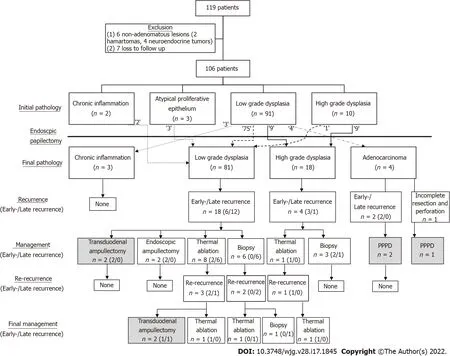

We retrospectively collected the medical records of 119 patients and their follow-up data (Figure 2 ). We excluded seven patients who failed to meet the follow-up criteria or were lost to follow-up within a year of the procedure, and six patients because of non-adenomatous lesions. After the exclusion criteria were applied, 106 patients were finally included for analysis.

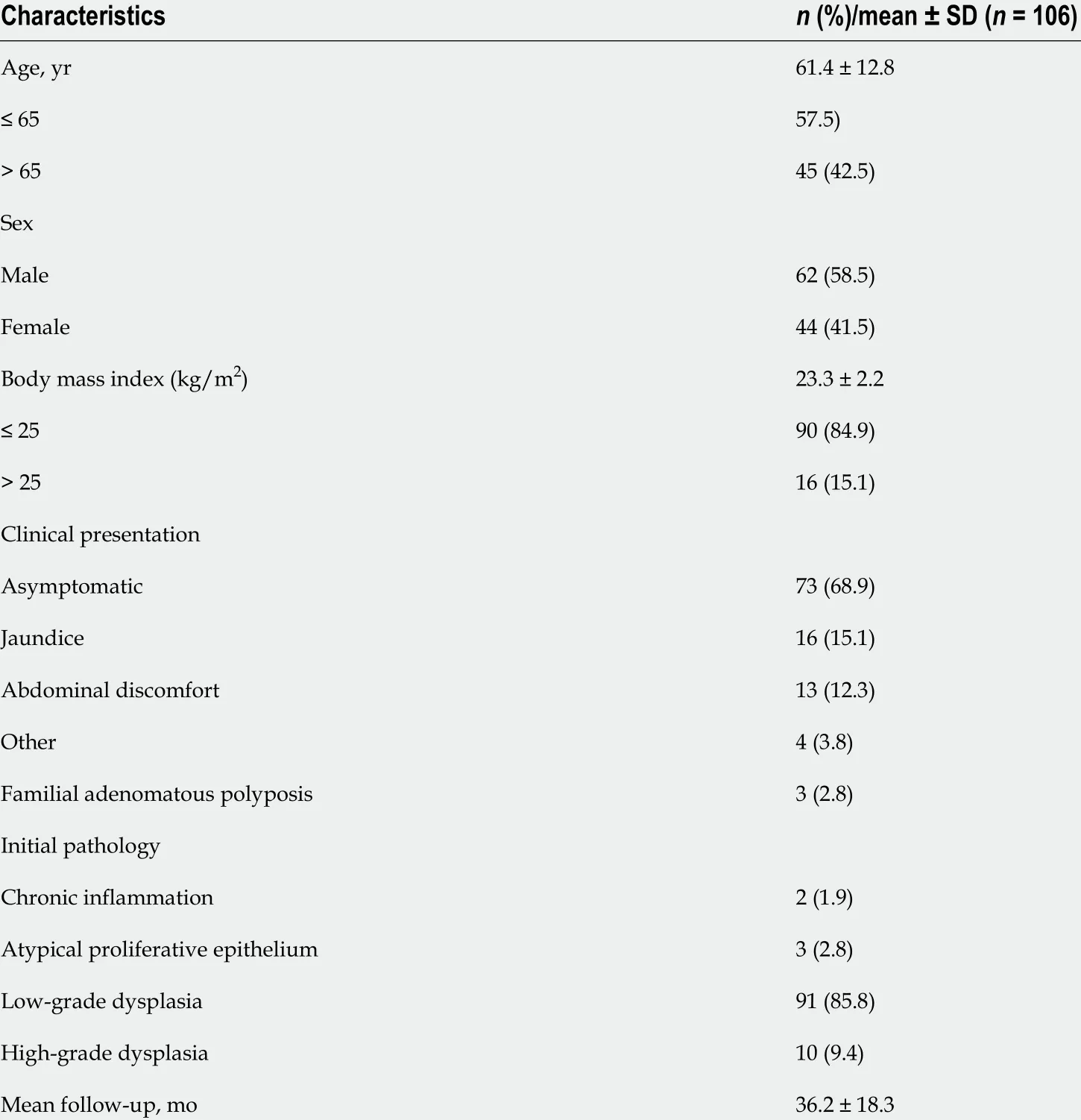

Patient baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1 . Seventy-three patients (68 .9 %) were asymptomatic, and AA was diagnosed incidentally from screening endoscopy or CT scan. The most frequent symptoms associated with AA were jaundice in 16 patients (15 .1 %) and abdominal discomfort in 13 patients (12 .3 %). All patients underwent biopsy before the EP procedure, and their pathology reports were as follows: chronic inflammation in 2 patients (1 .9 %), atypical proliferative epithelium in 3 patients (2 .8 %), adenoma with low-grade dysplasia in 91 patients (85 .8 %), and adenoma with highgrade dysplasia in 10 patients (9 .4 %).

The EP techniques used for the patients are listed in Table 2 . EUS was performed in 37 patients(34 .9 %), and a cholangiogram and pancreatogram were obtained in 70 patients (66 .0 %) and 87 patients(82 .1 %), respectively. Four patients (3 .8 %) underwent submucosal lifting with normal saline.En-blocresection was performed in 90 patients (84 .9 %), and piecemeal resection was performed in 16 patients(15 .1 %). After the resection, thermal ablation was performed in 24 patients (22 .6 %) because of remnant tissue or immediate bleeding. Complete endoscopic resection was successfully performed in 105patients (99 .1 %), and in one patient the lesion could not be completely removed due to underlying fibrosis and a diagnosis of adenocarcinoma was finally made. BDS and PDS were performed in 25 patients (23 .6 %) and 78 patients (73 .6 %), respectively.

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of patients

Table 2 also summarizes the results of the EP. The mean size of the resected specimen was 13 .6 ± 5 .5 mm, and the final pathologic results were as follows: chronic inflammation in 3 cases (2 .8 %), low-grade dysplasia in 81 cases (76 .4 %), high-grade dysplasia in 18 cases (17 .0 %), and adenocarcinoma in 4 cases(3 .8 %). Figure 2 shows the diagnostic discrepancies between the initial and final pathologies. Lesions that showed chronic inflammation or atypical proliferative epithelium on initial biopsy were all lowgrade dysplasia on final diagnosis. Out of 91 cases of low-grade dysplasia on the initial biopsy, the final pathologic results were chronic inflammation in three cases (2 .8 %), low-grade dysplasia in 75 cases(82 .4 %), high-grade dysplasia in 9 cases (9 .9 %), and adenocarcinoma in four cases (3 .8 %). Out of 10 cases of high-grade dysplasia on the initial biopsy, the final pathologic results were low-grade dysplasia in one case and high-grade dysplasia in nine cases. Endoscopic biopsy was accurate in 84 patients (79 .2 %),with underestimation in 18 patients (17 .0 %) and overestimation in 4 patients (3 .8 %).

R0 resection was achieved in 84 patients (79 .2 %), and curative resection was achieved in 81 patients(76 .4 %). Early recurrence was found in 11 patients (10 .4 %), late recurrence was found in 13 patients(12 .3 %), and all recurrences were local lesions. Re-recurrence occurred in six patients (5 .7 %), and patient characteristics are summarized in Supplementary Table 1 . Figure 2 also shows the number of early and late recurrences from final pathologic results, how these cases were managed, how many re-recurrences occurred after the initial management, and final management of re-recurrences.

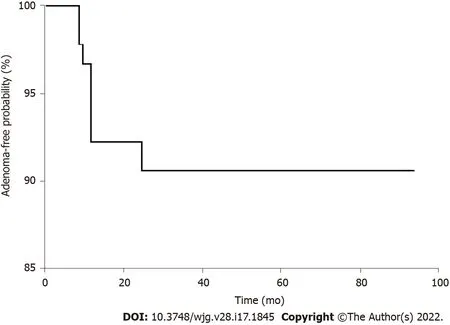

Initial management of the 11 patients with early recurrence involved endoscopic therapy in 7 cases(two EPs, two biopsies, and three thermal ablations) and surgery in four cases [two transduodenal ampullectomies (TA) and two pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomies (PPPD)]. Three patients with re-recurrence were managed with thermal ablation (two cases) and TA (one case). The 13 patients with late recurrence were initially managed endoscopically (six biopsies and seven ablations), and three patients with re-recurrence underwent thermal ablation, biopsy, and TA, respectively. Altogether, 99 patients (93 .4 %) were managed by endoscopy alone, and seven patients (6 .6 %) underwent additional surgical management: four patients due to a remnant lesion, two patients due to re-recurrence, and one patient due to incomplete resection and perforation (Figure 2 ). The mean adenoma-free period was 29 .6± 21 .3 mo, and the adenoma-free survival is shown in Figure 3 . Except for a patient who showed recurrence after 27 mo of the EP procedure, 12 patients (92 .3 %) experienced recurrence within a year of the EP procedure.

Table 2 Techniques and outcomes of endoscopic papillectomy

Figure 2 Flowchart of the study. After applying the exclusion criteria, 106 patients were enrolled, showing the correlation between the initial and final pathology.After the procedure, remnant and recurrent lesions were identified in follow-up surveillances. Most of these lesions were successfully managed with endoscopy. The gray-colored box indicates surgical management.

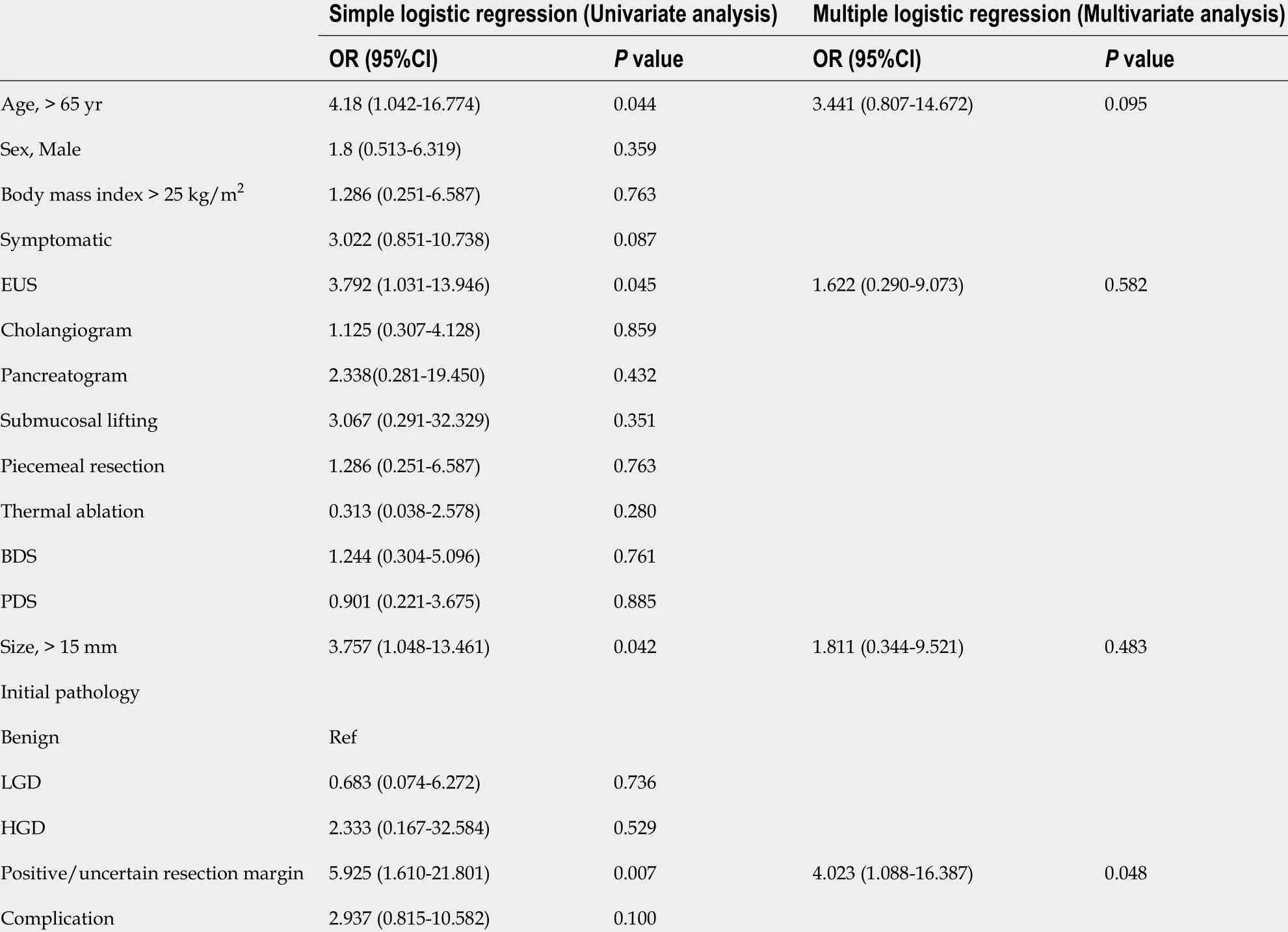

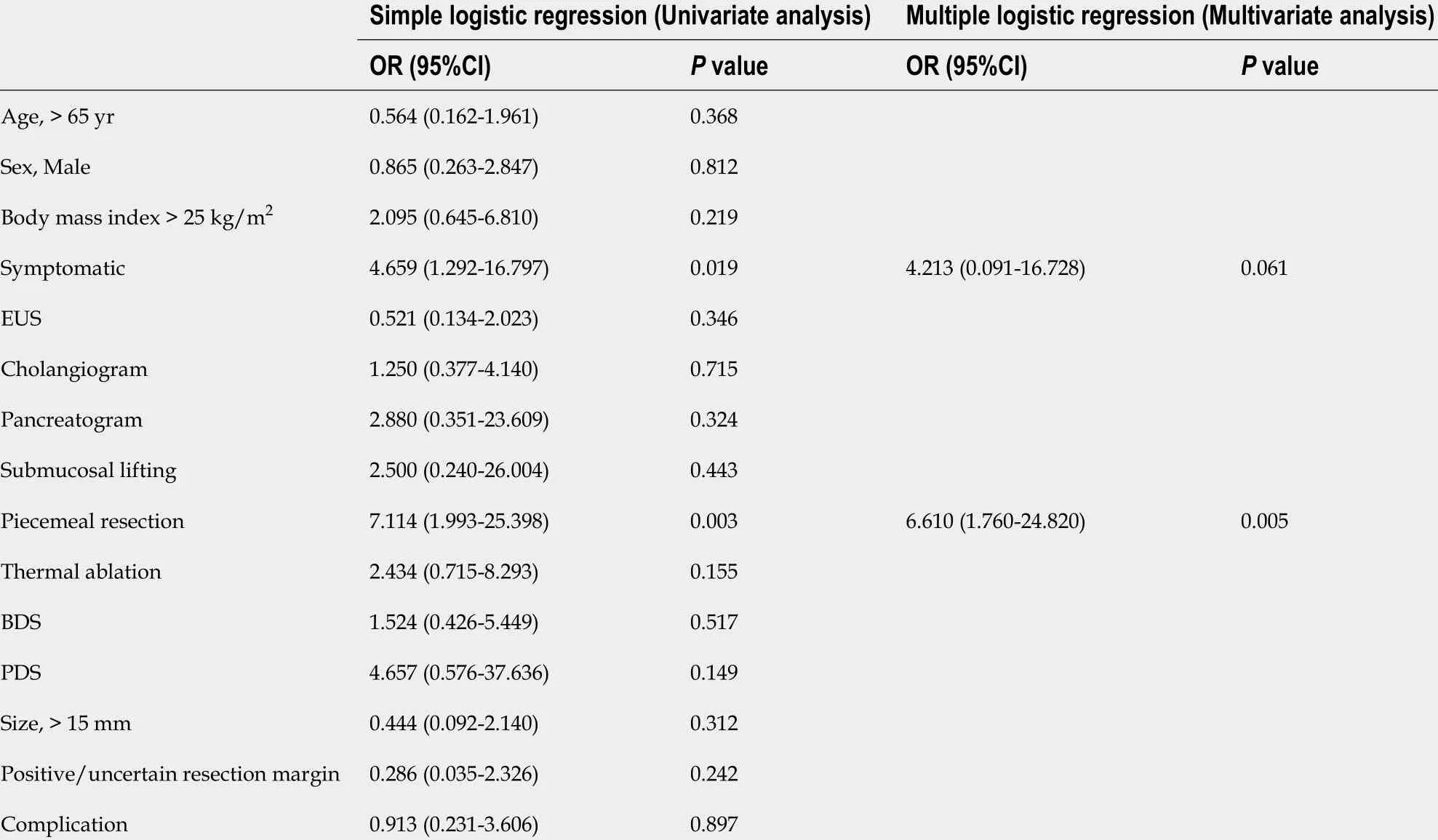

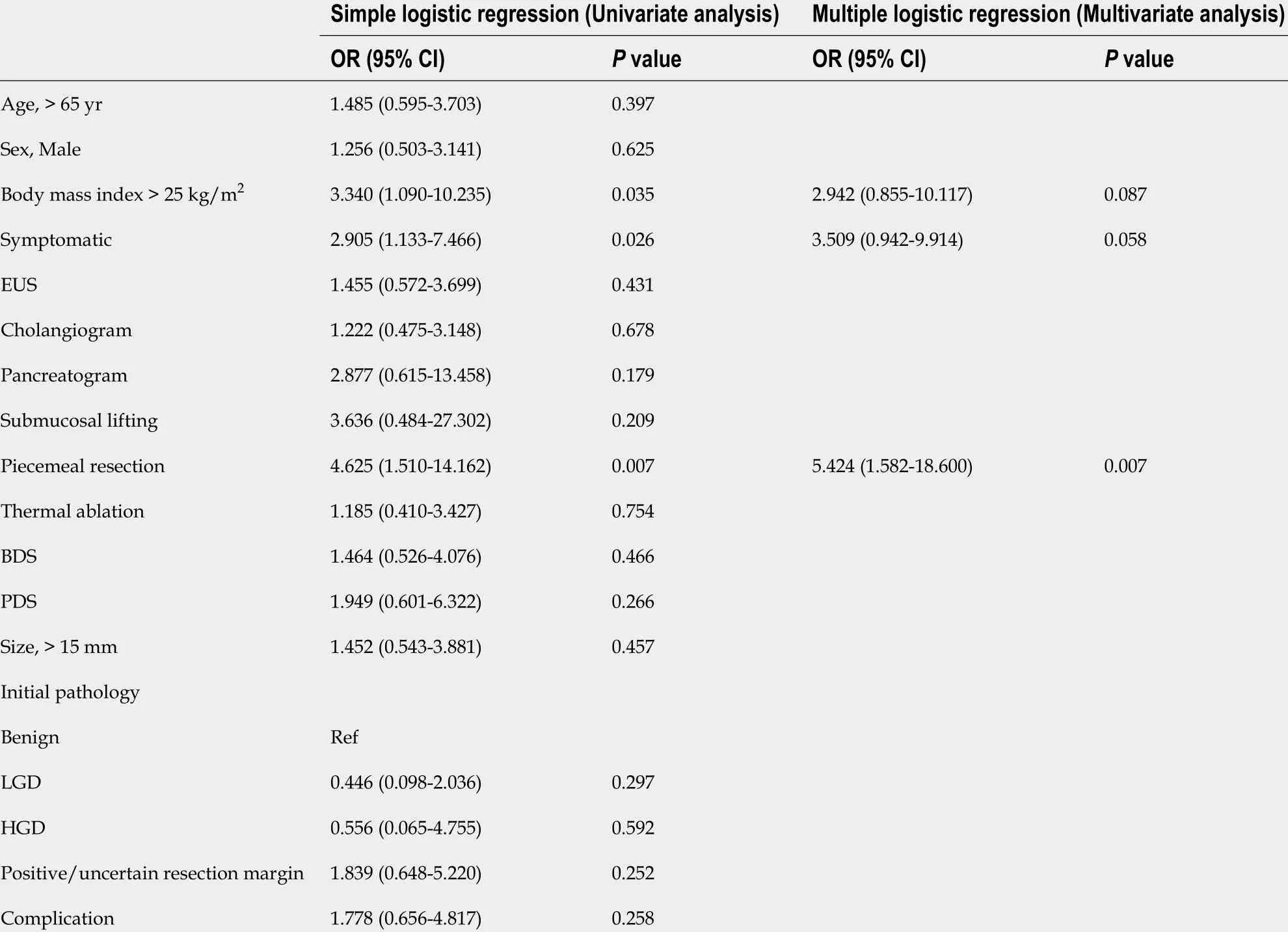

Table 3 , Table 4 , and Table 5 show the univariate and multivariate analysis of the risk factors for early recurrence, late recurrence and non-curative resection, respectively. Age over 65 , EUS, size > 1 .5 cm and positive/uncertain resection margin were statistically significant risk factors for early recurrence in univariate analysis, and positive/uncertain resection margin [Odds ratio (OR) = 4 .023 ; 95 %CI: 1 .088 -16 .387 ; P = 0 .048 ] was the significant factor for early recurrence in multivariate analysis. Presence of symptom (OR = 4 .659 ; 95 %CI: 1 .292 -16 .797 ; P = 0 .019 ) and piecemeal resection (OR = 7 .114 ; 95 %CI:1 .993 -25 .398 ; P = 0 .003 ) were significant risk factors for late recurrence in univariate analysis, and piecemeal resection (OR = 6 .610 ; 95 %CI: 1 .760 -24 .820 ; P = 0 .005 ) was the only significant factor for late recurrence in multivariate analysis. Body mass index over 25 , presence of symptom, and piecemeal resection were significant risk factors for non-curative resection, and multivariate analysis showed that piecemeal resection (OR = 5 .424 ; 95 %CI: 1 .582 -18 .600 ; P = 0 .007 ) was a significant risk factor for noncurative resection.

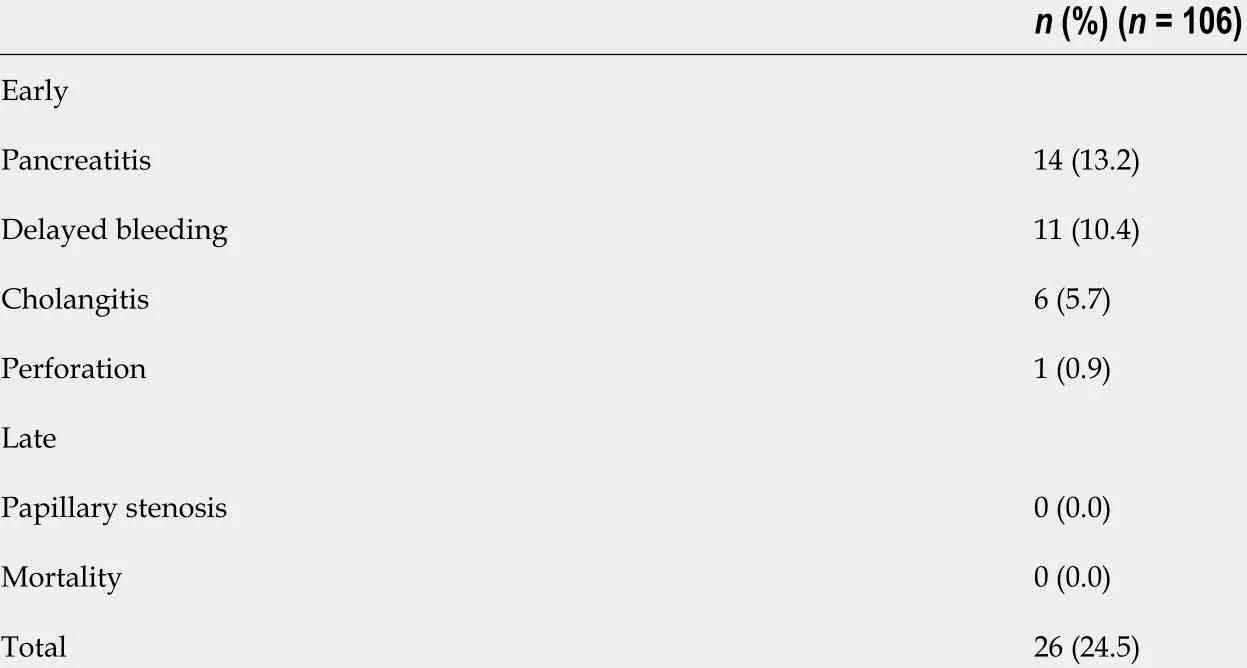

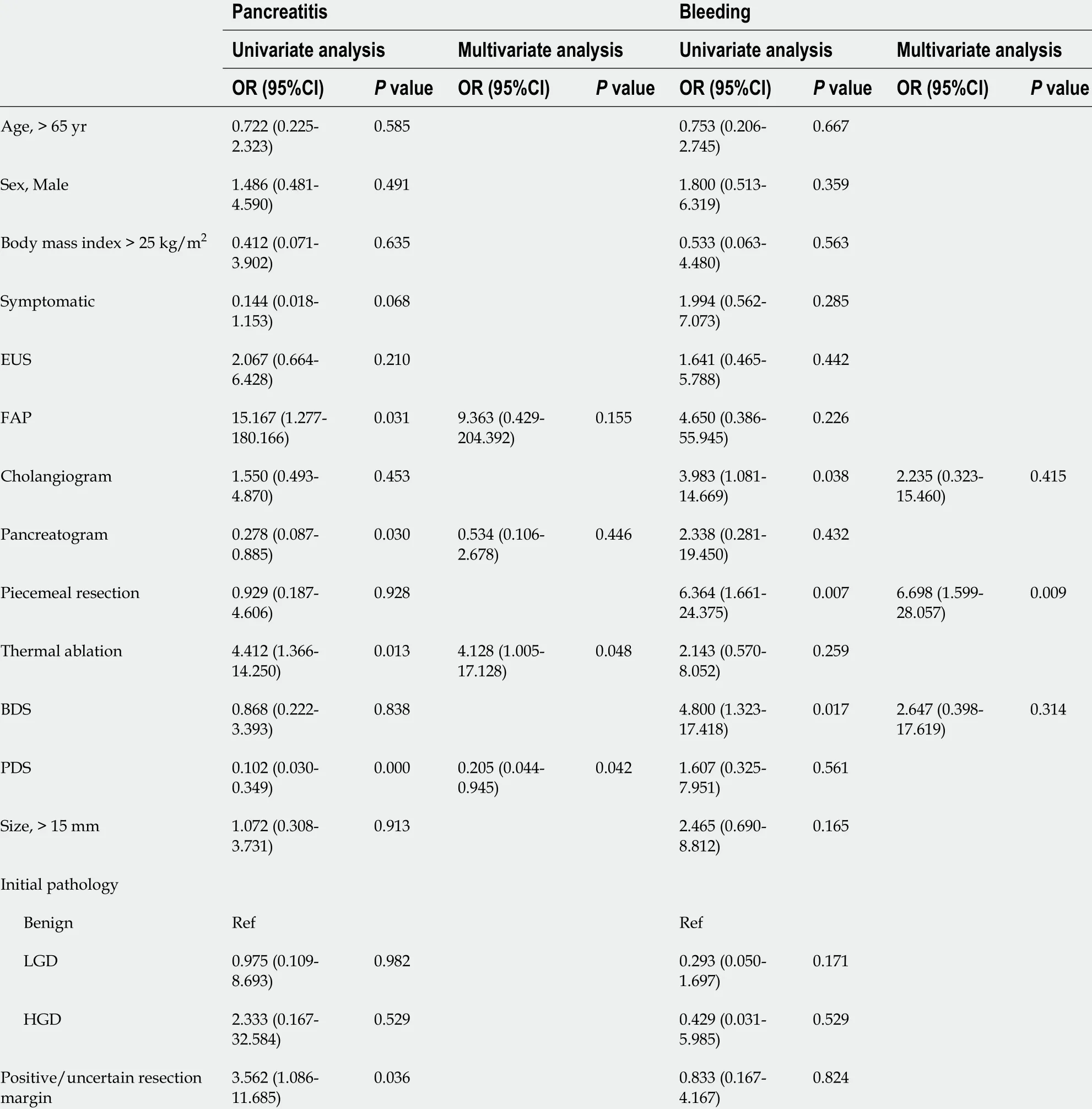

Altogether, adverse events occurred in 26 patients as shown in Table 6 . Early adverse events were as follows: pancreatitis in 14 patients (13 .2 %), delayed bleeding in 11 patients (10 .4 %), cholangitis in six patients (5 .7 %), and perforation in one patient (0 .9 %). No late adverse events were reported. In most cases, the severity of adverse events was classified as either mild or moderate, except for one case with perforation. Table 7 shows the univariate and multivariate analysis of risk factors for adverse events,including pancreatitis and delayed bleeding. FAP, pancreatogram, thermal ablation and PDS were significant risk factors for pancreatitis in univariate analysis, and in multivariate analysis, thermal ablation (OR = 4 .128 ; 95 %CI: 1 .005 -17 .128 ; P = 0 .048 ) was a positive risk factor, while PDS (OR = 0 .205 ;95 %CI: 0 .044 -0 .945 ; P = 0 .042 ) was a negative risk factor for pancreatitis. Cholangiogram, piecemeal resection, and BDS were significant risk factors for delayed bleeding in univariate analysis, and piecemeal resection (OR = 6 .698 ; 95 %CI: 1 .1 .599 -28 .057 ; P = 0 .009 ) was the only significant risk factor in multivariate analysis. No significant risk factor for cholangitis or perforation was identified.

Table 3 Risk factors of early recurrence

DISCUSSION

Of the 106 patients, curative resection was performed in 81 patients (76 .4 %) with 26 cases of adverse events (24 .5 %), 11 early recurrences (10 .4 %), 13 Late recurrences (12 .3 %), and 6 re-recurrences (5 .7 %).Our results were consistent with those of previous studies showing curative resection rates of 73 .0 %-82 .7 %, adverse events rates of 15 .0 %-43 .6 %, early recurrence rates of 2 .7 %-19 .0 %, and late recurrence rates of 0 -23 .9 %[14 ,20 -23 ]. There are large variations in the reported outcomes, particularly among studies involving small numbers of cases because there is no consensus on which parameter best represents the performance of EP. The parameters used in previous studies are inconsistent, and inclusion criteria for EP vary.

Factors used for the evaluation of outcomes in previous studies include visual resection margin,histologic resection margin, recurrence, adverse events, need for surgery, and combinations of these factors. We suggest that curative resection (negative visual resection margin and no recurrence), adverse events, and endoscopic success (negative visual resection margin and no need for surgery) best represent the outcomes of EP. An ideal outcome for EP is the achievement of complete removal of the AA, without adverse events, and without recurrence, which is curative resection with no adverse event.Moreover, even in the event of recurrence, most of these patients can be and are managed endoscopically, representing cases of endoscopic success. We attempted to identify the factors that could predict and improve these outcomes.

In 84 patients (79 .2 %) the initial and final pathologic results were consistent, which is comparable to previously reported studies[20 ,23 ]. The initial biopsy result for the four patients with adenocarcinoma was reported as low-grade dysplasia. Biopsies of AA can occasionally be insufficient because the biopsy is often performed using a forward-viewing endoscope, making a targeted biopsy difficult. Therefore,even if the initial result is benign, it is important to remove the lesion completely with an adequate margin-free area in case of malignancy.

The ampullary lesions found after EP are often described as remnant/residual or recurrence in the literature[14 ,20 ,22 -24 ]. Currently, these two categories are clinically distinguished according to thetiming of lesion discovery: most studies define remnant/residual as the part of the previous lesion found at the first or any surveillance endoscopy performed 3 -6 mo after EP, and recurrence as the lesion found after the first surveillance endoscopy or 6 mo after EP. Both are confirmed histologically. There is a clear difference between these definitions as remnant/residual refers to the remaining part of the pathologic lesion, while recurrence refers to a pathologic lesion that is newly developed after the procedure[25 ]. However, it is often difficult to separate these cases clinically. Diagnosis of a remnant could be delayed and the lesion may be found after the first surveillance endoscopy for a number of reasons including small size of remnant tissues and tissue burn from the procedure, and the delay in diagnosis leads to underestimation of remnant/residual lesions and overestimation of recurrence cases[18 ]. Considering a newly identified lesion at the first surveillance endoscopy as a remnant/residual in R0 resection may also be controversial. Therefore, instead of labeling these two groups differently, it is preferable to refer to both lesions as recurrence and distinguish these cases according to the timing of diagnosis. The recent European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guideline states that up to two thirds of recurrences are early recurrences[15 ].

Table 4 Risk factors of late recurrence

These two groups differ in terms of the timing of the diagnosis and clinical implications, and there may also be differences in patient management. Recurrences were managed at the endoscopist’s discretion using various strategies, including endoscopic and surgical management. Except for early recurrence from adenocarcinoma that was managed with PPPD, it was difficult to identify which factors were considered for a particular treatment. However, early recurrences tend to be managed more aggressively than late recurrences, although the numbers were small for comparisons to be statistically significant (3 vs 1 TA and 2 vs 0 additional EP for earlyvslate recurrences). This tendency may be explained in that in cases of early recurrence, the initial removal of the lesion has been incomplete, so more invasive treatment may be required compared to the previous treatment method. Conversely, late recurrences are newly developed lesions that are typically small or are early lesions.

It is often difficult to establish which area of the adenoma is responsible for the recurrence because recurrences are typically small, but it can be presumed that they occur from the bile duct, pancreatic orifice, base of ampulla, or resection margin. Reported risk factors for recurrence include age, sex, FAP,intraductal involvement, incomplete resection, piecemeal resection, and final pathology, although the results of these studies are rather inconsistent[13 ,23 ,25 -27 ]. Here, a positive/uncertain resection margin in the pathologic report was a significant risk factor for early recurrence, and piecemeal resection was a significant risk factor for late recurrence. This is the first study to analyze the risk factors for both early and late recurrence, considering the different definitions and characteristics of recurrence. A positive resection margin could increase the risk of remnants at the resection margin, but this association was not found to be significant in previous studies[25 ]. This may be because the positive margin following an EPprocedure is occasionally unreliable, as the resected lesions are often too small to be properly manipulated, and cauterization may mask a positive margin[17 ]. Also, many previous studies do not clearly state how they analyzed the lesion with uncertain margin. More studies are needed to understand the clinical implications of a positive/uncertain resection margin and develop further management strategies for margin-positive/uncertain lesions. Additionally, to reduce recurrence after EP, it is important to check the peripheral and deep margin of the lesion meticulously before the EP,including intraductal involvement, and secure the resection margin properly during the EP. This is because recurrence could be caused by the poor selection of patients or inability to secure the marginduring the procedure, which is sometimes inevitable due to the characteristics of the lesion or the procedure itself. A more aggressive procedure could secure an adequate margin but may cause adverse events such as perforation, so proper selection of patients and careful approaches are mandatory.Similar considerations apply to the higher risk of late recurrence in piecemeal resection. In piecemeal resection, the resection margin may be unreliable, and a thorough evaluation and follow-up for recurrence is required. Piecemeal resection was a significant risk factor for non-curative resection,meaningen-blocresection is a significant protective factor for curative resection, while a pathologic margin was not significant. A positive/uncertain margin and piecemeal resection are important factors for recurrence prediction, although their negative predictive values were 79 .8 % and 77 .4 %, respectively;thus, curative resection cannot be assumed in lesions with a negative margin oren-blocresection.

Table 5 Risk factors of non-curative resection

Table 6 Adverse events of endoscopic papillectomy

Table 7 Univariate and multivariate analysis of risk factors for pancreatitis and bleeding

Interestingly, our study was the first to compare the effects of factors including hospital setting and endoscopist experience on the outcome of EP (Supplementary Table 2 ), and these were not significant for remnant, recurrence, or adverse events. These findings suggest that there was no significant difference in EP results between hospitals with a certain volume of ERCP cases and endoscopists with a certain level of experience. Further studies with larger number of patients are needed to support our suggestion.

Figure 3 Adenoma-free survival after endoscopic papillectomy. The vertical axis of the graph indicates the adenoma-free probability, and the horizontal axis shows time to remnant or recurrence after endoscopic papillectomy. The longest adenoma-free period before recurrence was 27 mo, and the longest adenomafree period without recurrence was 94 mo.

Of the six patients with re-recurrence, two patients experienced re-recurrence even after a further session of endoscopic treatment and underwent surgery. Patients with persistent AA showed no specific features to guide the early prediction of the lesion characteristics and early transition to more invasive therapy. The finding that EUS was performed in both patients with re-recurrence suggests that EUS may not adequately predict recurrence or persistence. Moreover, it is unclear as to what extent a benign,although premalignant, AA lesion should be treated at recurrence, considering the adverse events associated with the available treatments. High-quality recommendations or guidelines are necessary.

Our results showed that most adverse events caused by EP showed mild- to moderate-grade severity.The role of thermal ablation in bleeding remains controversial and studies have shown that the risk of pancreatitis increased with the size of the lesion and when hemostasis was performed[22 ,23 ,28 ]. Here,thermal ablation was not significantly associated with bleeding or recurrence although it increased the risk of pancreatitis. The role of PDS is still under debate, but results of several studies, including ours,advocate the use of PDS for prophylaxis of pancreatitis[29 -31 ]. Moreover, no pancreatic stenosis was observed, and this could be explained by our relatively high PDS rate at 73 .6 %. Hence, it is expected that PDS will help prevent pancreatitis and pancreatic stenosis, and we recommend routine pancreatic stenting, if possible. Also, our result showed that piecemeal resection was the only significant risk factor for delayed bleeding. Piecemeal resection was performed for lesions whereen-blocresection was impossible, therefore, the lesions with piecemeal resection tend to be larger[32 ]. A previous study did not show the correlation between piecemeal resection and bleeding, based on the small number of piecemeal resection cases, but colonic lesions with piecemeal resection show significant bleeding during endoscopic mucosal resection[32 ,33 ]. Further research is needed to support the role and adverse events of piecemeal resection in endoscopic papillectomy.

Our study has several limitations. As the indications for EP have not been established, selection bias could not be avoided. Moreover, due to the lack of guidelines on the optimal EP technique, several decisions made during the procedure were at the discretion of the endoscopist. Not all hospitals distinguished margin-positive cases as vertical or lateral involvement, therefore, we simplified the involvement of the margin as positive/uncertain or negative. Finally, the study design was retrospective, and factors regarding the procedure and follow-up could not be controlled.

CONCLUSION

EP is a feasible treatment option for AA with high technical success. However, diagnostic discrepancy,remnant lesions, recurrence, and adverse events cannot be neglected. Unlike gastric or colon adenoma resection, even in cases of complete resection, remnant lesions, recurrence, and re-recurrence were identified, emphasizing the importance of follow-up. For patients with a positive/uncertain resection margin in particular, close follow-up for early recurrence is required, and the possibility of late recurrence should be considered in patients with piecemeal resection. Especially in patients with a positive/uncertain resection margin or piecemeal resection, the possibility of recurrence should be considered, and closer follow-up for recurrence is required.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Choi SJ and Lee HS carried out the concept and design, drafting of the article, and critical revision; Choe JW, Lee JM, Hyun JJ, and Yoon JH collected the data; Kim J, Kim HJ, Kim JS, Choi HS carried out data analysis and interpretation; and all authors approved the final version of the article.

Supported byNational Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by the Korean Government, No. NRF-2021 M3 E5 D1 A01015177 ; and National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by the Ministry of Education, No.NRF-2018 R1 D1 A1 B07048202 .

Institutional review board statement:The study protocol was consistent with the guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional review boards of each participating institution.

Informed consent statement:Patients were not required to give informed consent to the study because the analysis used anonymous clinical data that were obtained after each patient agreed to treatment by written consent.

Conflict-of-interest statement:Authors declare no conflict of interest in this article.

Data sharing statement:No additional unpublished data are available.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4 .0 ) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4 .0 /

Country/Territory of origin:South Korea

ORCID number:Seong Ji Choi 0000 -0002 -1969 -516 X; Hong Sik Lee 0000 -0001 -9726 -5416 ; Jiyeong Kim 0000 -0002 -7969 -1419 ; Jung Wan Choe 0000 -0002 -8371 -9672 ; Jae Min Lee 0000 -0001 -9553 -5101 ; Jong Jin Hyun 0000 -0002 -5632 -7091 ; Jai Hoon Yoon 0000 -0003 -3194 -5149 ; Hyo Jung Kim 0000 -0003 -3284 -3793 ; Jae Seon Kim 0000 -0002 -2012 -6781 ; Ho soon Choi 0000 -0002 -5257 -3586 .

S-Editor:Wang JL

L-Editor:A

P-Editor:Wang JL

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年17期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年17期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Could microbiome analysis be a new diagnostic tool in gastric carcinogenesis for high risk, Helicobacter pylori negative patients?

- Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha activation and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibition target dysbiosis to treat fatty liver in obese mice

- Sirtuin1 attenuates acute liver failure by reducing reactive oxygen species via hypoxia inducible factor 1 α

- Gut homeostasis, injury, and healing: New therapeutic targets

- New insights in diagnosis and treatment of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms

- Biliary metal stents should be placed near the hilar duct in distal malignant biliary stricture patients