Establishing and reporting content validity evidence of periodic objective treatment review and nursing evaluation

Daniel Varghese,David Timmons

1National Forensic Mental Health Service,Central Mental Hospital,Dublin D14 W0V6,Ireland.

Abstract Objective: To design, create and validate an evaluation tool to measure progress of the patient within the national forensic mental health service. Methods: A methodological study with two sequential stages was used for this study. Stage 1 was the instrument development; stage 2 was expert judgment and each for these stages had 3 steps. Results:The 28-item questionnaire was submitted to 20 experts. Both descriptive and quantitative analysis were undertaken. The descriptive analysis included item ambiguity, median and percentage agreement. The quantitative method included a content validity index, content validity ratio and content validity coefficient. The acceptable values for item ambiguity,median and percentage agreement,content validity index,content validity ratio and content validity coefficient were a range of 3 or more between scores,median of 2.75 and above, 80 percent criterion,0.79,0.75 and 0.79 respectively.Conclusion:The 28-item tool met all the set criteria for content validity meeting the parameters established in the literature.

Keywords:forensic mental health nursing; nursing notes; portrane tool

Background

In Ireland, forensic mental health service is provided at the National Forensic Mental Health Service (NFMHS), currently located in Dundrum. The service is to move to a new purpose-built setting at Portrane in the near future bringing up the capacity to 170 from the current 99 inpatients. NFMHS caters to patients admitted under the criminal law insanity act and mental health act. The role of a forensic mental health nurse has expanded beyond the inpatient setting to include prison in-reach services and community service in the last 30 years. The nursing roles in the forensic mental health setting are evolving and play a vital role within a multidisciplinary team.

The unique nature of nursing interventions and notes is that they are completed 24×7 in a chronological manner and evaluated against the most recent intervention. Therefore, a robust data capturing and evaluating mechanism is very important in all health care settings,especially within a forensic mental health setting. One of the drivers for such a demand is the length of stay of patients within a forensic mental health service which averages six years within NFMHS. Seven pillars of care provide a framework for care pathways within NFMHS.Individual needs are grouped under these pillars for which therapeutic goals are formulated, and specific goal-based intervention is formulated and delivered over an agreed time frame. The patient’s progress is evaluated by reviewing the patient’s notes weekly at the multidisciplinary meetings and other clinical meetings such as a case conference. The mainstay of such review remains the qualitative,narrative notes. However, quantifiable data is seen to be more effective in periodic evaluation compared to qualitative data.

NFMHS is currently implementing an electronic health record.Working groups of staff nurses, supervisors, and health care assistants meet on a regular basis to learn about the new system’s nursing requirements. One of the most commonly mentioned things is the requirement for a measurable assessment document. The system should be reliable and track the patient’s progress through the seven pillars of care. Quantifiable measurements should be dynamic and simple to implement. The evaluation should take place once a week before a multidisciplinary team meeting. The results of such an examination will be used to inform the a multi-disciplinary team(MDT) meeting. Trends, graphs, and patterns derived from quantitative data will also be useful in goal planning and forecasting patients’ journeys. Periodic Objective Treatment Review and Nursing Evaluation (PORTRANE) is developed to provide nurses within NFMHS with a tool for quantifying patient progress.This progress can be measured across the clusters, i.e. acute, medium, rehabilitative,and under the seven pillars of care.

Content validity estimation for the proposed periodic objective treatment review and nursing evaluation

Methodology overview

Reliable and valid instruments are necessary for researchers to develop and refine complex constructs [1]. A valid instrument measures what it is supposed to measure [2]. Moreover, a valid tool helps researchers interpret variables and their relationships more theoretically [3]. Therefore, any researcher aiming to develop a new instrument should be aiming to develop a valid instrument.

There are three types of validity – content, criterion and construct validity. During an instrument construction, both criterion and construct validity are dependent on the content validity,and therefore more attention is given to the content validity. In instrument development, psychometric testing is needed, and the first step is to conduct content validity. Content validity is a critical step in developing a new measurement scale, and it represents a beginning mechanism for linking abstract concepts with observable and measurable indicators [4]. When an instrument is constructed,psychometric testing is needed, and the first step is to study content validity [5].

A two-stage process(see Figure 1) was used to establish the content validity of the tool. The purpose of this study is to establish the content validity of an instrument to document a patient’s progress with forensic mental health service using a rigorous development and judgment-quantification process.

The initial part of the content validity research was the construction of the instrument.A panel of specialists then evaluated the scale using descriptive and quantitative analyses to produce content validity evidence. This was the second step of the content validity investigation.

Figure 1 The flowchart of the content validity process

Discussion

Stage 1–Instrument development

The tool was developed by following three sequential steps: A) Item identification, B) Item generation, and C) Item construction.

Step 1: Item identification. A quantitative approach is regarded as standard in evaluating patient progress. Many standard evaluative tools are available for nurses across all specialities. The nature and content of the nursing evaluative tool depend on the organization’s nature of services. The availability of standardized care evaluation documents improves nursing care and helps benchmark care quality with other services. The evaluative tools can often be a legal or regulatory requirement to improve patient care. Within the forensic mental health service,care evaluation is underpinned by the Model of care, MHC (Mental Health Commission) requirements, Hospital policies and broader HSE (health service executive) reporting requirements. Model of care provides a framework for active treatment goals, interventions and evaluations.

Moreover, the Model of care underpins the seven pillars of care approach in providing holistic care to patients. Every intervention provided within NFMHS can be linked to one of the seven pillars.Therefore,it was concluded that the tool should be stratified under the seven pillars of care.

Working groups were conducted within nursing to understand the nursing documentation and feedback structure within NFMHS.Inefficiencies around quantitative feedback on patient progress emerged as a strong theme/necessity in these working groups. The staff highlighted the inadequacies of linking the daily work and progress made by the patient in the forensic setting to the pillars of care. Moreover, the hospital currently uses Integrated care pathway progress notes to document daily documentation by all disciplines.Such a system generates descriptive composite data across all disciplines in one place; however, it is challenging to use this data to evaluate patient progress across the seven pillars of care stipulated by the Model of care.

The nursing staff suggested that patient progress evaluation needs to be categorized under the seven pillars of care and linked to the individual care plan. Progress evaluation based on agreed goals can lead to increased quality of care.

Step 2: Item generation. Two approaches can be used for Item generation: first, adapting items from an existing scale and, secondly,utilizing a qualitative approach [6]. Utilizing a robust review of literature is now suggested along with the qualitative stage[7].In this study, working groups (focus groups) were used for qualitative approach. It is suggested that generation of instrument items should be done by involving members of population of interest to represent the need [6]. However, this approach, would warrant the tool’s administration by a large number of professional experts. Such an exercise could potentially impact the quantity and quality of the professional experts. Hence, a decision was taken to incorporate published documents and literature to inform the item generation of the tool. In this study, the Model of care document, Hospital policies,Dundrum toolkit, DRILL (Dundrum restriction and intrusion liberty ladders), and Information generated from the working group was considered to create the main themes under each pillar of care.

Step 3: Item Construction. Further to Item generation, these items were organized under the seven pillars of care on the tool. Each item was defined, and these definitions/explanation acts as a reference for the nurse completing the tool (Table 1). Four items were identified under each pillar,and each item was progressively scaled from a score of 1 to 4, with 1 being the best score and 4 the worst score for the item. To analyze validity, the professional experts were asked if they felt the item was necessary and assessed the degree to which an item fits with the respective pillar.

Table 1 The items generated and their sources

Table 1 The items generated and their sources (Continued)

As evidenced in Dykema et al. [8] and Belotto [9] studies, neutral responses were avoided, and a four-point scale was used. Allocated space was provided for the professional experts to add any suggestions and comments on how to improve the item and its subscales [10].Such suggestions and comments aimed to address the requirement that the item adequately represented each pillar. The professional experts had a total of 28 items and 112 subscales in total to review.At the bottom of the form, additional space was also provided for any additional comments on how the items could be revised. The experts had to review 140 items.

Stage 2–Expert judgment

This stage aimed to ascertain the extent to which the items developed represented the pillars they were developed for.

Both the relevance and the representativeness of the items were used in the assessment. Content validity of the tool was directly proportional to the relevance and representativeness rating.

A description of the process conducted to obtain the professional expert judgment of the items developed for the tool is presented below.

● Step 1: Solicit expert participation.

● Step 2: A description of the experts (content reviewers), who participated in the study.

● Step 3: The analysis of expert ratings.

Step 1: Solicit expert participation. Experts who consented to participate were provided with a package containing: a) a covering information letter and b) a content rating form. Participants were given two weeks to complete the form and send it back to the researcher. A brief introduction to the tool, its evolution and its need was included in the covering information. The population completing the survey and an overview of the task involved were also included in the covering information.

The procedure and purpose of the study were explained to each participant, and assured that their data would be kept confidential.The participants were also given the freedom to discontinue at any time by returning the content form to the researcher.They were asked to analyze the content by checking the degree of fit of each domain to its description [11].

Step 2: Selection of the participants. The number of participants available to participate in this study was limited to NFMHS,Ireland,as the instrument was solely based on the Model of care framework incorporating the seven pillars of care. Criteria set out by Aravamudhan and Krishnaveni [11] were used in this study to select expert participants. In the selection of the expert participants, the following were taken into consideration:

a) experienced nursing managers with over ten years of experience in forensic mental health;

b) experienced nurses with over two years of experience in forensic mental health, experienced nursing clinicians with over ten years of experience in forensic mental health and delivering specific therapies.

A convenience sampling method was utilized to find expert practitioners. Care was taken to include a minimum of two participants for each grade of nursing. The grades included in the study were: staff nurses, clinical nurse manager 1, clinical nurse manager 2, assistant director of nursing, Nurse Pillar Clinicians, ANPs(advanced nurse practitioner).

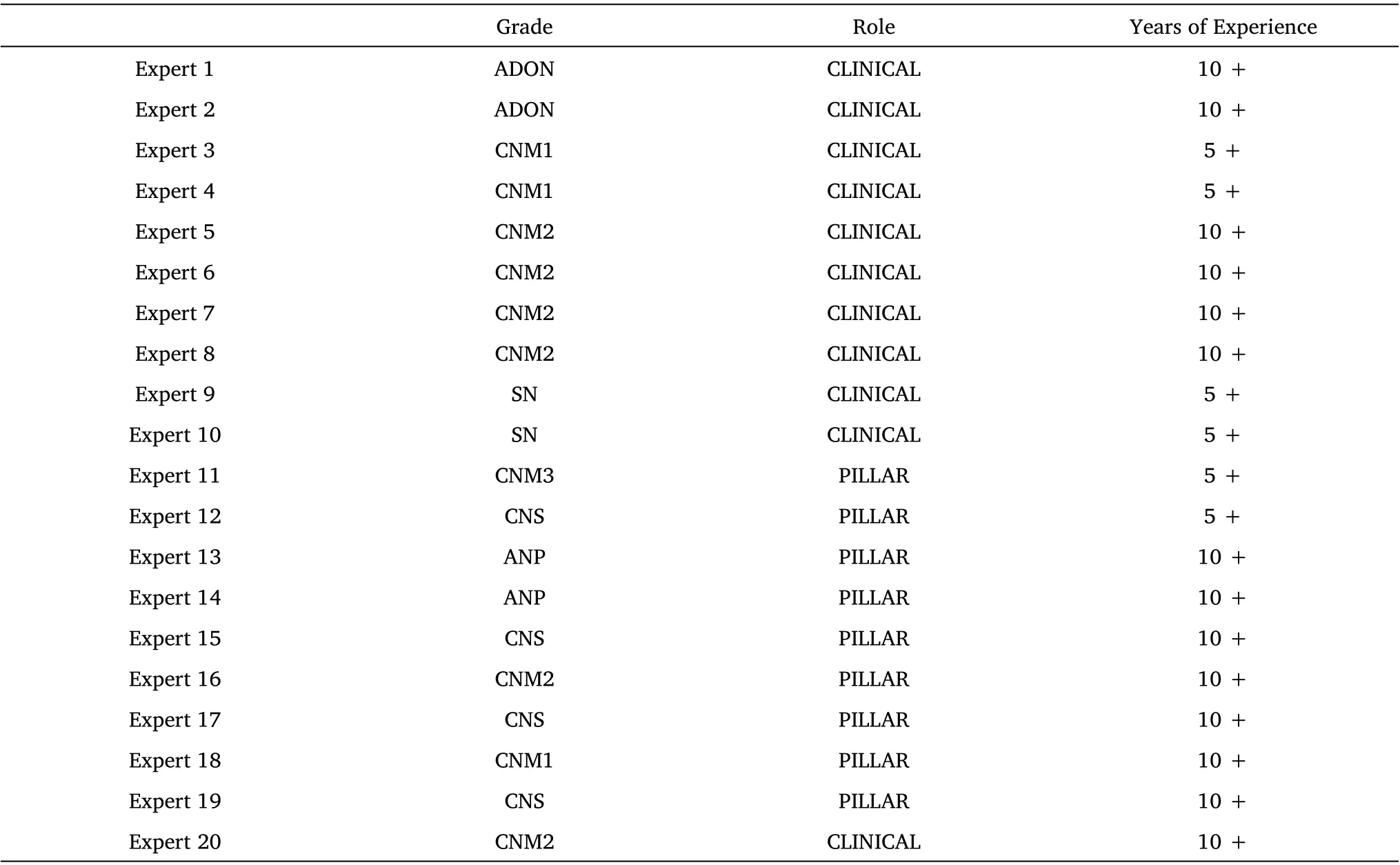

Table 2 shows the years of experience of the professional experts.Except for staff nurses and CNM1 (clinical nurse manager 1), all professional clinical experts had more than ten years of experience.Pillar experts were an exception to the criteria;however,their value as an expert is enhanced by their current role in delivering quality care for the pillar.

Step 3:Analysis of expert ratings.This study employed a descriptive and quantitative analysis to obtain professional expert judgment about the tool. Due to the time and cost-efficiency of the quantitative and descriptive analysis, qualitative analysis was not conducted in the study. The resource implications also informed this approach of a qualitative study.As evidenced in the study by Saptono et al.[12],the study conducted both descriptive analyses and quantitative methods to determine the validity of items. The descriptive analysis included item ambiguity, median and percentage agreement. The quantitative method included a content validity index, content validity ratio and content validity coefficient.

Descriptive analysis was conducted first, followed by quantitative analysis. This approach helped to evaluate item properties better. In the descriptive analysis, the median of each item was evaluated first.This was evaluated for the main item and the sub-items.The relevancy of the item was directly proportional to the median value. Consistent with the work of Aravamudhan and Krishnaveni [11], an item with a median of 2.75 or above was fixed for the purpose of the study.

Second, the range of scores for each item or the item's ambiguity score was determined. Since this study used a rating scale of 1 to 4, a range of three or more between scores (or a Rk of four or more) was considered ambiguous in accordance with Rogers’findings [13].None of the 140 items out of 140 was deemed to be unambiguous. Rogers(2010) observed that highly ambiguous items should be avoided.Nonetheless, ambiguous items should not be easily removed until evidence from other methods has been collected. Adequate attention should also be paid when the items are less ambiguous because low ambiguity need not necessarily mean an item is referenced to the domain.It could well be true that an item does not fit well with lower ratings,resulting in low item ambiguity scores.Hence,before any item is deleted on the basis of this score,experts’rating of how well an item fits the category should also be assessed.

Thus, the percentage of experts who felt a particular item was a perfect fit for the category was examined using percentage agreement.At the conclusion of each item,the raters were asked to select“Yes”or“No” in response to the question, “Is this item essential to the domain”. For this purpose, an 80 per cent criterion was used. Out of the 140 items, all items fulfilled the conditions of the percentage agreement. Because of the small number of experts in this study,agreement might readily change, and any choices on the deletion of items should not be made solely on the basis of this figure. After completing all of the descriptive analysis approaches, quantitative analysis was performed.

For each particular item, the content validity index (CVI) is the proportion of experts that assessed the item as 3 or 4(on a scale of 1 to 4, with 4 being an exceptional match). The CVI is represented as a percentage.Wong(2021)[14]200 stated that a CVI value of 1.00 was acceptable for panels of three or four experts, whereas 0.79 or higher was judged acceptable for panels of five or more experts. This proportion was used to account for any chance agreement.The CVI for this study was set at 0.79, or 79%. The 140 items all satisfied the study’s requirements.

Table 2 The distribution of experts

The content validity ratio (CVR) was then calculated. CVR values vary between –1 and +1. Negative numbers imply that less than half of the experts assessed an item as vital. Positive numbers imply that more than half of the experts assessed an item as vital. When half of the experts assessed the item as vital, the number was equal to zero[15]. In order to calculate the CVR, the question “Is the item appropriate or not?” was put into the item content rating review form for the experts who had to answer the question with “Yes” or “No”.The minimum CVR for each item to be considered acceptable was 0.75 for a one-tailed test at the 95% confidence level if a minimum of 8 experts were used for the study[15].In this study,all items had a CVR of 1 as there was 100 per cent agreement on the inclusion of the items.

The content validity coefficient VIk [16] was then investigated. The closer the coefficient was to one,the greater the content validity of the item. The right-tail probability value of validity coefficient V[17] was found in the table for four rating categories. These significant values were V= 0.79. All the items met the standards of content validity under the Content Validity Co-efficient method.

After all the calculations were done, the results for each item under all the methods were summarised. It was decided that the items meeting the criteria of less than four methods (66.67% agreement)should be removed. Finally, all the items met the criteria of four methods fixed for this study.

Findings

The results from the panel of experts yielded the following results.All the 140 items fulfilled the median criteria of 2.75 fixed for the study.With respect to item ambiguity, out of the total 140 items, non were ambiguous. With respect to the percentage agreement, 140 items fulfilled the conditions of the percentage agreement. All the items fulfilled the condition of CVI,140 items fulfilled the conditions of CVR and 140 items met the conditions of content validity coefficient. After all the calculations, the results for each item under all the methods were summarised.

Limitations of the study

One of the major limitations is that the study relied on subjective ratings by the experts and, therefore could be seen as a threat to validity. However, it can also be argued that ratings were proved by experienced experts from the fields that are trained to be objective in their assessments and also, there was a range of experience with the professional experts. Another issue is the difficulty in determining the source of mistakes in the ratings. Because it is impossible to obtain input from experts during a consensus-building meeting, errors may always be speculative. Individual issues such as a lack of motivation/fatigue, a lack of clarity in the rating job, scoring mistakes, and the complexity of administration methods might all contribute to possible errors. Different philosophical views,strict/lenient dispositions, and subjective prejudice are all possible origins. The key to overcoming these constraints is to recruit appropriate and representative experts for rigorous evaluation.

Future directions and conclusions

The development of the instrument followed the steps recommended in the literature for the definition of its content and items. The Working group findings and comprehensive literature search(including the organization’s Model of care) helped in item development. The consensus of expert judgment from a specific number of experts about each item provided agreement on the items and validity of the tool.During the analysis of the findings, no further changes to the instrument were made. At the end of the process the content validity was satisfactory and achieved the parameters recommended in the literature.

This was a quantitative study and did not undertake a qualitative analysis of content validity, including qualitative analysis for content validity enhances the psychometric properties of the tool. The qualitative approach may include focus groups, open-ended feedback and interviews. Therefore, it would be interesting to undertake qualitative analysis to obtain content validity evidence for the Periodic, objective treatment review and nursing evaluation tool.Moreover, content validity only forms one aspect of tool development and is vital to gather other validity evidence ( construct validity and criterion-related validity). Further to validity measure, reliability measures need to be undertaken to standardize the tool.

Nursing Communications2022年13期

Nursing Communications2022年13期

- Nursing Communications的其它文章

- Delphi and Analytic hierarchy process for the construction of a risk assessment index system for post-stroke shoulder-hand syndrome

- A review of obstacles and facilitating factors of implementing Clinical Ladder Programs in nursing

- Spiritual health, empathy ability and their relationships with spiritual care perceptions among nursing students in China:A cross-sectional correlational study

- Qualitative study on influencing factors of refusal of gastric tube placement in stroke patients with dysphagia

- The influence of professional identity and ageism on turnover intention in nursing homes: a cross-sectional study from suzhou, China

- The relationship of family separation and nutrition status among under-five children: a cross-sectional study in Panti Public Health Center, Jember Regency of East Java, Indonesia