ON THE SHANGHAI COMMUNIQUé AND THE SINO-U.S.RAPPORT

By Ken Hammond

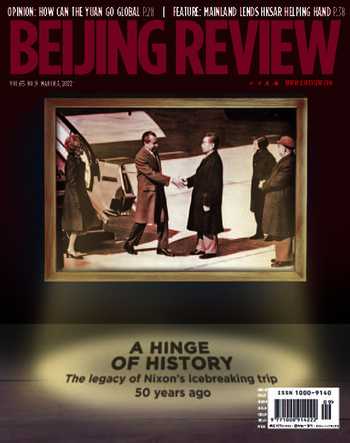

In 1954, representatives of France, Britain, the Soviet Union, the United States and China gathered in Geneva, Switzerland, for a conference on the political and military situation in the Korean Peninsula and in French Indochina. When U.S. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles encountered Chinese Premier and Foreign Minister Zhou Enlai, he refused to shake hands, insulting both Zhou personally and the people of China. Eighteen years later, when U.S. President Richard Nixon arrived in Beijing for his historic visit to China, the first thing he did when he made his way down from Air Force One was to reach out and shake hands with Premier Zhou, symbolically erasing the disrespect which had lingered since Geneva.

Nixon’s trip to China marked a dramatic turning point in the relationship between China and the U.S. American anti-communism had driven the global confrontations of the Cold War since the end of World War II in 1945 and the victory of the Chinese revolution in 1949. Hostility toward China had been a lynchpin of U.S. foreign policy, resulting in the Korean War, the crises in the Taiwan Straits, and eventually the war in Viet Nam. China had initially been seen as simply a subordinate part of the Sovietled “Communist Bloc” in opposition to American claims to be the leaders of the “Free World.” But by the beginning of the 1970s, these attitudes were beginning to shift.

America’s antagonism with the Soviet Union remained the primary concern of policy makers in Washington. As the relationship between China and the Soviet Union deteriorated in the 1960s, culminating in armed clashes on the border between the two countries in 1969, strategic geopolitical thinking was changing both for the Americans and for the Chinese. Nixon hoped to use an opening with China to create a counterweight to the Soviets. Leaders in Beijing were also reappraising China’s position. They came to see American imperialism as a declining force, a decreasing threat to China.

American forces were being defeated in Viet Nam, and political unrest over civil rights and opposition to the Viet Nam War was intensifying the contradiction within the U.S. Mao Zedong came to view an opening with the Americans as giving China a stronger position in relation to the Soviets, and as creating opportunities for China to attract investment from countries like Japan as well as the U.S. itself. Nixon’s 1972 visit brought the two countries together and launched a new era in both their bilateral relationship and general global affairs.

The Shanghai Communiqué was the embodiment of the principles which would underpin U.S.-China relations from that point onward. They included respect for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of both sides, and non-interference in their internal affairs. The U.S. acknowledged that all Chinese, on both sides of the Taiwan Straits, maintain there is but one China and that Taiwan is a part thereof. The question of Taiwan’s status was agreed to be a matter to be resolved by the Chinese people themselves, in their own way and on their own time. These remain four principles according to which both countries should conduct their relationship today.

For many years, the U.S. and China were able to pursue a positive course of mutual benefit. Once formal diplomatic relations were established in 1979, bilateral trade grew rapidly. American investment in China expanded, the U.S. consumer benefited from the availability of Chinese goods, and American businesses were able to make significant profits from their manufacturing activities in China. While they certainly featured differences in terms of social and political systems, both sides viewed the relationship as valuable and treated each other with respect.

Throughout this period from the late 1970s to the beginning of the 21st century, U.S. political and corporate elites also held a vision of the eventual transformation of China from a socialist country to one embracing capitalism and becoming a subordinate component of the American-led global economy. China’s reform and opening up was seen as inevitably leading to the political reconfiguration of the People’s Republic into a Westernstyle “liberal-democratic” system, with the same kind of multi-party electoral politics, dominated by the rich and powerful as they are in the U.S. As China sought to use market mechanisms to develop its productive economy through the reform program, its engagement with the global capitalist system did indeed deepen. China’s joining of the World Trade Organization perhaps best exemplified this. China needed Western capital, technology and operational practices to grow its economy and raise the material quality of life for its 1-billion-strong people. But there was never a plan to move to a fully market-driven economy. The socialist core of the economy, the legal system, and the guiding role of the Communist Party of China (CPC) were meant to ensure that even as private capital helped drive growth, the Party and government would be able to supervise the process and buffer the worst negative effects, which were understood to accompany rapid growth.

Challenges of corruption, inequality and environmental stress emerged over the course of reform. If China was to avoid the fate of political unrest and remain true to its original mission of the revolution, these would all need to be addressed. Yet this was a complex process which required balancing the needs of development with the resolution of the resulting contradictions.

China was able to weather serious crises, including the 1997 Asian financial crisis and the global economic meltdown of 2008, because of its socialist system. And as the positive results of the reform program continued to accumulate, China was able to become less dependent on external factors, less in need of the approval of American or other Western politicians and media pundits.

At the same time, American elites came to realize China was not going to be transformed into a junior partner in the capitalist system, but was going to pursue its own agenda of development, not only domestically but in partnership with other developing countries around the world.

China’s great reform leader Deng Xiaoping in the early 1990s had urged the leaders of the CPC and the government to follow a course of keeping a low profile in world affairs to ensure the smooth development of the reform program. By 2010, this was no longer necessary, and China was becoming more self-confident, and more self-assertive in its role in the world. This led the American leadership, of both political parties, to once again shift their attitude toward China.

In 2011, President Barack Obama announced the “Pivot to Asia,” a redeployment of American military power aimed to contain China. The subsequent Donald Trump administration launched a foolish “trade war” with China. And the current Joe Biden administration has carried on and deepened American hostility toward China. American elites fear losing the dominant place they have held in world affairs for many decades, and they see China’s successes in developing their economy and improving the lives of their people as a threat to the power and privilege the U.S. has enjoyed.

Since Xi Jinping assumed the leading place in the CPC and the Chinese Government in 2012 and 2013, respectively, China has made great strides in addressing the problems of corruption, inequality and environmental issues which face the country. He has given China a new, confident spot in world affairs, seeking to develop relations of mutual benefit with other countries, rather than deferring to the wishes of the Americans.

The combination of American fear and anxiety on the one hand, and China’s reemergence as an important participant in global affairs on the other, has meant that the relationship between them has entered a complicated and dangerous era. The 50th anniversary of the Shanghai Communiqué is a moment when that relationship should return to the path of mutual respect and cooperation embodied in that very document. BR

3729500338223