Translation and piloting of the Chinese Mandarin version of an intensive care-specific pressure injury risk assessment tool (the COMHON Index)

Josphin Lovrov , Paul Fulbrook , Sandra J.Mils , Michal Stl ,Xian-Lian Liu , Lin Zhan , Anl Cobos Varas

a School of Nursing, Midwifery & Paramedicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, Australian Catholic University, Banyo, Australia

b Nursing Research and Practice Development Centre, The Prince Charles Hospital, Chermside, Australia

c Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

d School of Allied Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, Australian Catholic University, Banyo, Australia

e College of Nursing and Midwifery, Charles Darwin University, Brisbane, Australia

f Nursing Department, Shanghai Tenth People's Hospital, Shanghai, China

g Critical Care Department, San Cecilio University Hospital, Granada, Spain

Keywords:Critical care Intensive care units Nursing care Pressure injury Pressure ulcer Risk assessment Translating

ABSTRACT Objective: To translate an intensive care-specific pressure injury risk assessment tool (the COMHON Index) from English into Chinese Mandarin.Methods: A four-step approach to instrument translation was utilised: 1) English-Mandarin forwardtranslation by three independent bilinguists; 2) Mandarin-English back-translation by two other independent bilinguists;3)comparison of forward and back-translations,identification of discrepancies,with required amendments returned to step one;and 4)piloting of the translated instrument.The pilot study was undertaken in a Chinese surgical intensive care unit with a convenience sample of 20 nurses.A fivepoint ordinal scale (1 =very difficult;5 =very easy) was used to assess ease-of-use and understanding.Translations were retained where medians ≥4 indicated use and understanding was easy to very easy.Results: Five iterations of steps 1 to 3, and two sets of amendments to the original English instrument,were required to achieve translation consensus prior to pilot testing.Subscale scoring, sum scoring, and risk categorisation were documented in most pilot assessments (≥80%), but three sum scores were incorrectly tallied.The overall tool and all subscales were easy to use and understand(medians ≥4),and most assessments (16/20, 80%) took ≤5 min to complete.Thus, translations were retained, with minor amendments made to instrument instructions for scoring and risk categorisation.Conclusions: An easy-to-use Chinese Mandarin intensive care-specific pressure injury risk assessment tool has been introduced through cross-cultural translation.However, it requires further testing of interrater reliability and agreement.A rigorous translation and reporting exemplar is presented that provides guidance for future translations.

What is known?

· Intensive care patients are at high risk of pressure injury.Pressure injury prevention is an essential component of patient safety and begins with a risk assessment.

· Pressure injury risk assessment in intensive care should be setting-specific.

· The COMHON Index is an intensive care pressure injury risk assessment tool which has demonstrated promising psychometric properties.

What is new?

· The COMHON Index has been translated into Chinese Mandarin using a rigorous approach.

· Most nurses who participated in the piloting process indicated it was relatively fast and easy to use and understand.

· It has widespread potential for use, but first requires further psychometric testing.

· Future translation work should employ appropriate methodology and reporting.

1.Introduction

1.1.Pressure injury in intensive care

Hospital-acquired pressure injury (PI) is considered an adverse event [1], with rates highest in intensive care units (ICUs) in comparison to wards [2].An international PI point prevalence study across 1,117 ICUs in 90 countries found an overall prevalence of 26.6%, with an ICU-acquired prevalence of 16.2% [3].This is of concern given the burdens associated with PI for individuals [4,5]and healthcare facilities [6].A secondary analysis of Labeau et al.’s[3]international point prevalence data found an ICU-acquired prevalence of 4.3% across 198 Chinese ICUs [7].Similarly, a study across 12 Chinese hospitals reported a hospital-acquired PI prevalence of 4.5%in an ICU sample of 1,094[8].Another Chinese study,across 25 hospitals from one province,reported a hospital-acquired PI prevalence of 1.4% in ICU (n =432) [9].While these rates of hospital-acquired PI in Chinese ICUs are lower than those reported globally [3], ICU-acquired PI nonetheless continues to be a challenge.

1.2.Risk assessment

Not all PIs are preventable[10],particularly in ICU[11],but most are avoidable using preventative interventions [12,13].The first step of PI prevention is risk assessment [14].Risk assessment may be aided with use of a PI risk assessment tool, but most do not include ICU-specific factors [15,16].Risk factors associated with PI in ICU include immobility, hypotension or impaired perfusion, vasopressors and extended mechanical ventilation [15,17,18].Recently, more ICU-specific tools have been developed and tested to some extent[e.g.19-21].Many tools are tested using predictive validity(i.e.whether a PI developed as predicted by assessed risk),but if preventative intervention use appropriately follows risk assessment and PI is thus prevented, predictive validity would be reflected as poor [22].Therefore, other tool properties require consideration, such as interrater reliability.

The COMHON Index is an ICU-specific PI risk assessment tool which has displayed other promising properties.It was developed in Spain,with content established by the researcher group based on international PI risk assessment tools and evidence relevant to PI risk factors in ICU[19].Following piloting,a tool with five subscales relevant to PI in ICU was finalised.Further testing was then undertaken in two Spanish hospitals, with the COMHON Index demonstrating positive interrater reliability (kappa 0.89-0.93),internal consistency (Cronbach’s α 0.72-0.80) and concurrent validity with the Braden (kappa 0.74-0.81)and Norton scales (kappa 0.72-0.73)[19].More recently in an Australian study,it was shown to have better interrater reliability(sum score intraclass correlation[ICC]0.90,risk level category ICC 0.87)than three non-ICU-specific tools (Braden sum score ICC 0.66; risk level category ICC 0.65;Norton sum score ICC 0.77;risk level category ICC 0.45; Waterlow sum score ICC 0.47; risk level category ICC 0.43) and was more sensitive to small changes in patient condition [16].An international Delphi study with a panel of ICU nurse experts has also matched the COMHON Index with a set of PI preventative interventions based on risk level [23].This is significant, as it is not risk assessment which prevents PI, but the subsequent use of preventative interventions based on identified risk [14,16].

In addition to the Spanish and English versions of the COMHON Index, work has been undertaken to translate and test a Japanese version(Y.Ikematsu,personal communication).While English and Spanish are the first and fourth most spoken languages respectively(native and non-native speakers), Chinese Mandarin is the second most spoken language in this respect and the largest language when counting only native speakers [24].There is a need for an ICU-specific PI risk assessment tool in this language, and although the development of setting-specific tools is relevant, it has been argued that indiscriminately creating new health assessment instruments within languages and cultures is unjustified where there are already existing instruments [25].Indeed, the translation of instruments developed elsewhere is time- and resource-saving[25,26], and given the promising range of properties that the COMHON Index has demonstrated in Spanish and English, it is an appropriate tool to translate into Chinese Mandarin.

1.3.Translation approaches

Previous instrument translation has been reported poorly and methods have varied [27].Nonetheless, translation approaches should be as rigorous as possible using appropriate methodology to ensure quality and accuracy [25-29].Translation techniques may include: back-translation (source-target language translation [forward], then target-source translation [back]); committees (bilingual expert groups translate or review translation); a bilingual approach (original/translated instrument administered to bilingualists, comparison of responses); and pre-testing or piloting [26].These techniques, among others, may be selected and combined based on research requirements [26,27].However, consensus is lacking on a specific combination or ‘gold standard’ approach for cross-cultural translation and adaption of instruments [27]and self-report questionnaires [30].

Brislin’s [31]approach has been widely adopted and recommends a procedure for English to other language translations with several steps, including back-translation iterations, multi-rater version examination and mono/bilingual testing.However, Jones et al.[32]argued that Brislin’s approach was not efficient or accurate for languages with multiple dialects and suggested a revised approach with multiple translators from different regions, committees and bilingual testing.Meanwhile,Cha et al.[26]highlighted that both the models of Brislin [31]and Jones et al.[32]have the potential to require an unachievable number of bilingual translators and proposed a process including back-translation, a committee and monolingual pretesting.Numerous other variations of translation methodology have been reported for health,self-report and research instruments, with various additional techniques incorporated[e.g.25,28,29,33].While there is evidently no standard methodology, there is some key overlap among approaches, with many including back-translation, at least two forward-translation bilinguists and pilot testing.Therefore, only translation methods that included these three techniques were considered for use in this translation study,of which the most suitable was that of Cha et al.[26].

1.4.Aim

This study aimed to translate an ICU-specific PI risk assessment tool,the COMHON Index, into Chinese Mandarin.

2.Methods

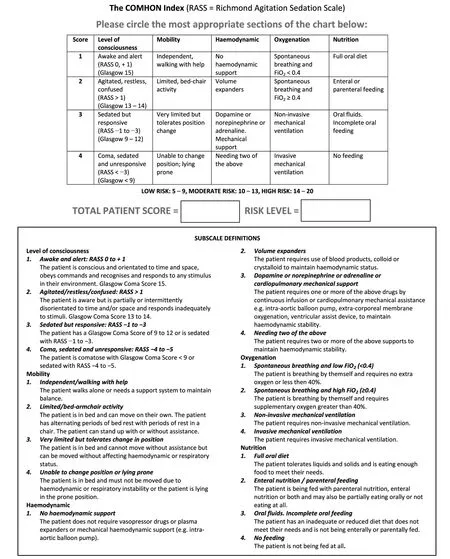

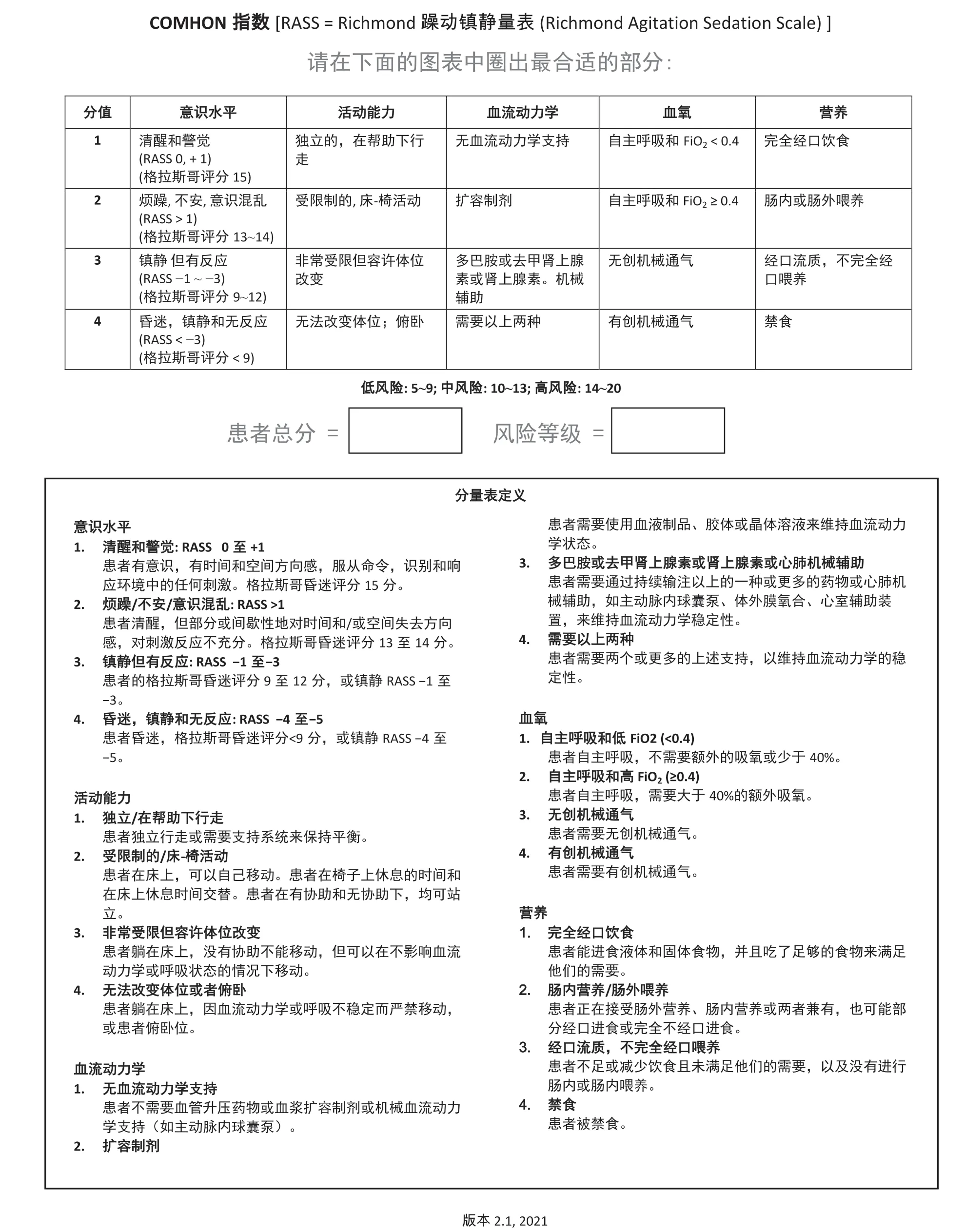

The COMHON Index [19]includes five subscales: level ofConsciousness (Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale [34]),Mobility,Haemodynamics,Oxygenation andNutrition.Each subscale has defined criteria and is scored from 1 to 4.The score of each subscale is then summed to determine risk level(low 5-9;moderate 10-13;high 14-20).Permission was granted by the lead author(A.Cobos Vargas),on behalf of the authors of the original COMHON Index,to translate the tool into Chinese Mandarin and publish the Chinese Mandarin and English versions.Ethical approval was granted as part of a larger project by the Human Research Ethics Committees of the Tenth People’s Hospital of Tongji University (SHSY-IEC-4.1/20-258/01) and Australian Catholic University (2021-17H).

2.1.Translation approach

Several modifications were made to the approach described by Cha et al.[26].Cha et al.[26]described their translators,but specific requirements for the inclusion of translators such as background and knowledge were not detailed.Given the nature of the COMHON Index,bilingual ICU nurses were required for most of the translator roles.Forward-translators were required to be native speakers of the target language(Chinese Mandarin)with a good understanding of the source language (English).Ideally back-translators would have converse language requirements [25,29,33].The following steps were employed (Appendix A).

2.1.1.Step 1 forward-translation

Three forward-translators independently translated the instrument from English into Chinese Mandarin.Forward-translators assessed each other’s versions, and differences were discussed in a forward-translator committee meeting.This was repeated until all forward-translators agreed on a final forward-translation version.

2.1.2.Step 2 back-translation

Two back-translators, who differed from the forwardtranslators, independently translated the Mandarin version back into English.While Cha et al.[26]reported the use of one backtranslator, we included two [28,29,32,33]to highlight discrepancies and facilitate a second committee approach.A monolingual investigator (English-speaking with over eight years’ nursing/research experience) compared the two back-translations to identify discrepancies, and the back-translators were given the opportunity to review each other’s versions.Any version discrepancies were discussed in a committee meeting of the back-translators and monolinguist investigator, and the two versions were synthesised into one back-translation version.

2.1.3.Step 3 comparison

The monolingual investigator, with assistance from two others(with extensive ICU nursing/research backgrounds), compared the synthesised back-translation version to the original English instrument.Detailed feedback of any identified discrepancies between the two was provided to the initial forward-translators.The lead COMHON Index developer answered queries where required.The forward-translators then amended the translation based on the feedback or provided justification for rejecting an amendment.Steps 1-3 were repeated for any identified discrepancies until the back-translation and original instrument were assessed to be equivalent in a ‘pre-final’ version.

Cha et al.[26]noted that their approach continued until the translation and original were identical with no errors in meaning.Given that the COMHON Index incorporates components which should not be adapted(e.g.prespecified scoring for haemodynamic criteria) an identical back-translation would, in part, be appropriate.However, consideration was also given to inherent differences between languages and interpretations.As the content of the COMHON Index was already established prior to translation and in line with the approach of Cha et al.[26], no further review of content was conducted outside of adaptions resulting from translation iterations.Content equivalence between original and translated phrases was considered in terms of Sechrest et al.’s[35]items of equivalence [26].

2.1.4.Step 4 pre-testing

The final step was to pilot the pre-final instrument in a sample representative of the intended population.While Cha et al.[26]pretested their translated instruments, the referenced ‘feedback form’ was not described with only internal consistency reported.However, measuring internal consistency with Cronbach's alpha may not be appropriate for the COMHON Index, given that each subscale is relevant to PI risk as a multi-dimensional construct,but not necessarily interrelated [36,37].Overall, piloting a translated instrument should assess clarity and ensure appropriate understanding [27-29].Thus, we developed a specific tool to pilot the COMHON Index translation to this end.If piloting indicated difficulties with subscale assessments or definitions, the relevant sections would be reviewed and amended with the translators.While further reliability and validity testing of the translated instrument would be required following finalisation and prior to clinical use,such testing should be separated from translation to ensure the adequate provision of detail in reporting [25].

2.2.Pilot study

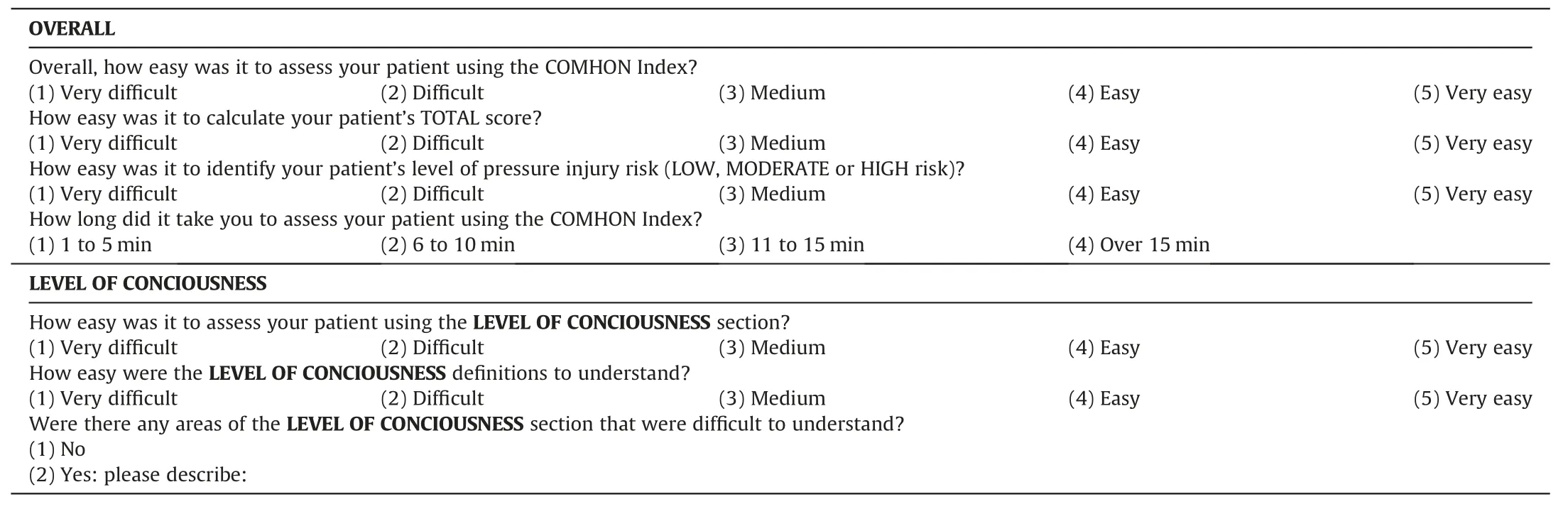

The setting was a 1,860-bed Class A tertiary comprehensive hospital in Shanghai, China, with five ICUs.Recommended pilot sample sizes vary,including ranges from 5[25]to 40[29,33],thus,the sample size was selected based on these recommendations and feasibility.Piloting was undertaken in the surgical ICU with a convenience sample of 20 ICU nurses.While some nurses may have coincidently been bilingual,it was anticipated that most would be monolingual.Standard PI risk assessment in the pilot setting included use of the Braden scale.Participating nurses, who provided written informed consent, were asked to assess one patient they were looking after with the pre-final Chinese Mandarin COMHON Index and complete a short questionnaire about instrument ease-of-use and understanding.While written informed consent was obtained by a local researcher,no identifying details or demographic data were collected in written assessment and questionnaire responses, and data analysers were not aware of participant identities.No patient data (except for assessments)were collected.Written instructions were provided with the COMHON Index, directing nurses to circle subscale assessments and document the sum score and corresponding risk level.The pilot study questionnaire,which comprised questions for the instrument overall and each subscale (Table 1), was then completed.

Table 1Pilot study questionnaire: overall instrument questions, subscale questions (presented for ‘Level of conciousness’ subscale).

2.3.Analysis

Translation iterations were reported narratively and summarised in a table.Pilot study data were entered into Microsoft Excel™for cleaning and checking by two independent individuals, then exported into IBM SPSS™(version 23) for analysis.Descriptive statistics were used to summarise instrument assessment completion and questionnaire responses.Translations for each subscale were retained where medians ≥4 indicated assessment and ease-of-use and understanding was ‘easy’ to‘very easy’.

3.Results

3.1.Translators

The three forward-translators were all native to China, with fluent English language skills.Two were ICU nurses(two-and nineyears’ practice) currently working within a Chinese ICU, one of whom was an investigator.The third, also an investigator, coordinated the forward-translation and was an accomplished nursing and health researcher with a nursing doctorate.

Difficulty was experienced in identifying translators who were native English- and secondary Chinese Mandarin-speakers.Thus,the two back-translators were native to China but based in Australia.One was a nurse with over ten years’ ICU experience in Australia, and previous experience as a theatre nurse within a Chinese hospital.The second had been residing in Australia for over six years and practicing as a perioperative nurse for over one year.Both completed undergraduate nursing qualifications in English.

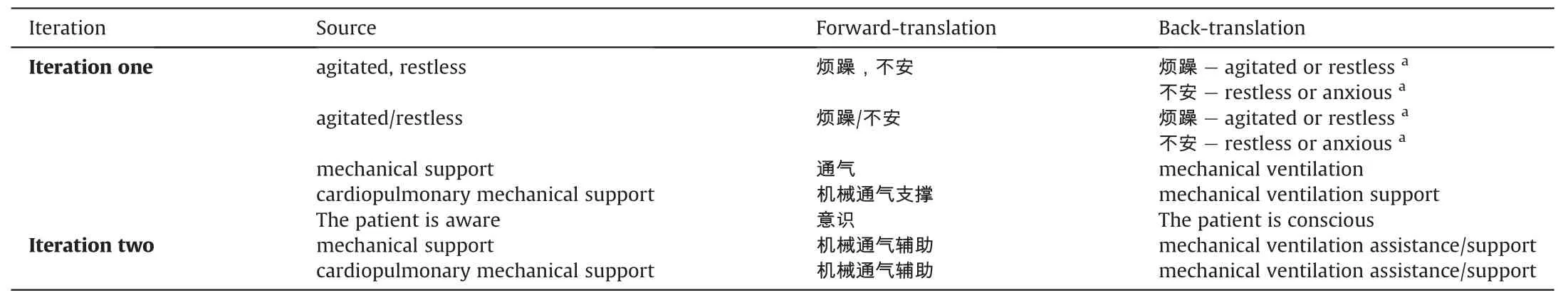

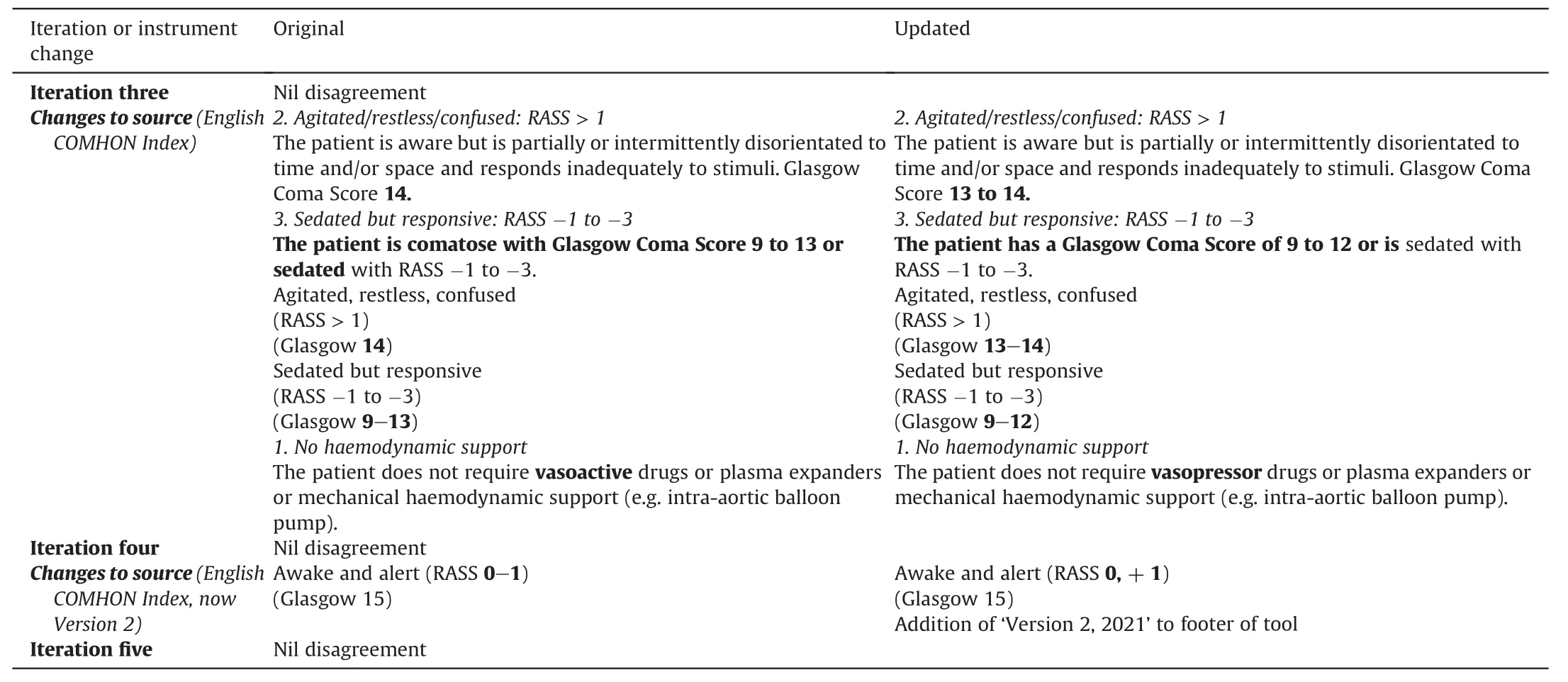

3.2.Iterations

Three iterations between translation steps 1 to 3 achieved successful translation of the majority of tool items.The first iteration resulted in five phrases being fed back to the forward-translators for amendment, and the second resulted in two (Table 2;Appendix B).Over the first three iterations, three items requiring clarification or amendment by the tool developer were noted.Subsequently, two sets of amendments were made to the source instrument, and Version 2 of the COMHON Index was established.The amendments to the source instrument were followed by forward- and back-translation iterations (iterations four and five), in which there were no disagreements.Following the fifth iteration,the translation was deemed equivalent,and a‘pre-final’translation was established.

3.3.Items of equivalence [35]

Some English words or phrases did not have identically matched Chinese Mandarin characters (vocabulary equivalence), and some differences in linguistic and cultural translations (experiential equivalence) and different word or phrase meanings between languages (conceptual equivalence) were noted.This was evident in Iteration one, where there was disagreement between backtranslators on the translation of two phrases (Table 2).Grammar and syntax are also vastly different between the languages(grammatical-syntactical equivalence).These challenges were overcome through identification and selection of the closest matching Mandarin characters (forward-translation), validation of the selection (back-translation) and subsequent consensus via iterations.No idioms (idiomatic equivalence) were identified.

Table 2aIteration disagreements and instrument changes(iterations one and two).

Table 2bIteration disagreements and instrument changes(iterations three to five).

3.4.Pilot results

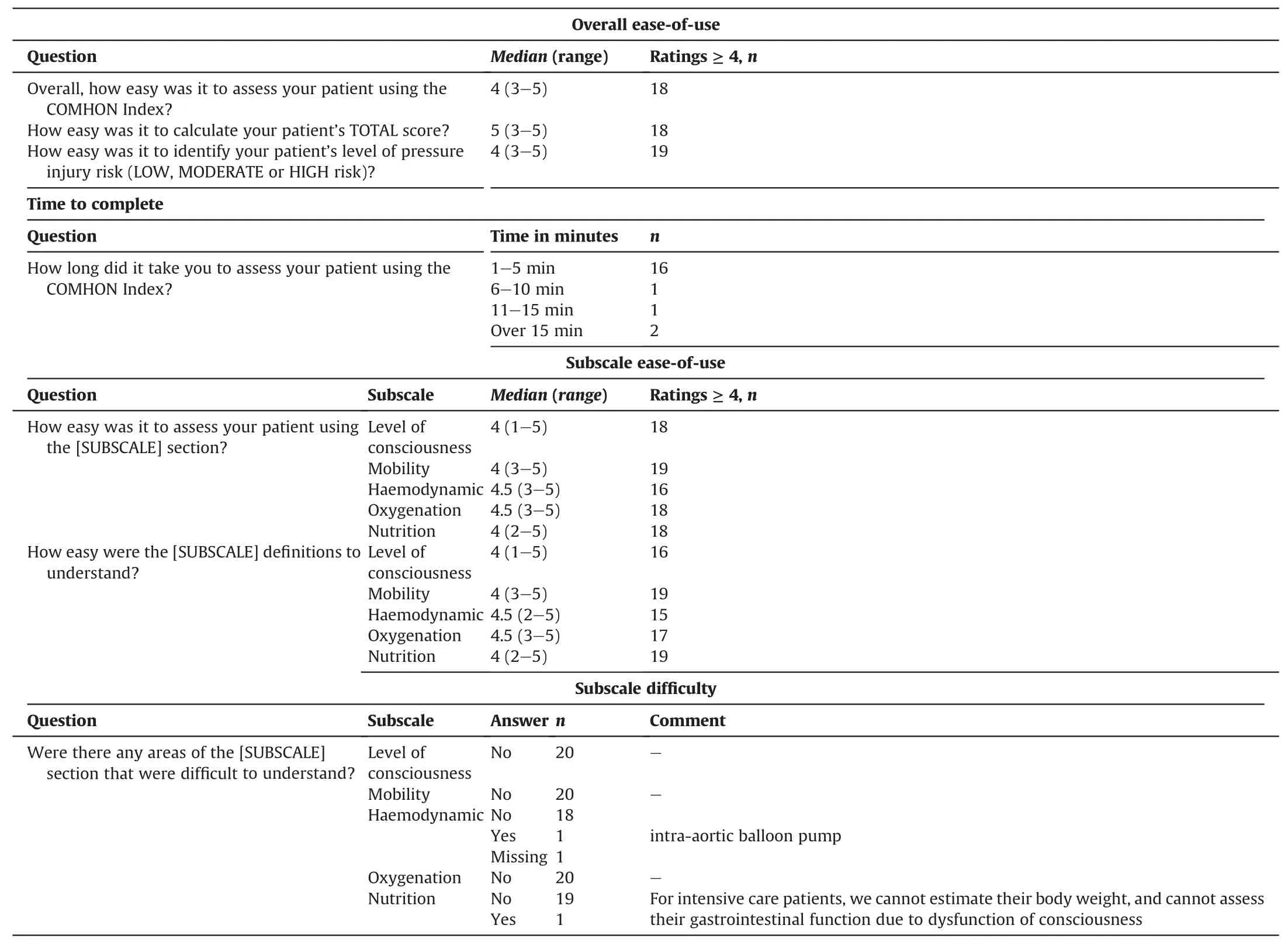

Twenty nurses participated in the pilot study in September 2021.The results are presented in Table 3.

3.4.1.Scoring

The COMHON Index subscale scoring was documented in most cases (16/20, 80%), as was a sum score (19/20, 95%) and risk level(16/20, 80%).Of the 16 assessments with subscale scoring, sum score was totalled incorrectly in three cases.There were 16 assessments which had a sum score and a risk level documented, ofwhich all were correctly converted.However, two were based on incorrectly tallied sum scores, with one converting to a different risk level when the sum score was calculated correctly.

3.4.2.Ease-of-use and understanding

Nurses indicated that overall assessment,sum score calculation and risk level conversion were easy to very easy(≥90%rating 4 and above).The majority (16/20, 80%) found the assessment took ≤5 min to complete.

All subscales had a median of ≥4 for both ease-of-use and easeof-understanding.The level of consciousness subscale had the widest range for both(1-5),but the majority of ratings were ≥4(≥80%).Ease-of-understanding for the haemodynamic subscale was the only item which less than 80%of nurses rated as ≥4(75%),but the median was 4.5.Only two nurses indicated a subscale aspect that was difficult to understand (haemodynamic, nutrition)(Table 3).

Table 3Pilot study results (n =20).

3.5.Final instrument

All subscales achieved medians of ≥4 in piloting, and the translation was finalised.While the COMHON Index did not previously contain directions to circle subscale assessments and document sum score and risk level, these were included on the pilot study assessment form.However, not all nurses documented these.The directions were retained, but enhanced (enlarged, coloured, centered), and added to Version 2.1 of the Spanish, English(Fig.1), and Chinese Mandarin (Fig.2) COMHON Index.

4.Discussion

4.1.Translation approach

A rigorous and replicable approach to instrument translation has been presented.While the lack of consensus on the best approach to instrument [27]and self-report questionnaire [30]translation and adaption remains,it was feasible and appropriate to select and adapt the best approach relative to the research requirements of this translation.For example, we adapted the approach of Cha et al.[26]based on the supporting literature to include two back-translators rather than one.This proved useful to identify errors and establish equivalence, such as where the backtranslators disagreed on a translation in the first iteration.Moreover, it provided additional insight into equivalence; one backtranslator provided more of a clinical interpretation, as opposed to the more literal translation of the other.

4.2.Reporting of instrument translation

There have been calls for more detailed reporting of translations[27]and for cultural adaptions and validation be reported separately to enable adequate and explicit detail[25].Yet,it would seem that the uptake of these recommendations has been limited, with many reports providing only a very brief translation summary against larger psychometric testing or instrument use.Subsequently,translation equivalence and quality cannot be verified,and data obtained using the translated instrument may be inaccurate.Thus, it is imperative that further focus is put on the translation process and its reporting in future research.This report provides an exemplar of the level of detail required to adequately report an instrument translation,while also providing an audit trail.As such,it should be of benefit for future translation studies.

4.3.The Chinese Mandarin COMHON Index

In terms of the instrument itself,a Chinese Mandarin version of the COMHON Index equivalent to the source version has been produced.Of importance is that the pilot study results indicated that nurses found the instrument easy-to-use and understand,particularly given that pilot study participants were unfamiliar with the COMHON Index and received no prior education in its use or meanings.This is in contrast to some concerns voiced for other general PI risk assessment tools, such as ambiguity, and confusing or unclear definitions[38,39].Furthermore, the majority of nurses indicated that COMHON Index assessment was relatively fast to complete(≤5 min),although a few nurses did not fully document subscale assessments, sum scores or risk level.While instructions and sections for documenting these details were amended acrossCOMHON Index language versions(Version 2.1)following piloting,the provision of further education may be beneficial to improve COMHON Index completion and other PI risk assessment and documentation in general.

The cross-cultural generation of an easy-to-use, ICU-specific PI risk assessment tool in a widely used language is of significance.However, prior to use, the instrument requires further rigorous psychometric testing[26,33].In particular,interrater reliability and agreement testing is warranted, given that individuals may be assessed for PI risk by multiple clinicians regularly within clinical practice, and there is a need for risk to be measured consistently among clinicians [16].Subsequently, such testing is already underway.It is also important to note that PI risk assessment itself is not preventative,but that PI preventative interventions must be put in place relative to identified risk.

4.4.Limitations

It has been recommended that back-translators be blinded to the original instrument [29,32,33].However, in this study, one back-translator identified the English instrument online, which may have influenced their translation.Criteria for retaining translations was also not defined until data analysis preparation,potentially introducing some bias.For future translations, implementing steps to address these limitations(i.e.ensuring blinding,a priori criteria specification) would enhance rigour.

Finally, piloting was undertaken in a convenience sample of nurses who were likely monolingual Chinese Mandarin speakers,although some may have been bilingual.Additional testing with bilinguists to compare the target and source language instruments may have provided further insight [27].However, difficulties with the large resourcing requirements of such testing have been acknowledged [27,29]and the sampling undertaken was representative of the intended population and congruent with the intended approach [26].While the pilot study sample size was small (n =20 in one ICU) and generalizability is subsequently limited, it was appropriate for pre-testing an instrument in the context of translation.Beyond translation, any further psychometric testing should be adequately powered.

5.Conclusion

Overall,a Chinese Mandarin version of the COMHON Index has been produced following a rigorous and comprehensive translation approach.This paper provides an exemplar of the level of detail required to adequately report an instrument translation.The translation approach used is replicable and recommended (with modifications based on research requirements) for future healthcare instrument translation.

Fig.1. English COMHON Index Version 2.1.

Given the global high prevalence of PI in ICU,the generation of a Chinese Mandarin ICU-specific PI risk assessment tool is a significant contribution to international PI prevention knowledge and practice.This study has indicated that the instrument is easy-to-use and understand in the population of interest.However, further psychometric testing, particularly interrater reliability and agreement testing,of the translated instrument is required to validate its use in clinical practice.

Fig.2. Chinese Mandarin COMHON Index Version 2.1.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Josephine Lovegrove:Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Resources, Investigation, Data curation,Writing-original draft,Writing-review&editing,Visualisation,Project administration, Funding acquisition.Paul Fulbrook:Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Resources, Writing - review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.Sandra Miles:Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Writing - review & editing, Supervision.Michael Steele:Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation,Investigation,Writing-review&editing,Supervision.Xian-Liang Liu:Validation, Investigation, Resources, Writing - review &editing, Project administration.Lin Zhang:Investigation, Resources,Writing - review & editing, Project administration.Angel Cobos Vargas:Conceptualization, Resources, Writing - review&editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

Funding

This work was supported in part by a PhD scholarship awarded to the first author by The Prince Charles Hospital Foundation[grant number PhD2019-01].The funding source had no role in the study design;in the collection,analysis and interpretation of data;in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Data availability statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge and sincerely thank the following contributors: Associate Professor Frances Lin for her assistance with identifying back-translators; Li Zeng for her efforts in forwardtranslation and data collection; Ying (Maggie) Gao and Yichen(Annie) Wang for their efforts in back-translation; and the pilot study hospital, intensive care unit and the participating nurses for their contribution.

Appendices.Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnss.2022.03.003.

International Journal of Nursing Sciences2022年2期

International Journal of Nursing Sciences2022年2期

- International Journal of Nursing Sciences的其它文章

- Brief Introduction on the Future of Nursing 2020-2030: Charting a Path to Achieve Health Equity

- Subscription of International Journal of Nursing Sciences

- Development and evaluation of a teamwork improvement program

- Recognition of group activities for understanding intraoperative state of surgical team

- Association of operating room costs with head and neck surgical instrumentation optimization

- Editorial Board of International Journal of Nursing Sciences