Exploring the factors influencing nurses' work motivation during the COVID-19 pandemic in King Faisal Hospital in Makkah al-Mukarramah,Saudi Arabia

Albandre Alenezi,Mari Almutairi,Mohammed Saleh Alshmemri,Maram Taher Alghabbashi,Hala Yehia

1Faculty of Nursing, Umm Al-Qura University, Makkah 24382, Saudi Arabia. 2Ministry of health, The Directorate of Health affairs in Northern Province, Arar 91471,Saudi Arabia.

Abstract Background: At this time of severe budgetary constraints and worldwide nursing shortages, the nursing profession is already facing challenges in keeping its professionals motivated to work during the COVID‐19 pandemic. This study explores the factors influencing nurses’ work motivation during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia.Methods: A descriptive quantitative cross‐sectional study was conducted at King Faisal Hospital in Makkah al‐Mukarramah, Saudi Arabia. A convenience sample of 184 nurses participated in the study. An electronic self‐administrative questionnaire in the English language was used to collect data. It comprises two parts: demographic data and the Multidimensional Work Motivation Scale (MWMS) using a 7‐point Likert scale. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and t‐tests were utilized to identify the differences in MWMS scores among participants’ characteristics. Results: The study found that the overall mean score for the MWMS scale accounted for M = 81.32, SD = 18.66, with the highest mean score reported for interjected regulation (M = 20.19, SD = 5.59).Moreover, the results revealed that 62% of the participants attained an average level on the overall MWMS. In addition,the ANOVA and t‐test showed a significant overall effect of the duration of nurses’ work experience, the unit of care, the number of working hours per week and salary on nurses’work motivation during COVID‐19 at P <0.05. Conclusion: The study’s findings suggest that hospital administrators and nursing managers should pay careful attention to nurses’work motivation and related factors to increase nurses’ quality performance, retention and satisfaction.

Keywords:nurses; work satisfaction; motivation; COVID‐19; Saudi Arabia

Background

The world is experiencing a global health crisis that tests healthcare services [1]. The COVID‐19 pandemic seriously affects healthcare workers’ professional and personal lives [2], the healthcare professionals are on the front lines of the COVID‐19 pandemic response and are subject to the risks of being infected with coronavirus [3]. A systematic review and meta‐analysis found that the prevalence of COVID‐19 in healthcare workers was 51.7% (95%CI 34.7–68.2), with a 1.5% mortality rate [4]. In Saudi Arabia,healthcare workers face many physical and mental challenges in caring for COVID‐19 patients, and they are still in danger of catching and spreading the virus [5].

According to the literature, nursing care is highly challenging during the COVID‐19 pandemic, with nurses dealing with a considerable upsurge of tasks and complexity of their job, new procedures and frequent changes in disease management [6].Therefore, healthcare providers require appropriate support to enhance their performance and stay motivated during these difficult times [7].

According to the recent literature, the most reported factors affecting nurses’ work motivation are: nurses’ age, years of experience, educational level, autonomy, administrative positions [8,9], nurses empowerment, work engagement, pay and financial benefits, supervision, promotions, contingent rewards, supportive relationship, the nature of work, and providing adequate COVID‐19 protective equipment at the hospital[6,9–11]

There is an agreement in the literature that work motivation plays a significant role in nurses’ overall satisfaction [12–14], increases nurses’ work performance [10, 11] and heightens good team spirit,patient satisfaction and job attachment [10]. Furthermore, work motivation significantly impacts the nurses’ intention to leave the country and the organization [12].

However, among the reported motivational strategies that were appreciated by healthcare workers and reduced their stress were the rewards provided by the organization’s teamwork, as all health professionals collaborated on the frontlines to overcome COVID‐19[13].

Nurses’ levels of work motivation vary not only according to the working environment of the healthcare organization but also according to the time of change [8]. Therefore, to comprehend the full effects of the COVID‐19 pandemic, it is crucial to explore effective measures to expand the national nursing workforce.Furthermore, it is well known that the shortage of Saudi nurses is among the top priorities of the Saudi Ministry of Health. Thus, this study may illuminate nurses’ intention to leave and turnover during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Furthermore, the present study may allow policymakers to understand working during COVID‐19 on nurses’work motivation in King Faisal Hospital in Makkah al‐Mukarramah,Saudi Arabia, to develop strategies for enhancing nurse motivation,which could result in favourable outcomes for nurses, organizations and patients.

Research Objective

The current study aims to assess work motivation among nurses during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia and to explore the factors contributing to nurses’ work motivation during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia.

Methods

Research design

A quantitative, descriptive, cross‐sectional design was used in this study to explore the factors that influence nurses’ work motivation during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia.

Research setting

The study was conducted at King Faisal Hospital in Makkah al‐Mukarramah, Saudi Arabia. The hospital has a 228‐bed capacity and provides high‐quality health and therapeutic services through 1,180 medical, technical, nursing and administrative staff members. In addition, the hospital has five specialized clinics: ENT, eyes,fractures, EEG and dressing[15].

Research population and sample

Targeted population. The target population consisted of all available nurses working in King Faisal Hospital in Makkah al‐Mukarramah,Saudi Arabia.

Sample size. The total population is 450 nurses working in King Faisal Hospital in Makkah al‐Mukarramah, Saudi Arabia, eligible for the study. The sample size was calculated using an online calculator[16] based on Sarantakos’s Table [17] published table, using this formula by Kerjcie and Morgan [18]:

According to sample size calculation with a confidence level of 95%and a margin of error of 5%, 208 respondents were needed.

Sampling method. The current study used convenience sampling techniques to select the most beneficial research participants. Aconvenience sampleis a group of participants available for a study[19].

Instrument of data collection

An electronic self‐administrative questionnaire in the English language was used in this study. It comprised two parts; the first was a demographics questionnaire developed by the researchers to collect nurses’ personal and professional characteristics, presented as closed‐ended questions.

The second part included the Multidimensional Work Motivation Scale (MWMS) developed by Gagné et al. [20]; this tool was adopted and used after obtaining permission from the author. The aim of using this tool was to fully capture nurses’ motives to perform their job during COVID‐19. The MWMS is a 7‐point Likert scale with six subscales: Amotivation, Extrinsic Regulation–Social, Extrinsic Regulation–Material, Introjected Regulation, Identified Regulation and Intrinsic Motivation. Each of them contains three items. Total scale items were 19 scored out of 7, starting from 1 = not at all; 2 =very little; 3 = a little; 4 = moderately; 5 = strongly; 6 = very strongly to 7= completely.

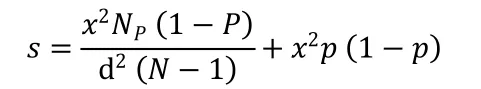

The Cronbach’s alpha for the MWMS dimensions ranged from 0.83 to 0.93. The total reliability statistic for the current study was 0.90(See Table 1).

Table 1 Reliability statistics

Data analysis methods

Obtained data were coded, entered and analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 25 for Windows. The nurses’ personal and professional characteristics and the scores of MWMS were presented using descriptive statistics that include frequencies, percentages, means and standard deviations. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and t‐tests were utilized to identify the differences in MWMS scores among participants’ characteristics. Values ofP<0.05 were considered significant. Microsoft Word and Excel were used to generate graphs and tables.

Ethical and administrative considerations

Data were collected using an electronic self‐administrative questionnaire, and ethical considerations from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) and Ministry of Health (MOH) were obtained(IRB number: H‐02‐K‐076‐0322‐678). To ensure the recommended sample size, the hospital’s nurse manager was approached as a central contact point for nurses, and the link to the electronic questionnaire was published to 208 nurses by the researchers. During the data collection procedure, the researchers maintained the following ethical standards for collecting the data. Participants were informed of the study’s objectives and voluntary participation. They were also informed that completing the questionnaire was considered consent. The researchers ensured the anonymity of the participants and confidentiality.

Results

Personal and Professional Characteristics of study participants

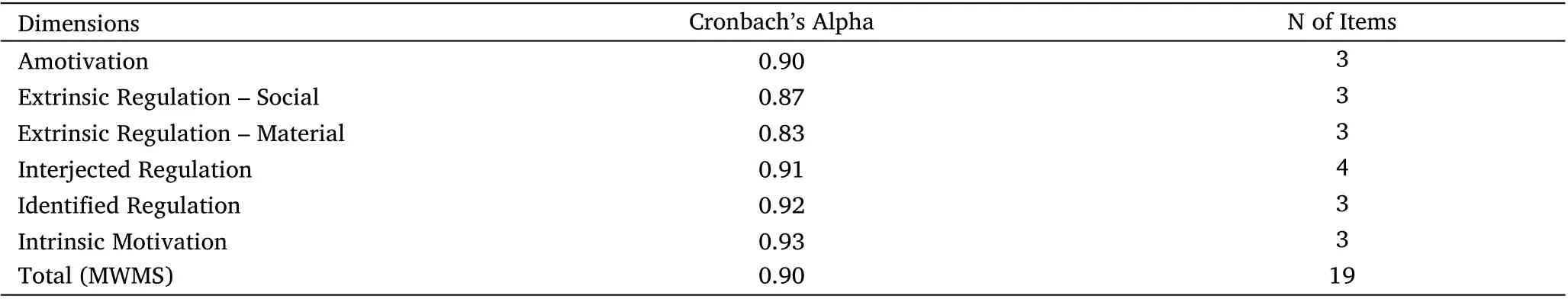

A total convenience sample of 208 nurses was recruited. In general,184 nurses (88.4%) fully completed the survey. Of the 184 nurses participating in the study, 67.9% were females, and 32.1% were males. The demographics of the study participants are presented in Figure 1.

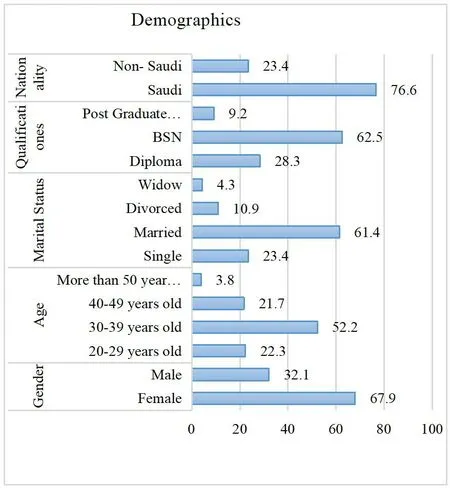

Moreover, 39.1% of nurses had more than ten years of experience.More than one‐third (33.2%) of participants were working in general wards, 29.9% of the nurses were in the critical area, 23.9% were in out patient department (OPD) and others, and 13% were in the nursing office. More than half (66.8%) of the participants worked less than 50 hours per week. Almost half (40.2%) of nurses worked in their respective hospitals between one and five years. (See Figure 2).

Figure 1 Participants’ demographics (N = 184)

Figure 2 Participants’personal characteristics (N = 184)

Responses reflecting levels of nurses’motivation

To facilitate the interpretation and comparisons of the nurses’responses to the items reflecting their level of work motivation, the dimensions of work motivation were evaluated based on three levels:weak, average, and high. First, each participant calculated and converted the total score into a percentage. Then, the participants who had a total score of less than 50% were considered at a low level, the participants who had a total score of 50% to 75% were considered at an average level, and participants who had a total score of more than 75% were considered at a high level in a specific dimension of MWMS.

The results found that the overall mean score for the MWMS scale accounted for M = 81.32, SD = 18.66, with the highest mean score reported for interjected regulation (M = 20.19, SD = 5.59) and the lowest score for amotivation (M = 6.58, SD = 3.69). For the amotivation dimension, most (85.9%) nurses were at a weak level,42.4% were at an average level of Extrinsic Regulation – Social, 37%of participants had a high level of Extrinsic Regulation–Material,55.4% were at a high level of Interjected Regulation, 60.9% were at a high level of Identified Regulation, and 37% of the sample were at a high level of Intrinsic Motivation. However, 62% of the participants received an average level on the overall MWMS

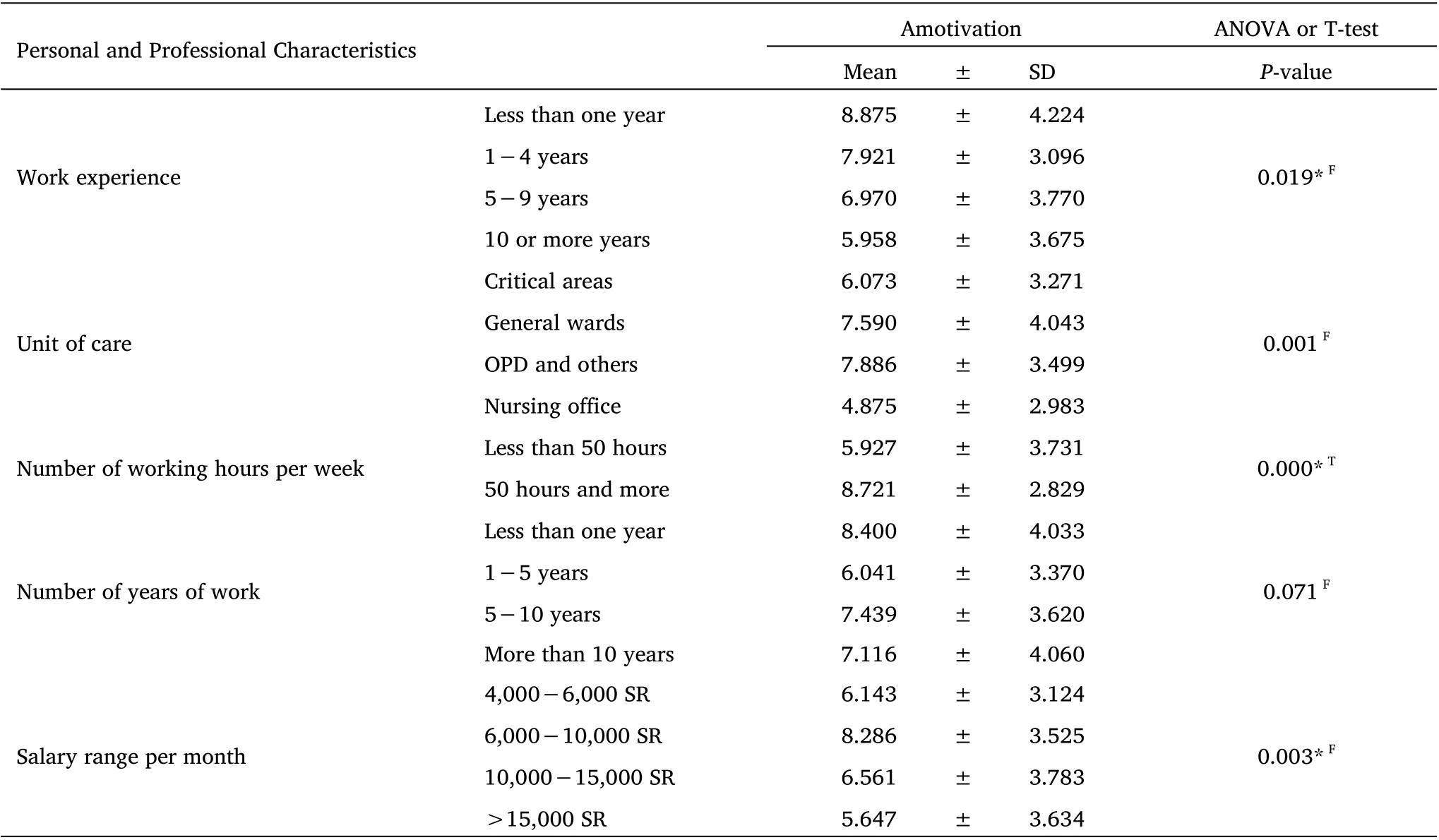

The ANOVA and t‐test showed a significant overall effect of the duration of nurses’ work experience, the unit of care, the number of working hours per week and salary on the mean of amotivation scores. The results demonstrated that the amotivation score was significantly higher among nurses who had worked in their respective hospitals for less than one year (M ± SD = 8.87 ± 4.22), nurses working in OPD and other units of care (M ± SD = 7.88 ± 3.49)and nurses who had monthly salaries ranging between 6,000-10,000 SR (M ± SD = 8.28 ± 3.52). Regarding the number of weekly working hours, the results of the t‐test indicated that nurses working more than 50 hours a week obtained a significantly higher score on amotivation (M ± SD = 8.721 ± 2.829) than nurses working less than 50 hours per week (M ± SD = 5.92 ± 3.73), (P=0.000) (See Table 2).

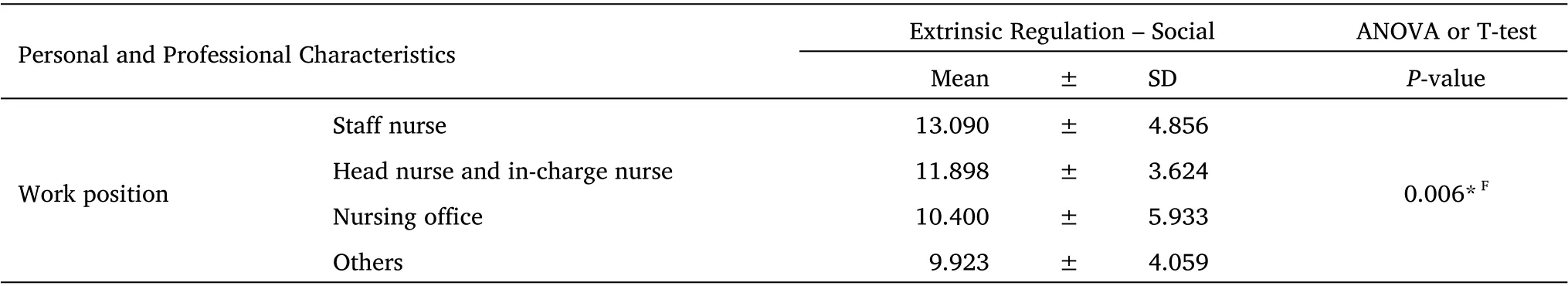

Concerning the nurses’ perceptions of the motivational dimension Extrinsic Regulation – Social according to their demographic characteristics, it was found that there were statistically significant differences among nurses according to their work positions. The mean score of Extrinsic Regulation – Social was higher among staff nurses (M ± SD = 13.09 ± 4.85), whereas the lowest reported score was among other nursing positions (M ± SD = 9.92 ± 4.05), (P=0.006) (see Table 3).

Table 2 Amotivation subscale and demographic data (N = 184)

Table 3 Extrinsic Regulation – Social subscale and demographic data (N = 184)

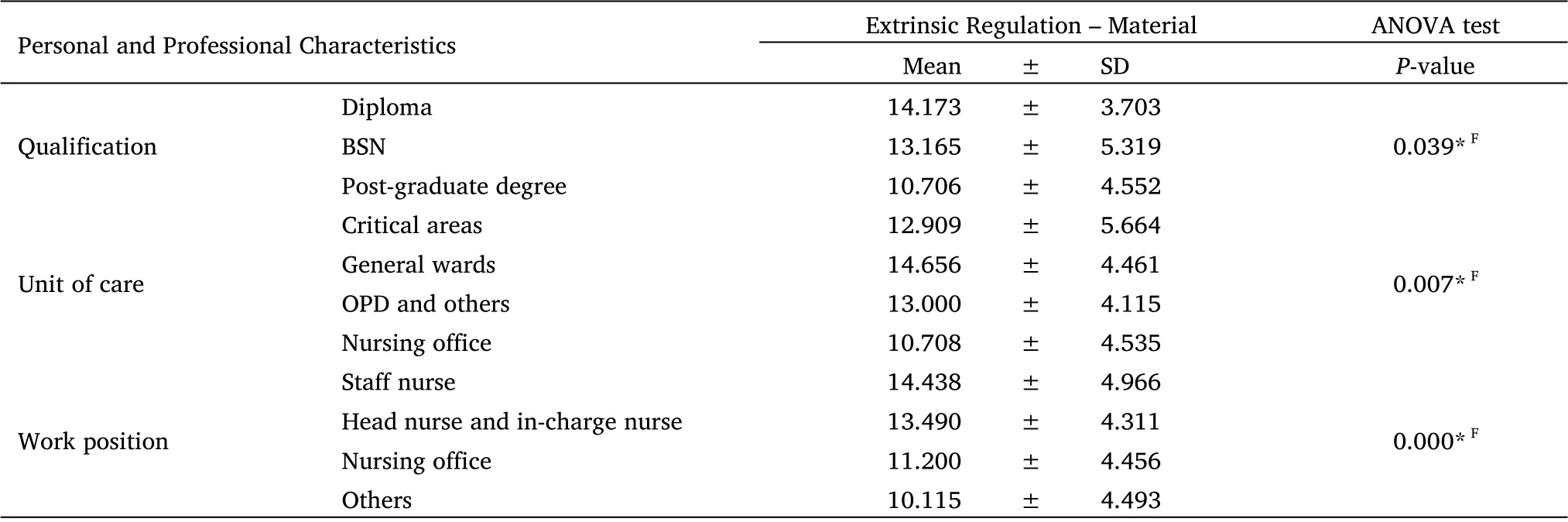

Moreover, the mean score of extrinsic regulation–material was significantly higher among nurses who had diplomas (M ± SD =14.17 ± 3.70) at p= 0.039, nurses who worked in the general ward(M ± SD= 14.65 ± 4.46) atP= 0.007 and, nurses who were working in other nursing positions (M ± SD = 10.11 ± 4.49) atP=0.000(see Table 4).

The results indicated that nurses aged more than 50 years old were significantly less motivated with Interjected Regulation (M ± SD =14.42 ± 7.59). In addition, the findings demonstrated that nurses who work less than 50 hours per week reported higher scores for the motivational dimension Interjected Regulation (M ± SD = 21.33 ±5.10) than the nurses who work more than 50 hours per week (M ±SD = 17.90 ± 5.87), (P= 0.000). Finally, regarding monthly salary,the ANOVA revealed a significant effect. The results demonstrated that nurses who gained more than 15,000 SR were significantly more motivated with Interjected Regulation (M ± SD = 22.76 ± 4.49)(see Table 5).

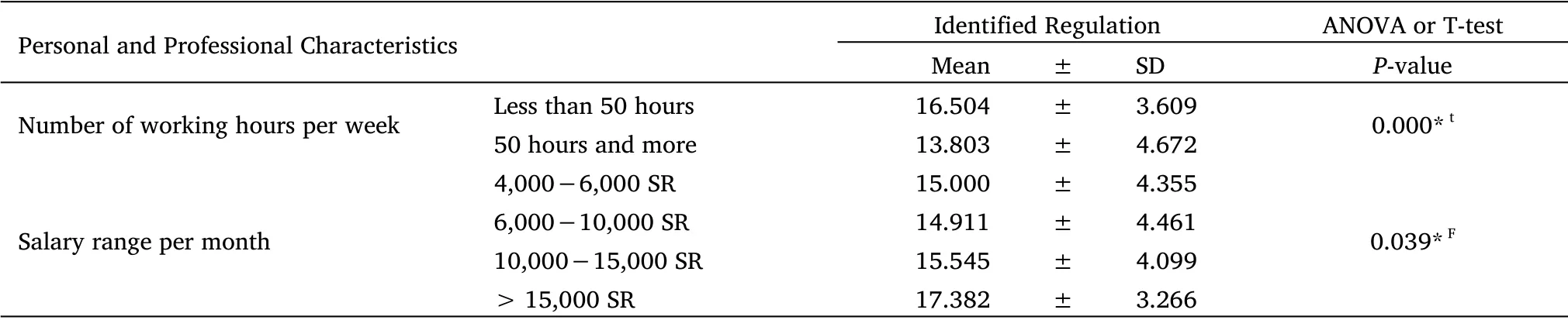

The study results found significant differences among nurses’ scores for the Identified Regulation regarding weekly working hours and nurses’ monthly salary. The findings revealed that nurses who worked less than 50 hours per week reported higher scores (M ± SD= 16.504 ± 3.609), and nurses who gained more than 15,000 SR were significantly more motivated with the Identified Regulation (M±SD = 17.382 ± 3.266)(see Table 6).

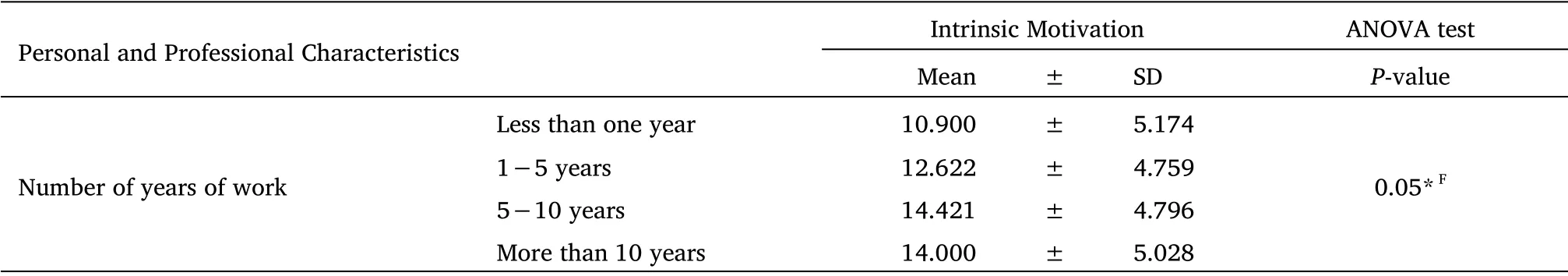

Concerning the nurses’ perceptions of the motivational dimension of Intrinsic Motivation according to their demographic characteristics; it was found that the mean intrinsic motivation score was higher among nurses with 5–10 years of nursing experience (M±SD = 14.421 ± 4.796)(see Table7).

Table 4 Extrinsic Regulation –Material subscale and demographic data(N = 184)

Table 5 Interjected Regulation subscale and demographic data (N = 184)

Table 6 Identified Regulation subscale and demographic data(N = 184)

Table 7 ANOVA and T-test between Intrinsic Motivation subscale and demographic data (N =184)

Discussion

Work motivation is essential for healthcare workforce management since it affects performance, employee retention, and job satisfaction[21]. This study’s participants were mostly females in their thirties.The male‐to‐female ratio in nursing is still low, and females dominate the profession. The current study’s findings align with a growing trend among healthcare organizations to hire young nurses for tasks requiring physical ability [21]. Similarly, Alhakami and Baker [22]discuss that males in the nursing workforce have numerous opportunities to be pioneers in such a female role. However, they are treated as a trivial workforce compared to females.

During the study, nurses had relatively long years of experience working in their respective hospitals, possibly due to the higher professional requirements in Saudi Arabian healthcare organizations.As a result, nurses’ work motivation varies according to the working environment and the time of change[8].

To discuss the first objective of the current study, based on the findings obtained, most nurses had general low‐to‐average scores in their work motivation level (scored ≤75).

Moreover, five studies reported that the current COVID‐19 pandemic had affected nurses’ work motivations. In line with the present study’s findings, Turkish research by Boran et al. [23] found decreased motivation to work during the pandemic in 89% of the physicians and 88.7% of the nurses. In addition, in Indonesia,Windarwati and his colleagues [13] found that most healthcare workers faced work disruption due to COVID‐19. However, they are committed to working as their duty to fulfil their ethical obligations.Unlike previous findings, Sperling [24] found that nurses were highly motivated to work during the pandemic and were mainly influenced by their commitment to treating patients. Similarly, researchers in the USA [25] and Iran [10] found that nurses were highly motivated to work during pandemics.

The study also highlighted identified introjected and identified regulations as essential aspects. More than half of the sample was motivated by introjected and identified regulations. Motivation comes from satisfying others’ needs, such as performing to avoid guilt or a psychological need to succeed [20]. Furthermore, the current study’s results revealed that about half of nurses have average and high levels of work motivation regarding extrinsic regulations (social and material).

These results indicated that the nurses were motivated to work during the pandemic because they felt they satisfied the demands of others, the need to align with personal and job values and to be rewarded. In the same context, in the USA [26] and China [26], the studies found that participants believed they were motivated to continue working by a sense of duty and responsibility; they stated that they believed they had a social and professional obligation to continue working during pandemics. Similarly, in Indonesia,Windarwati and his colleagues [13] stated that despite the work disruption due to the outbreak of COVID‐19 faced by nurses, they committed to working as their duty to fulfil their ethical obligations.In line with the previous findings, in Spain, Ruiz‐Fernández et al.[27] stated that alleviating suffering and social recognition has been the reviving elements of motivation in nurses. Li et al. [28]concluded that the COVID‐19 outbreak enhances professional identity. Similarly, Fernandez et al. [29] stated that nurses’ sense of responsibility, commitment to patient care, personal sacrifice and professional collegiality increased during a pandemic.

In the current study, nurses connected deeply with their intrinsic motivation for providing care despite the unique conditions brought about by this pandemic. The current study found that more than one‐third of participants had a high level of intrinsic motivation. Even with the low contribution of intrinsic motivation to the overall motivation level, it is still essential. Matching this clarification, Abu Yahya et al. [21] found that intrinsic motivation is the factor that has the most negligible impact on nurses’ total motivation.

The rationale for these results could be related to the fact that nursing is less enjoyable, attractive and exciting than other professions because it demands a great deal of dedication and self‐sacrifice. Conversely, nurses directly dealing with COVID‐19 need to adjust to their changing work environments and find ways to overcome these stressful situations [30]. Therefore, nursing care is highly challenging during the COVID‐19 pandemic, with nurses dealing with a considerable upsurge in job complexity, new procedures and frequent changes in disease management [6].

To discuss the second objective in the current study, nurses’personal and professional characteristics do not seem to be potential predictors of work motivation. However, this study’s findings show a significant difference in amotivation, and intrinsic motivation among nurses with varying years of experience.

The study found that less‐experienced nurses are disengaged,helpless, and easily quit when performing activities. In addition,inexperienced nurses found their work uninteresting and unfulfilling,unlike nurses with long years of experience. This issue may be caused by nurse maturation, leading to differences in work motivations,competencies, ambitions, requirements, and values. Similarly, a review by Baljoon et al. [8] found that nurses’ work motivation is affected by their years of experience. Moreover, Shan et al. [31]found that nurses with less experience had the worst self‐reported performance. Inconsistent with previous findings from South Africa,Breed et al. [9] found that years of experience do not affect nurses’motivation.

In the current study, outpatient department and general ward nurses had significantly higher amotivation and extrinsic regulation scores than inpatient nurses. These results showed that nurses in high‐risk medical units were less motivated to work and were driven by financial incentives. These units focus on direct patient care, making nurses vulnerable to COVID‐19, which causes burnout and mental breaks. In the same context, in Spain, according to Ruiz‐Fernández et al. [27], health professionals working in specific COVID‐19 units and emergency units had higher compassion fatigue and burnout.

The study found that nurses’ monthly salary affected their motivation. Low‐paid nurses were less motivated. However, during the COVID‐19 pandemic, nurses felt disengaged and incompetent at work and quit quickly. On the other hand, high‐paid nurses are more motivated to help others and avoid guilt or a psychological need to succeed. Similarly, according to the recent literature, the most reported factors that affect work motivation among nurses are organizational factors, including pay and financial benefits,promotions, contingent rewards, communication and the nature of work [32, 9, 25, 13]. Furthermore, Ayalew et al. [33] reported an interesting finding that salary was associated with overall job satisfaction, indicating that nurses’ dissatisfaction with their pay is a significant source of a lack of motivation.

The present study revealed that nurses’ work positions affect nurses’ extrinsic regulation – social and material motivation. There were statically significant differences in the extrinsic regulation –social and material motivation means among nurses with varying work positions. It was found that the mean scores of extrinsic regulations–social and temporal motivation - were higher among staff nurses. In the same context, Baljoon et al. [32] reported in their review that nurses in leadership positions were more motivated than nurses’staff.

In the current study, the results indicated that the nurses’qualifications significantly affected work motivation. However, a significant difference in nurses’ work motivation based on educational qualification was reported in the earlier study by Baljoon et al. [32]. In results inconsistent with previous findings, Breed et al.[9] found that nurses’ qualifications do not serve as factors that affect work motivation in their study on nurse leaders.

The factors influencing nurses’ work motivation during the COVID‐19 pandemic have not been investigated adequately in Arab countries or Saudi Arabia. Based on the current literature, this study was the first to explore the factors influencing nurses’ work motivation during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia, specifically in Makkah al‐Mukarramah.

Research Limitations

The researcher faced limitations in reaching an adequate number of participants due to the selection of the mode of survey distribution.Many nurses could not participate because they were busy with their active jobs. Although the respondents were given specific instructions before completing the survey, however, there may be a chance that they have not answered all the questions honestly. Likewise, the recruitment methods of the WhatsApp groups were unproductive;this also may have led to a low response rate and response bias.Furthermore, because this study used a cross‐sectional design,generalizations of findings should be made with caution. Future research should be duplicated in a larger sample size to allow broader generalization, and they should use more advanced correlation techniques, such as multivariate and regression analysis.

Conclusion and Recommendation

Recruiting, motivating, and retaining employees is essential for any health organization, especially during the COVID‐19 epidemic. In this study, nurses reported low‐to‐average motivation during COVID‐19 and nurses’ work experience, work units, salary, nursing position,and nursing qualification affected nurses’ work motivation the most.Since there are multiple healthcare systems, nurse job motivation and influencing factors vary by organization.

Overall, the study’s findings suggest that hospital administrators and nursing managers should pay careful attention to the nurses’work motivation and related factors to increase nurses’ quality performance, retention and satisfaction. Fuelling nurses’ confidence that they must work under pressure to fulfil ethical obligations will lead to costly behaviour. Increasing nurses’ work motivation is needed. Intervention initiatives that reduce controlled motivation at the beginning of a career are also encouraged. An example of intervention for nurse managers would be to assess the skills of their new nurses and offer orientation and mentoring programmes to support their internal motivation.

Improving nurses’ motivation involves giving them challenging and unusual tasks to assess their expertise, recognize their competencies and skills, and expand their internal abilities. Furthermore, financial rewards encourage nurses to work harder and integrate their professional and personal values. According to the study’s results,efforts to improve work motivation may be an effective strategy for increasing the recruitment of Saudi nurses. As a result, nursing management should try to comprehend the hospital’s environment and its influences to provide nurses with a healthy, productive, and motivated practice environment.

Nursing Communications2022年13期

Nursing Communications2022年13期

- Nursing Communications的其它文章

- Delphi and Analytic hierarchy process for the construction of a risk assessment index system for post-stroke shoulder-hand syndrome

- A review of obstacles and facilitating factors of implementing Clinical Ladder Programs in nursing

- Spiritual health, empathy ability and their relationships with spiritual care perceptions among nursing students in China:A cross-sectional correlational study

- Qualitative study on influencing factors of refusal of gastric tube placement in stroke patients with dysphagia

- The influence of professional identity and ageism on turnover intention in nursing homes: a cross-sectional study from suzhou, China

- The relationship of family separation and nutrition status among under-five children: a cross-sectional study in Panti Public Health Center, Jember Regency of East Java, Indonesia