Total hip arthroplasty in fused hips with spine stiffness in ankylosing spondylitis

Anil Thomas Oommen, Triplicane Dwarakanathan Hariharan, Viruthipadavil John Chandy, Pradeep Mathew Poonnoose, Arun Shankar A, Roncy Savio Kuruvilla, Jozy Timothy

Anil Thomas Oommen, Triplicane Dwarakanathan Hariharan, Viruthipadavil John Chandy, Pradeep Mathew Poonnoose, Arun Shankar A, Roncy Savio Kuruvilla, Jozy Timothy, Unit 2, Department of Orthopaedics, Christian Medical College Hospital, Vellore 632004, Tamil Nadu, India

Abstract Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is characterized by involvement of the spine and hip joints with progressive stiffness and loss of function. Functional impairment is significant, with spine and hip involvement, and is predominantly seen in the younger age group. Total hip arthroplasty (THA) for fused hips with stiff spines in AS results in considerable improvement of mobility and function. Spine stiffness associated with AS needs evaluation before THA. Preoperative assessment with lateral spine radiographs shows loss of lumbar lordosis. Spinopelvic mobility is reduced with change in sacral slope from sitting to standing less than 10 degrees conforming to the stiff pattern. Care should be taken to reduce acetabular component anteversion at THA in these fused hips, as the posterior pelvic tilt would increase the risk of posterior impingement and anterior dislocation. Fused hips require femoral neck osteotomy, true acetabular floor identification and restoration of the hip center with horizontal and vertical offset to achieve a good functional outcome. Cementless and cemented fixation have shown comparable long-term results with the choice dependent on bone stock at THA. Risks at THA in AS include intraoperative fractures, dislocation, heterotopic ossification, among others. There is significant improvement of functional scores and quality of life following THA in these deserving young individuals with fused hips and spine stiffness.

Key Words: Ankylosing spondylitis; Total hip arthroplasty; Stiff hips; Stiff spine; Spinopelvic mobility; Functional outcome

INTRODUCTION

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) belongs to the spondyloarthropathy group of disorders affecting the young with progressive stiffness of the spine and hip joints. Inflammation of the spine leads to progressive changes with ankylosis and decreased spinal mobility[1,2]. Chronic inflammation in AS of unknown etiology leads to progressive involvement of the spine, hips, knees, shoulders, among other joints[2-5]. Sacroiliac joints are involved in 100% of AS, followed by lumbosacral spine and cervical spine[4,6]. Hip disease is evident in 19%-36% of AS[4], and shoulder involvement is seen in 20% of the disease[7]. Small joints of the hand are rarely involved[6]. Early hip involvement is marked by synovitis with synovial thickening and increased synovial fluid, as evidenced) by magnetic resonance imaging even in asymptomatic hips with AS[8]. Hip involvement with inflammation and edema is accompanied by involvement of the sacroiliac joint, symphysis pubis and shoulders. Subcortical edema in AS is typical with inflammation of the insertion sites of the tendons, ligaments and capsule, referred to as enthesitis[4]. Inflammation with pathological new bone formation is characteristic of AS with hip and spine involvement. The hip joint radiographs reveal concentric osteoproliferation and acetabular erosion[4]. Synovial and capsular inflammation responsible for pain and decreased movement, with other incompletely specified mechanisms, eventually leads to hip degeneration in AS[4,8]. The hip disease progression seems more significant in males with younger age of onset, eventually requiring total hip arthroplasty (THA)[9-12]. Duration of hip disease in AS is reported as 10-20 years, which is less than duration of AS with spine involvement[4,5,13]. Younger age of onset is associated with more hip disease[4]. Disability is predominantly due to decreased mobility resulting in stiffness and activity restriction. Hip disease is seen largely in the younger age group with significant functional impairment[4,14]. Most AS hips have fixed deformities with stiff spines and loss of spinopelvic mobility. THA improves functional outcome in these patients with significant activity limitations and progressive stiffness in their spine and hips.

THA in AS provides significant improvement in the range of movement with marked improvement in function and mobility[15]. However, the associated risks for consideration are heterotopic ossification (HO), reduced range of movement and reankylosis after THA in AS[11].

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The estimated prevalence of Ankylosing Spondylitis (AS) globally is 0.1%-1.4%[16,17] Mean prevalence of 17.6 per 10000 has been reported in Asia[16], with approximately 0.31% (11 to 37.1 per 10,000) reported in China and 7 to 9.8 per 10000 in India[18]. Approximately 25%-50% of patients have hip joint involvement[19], with bilateral hip disease seen in 50%-90% of in AS[12,15,20,21]. Hip involvement in AS varies from 24%-36% according to data reported from Belgium, Spain and South America[4]. Functional impairment predominantly due to hip disease in AS is evident from functional indicator scores such as the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index[1,4]. The Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index and other indicators are used in the assessment of functional impairment due to hip disease in AS[4]. Hip involvement presents with varying degrees of stiffness, with bony ankylosis seen in about 40% at THA[22].

CONSIDERATIONS FOR THA IN AS

Progressive hip stiffness is seen in AS results in loss of function and limitation of activities of daily living. Hip stiffness combined with spine stiffness results in significant reduction of mobility. The progressive disease leads to fixed deformities of the hip. The fused hips at THA have flexion, abduction or extension deformities[11,23,24]. The individuals are unable to sit comfortably due to the absence of a normal spinopelvic mobility pattern that occurs from standing to sitting position.

AS with restricted spine and hip mobility presents with advanced disease for THA due to various social and other reasons. There is a significant reduction in the range of movement in these affected hips with fixed flexion and rotational deformities. AS with fused hips and stiff spines causes significant activity restriction and loss of function. The indication for THA is a significant loss of mobility rather than pain[15].

AS patients for THA need preoperative assessment and anesthetic evaluation for optimal perioperative care[15]. Airway, respiratory and cardiovascular status needs preoperative assessment. The medical management with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, such as anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha agents, must be stopped with rheumatology input and restarted later to minimize risks associated with wound healing reported at 0.9%[15].

Fused hips with AS have a loss of spinopelvic mobility from the stiffness of the spine and this needs to be recognized before THA for adequate preoperative planning. Preoperative templating is essential to plan for correct acetabular component size and restoration of the hip center. THA with cementless fixation would achieve a good outcome[11,23,25,26], however, cemented fixation would be required in hips with capacious femoral (Dorr C) and poor bone stock[15,21,27]. Cementless acetabular components may require additional screw fixation. Cementless fixation preserves bone stock which, would help in future revisions[15]. The bone stock could be compromised due to significant hip and spine stiffness with prolonged restriction of mobility. Comparison for both cemented and cementless fixation at THA have shown good long-term survivorship in AS[17,28].

APPROACHES FOR THA IN AS

THA in stiff hips with AS have fixed deformities[23]. Flexion deformity is the most common[3,10,11], and an extension abduction deformity occurs rarely[24]. External rotation deformities also coexist indicating contracture of the internal rotators and posterior capsule. The surgical approach for THA should ensure the release of the tight capsular tissue and soft tissue to enable full correction at THA. The flexion deformity would require a comprehensive anterior release while the abduction extension deformities would require the release of the lateral structures including the Iliotibial band

The posterior approach has been the most common in AS[11,15]. The lateral approach has also been used for THA in AS and has been advocated for its lower dislocation rates[29,30]. The modified lateral approach would not compromise the abductors further especially in AS, and this would ensure a comprehensive release in these fused hips with flexion deformity[29-32]. Anterior approach has been reported with favorable outcomes in AS with stiff hips[33,34].

The surgical approach chosen should ensure complete release to correct the fixed deformity in these fused hips without compromising the inherently weak abductors[15]. Trochanteric osteotomy aiding exposure has been associated with increased risk of HO. This approach has been gradually abandoned, although it improves exposure[11,15].

FUSED HIPS

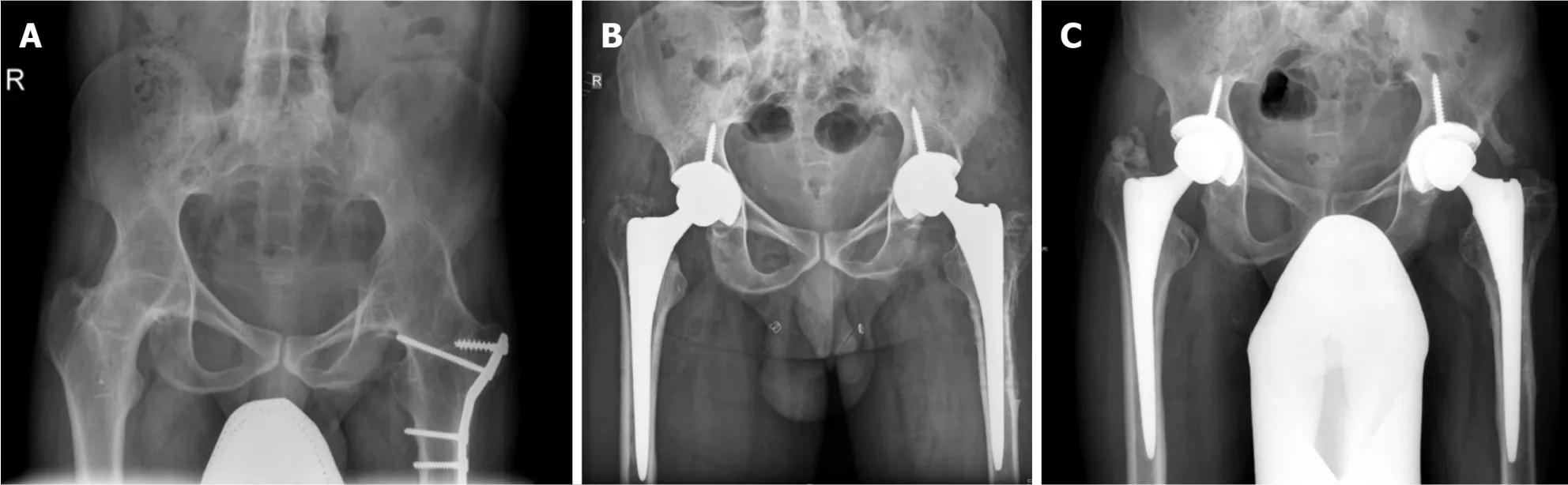

AS with progressive hip stiffness and bilateral hip involvement present as fused hips at THA. Hips with ankylosis requirefemoral neck osteotomy, identification of acetabular margins, reaming into the femoral head and identification of true acetabular floor to achieve correct acetabular component placement (Figures 1 and 2). Femoral neck osteotomy needs to be done with care to prevent damage to the greater trochanter and the posterior acetabular margin[15]. Identification of the true floor is aided by the pulvinar tissue, with care exercised not to medialize the acetabulum[23]. Hip fusion could present with proximal migration of the hip center requiring restoration of the hip center. Subtrochanteric femoral shortening may be required in fused hips with a high hip center[35] (Figures 3 and 4).

SPINE STIFFNESS WITH FUSED HIPS

Spinopelvic movement from standing to sitting is determined by three factors, which include the lumbar spine, spinopelvic mobility and hip flexion[36,37]. Spinopelvic mobility is dependent on sagittal pelvic movement as the anterior pelvic tilt, with lumbar lordosis in the standing position changes to the posterior tilt in the sitting position[38]. Spinopelvic mobility is an essential component in preoperative THA planning, which could lead to early or delayed complications[38-43]. Spinopelvic mobility patterns have also been well described, with recommendations for acetabular component placement at THA[38,39,44]. The preoperative assessment for THA includes a radiological spine assessment, especially with concurrent spinal involvement.

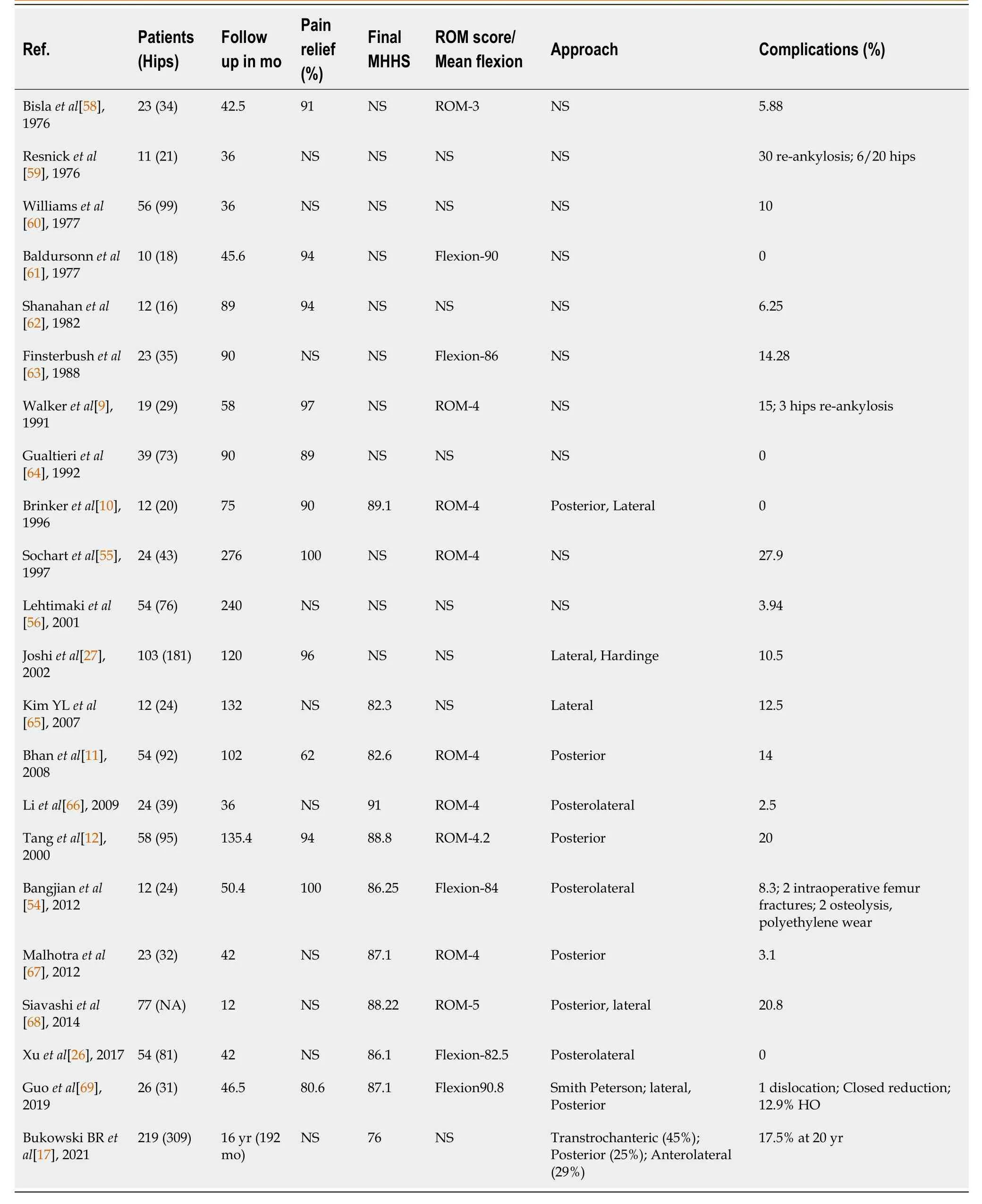

The spine in AS is stiff, and the normal change from sitting to standing is dependent on all three factors that are affected in AS. The change in sacral slope from sitting to standing (< 10 degrees) conforms to the stiff spine pattern[36-38,43]. The stuck sitting pattern with posterior pelvic tilt is common in AS (Figure 5). The stuck standing pattern is not infrequent in AS, as the lumbar spine stiffness may occur with lordosis (Figure 6).

Spine stiffness and altered spinopelvic mobility coexistent with hip disease in AS at THA has been described[41]. Spinopelvic mobility is gradually lost in these young individuals, with the stiffness of both hips and spine causing significant activity restriction. The posterior pelvic tilt with low pelvic incidence had marginal change (< 10 degrees) before and after THA (Figures 5 and 6) conforms to the stiff pattern. The spinopelvic mobility pattern would fall into the rigid unbalanced category[45].

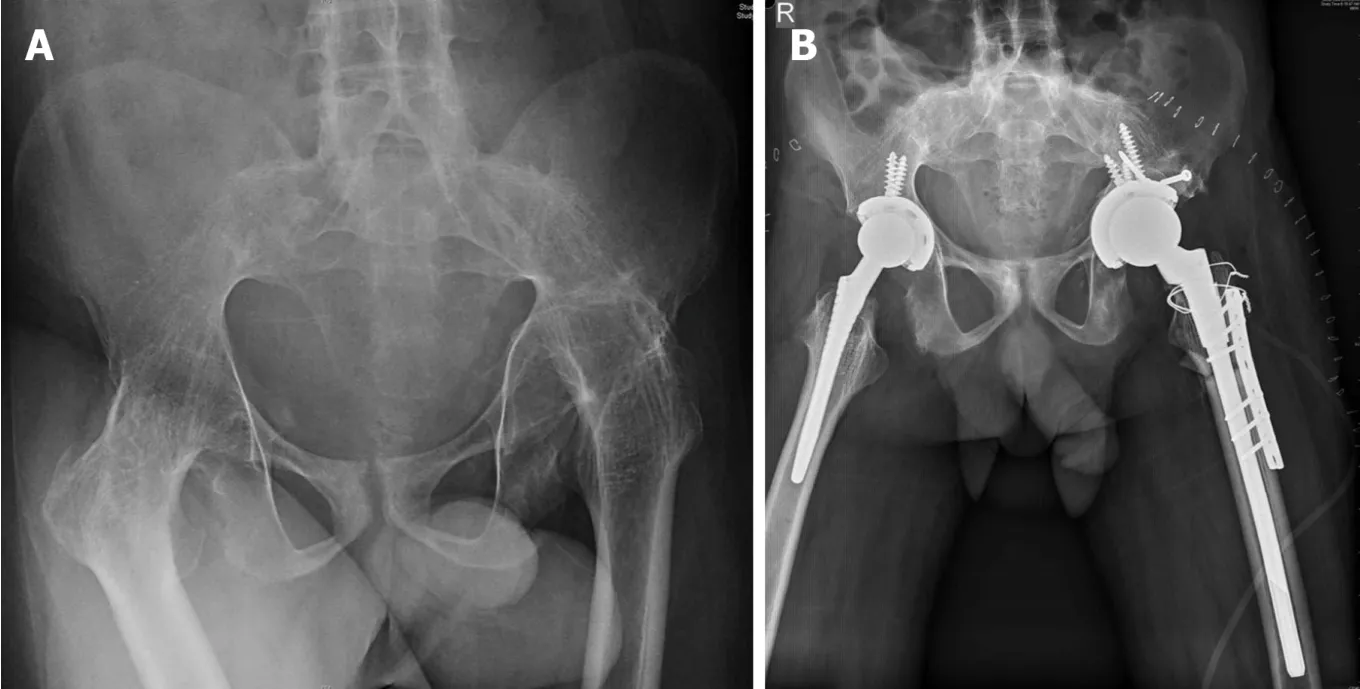

Figure 1 Bilateral fused hips with ankylosing spondylitis in a 43-year-old male at total hip arthroplasty-pre op.

Figure 2 Bilateral fused hips-post op bilateral total hip arthroplasty (Pre op Figure 3) with cementless fixation in 43-year-old male.

The stiff spine requires preoperative assessment to evaluate change with THA[36,37,43,46]. Hu[47] have recommended correction of thoracolumbar kyphosis before THA. However, most AS individuals with stiff hips and spines undergo THA to achieve improvement in mobility and function. The understanding of the normal hip spine relationship and the different patterns brings out the importance of acetabular component anteversion in THA[36,38-40,45]. Progressive loss of spine mobility is common in AS with the loss of normal spinopelvic mobility. Spine stiffness with stiff hips in AS contributes to loss of spinopelvic mobility from sitting to standing. Preoperative assessment includes lateral radiographs of the lumbosacral spine in sitting and standing positions to evaluate the spinopelvic mobility pattern. Preoperative sitting radiographs may not be possible in AS with stiff hips, as these individuals with significant spine stiffness are often unable to sit with the thighs parallel to the floor.

Acetabular anteversion of 15-25 degrees needs to be reduced in these hips with decreased spinopelvic mobility[17,48]. Posterior pelvic tilt with spine stiffness has an associated risk of posterior impingement with subsequent anterior dislocation. Care should be taken to avoid excessive anteversion as this would increase the risk of posterior impingement and anterior dislocation[42,49]. The normal change in inclination and anteversion from sitting to standing is absent[38-40]. Dual mobility hips have been recommended for fused hips associated with a stiff lumbar spine and posterior pelvic tilt to reduce the risk of impingement and dislocation[38,40].

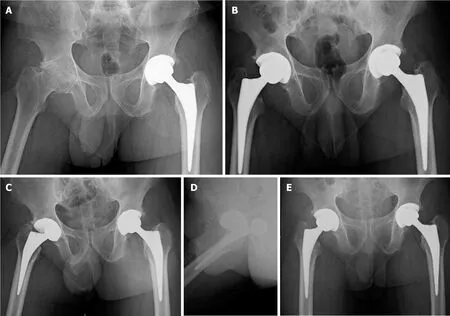

PROTRUSIO

Protrusio in stiff hips is not uncommon in AS. The reason for the medialization of the femoral head beyond the ilioischial line is not fully understood[21,50,51]. Protrusio has been reported in about 17% of hip disease with AS[50]. Preoperative planning includes templating and medial defect bone grafting with reverse reaming for the protrusio with cementless acetabular components. Dislocation of the femoral head during THA in these cases could be challenging, and osteotomy of the neck and head removal may be necessary to avoid intraoperative fractures. The acetabular floor is prepared with caution to prevent medialization, and hip center restoration is essential with autogenous bone grafting and primary cementless acetabular fixation[52] (Figure 7). The protrusio in these hips may present with proximal migration and resorption of the femoral head as well.

Figure 3 Bilateral fused hips and ankylosing spondylitis in a 31-year-old male.

Figure 4 Follow up bilateral fused hips total hip arthroplasty in 31-year-old male with proximal migration left hip (pre op Figure 3).

FUNCTIONAL OUTCOME

THA in AS with stiff hips restores mobility with significant improvement in activity limitation. The mobility is restored with a significant increase in range of movement and good functional outcome[12,21,25,26,33]. Thirty-six item Short Form Survey scores and health-related quality of life are significantly affected in AS[53]. Functional scores have shown significant improvement for bilateral THA with an average change in HSS scores by 60.6 points reported[15]. Harris Hip Score showed improvement from 48 to 73 and 53 to 82 for historical and recent data in the same series[17] (Table 1). The improvement in functional outcome and quality of life have supported the increased incidence of THA in these stiff hips in AS.

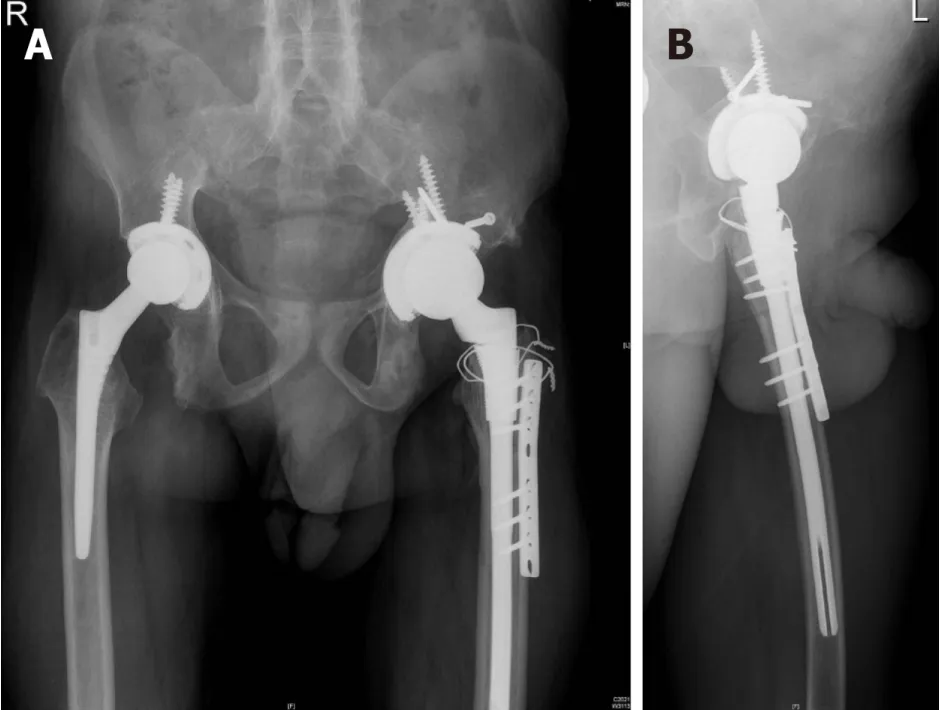

Table 1 Comparison of outcome of total hip arthroplasty in ankylosing spondylitis

COMPLICATIONS

AS with stiff hips could present with poor bone stock due to prolonged immobility and stiffness. Care needs to be exercised during THA to prevent intraoperative fractures reported at 4.3%[11,15,27,54]. Wu[33] reported 1 case of greater trochanter fracture in their series with DAA for THA in AS. Fracture risk is associated with cementless fixation with inadequate bone stock. Fractures have been reported at femoral stem insertion managed with wiring and delayed weight bearing[15]. Bukowski[17] reported 3 proximal femur fractures and 1 acetabular fracture treated with femur wiring and acetabular component retention in their series. Hips for THA with poor bone stock and wide femoral canal (Dorr C) should be planned for cemented fixation. The identification of the medial wall during acetabular preparation and reaming is crucial in achieving the ideal component position at THA in fused hips. Restoration of the hip center with vertical and horizontal offset is essential in achieving THA with a good functional outcome.

Dislocation is a common mode of failure after THA in AS, with earlier reports of 3%-5% at 10 years[11]. Dislocation after THA in AS has been reported at 1.75% managed by closed reduction with successful outcome[15] (Figure 8). Eight dislocations requiring closed reduction were reported in a series of 309 AS hips[17]. Tang[12] reported 2 (2 out of 3) anterior dislocations in their series with posterior approach THA, attributed to hip hyperextension. Dislocation has been reported by Bhan[11] at 4.3% with the posterior approach and Joshi[27] reported a rate of 2.2% with the lateral approach. Wu[33] had reported two dislocations in the posterolateral approach when compared to DAA in their series. Cumulative dislocation requiring open or closed reduction has been reported at 1.9% at 2 years and 10 years and 2.9% at 20 years[17]. Dislocation was predominantly posterior with one out of three hips requiring revision with a constrained liner[17].

Figure 5 Lateral lumbosacral spine radiographs.

Figure 6 Spinopelvic mobility in a 51-year-old male with flexion deformity and inability to sit comfortably prior to total hip arthroplasty, pre op and 29 mo post bilateral total hip arthroplasty ankylosing spondylitis.

Figure 7 Bilateral hip protrusion in 48-year-old male with ankylosing spondylitis and fused sacroiliac joints.

Figure 8 Left total hip arthroplasty with right hip arthritis in a 34-year-old male with ankylosing spondylitis.

The other complications reported included superficial wound infections requiring oral antibiotics in five hips and hematoma formation in five hips in THA for AS[17].

Nerve injuries have been reported with a slightly higher incidence (2.6%) after bilateral THA for AS[15]. Neuropraxia of the femoral, sciatic and peroneal nerves have been reported with recovery rates between 3 wk and 6 mo.

Long-term survivorship following THA in AS has been reported as 92%-100% at 10 years, with rates falling to 66%-81% at 15 years[12,27,55,56]. Aseptic loosening requiring revision in AS has been reported at 9.7%, 14% and 11% at 16-, 9- and 5-year follow-up, respectively[11,17,21]. Cemented fixation in AS had longer survivorship with lower revision rates compared to cementless fixation, which was considered to have better results[17,28].

HETEROTOPIC OSSIFICATION

The incidence of HO in AS after THA has been reported at 11%-13%, with findings of Brooker class 1 in most hips[21,28]. Brooker 3 or 4 (Figure 9), referred to as clinically relevant HO, was seen in 8% of hips[17]. Data in the literature suggest incidence of HO following THA in AS is 9%-77%[9,10]. Re-ankylosis has also been reported with significant HO following THA in AS associated with a reduced range of movement. Trochanteric osteotomy approach has been attributed to increased incidence of HO and re-ankylosis in earlier reports[3,11,57]. HO following THA in AS is probably due to chronic inflammation seen in the joint as well as the surrounding tissues with varying degrees of stiffness. Indomethacin plays an effective role in HO treatment and prevention in these cases[21]. Careful soft tissue handling and copious lavage to ensure removal of excess bone debris before closure after THA play a significant role in HO prevention in these stiff hips.

Figure 9 Bilateral hip ankylosis in a 33-year-old male with ankylosing spondylitis.

CONCLUSION

AS with stiff hips and spine have reduced mobility and function. THA enhances movement and functional activity with significant improvement in outcome. The spinopelvic mobility pattern in AS belongs to the stiff category with minimal change from sitting to standing (< 10 degrees). Preoperative sitting and standing spine lateral radiographs are essential for assessment. THA for fused hips in AS requiresfemoral neck osteotomy, identification of the true acetabular floor and restoration of hip center, vertical and horizontal offset. Cementless and cemented THA have shown good long-term results. Care should be taken to avoid increased anteversion to avoid posterior impingement and anterior dislocation in fused hips with posterior pelvic tilt. Functional outcome significantly improves in these stiff hips. Risks with THA in AS includes intraoperative fractures (4.3%), dislocation (1.9% to 2.9 %), HO (13%), along with other factors including re-ankylosis (6%) and aseptic loosening (14%).

Stiff hips with spine stiffness in AS warrant THA with knowledge of spinopelvic mobility and overall risks to improve long-term functional outcomes.

World Journal of Orthopedics2021年12期

World Journal of Orthopedics2021年12期

- World Journal of Orthopedics的其它文章

- Intraosseous device for arthrodesis in foot and ankle surgery:Review of the literature and biomechanical properties

- Arthroscopic vs open ankle arthrodesis: A prospective case series with seven years follow-up

- Decision aids can decrease decisional conflict in patients with hip or knee osteoarthritis: Randomized controlled trial

- Surgical treatment outcome of painful traumatic neuroma of the infrapatellar branch of the saphenous nerve during total knee arthroplasty

- Rates of readmission and reoperation after operative management of midshaft clavicle fractures in adolescents

- Role of biomechanical assessment in rotator cuff tear repair:Arthroscopic vs mini-open approach