COVID CONUNDRUM

By Hu Yukun

In his annual Chinese New Year message on January 30, Lee Hsien Loong, Prime Minister of Singapore, talked more about precautions and responsibility than wishes and joy. Amid the unprecedented surge in COVID-19 cases, Mr. Lee was no longer interested in “living with COVID.”

Instead, he told Singaporeans to “wait a little longer” for large gatherings just as families were eager to reunite to celebrate like before. Discouraging as it might sound, the majority ethnic Chinese society could not afford to relax: On the first day of February (also the first day of the Chinese New Year), the number of new COVID-19 cases exceeded 6,000.

And then three days later, more than 10,000 new cases were reported for the second time in a single day in the country with a total population of 5.45 million. Once a highly acclaimed role model for responding to the pandemic and even for ending the “zero COVID” policy with one of the highest vaccination and boost rates in the world, Singapore was then hit hard by the highly transmissible Omicron variant.

The harsh reality meant Singaporeans would have to wait a little longer before fully lifting all COVID restrictions, as would other peoples in the region.

“Wait a Little Longer”?

A year has passed since the military takeover in Myanmar, and the ASEAN country is mired in its most dire economic crisis due to the pandemic and international sanctions. Seemingly less severe in previous total reported numbers of daily new cases, its society andpeople are definitely much more vulnerable to Omicron, with only a third of the population fully vaccinated.

On February 3, the government extended international travel restrictions to the end of February, but the international community has doubts about how long Myanmar can wait and hold out before a “multidimensional humanitarian crisis” breaks out, as the International Labour Organization has forewarned.

Thailand, where international tourism is a major contributor to the economy, continues to struggle. With more daily new cases than both Singapore and Myanmar since the New Year, the Thai government still decided to resume its Test & Go Thailand Pass scheme from February 1, allowing quarantine-free entry for fully vaccinated arrivals from all countries if they apply 60 days in advance and pass a RT-PCR test upon arrival.

The government could not wait to reopen the border to boost tourism, but still remains cautious. The day after the Test & Go scheme resumed, KoosakKookiatkul, chief health officer of Phuket province, one of Thailand’s most popular tourist destinations, mandated arriving tourists to undergo a second RTPCR test five days after arrival.

Other ASEAN countries are following suit, easing restrictions on international travel while maintaining certain regulatory measures. This winter, Omicron seems to be sweeping across the whole region just like the devastating Delta variant did last summer, pushing Southeast Asia to a breaking point, asCNN described. However, strict control measures are unlikely to continue in all these countries because they want to present safety and recovery to the outside world.

If Omicron is “exposing an East-West divide” between Asian countries determined to keep it at bay, as Al Jazeera put it in early January, and many Western governments that accept its spread as inevitable and even a step towards living with the virus, ASEAN countries have reached a crossroads. To “wait a little longer” is not really a final decision, but a makeshift policy intended to balance clamping down on COVID and safely restarting national economies.

More Than One or the Other

The past two years of the COVID-19 pandemic have shown that it is easier to choose than to balance. On February 9, following Denmark and Norway, Sweden lifted almost all the COVID restrictions and ended mass testing, claiming “it’s over,” despite pleas to the contrary from scientists. The announcement was made the day after 66,670 new cases were reported in a single day, and over the next two days, the country witnessed nearly more than 35,000 new cases.

Fully reopening is not such an easy option for Southeast Asia, where vaccination rates vary sharply and population density is much higher than in Scandinavian countries. Still, ASEAN countries have already realized that they can no longer afford strict COVID control measures with the regional economy on edge.

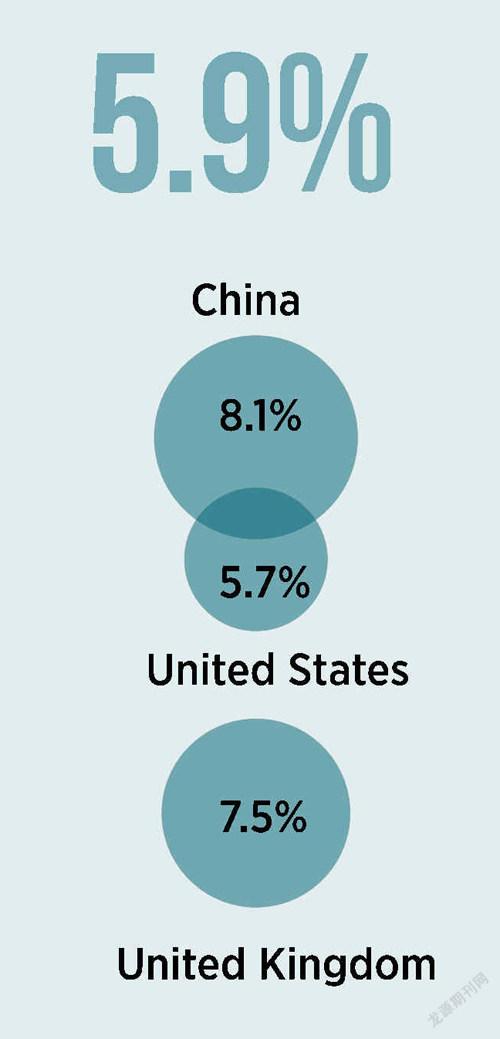

The world economy was expected to show a strong rebound in 2021 and grow 5.9 percent according to the IMF. Among the major economies, China grew 8.1 percent, the United States rebounded by around 5.7 percent, and the United Kingdom soared by record 7.5 percent (highest since Second World War).

The situation has not been as rosy for ASEAN countries. In the IMF’s latest world economic outlook, the overall GDP growth of ASEAN-5 (Malaysia, Singapore, Philippines, Thailand and Indonesia) in 2021 was projected to be much lower than previous projections, at only 2.9 percent. In fact, the actual challenges driving the data are even more severely affecting the whole region.

As tourism-dependent businesses bore the brunt of the pandemic, Thailand’s economy shrank by 6 percent in 2020 and was estimated by the World Bank to rebound by only 1 percent last year. Employment in urban areas including Bangkok dropped by 8 percent, affecting over 50 percent of the population. What’s worse, more than 70 percent of households interviewed by the World Bank experienced income declines, among which 60 percent of low-income families even faced food shortages.

Deutsche Welle’s findings in Myanmar were even more alarming. With construction, garments, tourism, hospitality, and agriculture among the hardest hit sectors, an estimated 25 million people (nearly half of the country’s population) were living in poverty, while “we have started to see an increase of child beggars at traffic lights,” said Min Maung, a local resident from the capital Yangon.

For business owners, the lockdown is more than just control of movement. And the challenges for the year 2022 will not disappear with some eased restrictions.

International sanctions, downsized international aid, and outflow of foreign investment are all pushing Myanmar “to the brink of economic collapse.” Local factory owner Ko Oo expects the coming summer to be tougher, with longer and more frequent blackouts. With limited power capacity and sky-high gasoline prices, his company’s production capacity is already greatly reduced.

Admittedly, uncertainties, lockdowns, supply chain disruptions, and sluggish investment are still baffling ASEAN countries, but opportunities are also emerging alongside challenges in the year ahead.

The World Economic Forum stressed that ASEAN remains an attractive investment destination, with its share of global foreign direct investment (FDI) rising from 11.9 percent in 2019 to 13.7 percent in 2020. Moreover, the value of international project finance in ASEAN has already doubled in five years.

Meanwhile, when the ASEANled Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) Agreement came into force on the first day of 2022 for 10 countries (and for South Korea on February 1), the region showed determination to keep its market open.

ASEAN is on track to become the fourth-largest economy in the world despite uncertainties brought by so many factors including Omicron. The IMF’s GDP growth projection for the region this year is much higher than 2021, while many other major economies will likely see significantly weaker economic performance.

To all ASEAN countries, “wait a little longer” does not need to be a black-or-white choice, but necessary preparations for a challenging yet promising 2022, a year which calls for healthy populations and vibrant societies.